How Diaghilev’s “Saisons Russes” influenced the European art world of the 20th century

Diaghilev’s Saisons Russes became the most colorful and unforgettable performance for European theatergoers of the early 20th century. The skillful impresario managed to gather amazingly talented artists in his ballet troupe, and Coco Chanel, Pablo Picasso and the best artists of the Silver Age worked on costumes for performances. In honor of the anniversary of the birth of Sergei Diaghilev, Afisha.London magazine tells about the famous entrepreneur and how, thanks to his troupe’s tours, including in the Britain, Russian art was included in the pan-European artistic process. Russian ballet then became the language of cultural dialogue between the West and Russia.

How did Sergei Diaghilev start

The creator of the Saisons Russes was a multifaceted and controversial person, he could charm some people and be inflexible with others, he knew how to open new talents to the world and foresee commercial success. He always appeared in the right place at the right time and was able to use many twists of fate for his own good…but first things first.

Sergei Diaghilev was born on March 31, 1872 into a wealthy noble family in Novgorod province. His childhood was spent in St. Petersburg, and adolescence — in Perm, where the Diaghilevs lived in a mansion that became the center of the city’s cultural life. Musical evenings and performances were held in the house every week — until the family was completely ruined. In 1890, young Sergei returned to St. Petersburg, where the Filosofovs took him under their wing, and entered the law faculty of St. Petersburg University. So, the young man found himself in a circle of like-minded people — his aunt Anna Filosofova was one of the leaders of the women’s movement, and her son Dmitry, Diaghilev’s cousin, would become a well-known literary critic and political observer in the future. Thanks to Dmitry, in his student years, Sergei met Alexander Benois, Lev Bakst and Walter Nouvel — key figures who influenced his development as an artist.

- Sergei Diaghilev, St. Petersburg, 1910. Photo: J. de Streletsky/ St. Petersburg State Museum of Theatre and Music

- Léon Bakst, Sergei Diaghilev with his nanny, 1905. Photo: © The State Russian Museum

After receiving his diploma in the late 1890s, Diaghilev becomes a kind of bridge between cultures — he organizes exhibitions of European artists in St. Petersburg, and shows paintings by Russian masters in Germany, causing growing interest on both sides. It is worth noting here that in those years Western art was poorly represented in Russia, and Diaghilev’s exhibitions brought him both commercial success and the pleasure of introducing foreign culture to the Russian public. On the other hand, Imperial Russia was experiencing a period of flourishing in literature, music, art and theatre, which was called the Silver Age. And the young Diaghilev became his most faithful servant, striving to convey to the Western public the pearls of Russian culture. Even then, he acted in the same way as he later did with the Saisons Russes — he found young talents, looked for wealthy patrons and established connections with the right people. He enlisted the support of Grand Duke Vladimir Alexandrovich, the third son of Alexander II, and then Emperor Nicholas II.

In 1898, Diaghilev founded the editorial office of the Mir Iskusstva (World of Art) magazine, which brought together artists and writers, and the house at 11 Fontanka River Embankment remains his most famous address in St. Petersburg, awarded a memorial plaque. Here the philanthropist lived and worked from 1900 to 1906 until his departure to Europe, where he saw new prospects for the development of his projects. The departure was also facilitated by a piquant turn in Diaghilev’s personal life — he broke off relations with Dmitry Filosofov, who was his first love, and found new inspiration in the person of the dancer Vaslav Nijinsky, the future star of the Saisons Russes.

Sergei Diaghilev (left) and Igor Stravinsky (right), Spain, 1921. © Victoria & Albert Museum, London

“Saisons Russes” in Europe

Diaghilev was going to conquer the European public with the help of his favorite topic — fine art. At the largest international exhibition — the Autumn Salon in Paris in 1906 — he presented icons and canvases of the 18th–19th centuries, as well as paintings by artists from the World of Art group. In 1907, Diaghilev was able to excite the French public with Concerts historiques russes, and in 1908, the Paris Opera premiered the first stage of the Saisons Russes — the richly costumed opera Boris Godunov with Feodor Chaliapin. However, the intuition and entrepreneurial streak told the impresario that something else would lead to real success. At the beginning of the 20th century, there were not so many enchanting shows in Europe, and they mostly staged opera. Cinema was black and white and remained so until the late 1930s, and the bourgeois revolutions meant that the theater world did not yet receive large subsidies, while under Nicholas II in Russia, theaters flourished on large investments from the state. Therefore, sensitive to the mood of the public, Diaghilev established himself in the idea that the time had come to show the world the complex Russian ballet in all its glory. And even more — each performance should carry a piece of the Russian soul with the flavor of oriental sensuality.

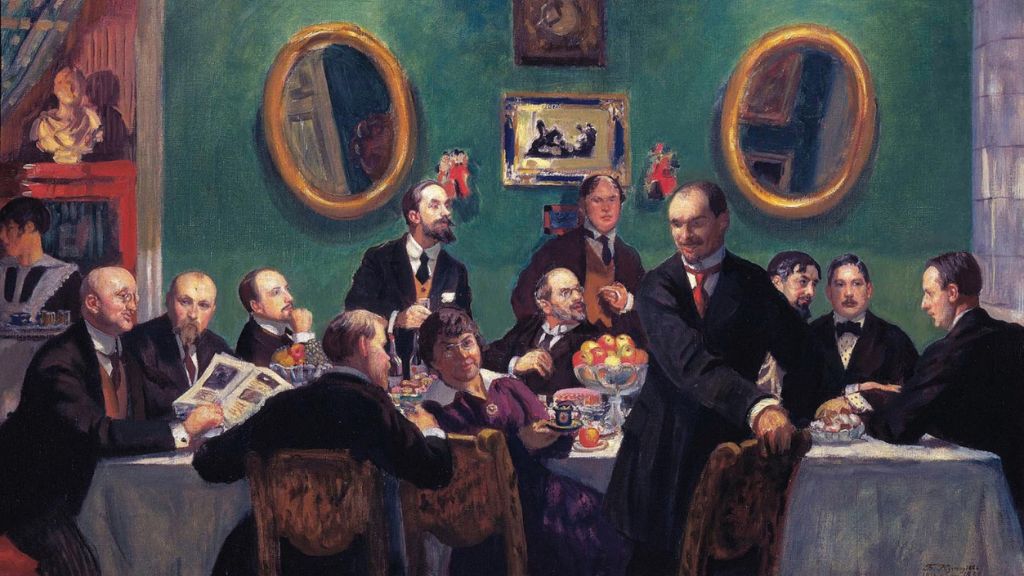

Group portrait of painters of the World of Art, Boris Kustodiev (1910). Photo: © The State Russian Museum

Read more: Ballerina Anna Pavlova: a beautiful swan of two empires

By 1909, Diaghilev had assembled a ballet troupe of talented artists and choreographers from the Imperial Theaters of St. Petersburg and Moscow, many of whom were never destined to return to their homeland. Among them were Anna Pavlova, Tamara Karsavina, Michael Fokine, Vaslav Nijinsky and Ida Rubinstein. Costume designers for the Saisons Russes were Diaghilev’s longtime friends and leading figures of the Silver Age: Lev Bakst, Alexander Benois, Nicholas Roerich, Valentin Serov. Europe was immediately attracted by the unusual concept of the Saisons Russes, which, coupled with the complex staging, luxurious outfits and scenery delivered from the Mariinsky Theater, provided the performances with a resounding success in France. Diaghilev relied on eroticism, oriental bliss and intensity of passions. The hottest ballets in this regard were Cleopatra with Ida Rubinstein and Scheherazade with Anna Pavlova, staged by Fokine in 1909 and 1910. And the oriental motives of the performances and skillfully drawn posters led to a massive passion for the Orient, which was reflected in collections of Paul Poiret, the leading couturier of the 1910s. Harem pants, silk and translucent fabrics, turbans have immodestly entered the Parisian fashion, and even the demand for dark face powder has grown!

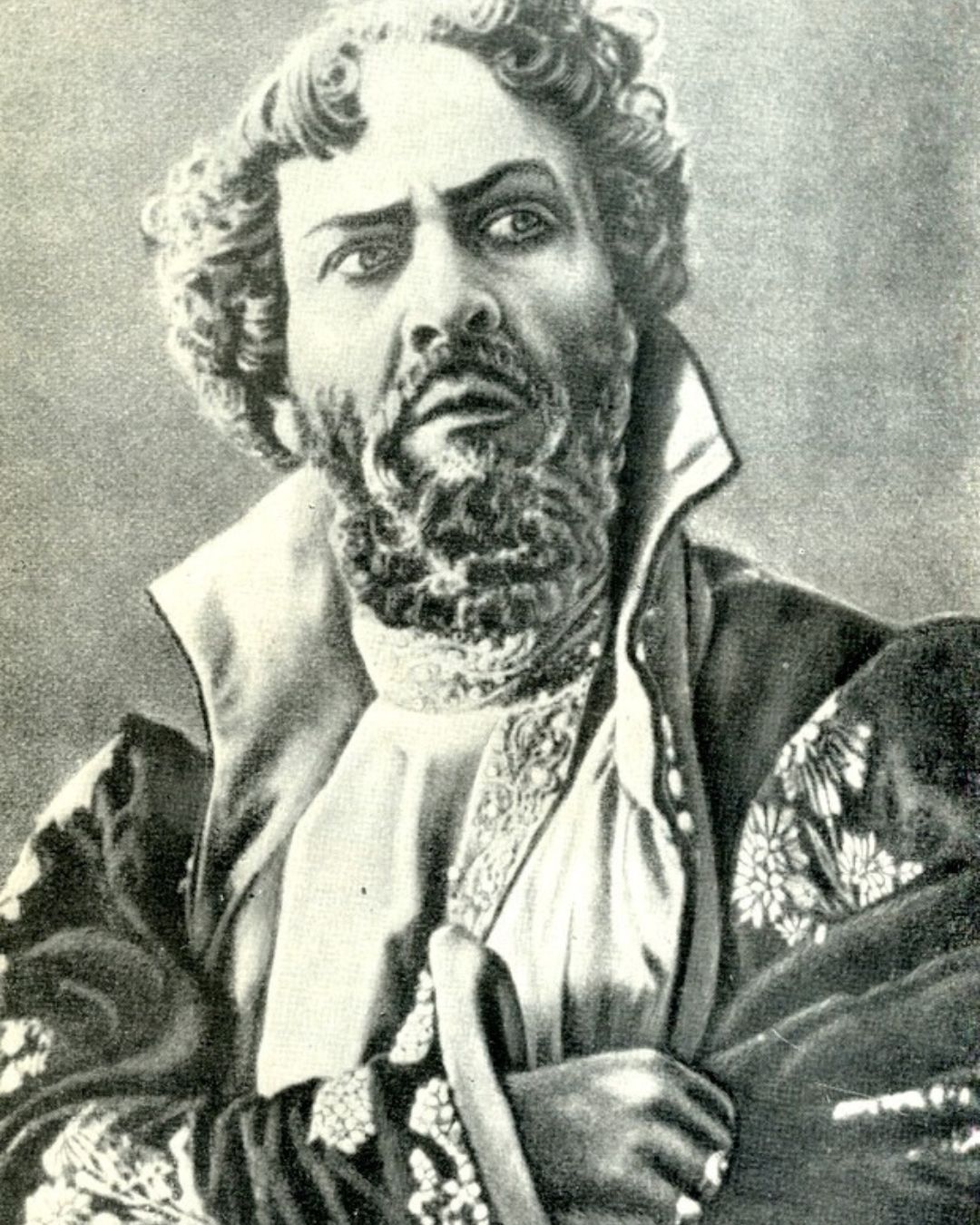

- Chaliapin F. as Boris Godunov (1910). Photo: Lev Leonidov, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

- Ida Rubinstein in ‘Scheharazade’ (1910). Photo: See page for author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Diaghilev in London

In London, the history of the Saisons Russes began in 1911, when resounding success was already established for the entreprise, and it was possible to try your hand at the strict public of London. Doctor of Philology Tatiana Krasavchenko in her article Saisons Russes of Diaghilev in the Great Britain. Paradoxes of Cultural Interaction tells that it was in the Foggy Albion that the Diaghilev’s troupe, to a greater extent than in other countries, met with real recognition. According to Krasavchenko, the artistic and avant-garde temperament of Diaghilev and his troupe somehow complemented the restrained and regimented culture of Britain. The first performance of Saisons Russes in London took place on June 21, 1911 at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden. The Daily Mail wrote about the introduction: “When the orchestra played the prelude in the Le Pavillon d’Armide, the audience looked at each other in surprise. Instead of strumming melodies, usually accepted in the ballet of our country, they heard a wonderful game, restless, passionate, sometimes piercing, capable of being a prelude to a serious opera. This meant that in Russia ballet was a serious art form, and not a frivolous excuse to show pretty girls and outfits”.

Read more: Rudolf Nureyev: an emigrant, who became a ballet legend

In London, performances by the Diaghilev’s troupe were helped to be organised by local patrons, among whom was Gwladys Robinson, Marchioness of Ripon, who patronized people of art. Thanks to Lady Ripon, on June 26, in Covent Garden, in the presence of the king, a gala concert of the Saisons Russes was held, which was included in the list of celebrations dedicated to the coronation of George V. This, of course, meant an unheard-of success. However, in the longer term, the troupe began to be invited to perform every year, and not all performances were favorably received by the public. For example, frank costumes created by Bakst for Scheherazade or frantic, spontaneous Polovtsian Dances often forced the audience, most often the older generation, to leave the hall. The “unaesthetic” ballet The Rite of Spring, staged in 1913 by Nijinsky to the music of Igor Stravinsky, turned out to be a considerable test for the British, but in the end the performance was better received than in Paris, although the impressions from it were of a dual nature.

- Anna Pavlova as Sleeping Beauty, 1916. © Everett Collection / East News

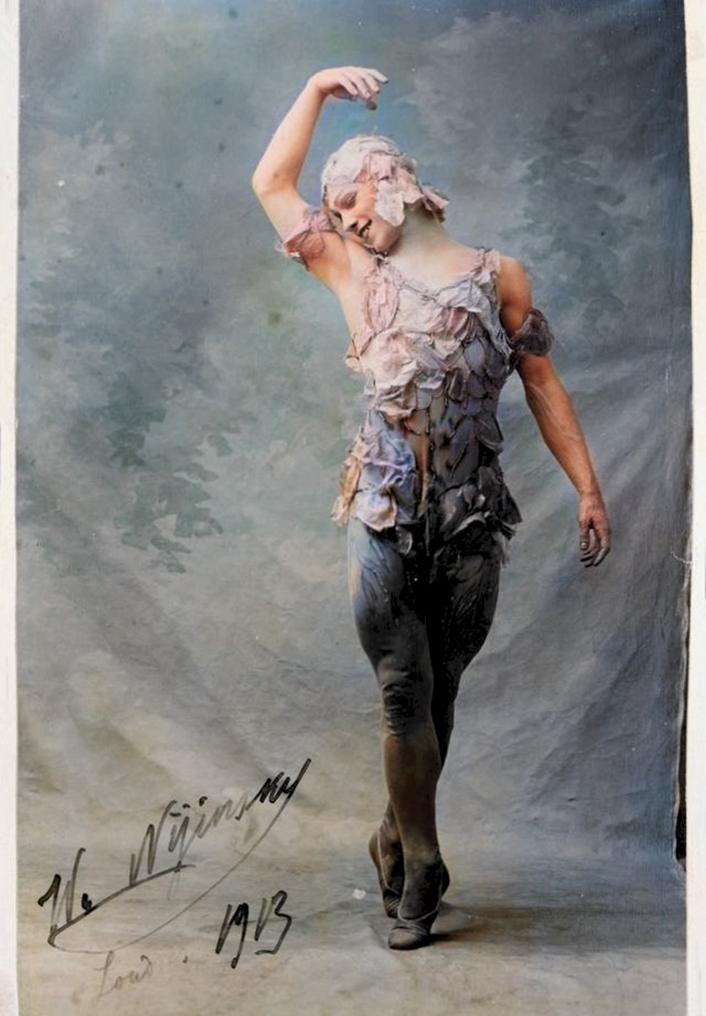

- Signed photograph of Vaslav Nijinsky in the ballet “Le Spectre de la Rose”, by Bert, 1913. Valentine Gross Archive, © Victoria & Albert Museum, London

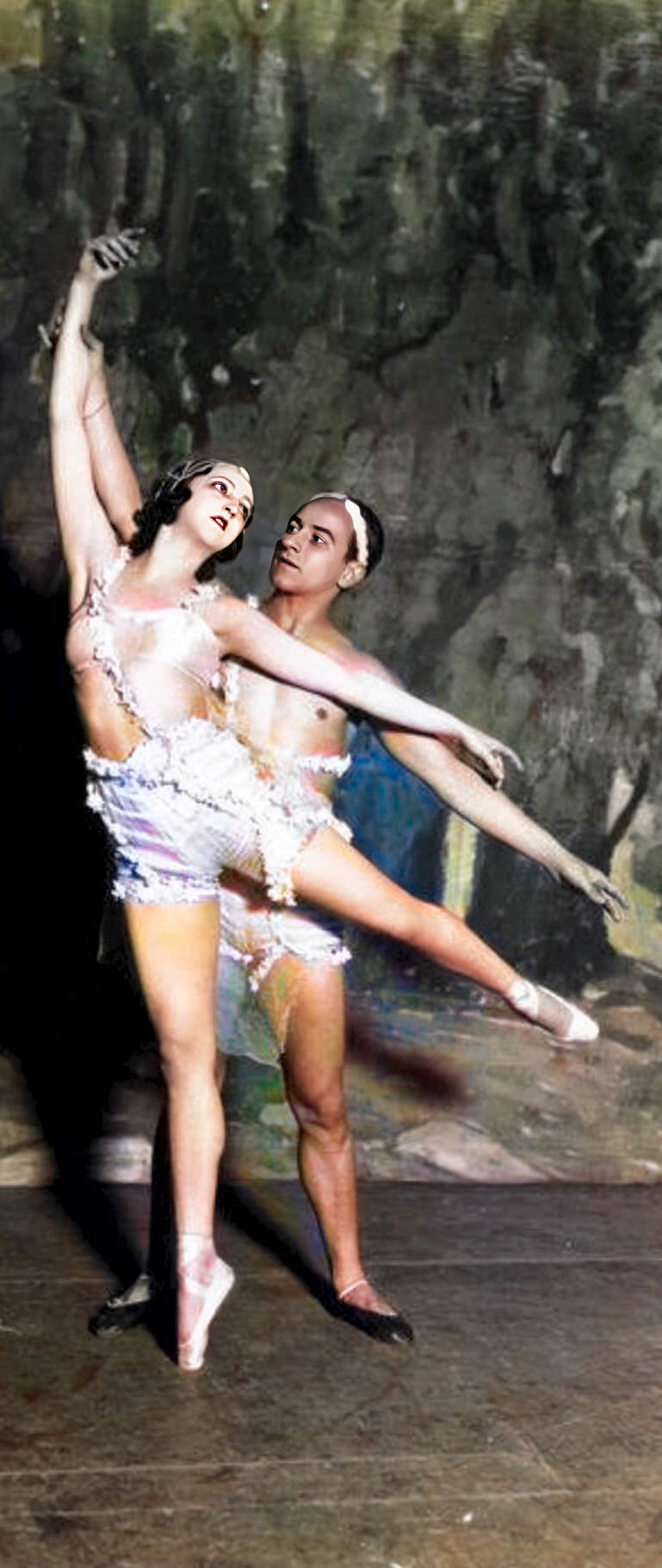

The final performance of Saisons Russes as part of the tour of the artists of the Imperial Theaters was given in the summer of 1914, and then Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes continued to exist, functioning until the death of its creator in 1929. The Diaghilev’s troupe finally got a place in the building of the Opéra de Monte-Carlo and continued to tour around the world despite the fact that the World War I brought a significant confusion to the performances of the artists. In 1918, Diaghilev found himself in a situation where they were not happy to see him in unfriendly France. And then it was London that made the impresario a saving offer in the form of a contract at the Coliseum for the whole season, from September 5, 1918 to March 29, 1919. After that, the ballet troupe again became a frequent visitor to Britain. In gratitude, Diaghilev staged three ballets based on British classics and old engravings: Romeo and Juliet, The Triumph of Neptune and The Gods Go A-Begging. The performances were not a resounding success in the world, but were favorably received by English critics.

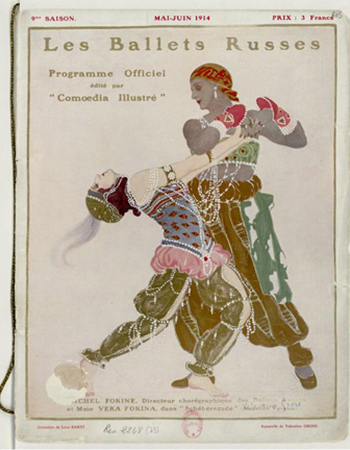

- Posters and programmes of the “Ballets Russes”. Photo: Bakst, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

- Posters and programmes of the “Ballets Russes”. Photo: Valentine Hugo (1887–1968), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Diaghilev’s legacy and support of Coco Chanel

All his life, Diaghilev patronized young talents and suffered madly when they had to be let go, as happened with Nijinsky in 1914, but the impresario himself needed patronage. When he lost the financial support of the imperial court, the French pianist Misia Sert, by the way, a lady with Russian roots, helped him. In 1920, Sert introduced Diaghilev to her friend Gabrielle Chanel, and a charming, friendly and creative tandem was formed. Gabrielle sponsored the performances of the Diaghilev’s troupe, was a ballet costume designer and even allowed the family of the composer Stravinsky to live in her house, which almost caused a spicy scandal. And when Diaghilev fell ill and was dying on the Lido island in Venice, the last days of his life were only shared by Sert with Chanel and his favorite Serge Lifar. The great entrepreneur died on August 19, 1929, his friends Chanel and Sert paid for the funeral at the San Michele Cemetery in Venice. To this day, ballerinas from all over the world bring ballet shoes to the grave of the creator of the Russian Seasons in order to dance successfully.

- Alexandra Danilova and Leon Woizikovsky in “The Gods Go A-Begging”, 1928 © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

- Diaghilev’s gravestone, San Michele Cemetery, April 2011. Photo: Godromil, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

However, with the death of Diaghilev, his brainchild continued to live — members of the ballet troupe dispersed around the world and organized their own productions based on Russian ballet art. It is believed that Diaghilev’s most faithful follower was Serge Lifar, whom the impresario took under his wing at a very young age. After the death of his mentor, Lifar became the premiere of the Paris Opera and directed the ballet troupe, and in 1961 he organized the legendary meeting of the dance genius Maya Plisetskaya with the 80-year-old Chanel, who retained her love for Russian ballet for life.

Irina Latsio

Cover photo: Valentin Serov, Sergei Diaghilev, 1904 / © The State Russian Museum

Read more:

A British Perspective on Russian Classics: James Lance as “Uncle Vanya”

Yehudi Menuhin in London: prodigy, violinist and goodwill ambassador

Exploring Malevich: Locations and Insights into His Revolutionary Art

SUBSCRIBE

Receive our digest once a week with quality Russian events and articles