Skyscrapers and the City: London’s vertical future balances on historic foundations

London’s relationship with tall buildings has always been uneasy. While the city saw its first major skyscrapers like Tower 42 rise in the 1970s and ’80s, the real shift began in the late 1980s with the transformation of the former Docklands into what would become Canary Wharf. The construction of One Canada Square in 1991 – then the tallest building in the UK – marked the dawn of a new architectural era.

This article is also available in Russian here

Fast forward to today, and two new towers are set to join the capital’s skyline: a residential high-rise in Kensington and a commercial development in the City, built quite literally on Roman ruins. These new projects follow in the footsteps of modern icons like The Gherkin, The Shard, and 22 Bishopsgate. Yet London remains, by and large, a low-rise city – one where every new tower must delicately negotiate the city’s heritage-heavy planning landscape.

In west London, developers SevenCapital and MARK Capital Management are building a £500 million residential development dubbed a “vertical village”. The 29-storey 100 Kensington will feature 462 apartments, nearly 200 of which will be designated as affordable, with an entire block allocated for social housing managed by Notting Hill Genesis. Designed by John McAslan & Partners with interiors by Corstorphine & Wright, the tower will be the tallest in Kensington and Chelsea. Amenities include rooftop gardens, a cinema, a swimming pool, and retail space – an urban microcosm in the sky.

Photo: Seven Capital

But who’s actually buying these apartments? Alisa Zotimova, founder of property agency AZ Real Estate, sees shifting priorities:

“More people are buying to live in, rather than as an investment. Yields on modern high-rises are often modest due to high running costs, especially service charges, which can’t easily be passed on to tenants. Historic buildings tend to offer lower maintenance costs and more character – which is exactly what many are drawn to in London. That said, there’s still value in new-build towers, especially given how rare they are in central areas.”

According to Zotimova, residential skyscrapers remain attractive to overseas buyers from densely populated places like Hong Kong and Singapore, where vertical living is the norm. But for Londoners, tall towers often serve better as statements than homes.

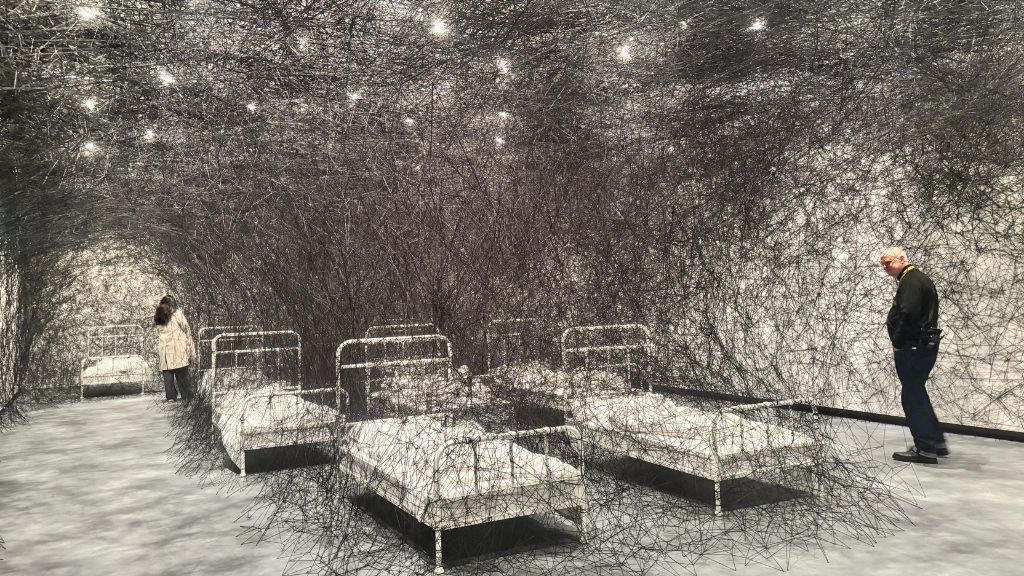

Meanwhile, another skyscraper is about to break ground – this time in the historic core of the City. At 85 Gracechurch Street, developers are planning a modern office tower atop the remains of London’s first Roman basilica. These archaeological ruins will form part of a new immersive exhibition space, echoing the integration of the Temple of Mithras beneath Bloomberg’s headquarters nearby. Due for completion in 2028–29, the Gracechurch development will include public galleries with views over the historic Leadenhall Market, offering a rare convergence of ancient heritage and contemporary commerce.

Read also: Charles Dickens Museum: a journey into the heart of Victorian London

Photo: Woods Bagot

Still, skyscrapers remain a contentious topic – particularly when it comes to residential towers. Architect Artyem Slizunov is among those urging caution:

“Living in a skyscraper is a very particular experience. For most people, it’s tied to a certain life phase that doesn’t always coincide with financial capability. In a city like London, a high-rise may be better suited to lying on its side and forming a low-rise community around a private garden.

- The Gherkin. Photo: Espen Prenzyna / Unsplash

- 432 Park Avenue, New York. Photo: Epistola8, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

As public buildings, though, they have a role – if their design, placement and lifespan are carefully considered. Unfortunately, these structures don’t always age well. The cleaner the form, the better they tend to be received. One of the few examples I’d cite as a successful vertical landmark is 432 Park Avenue in New York.”

London is changing. Whether seen as signs of progress or missteps in urban planning, these new towers are becoming part of the city’s evolving identity. For now, they remain striking exceptions in a city still defined by its historic low-rise skyline.

Cover photo: Alex Tai / Unsplash

Read also:

The largest Henry Moore exhibition in history is coming to London

Great British contemporaries: Lord Norman Foster

25 years of artistic experimentation: Tate Modern marks a landmark anniversary

- The Gherkin. Photo: Espen Prenzyna / Unsplash

- 432 Park Avenue, New York. Photo: Epistola8, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

SUBSCRIBE

Receive our digest once a week with quality Russian events and articles