London: dynamic pricing in the international theatre world triggers backlash

Each season London hosts hundreds of premieres — from experimental theatre in intimate venues to blockbuster West End musicals. And while it is still possible to find tickets for £5–15, good seats at popular shows increasingly cost roughly the price of an aircraft wing.

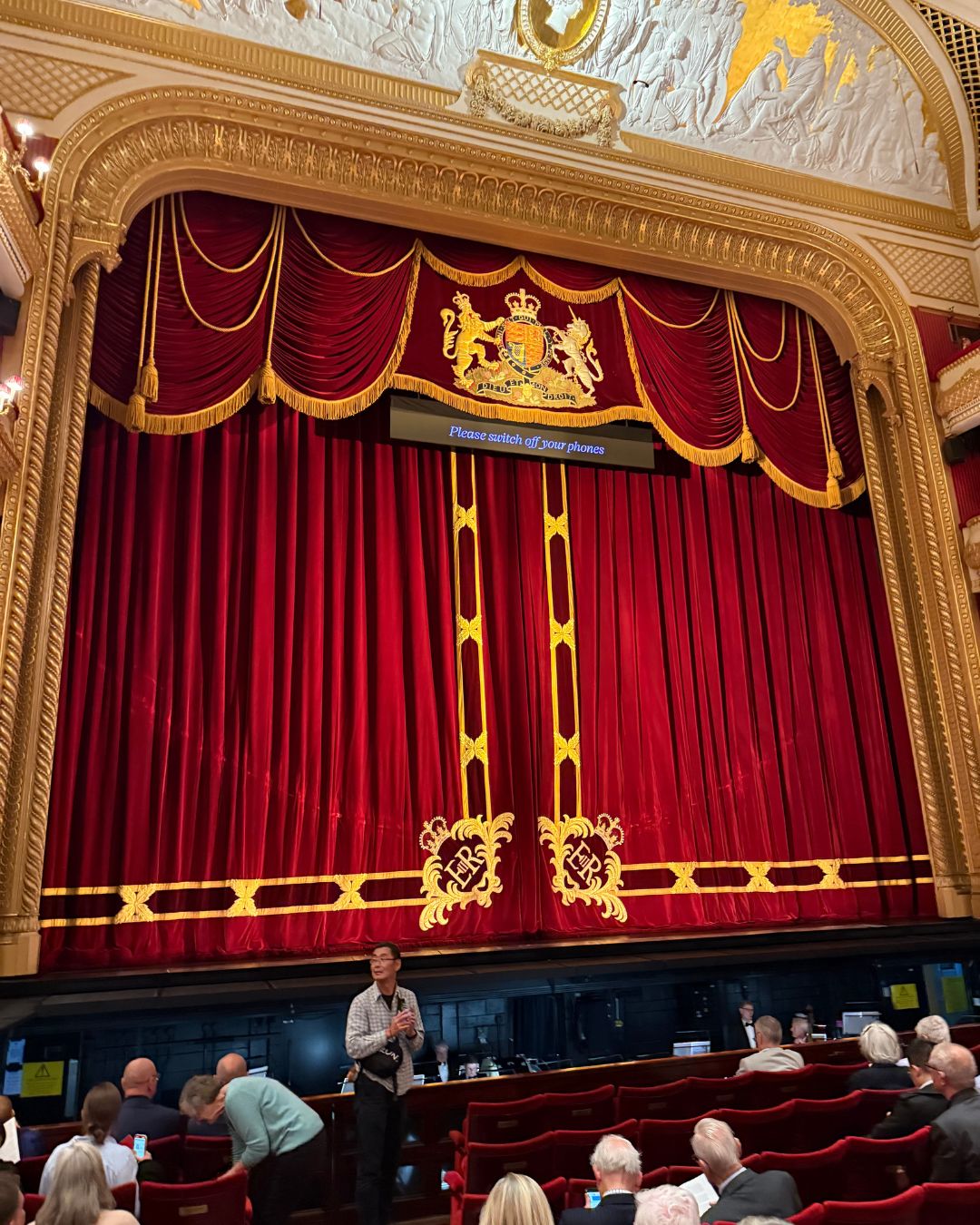

Londoners note with no small amount of frustration that the theatre and live performance industries are undergoing a structural shift. Prices at some theatres now rise during the very process of purchasing, while brokers push concert tickets into five-figure territory — a combination that has fuelled widespread dissatisfaction and even prompted political attention. Under public scrutiny is the Royal Opera House, where the introduction of dynamic pricing for the 2025 season pushed tickets for Wagner’s Siegfried to a record £415. The situation has reignited debate over whether theatre should remain accessible — and how that can be reconciled with new pricing models. Afisha.London examines the issue together with Anastasia Glagoleva of Mountview Academy of Theatre Arts and author of the Telegram channel about theatre productions.

This article is also available in Russian here

How the new system works — and how much Wagner should cost

In September 2025 the theatre introduced a new demand-led pricing model, under which prices fluctuate according to interest. The logic is simple: productions with strong demand become more expensive, while less popular shows stay within reach. ROH argues the change is essential for “supporting financial sustainability”, stressing that the minimum ticket price for Siegfried remains £19, while the eye-watering £415 figure represents the upper tier of premium seats.

Siegfried is the third instalment of Wagner’s monumental Ring Cycle — one of the most demanding operas in the entire repertoire. Almost six hours of music, two intervals (including an extended “dinner break”), large-scale staging and a vast orchestra. The production is directed by Barrie Kosky, with Sir Antonio Pappano, the theatre’s former music director, on the podium. Artistically and technically, it is a challenge for any company.

Read also: The London Christmas Guide 2025: shows, skating and sparkling nights

- Photo: Anastasia Glagoleva

- Photo: Anastasia Glagoleva

How dynamic pricing affects audiences

The ROH controversy has exposed a problem long in the making: the idea of “affordable theatre” in London is increasingly something of a nostalgic notion. Glagoleva points out that audiences today inevitably pay — either with money or with the time and effort spent hunting for the few genuinely accessible options.

She believes the rise of dynamic pricing will push audiences to plan ahead and conduct a little market research:

“A new production is announced — but do we know the cast? How big is the venue? How long will the run be? With some experience and a bit of knowledge, it’s easy to predict which shows require setting an alarm for the ticket release, and which you can turn up for on the day and still find discounted seats because they won’t be sold out.”

Accessibility and quotas for low-priced seats

The Royal Opera House receives more than £22 million in public subsidy each year — a fact that understandably shapes expectations about its pricing policy. Yet Glagoleva notes that theatres do maintain quotas for affordable seats: for young people, local residents, and those receiving Universal Credit. The problem is that these allocations are always small and demand far exceeds supply; such tickets sell out in under an hour.

Recently, the Southbank Centre announced a new programme for young audiences. People aged 18 to 30 can now access dozens of perks — from half-price tickets to the Hayward Gallery to discounts on hundreds of concerts and performances.

Some theatres also offer last-minute discounts on seats that remain unsold a few hours before curtain up. Glagoleva says:

“Advertising these schemes too widely is risky — no one would book in advance; everyone would wait for the last minute. But I do love lotteries, rush tickets and all the same-day discounts. I’d like to see them everywhere, and in larger numbers. But we also understand that if a show like The Seagull with Cate Blanchett sells out in a couple of hours, there’s no incentive to discount — and nothing left to discount anyway.”

Parallels with the music industry — and the government’s response

he situation confronting the ROH is something the music industry has been grappling with for years. Dynamic pricing has long been standard for stadium tours and festivals: prices climb during checkout, and resellers push them into astronomical ranges. The examples are striking: Oasis tickets on StubHub for £3,499; Coldplay for £815; All Points East festival passes reaching £114,666!

The UK government is preparing to cap resales at face value and limit service fees in an attempt to restore control to audiences. But, as Glagoleva warns, heavy-handed price controls in any sector inevitably create black-market incentives:

“I don’t like rising prices in any field, but government price controls lead to black markets and empty shelves — as we know from the history of the USSR.”

Photo: ActionVance / Unsplash

A wider debate about the future of culture

The scandal around the ROH is only one strand of a broader discussion about dynamic pricing and the future of cultural life in Britain. Theatre and music alike are confronting the same question: how to balance financial sustainability with the public’s right to attend the shows they love — without being priced out entirely.

Cover photo: The Royal Opera House, Covent Garden by Peter Evans, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Read also:

Harrods rewrites its own story: the end of the Al-Fayed era

Serge Lifar: reformer of the Paris Opera, the protégé of Sergei Diaghilev, and friend of Coco Chanel

National Gallery vs Tate: a new chapter in Britain’s cultural rivalry. Experts’ view

SUBSCRIBE

Receive our digest once a week with quality Russian events and articles