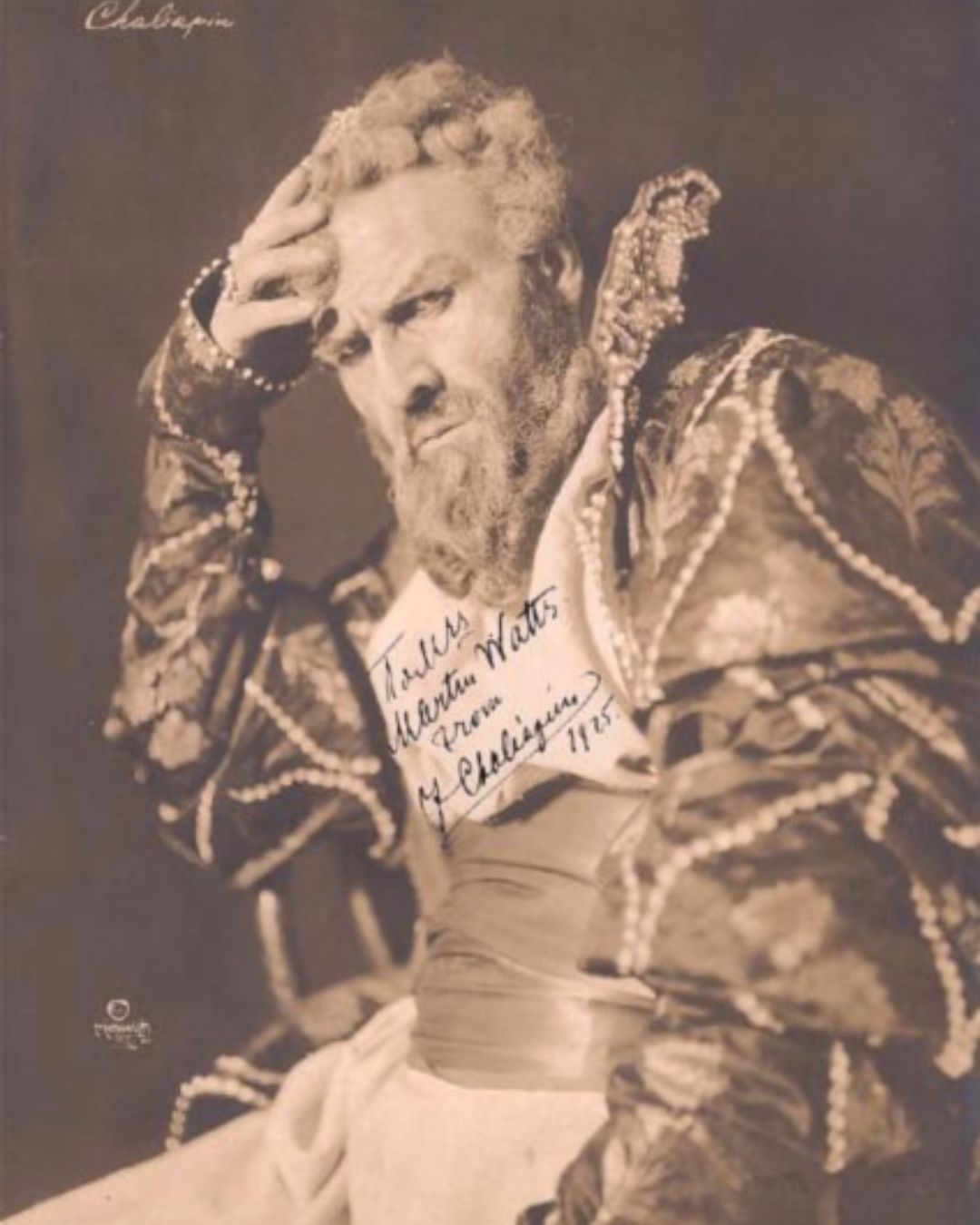

Fyodor Chaliapin in London: the triumph of Boris Godunov and an audience with King George V

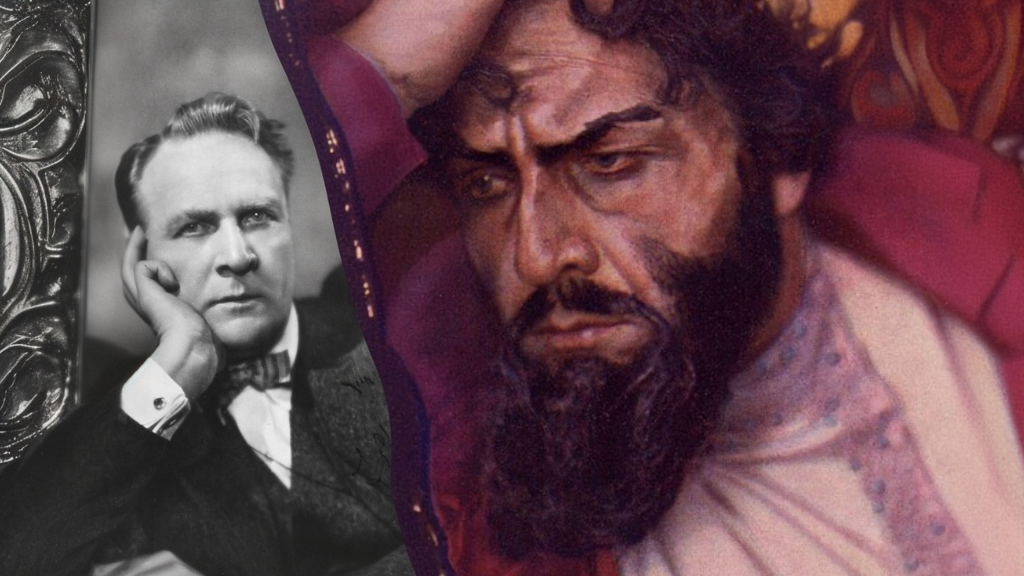

Boris Godunov is a jewel of the Russian stage that required a long and careful cutting before it could truly shine. The opera first caused a sensation in Paris in 1908, and in 1913 it electrified the London stage. A decisive role in its success was played by the performer of the title role, Fyodor Chaliapin. On the eve of Richard Jones’s new London production of Boris Godunov, Afisha.London revisits the history of this legendary opera and traces the key stages in the life of Chaliapin, one of the most virtuoso Russian artists of the 20th century, known to his contemporaries as “His Majesty the Voice”.

This article is also available in Russian here

From peasant roots to aristocratic stature

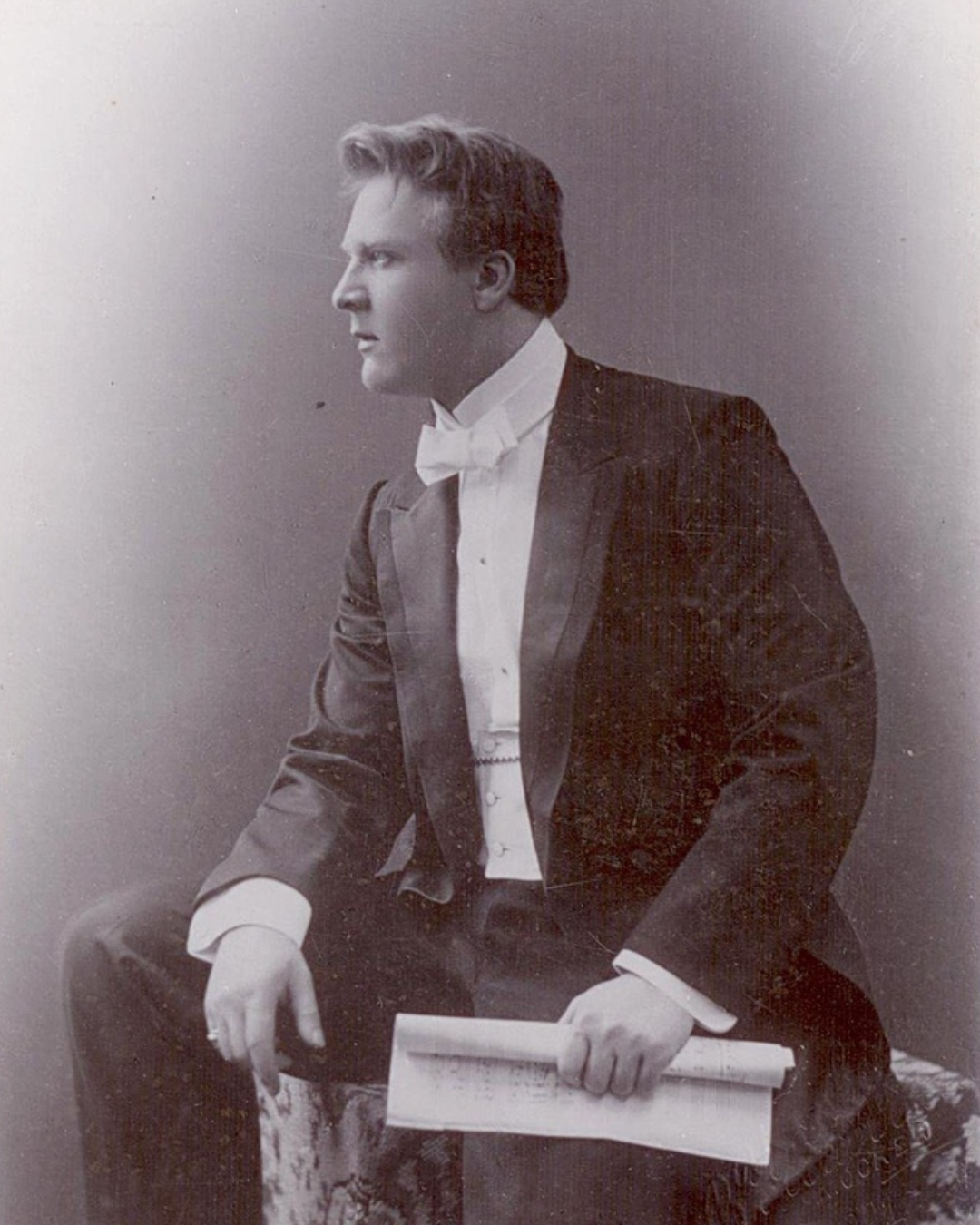

The future legend was born on 13 February 1873 in Kazan, into a peasant family. His father, Ivan Chaliapin, worked as a clerk at the local zemstvo administration. Much of what we know about Fyodor’s childhood comes from his own autobiography, Pages from My Life, published under the editorship of his close friend, the writer Maxim Gorky. Historians, however, suggest that Chaliapin deliberately heightened the drama of these early years, describing beatings by his father and the withholding of money. A hungry and unhappy childhood became part of the self-fashioned image of a natural genius forged through hardship – an image Chaliapin was keen to cultivate. His peasant origins also served him well: in later life he would openly take pride in them.

There is no doubt, however, that the boy was never prepared for a life on stage or a singing career. His parents wanted him to acquire a “proper” trade, while Chaliapin himself was irresistibly drawn to music. At one point he managed to win a harpsichord in a lottery, but his parents locked the instrument away and eventually sold it, despite his desperate pleas to be allowed to play. Soon after, Fyodor asked to join the local choir and, to his delight, was accepted. Singing in the choir became his first source of income and his first encounter with musical literacy.

At the age of twelve, Fyodor set foot in a theatre for the first time. A performance of A Russian Wedding left an indelible impression on him, and the theatre became his overriding passion. From that moment on, he imagined himself on stage, bathed in footlights, spending every kopeck he earned on opera tickets. At fifteen, through personal connections, he was offered his first role in a production staged in the Panaev Garden in Kazan. At the crucial moment, however, he was paralysed by fear and froze on stage. The failure did not deter the future king of the stage: two years later he became a soloist with an operetta troupe from Ufa.

Read also: Emigration of the Romanovs to Great Britain: the story of Grand Duchess Xenia

A natural raconteur and charismatic presence, by the age of twenty Chaliapin had acquired devoted admirers who raised money for him to study in Moscow. Yet fortune truly smiled on him in St Petersburg. In 1895 he received an invitation from Vladimir Telyakovsky, director of the Imperial Theatres, and captivated audiences at the Mariinsky Theatre with his portrayal of Mephistopheles in Faust. In 1901, while touring Italy, he perfected this image of the tempter, transforming it into a symbol of eternal evil and astonishing audiences at La Scala in Milan. Rejecting the traditional red carnival costume, his Mephistopheles appeared in a black toga and the mask of a cold cynic – and was met with rapturous applause.

- Chaliapin as Mephistopheles, photo by Sergei Prokudin-Gorskii. Photo: Sergei Prokudin-Gorskii, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

- Chaliapin in 1901. Photo: Vasily Chekhov, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The Russian and European premiere of Boris Godunov

A fateful encounter in Nizhny Novgorod, at an exhibition of Russian art, brought Fyodor Chaliapin together with the patron Savva Mamontov and the Italian ballerina Iola Tornaghi, with whom he fell passionately in love. Mamontov was prepared to do almost anything to lure the singer away from the Mariinsky Theatre to his Moscow Opera, and to that end he enlisted Tornaghi as an intermediary in the negotiations with Chaliapin. The outcome was decisive: Tornaghi became Chaliapin’s lawful wife, and he himself joined Mamontov’s opera company, where the full breadth of his artistic talent finally unfolded.

Read also: Felix Yusupov and Princess Irina of Russia: love, riches and emigration

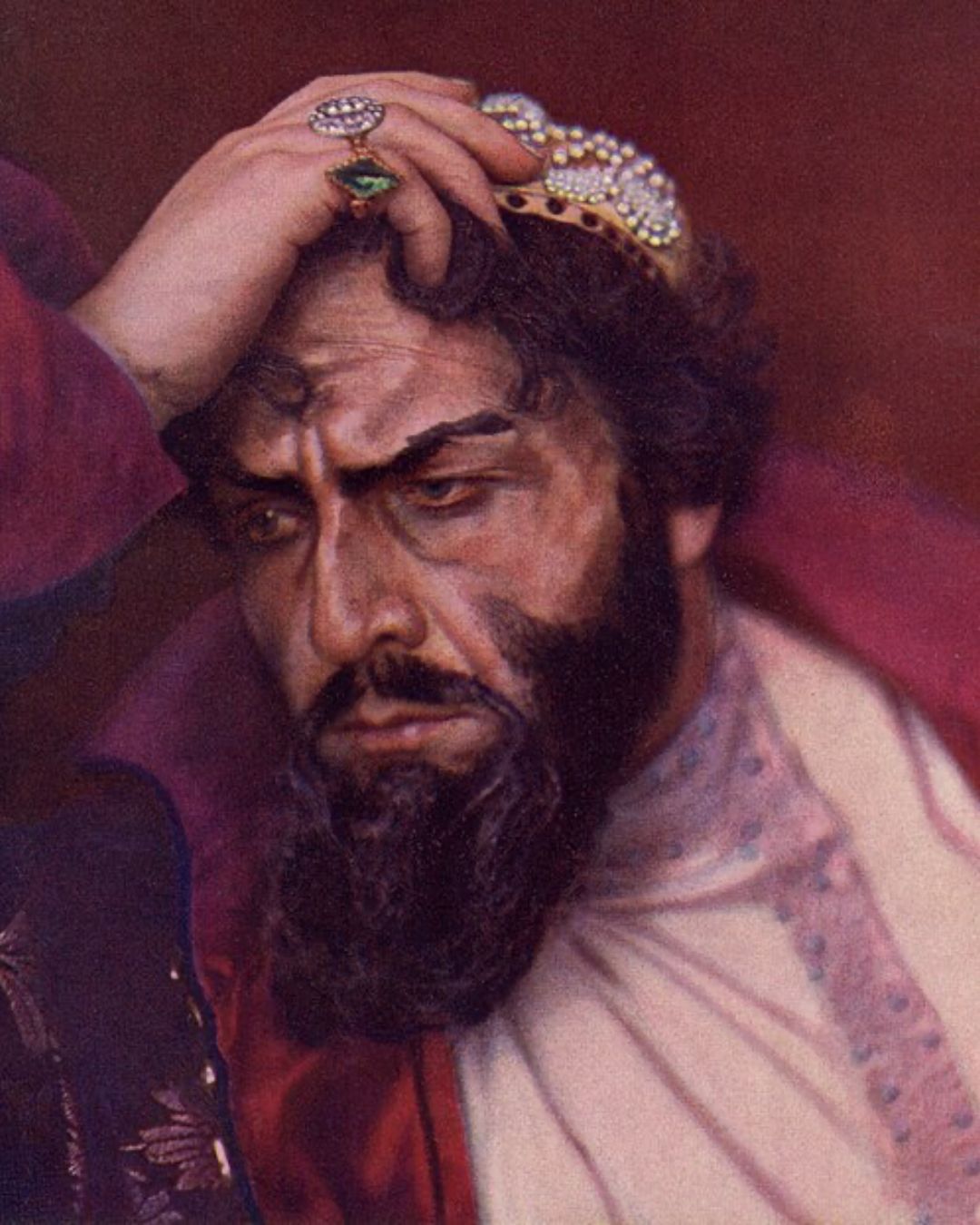

In 1898 Chaliapin sang Boris Godunov in Mussorgsky’s opera of the same name for the first time. The role became his lifelong calling card. He felt a profound kinship with the character, perceiving in Boris both grandeur and suffering. Under his interpretation, the cruel tyrant-tsar was transformed into a tragic figure. Chaliapin later performed the role at the Bolshoi Theatre, La Scala, and the Paris Opera. In 1913 he arrived in London with Boris Godunov as part of Sergei Diaghilev’s Russian Seasons, another pivotal figure in his life and career.

- Chaliapin as Boris Godunov. Photo: Golovin, Alexander Yakovlevich, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

- Fyodor Chaliapin with Iola Tornagi. Late 1890s. Photo: Maksim Petrovich Dmitriev, Public domain, via Wikisource

Through the Russian Seasons, Diaghilev introduced a host of artists to the world, and Chaliapin was among the most significant. After his appearance in 1907 at the Historic Russian Concerts in Paris, alongside Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov and Sergei Rachmaninoff, Chaliapin became the subject of widespread acclaim across Europe. The phenomenal success of these symphonic concerts prompted the impresario to present French audiences with a large-scale Russian opera — Boris Godunov, naturally featuring Chaliapin in the title role.

The premiere took place at the Paris Opera in 1908 and was met with a storm of applause. The opera, devoted to the reign of Tsar Godunov on the eve of the Time of Troubles, appeared in Rimsky-Korsakov’s revision more colourful and less sombre than in Mussorgsky’s original conception. The French press famously declared:

“The Russians took Paris twice: once in March 1814, and again in May 1908, when Chaliapin sang Boris Godunov.”

Diaghilev spared no expense in recreating the splendour of “authentic Russia” on stage. Embroidered sarafans and headdresses, woven with gold thread, were brought from the Vologda province for the production. Chaliapin’s striking tsar’s costume was designed by Alexander Golovin; today, both the costume and its boots are preserved in the collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. Following the triumph of the Russian Seasons, the production was acquired by the Paris Opera. Without Russian performers, however, it failed to replicate its earlier success, and in 1913 it was sold to the Metropolitan Opera in New York, where Boris Godunov was received with enthusiasm.

In Russia, Boris Godunov was first staged in its entirety at the Mariinsky Theatre on 27 January 1874. Initially, the opera failed to win approval, as it diverged sharply from the conventions of the repertoire of the time. For the libretto, Modest Mussorgsky drew on Pushkin’s drama Boris Godunov and Karamzin’s History of the Russian State, completing the work in 1872. The Directorate of the Imperial Theatres, however, long resisted staging the opera.

Where earlier operas emphasised external spectacle and the presence of a prominent female role, Boris Godunov offered audiences a profound psychological drama. The response was deeply divided: conservative circles expressed dissatisfaction, while the press erupted into fierce debate. Critics praised the work for its immersion in the spirit of the people, its evocation of a historical epoch, and its dramatic vitality, while others levelled accusations of weak orchestration and technical shortcomings.

In 1881 the opera was withdrawn by order of the censor and returned to the stage of the Bolshoi Theatre only in 1889. Today, Boris Godunov remains the oldest production in the Bolshoi’s repertoire. In 1911, inspired by the Parisian success, Vladimir Telyakovsky recreated Diaghilev’s production at the Mariinsky Theatre, replicating the same sets and costumes. The French triumph could not be repeated, but what endured were studio photographs and a magnificent portrait of Chaliapin as Boris Godunov, now held in the collection of the State Russian Museum.

The meeting of two monarchs and Boris Godunov in London

In 1913, as part of the Russian Seasons, Sergei Diaghilev and Fyodor Chaliapin brought Boris Godunov to London. Until then, Russian opera had reached London audiences mainly through Italian productions: Eugene Onegin, for example, had been staged in 1906 with Mattia Battistini in the leading role. In June, amid enthusiastic cries of “Bravo!”, Boris Godunov was presented to the London public for the first time.

Read also: Nicholas II and George V: A History of Friendship and Duty

In his book The Life of Chaliapin: Triumph, Viktor Petelin recounts the singer’s memories of how the normally restrained English expressed their admiration with the same exuberance as Italians — a genuine victory for Russian art. King George V was present in the audience and requested a personal meeting with the performer of the title role. Chaliapin went to the royal box exactly as he was — still in make-up and wearing the richly embroidered caftan of the mad tsar. When he entered the box, the King remained silent, and Chaliapin, attempting to fill the awkward pause, spoke first, thereby committing a serious breach of etiquette. George V, however, was so impressed by the performance that he graciously forgave the artist this lapse.

- Chaliapin as Godunov, 1915. Photo: Sergei Prokudin-Gorskii, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

- Chaliapin as Godunov, 1925. Photo: processed by Mariluna, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

London and the Londoners impressed Chaliapin no less than he impressed them. He later recalled visiting the British Museum with Diaghilev’s company, describing it as “a temple where the achievements of world culture are gathered.” From the docks to Westminster Abbey, the city made an overwhelming impression on him with its grandeur and its solid, self-assured presence.

Read also: The last Stroganov: how Hélène de Ludinghausen revived a lost Russian legacy

There were also comic episodes. A darling of the public, Chaliapin loved banter and being at the centre of attention, and to his surprise Londoners turned out to be far less cold and stiff than he had imagined. He spoke with everyone — from society ladies and civil servants to theatre carpenters and craftsmen. The singer was constantly invited to lunches and dinners; the invitations arrived in English, a language he did not know, and he had to ask for the letters to be translated. On one occasion he arrived five days late for a breakfast hosted by the wife of Prime Minister Herbert Asquith, having set aside the envelope and forgotten to have it translated. He was forced to apologise to the lady and restore his good name.

Chaliapin returned to London in the 1920s, shortly after his emigration from Russia. Remarkably, the artist — who had never openly opposed the Soviet authorities — left his homeland for good in 1922. He departed on tour and simply did not return. With him he took his second family, formed with Maria Petzold while he was still married to the Italian Iola Tornaghi. Both women were aware of each other’s existence, and for several years he travelled between the two families, dividing his time between St Petersburg and Moscow.

In emigration, Chaliapin continued his exuberant lifestyle and romantic entanglements. With his new family he settled in a cottage called Rutland Court on Kensington Road, opposite Hyde Park, where he hosted five o’clock tea for friends — fellow singers, artists, writers and aristocratic ladies, including Mrs Asquith and the Duchess of Rutland. In 1931 he was invited by Sir Thomas Beecham to take part in the Russian Season at the Lyceum Theatre — years that coincided with the peak of Chaliapin’s international career.

“The great Chaliapin was a reflection of a fractured Russian reality: a tramp and an aristocrat, a family man and a wanderer, a vagrant and a habitué of restaurants…” — so described the artist his teacher, Dmitry Usatov.

In exile, Fyodor lived with Maria and their children in Paris. He owned a luxurious villa in Saint-Jean-de-Luz overlooking the Bay of Biscay. His final appearance took place at the Monte Carlo Opera in 1937, when he once again sang the role of Boris Godunov. On 12 April 1938 Chaliapin died of leukaemia and was buried in Paris; in 1984 his remains were transferred to the Novodevichy Cemetery in Moscow.

The opera that brought Chaliapin worldwide fame is recognised today as a global masterpiece and remains in the repertoire of leading opera houses and directors. At the same time, the contemporary Boris Godunov at Covent Garden — first staged in 1983 — bears little resemblance to Mussorgsky’s original conception. Each new director continues to uncover fresh facets of this great opera, which remains inextricably linked to the figure of the incomparable Fyodor Chaliapin.

Irina Lazio

Cover photo: Afisha.London (Bibliothèque nationale et universitaire de Strasbourg, France, / Sergei Prokudin-Gorskii, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

Read also:

Ivan Turgenev’s Sojourn in London: a literary ambassador between the Russian Empire and the West

How Diaghilev’s “Saisons Russes” influenced the European art world of the 20th century

Leo Tolstoy in London: shaping the british literary landscape

SUBSCRIBE

Receive our digest once a week with quality Russian events and articles