Joseph Brodsky in London: from Soviet outcast to professor at the West’s top universities

The life of Joseph Brodsky reads like a cascade of fateful, brilliant turns. In his homeland, his unyielding pursuit of creative freedom led him through psychiatric wards and prison cells; in exile, he became a revered professor and found love. On what would have been his birthday, Afisha.London revisits Brodsky’s journey — from persecution to global recognition — a path shaped not only by poetry but also by his essays and verse in the English language.

A rebel and the USSR’s most notorious ‘parasite’

Born on 24 May 1940 in Leningrad, just before the Siege of the city, Brodsky’s childhood unfolded during the harshest years of the Second World War. His father, Alexander, a military photojournalist, was often away; his mother Maria worked as an accountant. Even as a child, Brodsky showed a rebellious streak: he attended four different schools before walking out of the last one mid-lesson, never to return. He left education behind and briefly worked as a lathe operator at a factory, studied to become a submariner, and, aged 16, tried to pursue medicine — helping dissect bodies in a city morgue for a month.

In 1955, the Brodsky family moved into the famous Muruzi House on Liteiny Prospekt — a once-aristocratic building carved into communal flats that had hosted many of Russia’s poets and artists. Brodsky’s family lived in a cramped 40-square-metre space — the now-legendary “room and a half” he would later immortalise in his English-language essay In a Room and a Half, written in New York in 1986. It became a powerful ode to exile, memory, and longing for the homeland he could no longer return to.

Read also: Leo Tolstoy in London: shaping the british literary landscape

Muruzi House. Photo: Фидель22, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

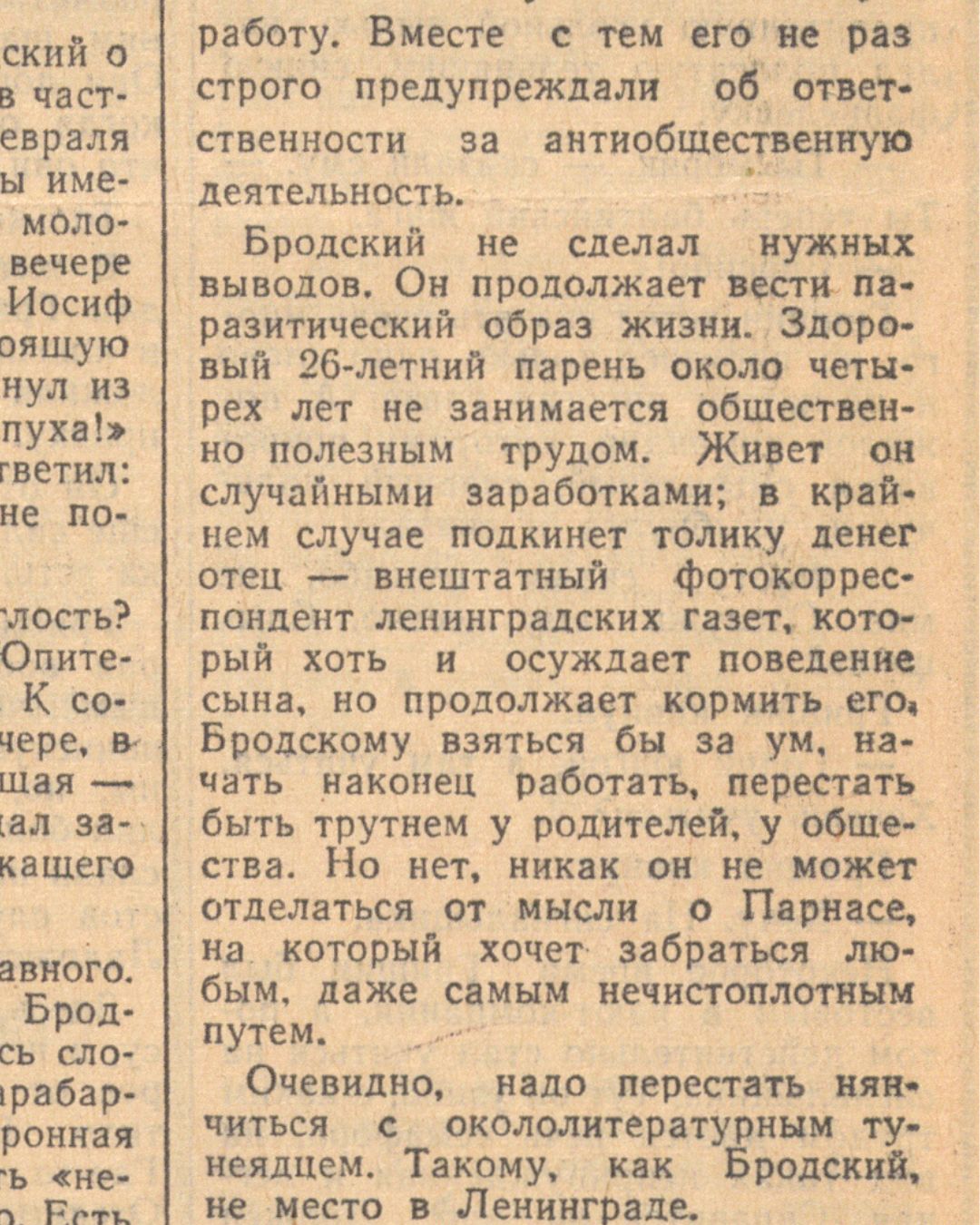

Brodsky lived in Muruzi House for 17 years. In that time, he encountered the city’s intellectual elite, fell in love, and earned the Soviet state’s condemnation as a social “parasite.” For his nonconformist poetry and refusal to conform to ideological expectations, Brodsky was arrested and sent first to a psychiatric facility — where he was declared fit to work but possessing “psychopathic traits” — and then sentenced to five years of hard labour in the Arkhangelsk region. There, in a cold, unheated hut, he immersed himself in English poetry, laying the foundation for his future literary style.

Following pressure from international and domestic voices — including poet Anna Akhmatova — Brodsky was released early. Back in Leningrad, he wrote some of his best work. While his poetry remained underground in the USSR, in the West he was celebrated. American publishers, professors, and readers followed his life closely, published his work, and admired his courage. Invitations to speak at universities and give interviews poured in, much to the irritation of Soviet authorities. Under growing surveillance, Brodsky was summoned in May 1972 and given an ultimatum: emigrate or face more interrogations, psychiatric evaluations, and exile. He chose exile. On 4 June 1972, Brodsky left the Soviet Union for Vienna, carrying with him a typewriter and a volume of poetry by John Donne.

Read also: Anna Akhmatova in the UK: A Poetess, Muse and Femme Fatale

- A fragment of the article about Brodsky in the ‘Vecherniy Leningrad’ newspaper from 29 November 1963. Photo: Kabatov, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

- The suitcase with which Joseph Brodsky left the USSR on 4 June 1972. Photo: Olgvasil at Russian Wikipedia, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

Brodsky’s London: poetry, politics, and a second home

In Vienna, Joseph Brodsky met the Anglo-American poet W. H. Auden — a literary icon of the 1930s and a hero to an entire generation of writers. For Brodsky, Auden became a kind of second Akhmatova — a figure of deep ethical influence and creative mentorship. Together, the two poets travelled to London for the International Poetry Festival. It was Brodsky’s first visit to the city — and one that left a lasting impression.

He was astonished to discover that anyone could walk freely into a session at the House of Commons. Poet Stephen Spender and his wife Natasha brought him to Parliament, and Brodsky was moved by the openness of British institutions — a stark contrast to the world he had just left behind.

Invalid slider ID or alias.

He later dedicated a poem, The Thames at Chelsea, to the British capital. Brodsky had spent years studying English culture and mastering the stylistic tools of British verse, which he then infused into his Russian-language poetry — enriching it with rhythms and references few others could emulate. London became a centre of gravity in his creative life. Throughout the 1970s and early 1980s, he was a regular guest at poetry festivals in Cambridge and beyond.

Read also: Dostoevsky in London and his influence on the British classics

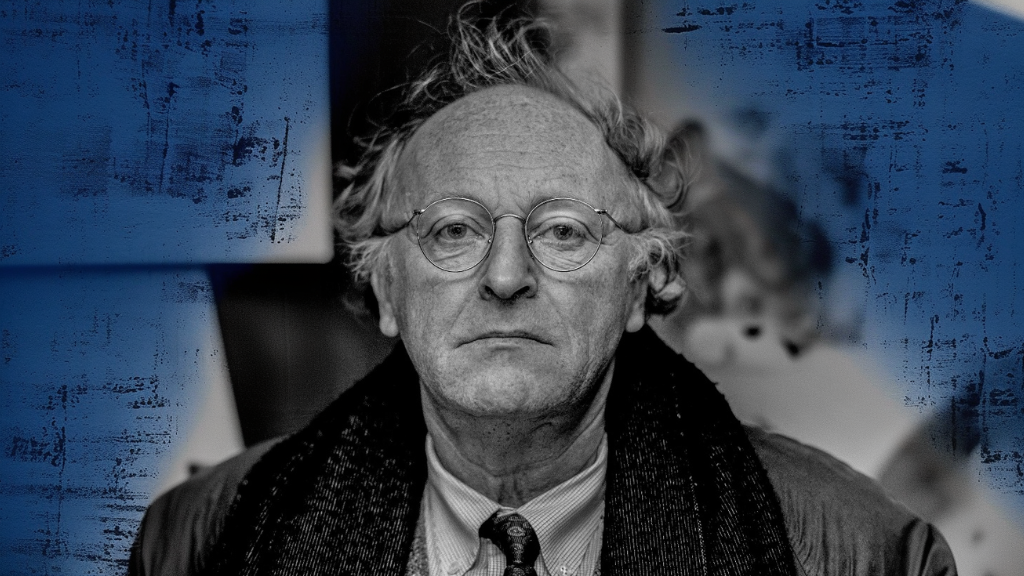

Joseph Brodsky in 1988. Photo: Rob Croes for Anefo, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

Literary scholar and Brodsky biographer Valentina Polukhina recalls a telling anecdote from one such Cambridge event. During a festival dedicated to Russian writer Osip Mandelstam, a group of translators were fiercely debating how best to render the phrase “за дремучую доблесть грядущих веков” into English. Brodsky was summoned for guidance. He strode up and simply said: “Nothing is impossible.” The line earned him more enemies than admirers that day — but it did nothing to slow his growing popularity in England.

In 1978, Cambridge University invited him for a semester-long post as a visiting professor. While in London, Brodsky chose to stay in Hampstead — a quiet, leafy neighbourhood popular with artists and writers. It was here, in 1987, that he received the news of having won the Nobel Prize in Literature.

In 2015, a memorial plaque was unveiled at 20 Hampstead Hill Gardens, a house where Brodsky had often stayed.

Each trip to London brought joy, connection, and creative renewal. In 1985, he appeared in a public dialogue with Stephen Spender at the Institute of Contemporary Arts. In 1991, he was awarded an Honorary Doctorate from the University of Oxford.

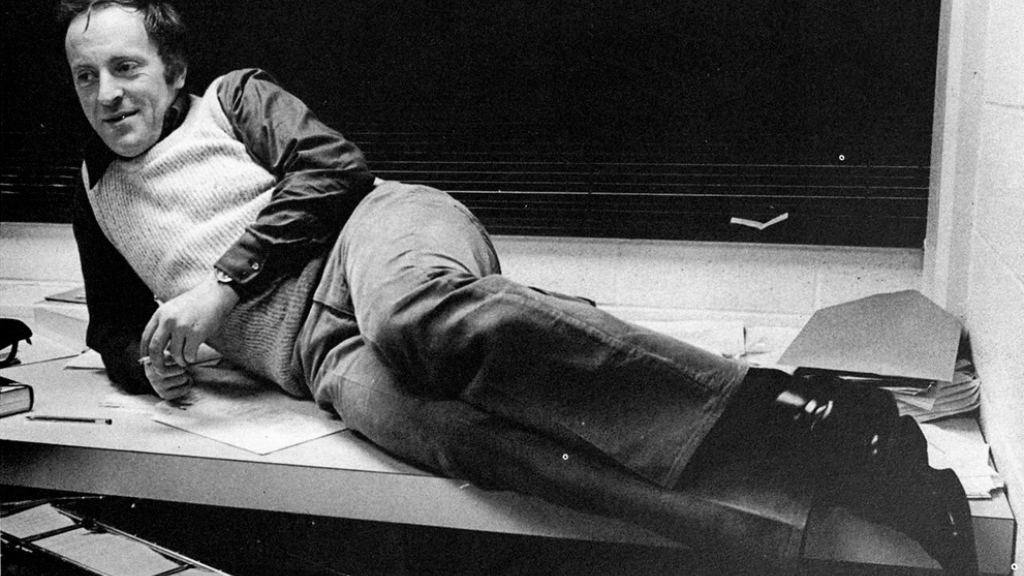

Still, it was in the United States that Brodsky spent most of his exile — and where he found not only fame, but love. Arriving in July 1972, he was swiftly appointed “Poet-in-Residence” at the University of Michigan. Students remembered him vividly: the intense Russian professor with a cigarette always in hand — even mid-lecture.

For the next 24 years, Brodsky would teach Russian literature at six universities across the US and UK, and travel the world reading his poetry — from Canada to Sweden, Italy to Ireland, France to England.

Read also: Ivan Turgenev’s Sojourn in London: a literary ambassador between the Russian Empire and the West

Brodsky in 1973, while teaching at the University of Michigan. Photo: Unidentified (Michiganensian is the University of Michigan yearbook published by University of Michigan), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Fierce love and a quiet harbour

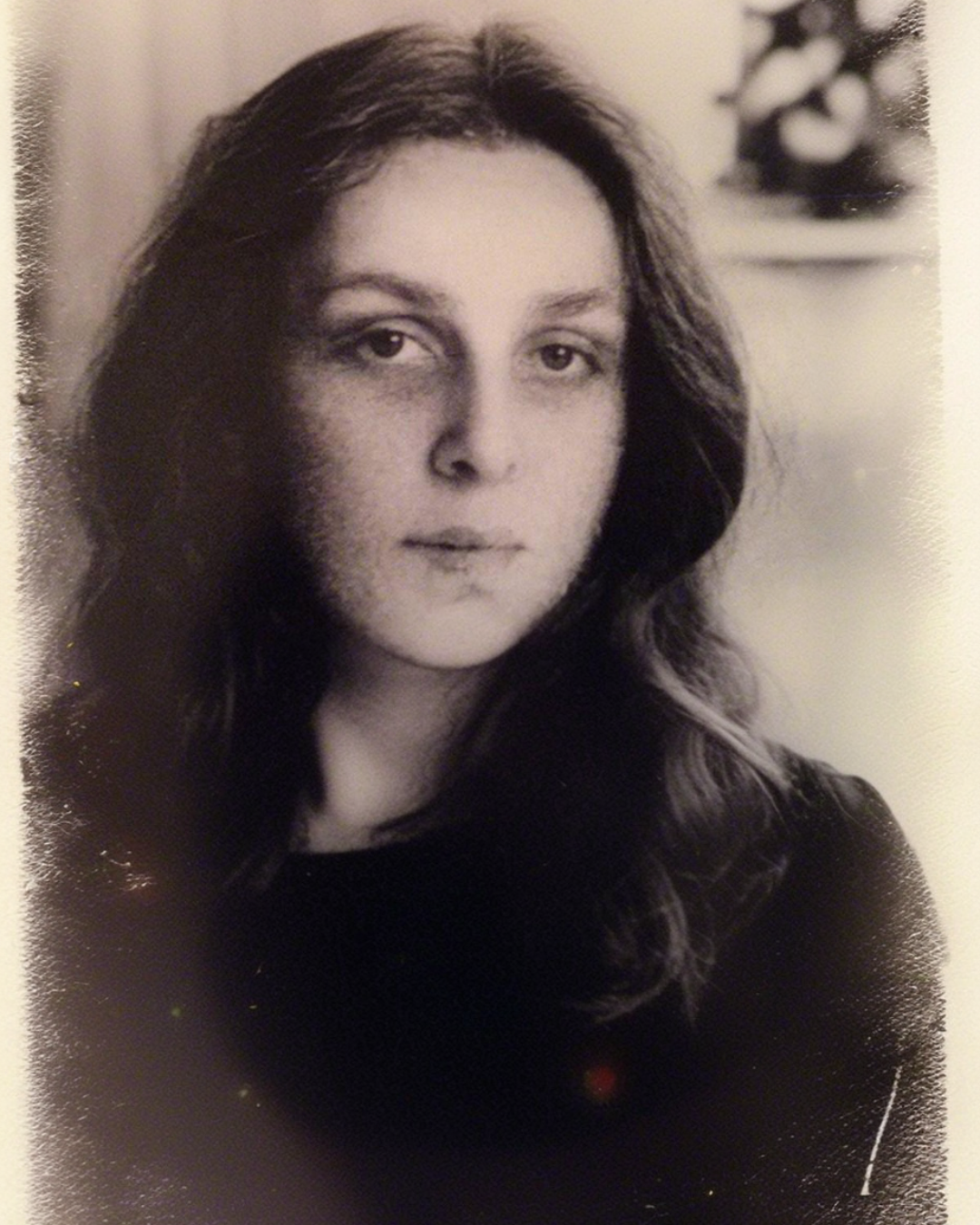

It’s hard to imagine Joseph Brodsky’s lyrical world without the presence of a woman at its heart. For many years, his one and only muse was Marina Basmanova — a painter from Leningrad, mysterious and sharp-edged, known to poetry lovers by her initials “M.B.” scattered throughout his verse.

They met in 1962 at a party in composer Boris Tishchenko’s apartment. Brodsky fell hard. He dedicated countless poems to her and asked her to marry him. She refused. The green-eyed artist inspired some of his most moving poetry — and some of his deepest suffering. In 1964, while hiding in Moscow to avoid arrest, Brodsky learned that Marina had betrayed him with his friend and fellow poet Dmitry Bobyshev. He rushed back to Leningrad, broke off the friendship, and was soon arrested for “parasitism” and exiled to the Arkhangelsk region.

Read also: Lydia Delectorskaya: the Russian émigrée who transformed Henri Matisse’s life

- Marina Basmanova. Photo: reconstruction with Midjourney

- Young Brodsky. Photo: reconstruction with Midjourney

Yet he forgave her. Marina visited him in exile and even stayed for a while — only to return again to Bobyshev. In 1968, she gave birth to Brodsky’s son, but still refused to marry him. The tragic love triangle ended only when Brodsky left the country in 1972. He never saw Marina again, though they continued to exchange letters for years, and her presence lingered in his poetry until at least 1989.

The turning point came in 1990, during a lecture at the Sorbonne. Among the hundreds of students who came to hear the Nobel laureate was Maria Sozzani — an Italian woman with Russian roots. She was captivated by Brodsky’s intensity and intellect. Thirty years his junior, she later wrote him a letter from Italy. Brodsky, sensing something rare, replied at once.

What followed was a love like none he had known before — effortless, warm, deeply human. In the summer of 1990, they met in Sweden, and on 1 September were married in Stockholm City Hall. For the first time, the poet who had always lived on the edge of passion and turmoil found peace. Maria, a thoughtful, well-read woman, was raised on Russian literature by her grandmother, a descendant of a noble émigré family. Friends approved. Sozzani brought calm, domesticity, and an anchor to the poet’s drifting world.

Read also: Serge Lifar: reformer of the Paris Opera, the protégé of Sergei Diaghilev, and friend of Coco Chanel

Maria Sozzani and Joseph Brodsky. Photo: Midjourney reconstruction

In 1993, their daughter Anna was born. Maria made sure she learned Russian — so she could one day read her father’s poems in the original.

But their happiness was short-lived. On 28 January 1996, Brodsky died of heart failure at the age of 55. He was buried on the island cemetery of San Michele in Venice — another city he loved deeply.

Brodsky’s grave. Photo: Modris Putns, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Brodsky never returned to Russia. Even when his parents died, Soviet authorities denied his request to attend the funerals. Only after the USSR’s collapse did his legacy begin to gain the recognition it deserved at home. In 1992, a four-volume edition of his work was published in Russia. In St Petersburg, he was made an Honorary Citizen. Invitations to return followed, but ill health — and a yearning for peace — kept him away.

“The best part of me is already there — my poems,” he once said. And he was right. Through his words, Brodsky gave voice to the exile’s love for a homeland he could not touch — and, in doing so, made Russian poetry beloved by millions around the world.

Irina Lazio/Margarita Bagrova

Cover photo: Sergey bermeniev, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons / Midjourney

Read also:

Pyotr Tchaikovsky in London: a journey of impressions, acclaim, and triumph

The last Stroganov: how Hélène de Ludinghausen revived a lost Russian legacy

SUBSCRIBE

Receive our digest once a week with quality Russian events and articles