Somerset Maugham: writer, secret agent in Russia, and favourite of the Soviet intelligentsia

Somerset Maugham – a popular English writer whose books were widely read in the Soviet Union. His captivating and unconventional plots spark the imagination and stir the emotions. Once you’ve read Maugham, it’s impossible to forget him, and film adaptations of his novels, such as The Painted Veil and Theatre, leave a lasting impression. This is largely because the author himself lived a life full of passion and adventure. Afisha.London magazine recounts how Maugham travelled the world, undertook a spy mission in Russia, and lived in a luxurious villa between Nice and Monaco.

This article is also available in Russian here

An Englishman born in France

Somerset Maugham was born on British land, but throughout his life, he considered himself a Parisian, idolising Paris and all things French. As for being English by blood and passport, that was due to the resourcefulness of his parents. Robert Ormond Maugham worked as a lawyer at the British Consulate in Paris, and his wife Edith hosted a literary salon. When they learned that they were expecting their fourth child, they decided to have him born within the consulate walls – to protect their grown son from future service in the French army.

And so, on 25 January 1874, Somerset was born, falling in love with France from an early age. No matter where his travels took him to the farthest corners of the world, he always returned to this country. Maugham’s love for France was tangible and quite substantial – in the second half of his life, he purchased the splendid villa La Mauresque near Nice, where, to the sound of the sea, he wrote his legendary novels.

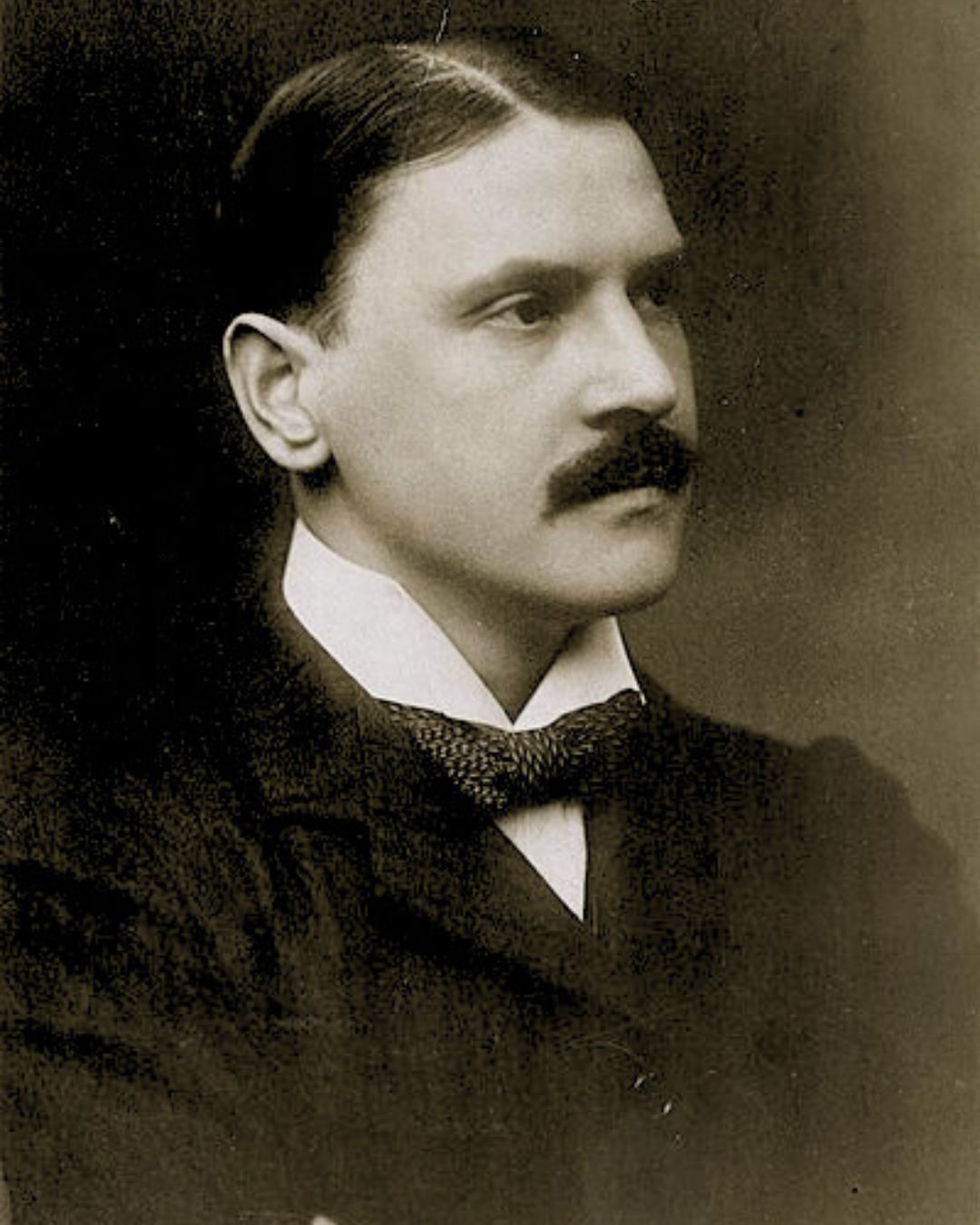

- Somerset Maugham in 1934. Photo: Carl Van Vechten, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

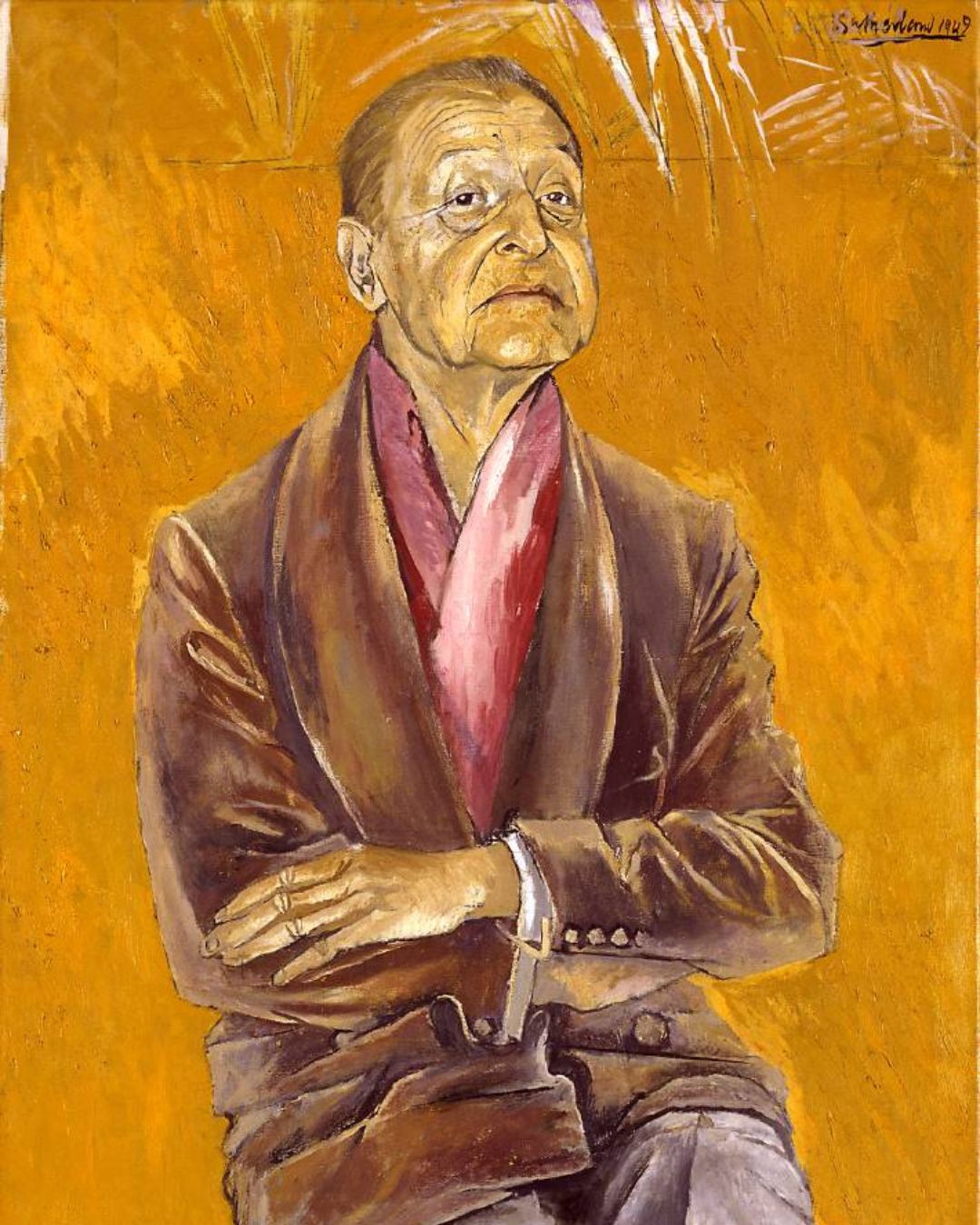

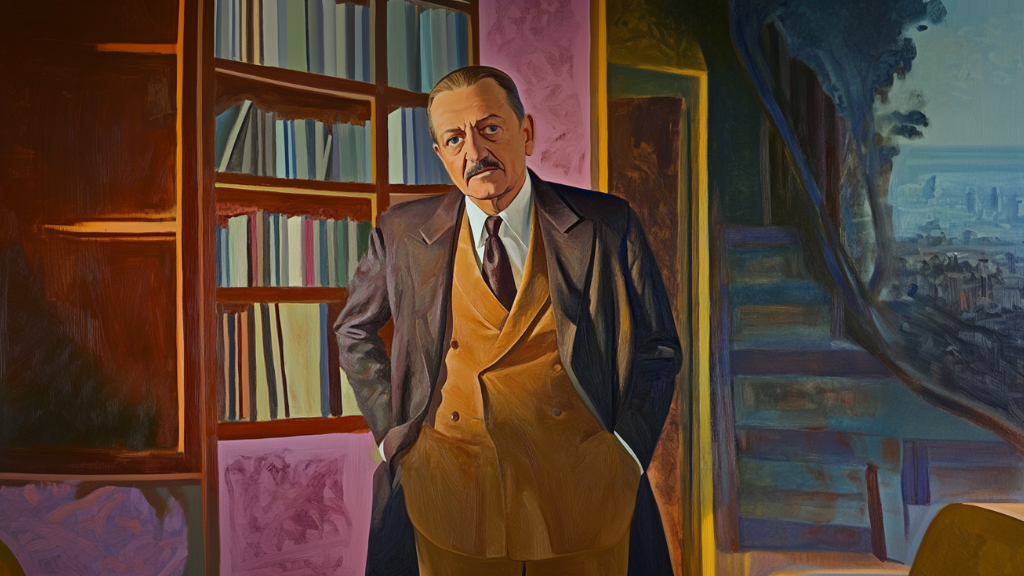

- Writer in a Graham Sutherland’s painting, 1949. Photo: © Tate

However, Somerset’s childhood was far from easy – he was orphaned at an early age. His mother died of tuberculosis, and two years later, his father passed away from stomach cancer. The 10-year-old Somerset was taken in by his uncle, Henry Maugham, who served as a vicar in the English town of Whitstable in Kent. Upon arriving in England, Somerset developed a stammer, which made him a target for bullying and ridicule from his classmates at the King’s School in Canterbury. The future writer was a sensitive child and took the mockery very hard. However, over time, he learned to respond to the taunts with such wit that he perfected his sharp tongue. His academic achievements earned him a place among the top students in the school. Somerset could have aimed for a place at Cambridge or Oxford, but at 15, he left school and went to study literature at Heidelberg University in Germany. Three years later, he returned to England and enrolled in the medical school of St Thomas’ Hospital in London, the oldest in the city.

After his studies, Maugham set off for Spain, and from that point on, travel became a way of life for him. He traversed China, Malaysia, Africa, North America, and even visited islands in the Pacific. Each trip found its way into his writing. Even during his time in Germany, Somerset had begun writing his first short stories, but publishers rejected them. His first taste of success came in London when, in 1907, his adventurous comedy Lady Frederick was staged at the Royal Court Theatre on Sloane Square in the West End. It ran for 422 performances. The following year, the play was performed in New York, and Maugham’s popularity began to grow. However, fate had another challenge in store for him – to take on the role of a British spy and change the course of world history!

How Maugham became a British spy in Russia

After the outbreak of the First World War, Maugham volunteered for the British Red Cross, helping to rescue wounded soldiers from the battlefield. In 1915, MI5, the British intelligence agency, offered him a position as a secret agent in Switzerland. Somerset’s mission was to observe individuals of interest to British intelligence and report back to London. The writer quickly grew bored of the assignment, but it resulted in the creation of a collection of 14 short stories, Ashenden: Or the British Agent, published in 1928.

Read also: Anna Akhmatova in the UK: A Poetess, Muse and Femme Fatale

In 1917, Somerset decided to leave the world of espionage and focus on his personal life. He had just married Syrie Barnardo, a fashionable interior designer, when he was called to MI5’s New York office and presented with an extraordinary offer – to influence the course of world history. Maugham was tasked with travelling to revolutionary Russia, gaining the trust of the Provisional Government, and preventing them from making peace with Germany. MI5 allocated him $150,000 (around $4 million today) to support the head of the Provisional Government, Alexander Kerensky.

- Maugham in 1911. Photo: University of Washington, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

- Syrie Maugham, 1901. Photo: See page for author, CC BY 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Always ready for adventure, the writer accepted. He arrived in the Russian Empire in August 1917, travelling by steamer from Tokyo to Vladivostok under the guise of a British journalist. Maugham spent three months in Petrograd, and everything about the Russian capital amazed him. He wandered along Nevsky Prospect, gazing into the faces of people, seeing in them reflections of characters described in Russian literature – both pale dreamers and stout, coarse merchants. After this trip, he developed a deep interest in Russian classics. In his essays, Maugham often reflected on the works of Leo Tolstoy, Ivan Turgenev, Fyodor Dostoevsky, and felt a kinship with Anton Chekhov, who both fascinated and confounded him. To read these classics in their original form, Somerset even began learning Russian.

However, Maugham never forgot about his secret mission – to establish ties with Kerensky and his inner circle. He was helped by Alexandra Kropotkin, the daughter of the revolutionary and an old acquaintance from London, with whom he once had an affair. Alexandra introduced Somerset to members of the Provisional Government and served as his translator at meetings. Maugham immortalised her in his Ashenden collection, where she became the prototype for the heroine in the story Love and Russian Literature. The character was a caricature but charming. As for Kerensky, Maugham felt only disdain for him, later writing: “I did not sense any charm in him. Nor did he radiate any special intellectual or physical strength.” Instead, Somerset was drawn to another revolutionary – Boris Savinkov, leader of the Socialist Revolutionary Party. In him, Maugham saw the opposite of Kerensky and, as if he were the hero of an unwritten novel, admired his cold-bloodedness and determination.

Photo: Afisha.London / Midjourney

Maugham did indeed manage to quickly ingratiate himself with the most influential people, but he soon felt disillusioned. He was frustrated by the “endless discussions when action was needed,” and perhaps his writer’s intuition was warning him of an imminent change in power. And that’s exactly what happened. Somerset left Russia with a note from Kerensky, which he was supposed to personally deliver to British Prime Minister David Lloyd George. In the note, Kerensky requested weapons and ammunition to repel the Bolsheviks’ attack and continue the war with Germany, but Lloyd George refused. However, by the time Maugham reached London, it no longer mattered – the Provisional Government had fallen, and the Bolsheviks had established Soviet rule. The writer’s grand mission had failed, though Maugham claimed that if he had been sent to Petrograd six months earlier, he could have succeeded.

Maugham’s popularity in the USSR

After the First World War, Maugham published his greatest novels and achieved worldwide fame. However, there were aspects of his personal life that he preferred to keep out of the public eye. For instance, although Somerset was married for 11 years, he favoured men over women. He grew distant from his wife, Syrie, immediately after their wedding and later harboured resentment towards her for the rest of his life, eventually disinheriting their only daughter.

Фото: Afisha.London / Midjourney

His scandalous relationship with his secretary, Gerald Haxton – a young and sociable handsome man who accompanied Somerset on his travels for 30 years – nearly caused Maugham to be ostracised by high society. These personal dramas were known only to the English through local newspapers, while readers in the USSR, where Maugham was beloved and avidly read, remained blissfully unaware. Strangely enough, despite the censorship that prevailed at the time, Maugham’s works were widely published in the Soviet Union. The themes of his novels, which satirised the bourgeoisie and the vices of the capitalist world, fit perfectly with the narrative promoted by Soviet authorities.

In 1956, after Joseph Stalin’s death, the USSR even published Maugham’s Summing Up, where he shared his reflections on his secret mission as a British agent. However, the book was not released to the general public; it was stamped with the label “For scientific libraries” and made available only to a limited circle of readers. Maugham’s popularity reached its peak following the release of an outstanding Soviet film adaptation of Theatre, directed by Jānis Streičs in 1978. Novels such as Theatre, The Moon and Sixpence, and The Painted Veil were staples in nearly every Soviet household library, although the intelligentsia preferred reading his epic on the search for life’s meaning, Of Human Bondage. Incidentally, The Painted Veil was adapted into film three times, with many moved by Maugham’s masterfully depicted colonial setting and the protagonist’s journey from a frivolous, superficial girl to a mature woman.

A well-deserved rest on the French Riviera

In his later years, while resting at his villa in Saint-Jean-Cap-Ferrat on the French Riviera, Somerset Maugham liked to say that his life had been dull and uneventful. This is why he declined offers to have a biography written about him, although in a sense, he wrote it himself – his popular novel Of Human Bondage contains many autobiographical elements. The very villa, La Mauresque, also known as “The Moorish Lady,” was purchased by Maugham in 1928 and became his main residence. “My second child,” Somerset called it. In the 19th century, La Mauresque had belonged to Bishop Félix Charmeton, the personal chaplain of King Leopold II, and in 2005, the Ukrainian oligarch Dmytro Firtash bought the villa for €50 million. Given the cost of neighbouring properties, this was not the highest price. In 2020, another billionaire, Rinat Akhmetov, purchased the historic Villa Les Cèdres, a 1672.2-square-metre mansion with 14 hectares of land on the same resort for €200 million.

Maugham lived at La Mauresque until the end of his days, and it became a mecca for all his friends and acquaintances. Despite this, the writer could often lock himself in his study, which overlooked the Mediterranean Sea, and only occasionally emerge to greet guests, who were attended to by his well-trained staff. Sometimes, he would leave for long journeys, which didn’t deter his guests from continuing to “chill,” as we might say today, at the villa to their heart’s content. It is worth noting that his guests included distinguished figures – Winston Churchill, authors H.G. Wells, Rudyard Kipling, Virginia Woolf, and Ian Fleming, the very creator of the James Bond spy stories, all visited Maugham. Having achieved worldwide fame and earning a good living from his writing, Maugham could do as he pleased and interact only with those, he was fond of.

Read also: Nicholas II and George V: A History of Friendship and Duty

He continued to write passionately until his death on the night of 15 to 16 December 1965, when he passed away from pneumonia at the age of 91 in a hospital in Nice. As Maugham had wished, his ashes were interred at the King’s School in Canterbury, near the Maugham Library, which he donated to the school in 1961, consisting of 500 books.

Somerset Maugham remains in history as a philosopher, a man of the world, and one of the most talented writers of the 20th century. His books have not lost their relevance – with the same wit, ease, and deep understanding of human nature, Maugham continues to offer food for thought on timeless themes.

Irina Lazio/Margarita Bagrova

Cover photo: Afisha.London / Midjourney

Read also:

The biggest museum thefts and art forgeries of 2025

The City’s Symbol Gets a Second Wind: What Awaits the Bank of England by 2029

SUBSCRIBE

Receive our digest once a week with quality Russian events and articles