“Shtandart” in Exile: how the replica of Peter I’s frigate came under threat of deportation from Europe

In the late 1990s, a unique replica of the historic 1703 frigate “Shtandart” was built by enthusiasts with great love and expertise. The ship took part in training voyages across Europe, including in England, and since 2009, it has not entered Russian waters. However, due to recent additions to the sanctions, European ports are now refusing to accept the vessel. Afisha.London magazine explored the history of the original “Shtandart” and its replica and spoke with the captain of the modern frigate, Vladimir Martus, to learn more about life at sea and the fate of this unique historic ship.

A Brief History of the Original «Shtandart»

The first sailing frigate of the Baltic Fleet of the Russian Empire was built by order of Peter I in 1703, with the wooden ship designed by the Dutch-born shipbuilder Vybe Gerens. The frigate was armed with 28 cannons and had a crew of 120 men.

Interestingly, Peter’s shipbuilders drew from the expertise of two naval schools—Dutch and English. According to the captain of the replica «Shtandart», the original 1703 frigate could also be considered a replica, as Peter I modelled it on the English royal yacht Royal Transport, which he received as a gift from William III during his Great Embassy to England in 1698.

Peter’s «Shtandart» participated in the Great Northern War (1700–1721), was used to defend Saint Petersburg from the sea, took part in cruising voyages, and conducted training manoeuvres. However, by 1709, the ship had become unserviceable due to deterioration. After repairs, the frigate remained operational until 1714, but it never sailed again. In 1725, the ship was hauled ashore with the intent to preserve it as a monument, but its deteriorated condition made this impossible, and «Shtandart» was dismantled in 1730.

- Фото: © Shtandart

- Фото: © Shtandart

How the famous replica came to be

The story of the «Shtandart» continued 262 years later, when in 1992, Vladimir Martus, a graduate of the Leningrad Shipbuilding Institute, along with an initiative group, undertook the construction of a historical replica of the frigate. The ship is divided into two zones: historical and modern. Above the gun deck, elements such as the steering wheel, rudder mechanism, masts, capstans, cannons, ladders, and hatches have been preserved. Since then, Martus has served as the ship’s captain.

In 1999, the «Shtandart» was launched at the “Petrovsky Admiralty” shipyard, and in June 2000, it set off on its first voyage, following the route of the Great Embassy—the cities and countries that Peter I visited while learning the art of shipbuilding. The frigate also made an appearance in London: its first visit in 2000 was marked by a ceremonial reception hosted by Prince Andrew. In subsequent years, the «Shtandart» docked at St Katharine Docks, Royal Arsenal Pier in Woolwich, and Hermitage Pier.

Фото: © Shtandart

What makes the replica unique

According to Captain Martus, real wood was used in the construction of the ship, and much of the work was done with hand tools.

“The value of the ship lies in this: during the construction, we were able to recover lost knowledge about the technologies of that time. Now, after the ship has been sailing for 25 years, with the same crew that built it, we study how the ship’s structure is affected by time—by seawater, storms, and different operating conditions. You could say that our team has gained unique global experience: building a ship and observing the evolution of its structure daily for 25 years,” Martus explains.

There are very few authentic historical replicas of sailing ships left in the world, which is why the «Shtandart» Project considers it an important task to preserve the frigate as part of global culture in the fields of shipbuilding and seafaring.

Another unique feature of the «Shtandart» is its international crew, which, until 2022, was made up of roughly half Russians and half people from other countries.

“Our crew is a real ‘melting pot’; for example, when we participated in a festival in Sète, France, in April this year, out of 24 crew members, there were 12 different nationalities, with people from 16 different countries in total. Currently, we have Russians, Spaniards, French, a girl from Finland, and people from Germany and Bulgaria on board. Soon, our Ukrainian and Belgian sailors will be returning. I believe it’s very important not to divide by nationality but to unite. At our level—as ordinary, everyday people—there should be no room for national hatred. Only together can we overcome this incredibly tragic and difficult period in history, turn away from dictatorship, and move toward a brighter future,” Martus believes.

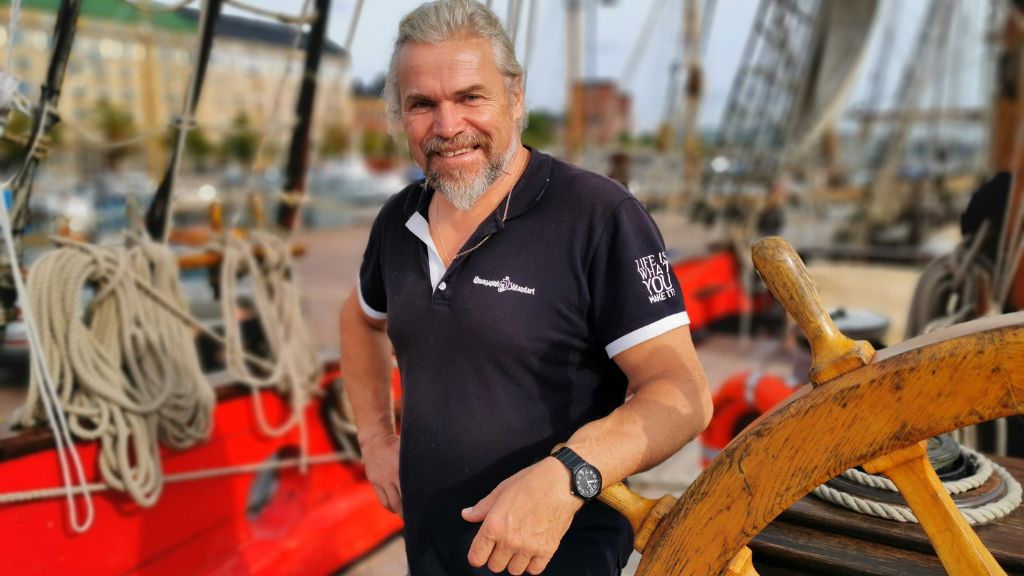

Vladimir Martus

Why the «Shtandart» Hasn’t Sailed in Russian Waters Since 2009

The «Shtandart» has a complex legal history. In 1999, when the frigate first came into existence, it was registered in the Russian State Inspectorate for Small Vessels (GIMS) as a vessel under construction and later as a small vessel. However, in 2007, the «Shtandart» was removed from the registry due to non-compliance with certain specifications. This decision was contested by the shipowner, the «Shtandart Project», in court.

In the same year, the frigate was classified by the Russian River Register as an inland waterway vessel. Based on this classification, the «Shtandart» was re-registered in the state ship registry. In July 2007, the ship obtained clearance for an international voyage using a ship’s certificate issued by GIMS, which had been annulled. This precedent led to the cancellation of the ship’s seaworthiness certificate and a ban on its operation.

In 2008, the «Shtandart» was removed from the state registry, but this decision was declared invalid by the Arbitration Court of St. Petersburg and the Leningrad Region. Although the ship was reinstated in the state registry in April 2009, by June, Russian River Register inspectors had examined the «Shtandart» and found “significant” non-compliance issues that needed to be addressed. However, as the shipowner explained, correcting these issues was impossible due to the ship’s historical design, so the «Shtandart Project» decided to cease operating the vessel in Russian waters. Since then, the frigate has sailed only in European waters.

“We were forced to leave Russia: formally, this was due to pressure from the administration responsible for maritime safety, but there are strong suspicions that behind this were the ambitions of pro-government businessmen to expropriate the ship from its private and overly independent owners—our public and non-profit organisation. The founders of the «Shtandart Project» are the ship’s builders.

As a result, since 2009, the ship has not entered Russian waters but has continued educational and training voyages in Europe. We have wintered in various countries: France, England (Portsmouth), the Netherlands, Germany, Norway, Spain, Italy, Greece, and even Cyprus,” explains Martus.

Фото: © Shtandart

In 2020, the «Shtandart Project» announced on its website that the frigate had successfully obtained full state registration in Russia as a sports training vessel. The crew planned to arrive at a port in St. Petersburg, but these plans were thwarted first by the COVID-19 pandemic and then by the war in Ukraine. The captain notes that the «Shtandart» later voluntarily relinquished its Russian state registration:

“We ourselves refused state registration; we were left with registration under a public organisation (the Sailing Federation). Now we have temporary registration with the Cook Islands, and we are preparing for a survey to obtain permanent registration.”

New сhallenges for the Shtandart

The frigate avoided European sanctions against Russia in 2022 because it was classified as a wooden ship of historical construction. The «Shtandart» continued sailing in European waters, participating in maritime festivals in France and Spain. However, in June 2024, the situation changed when a new entry in the sanctions documents specifically included “replicas of historical ships.”

“While the ship was ‘not under sanctions,’ the French maritime administration ‘strongly recommended’ that we change our registration country, which we did. Since June 6, the «Shtandart» has been sailing under the flag of the Cook Islands, not the Russian flag, and should not have fallen under sanctions. But if the ship was unfortunately registered in Russia as of February 24, 2022, this ‘curse’ cannot be undone. It doesn’t matter whether the shipowner supported the so-called Special Military Operation (SMO) or actively opposed it. We plan to challenge this particular EU decision in court,” Martus concluded.

Фото: © Shtandart

Due to the sanctions, the «Shtandart» has been denied entry to several ports, putting the vessel in a desperate situation: it couldn’t dock, refuel, or replenish food supplies for the crew. Recently, the sailing ship was accepted into the port of La Rochelle, but its future plans remain uncertain.

The «Shtandart Project» acknowledges that its resources are limited, so it plans to take action not only with the help of lawyers but also by garnering public support. A petition has been sent to the European Commission, which can be signed at this link.

Vladimir Martus

Life on Board now

Since the «Shtandart» is now forced to spend 95% of its time at sea due to the inability to dock in European ports, this has taken a toll on the crew.

“The crew has families, and we can only enter port for a day or two once every two to three weeks; the rest of the time we spend either at sea or at anchor. It’s very difficult psychologically to keep the crew stable, to prevent them from losing their minds. Honestly, we’re on the edge,” Martus shares.

Фото: © Shtandart

The frigate is surviving by participating in maritime festivals, film shoots, hosting events and teambuilding games on board. The captain emphasises that it is crucial for the ship to remain independent, which is why they haven’t had sponsors for a long time.

You can support the historic ship, including covering legal expenses for the «Shtandart», through this donation link.

Cover photo: © Shtandart

Read more:

Online education: a path to unlocking student potential beyond traditional schools

How to organize the perfect trip with teenagers and stay sane

Amedeo Modigliani and Anna Akhmatova: the enigmatic nude romance

SUBSCRIBE

Receive our digest once a week with quality Russian events and articles