Rudolf Nureyev: from emigrant to ballet luminary

The name Rudolf Nureyev first reverberated globally in the early 1960s. His groundbreaking dance techniques, mesmeric stage presence, and remarkable emigration story continue to captivate audiences to this day. Often likened to the phenomenon of Beatlemania, Nureyev garnered international acclaim and elevated the art form of ballet, even as he was branded a criminal in his native land. Afisha.London magazine revisits seminal moments in the life of this illustrious choreographer, billionaire, and trailblazing defector from the Soviet Union, for whom London served as a springboard to unparalleled success.

On 17 June 1961, an incident unfolded at Paris’ Le Bourget Airport that would ignite an international furor: Rudolf Nureyev, a young dancer touring with a Soviet ballet company, sought political asylum from the French authorities, asking for protection from KGB operatives. As a result, Nureyev became persona non grata in the USSR, was convicted of treason in absentia, and faced a seven-year prison term along with the confiscation of his property.

Despite these harsh penalties, his audacious move paved the way for an illustrious career. For over 15 years, he graced the stage of London’s Royal Opera House, toured the globe, attained Austrian citizenship, appeared in films, and directed the Paris Opera. “You live while you dance,” Rudolf would often say, affirming that dance was not just his artistic medium, but the very essence of his existence.

Photo: Allan warren, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Born to Stardom: The Formative Years of Rudolf Nureyev

Rudolf Nureyev entered the world under dramatic circumstances on 17 March 1938. According to legend, he was born on a train hurtling along the banks of Lake Baikal as his mother, Farida, journeyed to join her husband Khamet in Vladivostok. Yet some argue that Nureyev might have crafted this captivating origin story to enhance his enigmatic allure. Regardless, his melodious name, bestowed upon him by his Tatar parents, seemed to augur fame.

Shortly after his birth, the Nureyev family relocated to Moscow, only to be swept up in the events of World War II. Khamet enlisted in the army, leaving Farida to seek refuge in her husband’s native Bashkiria along with young Rudolf and his three sisters. In 1943, the family settled in Ufa.

Rudolf’s early years were marked by struggle and hardship. Living in a cramped space with extended family, they subsisted largely on potatoes. Financial constraints were so severe that Rudolf wore his sisters’ hand-me-downs until he started school. These early experiences, replete with frugality and gender-fluid wardrobe choices, may have shaped his later perspectives on sexuality. Rudolf Nureyev became one of the first prominent artists to publicly come out, unabashedly expressing his preference for men and choosing partners with exceptional beauty.

Photo: ETH-Bibliothek Zürich, Bildarchiv / Fotograf: Comet Photo AG (Zürich) / Com L15-0877-0002-0006 / CC BY-SA 4.0, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

In a childhood otherwise mired in hardship, music became young Rudolf’s sanctuary. At the tender age of seven, he began attending folk dance classes where his natural fluidity and dedication did not go unnoticed. However, his world faced upheaval upon the return of his father Khamet from the army. Outraged at what he perceived to be his wife Farida’s excessive indulgence towards their children, Khamet vehemently forbade Rudolf from dancing.

Yet it was an injunction easier set than enforced. The young, spirited Nureyev, already enamoured with dreams of a career in Leningrad, could not be so easily deterred. Fate also smiled on him in the form of his first ballet teacher, Anna Udaltsova. Once a ballerina in Sergei Diaghilev’s esteemed Russian Seasons troupe, she had shared the stage with legends like Anna Pavlova and Tamara Karsavina. Now in exile in Ufa, Udaltsova took Rudolf under her wing. Observing her determined and ebullient pupil, whom she fondly—yet ironically—referred to as the “unwashed Tartar,” Udaltsova was among the first to proclaim, “This is a future genius.”

Read more: Swan Lake: Unusual Interpretations of the Timeless Classic

The White Crow’s Flight to Independence

The tug-of-war between Nureyev and his father, who had envisioned a military career in artillery for his son, ultimately concluded in Rudik’s favour. During his final school years, Nureyev had managed to gain recognition as a theatrical artist. By teaching dance lessons, he earned a considerable income, which ameliorated his parents’ dissatisfaction.

In 1955, his fortunes took a turn for the better. Thanks to a recommendation from accompanist Irina Voronina, Nureyev was accepted into the prestigious Leningrad Choreographic School, now known as the Vaganova Academy of Russian Ballet. However, his headstrong disposition nearly led to his expulsion. Nureyev’s fiery temperament and staunch self-assurance did not sit well with his peers, who deemed him an uncultivated provincial.

Rescue came in the form of his instructor, Aleksandr Pushkin, who not only provided him with a sanctuary but also elevated Nureyev’s unique dancing technique to professional heights. This paved the way for Nureyev’s mentorship under prima ballerina Natalia Dudinskaya and his eventual admission to the Kirov Opera and Ballet Theatre, now known as the Mariinsky Theatre.

Nina Vyroubova, Sergei Golovine, Alicia Markova and Rudolf Nureyev following their performance of “Sleeping Beauty” in Paris (June 23, 1961). Nureyev made his debut with the Marquis de Cuevas Ballet Company. Photo: AP

This tumultuous chapter in Nureyev’s life, fraught with inner conflicts and vacillations, is masterfully portrayed in the British film “The White Crow,” directed by Ralph Fiennes. The film delves deep into the complexities of Rudolf’s persona, exposing his inner uncertainties alongside his overriding passion—his unquenchable thirst for dance.

The film’s climax, which also marks a seminal moment in the artist’s own narrative, revolves around an incident that took place during the Kirov Theatre’s 1961 tour in Paris. In the City of Light, Nureyev found the freedom he had long yearned for. He openly mingled with the local gay community and embarked on romantic liaisons without inhibition. Such behaviour was not merely frowned upon according to Soviet social norms; it was downright impermissible and subject to punishment.

The tour’s final destination was set to be London. As the entire troupe assembled at the Paris airport ready for departure, KGB agents confronted Nureyev, confiscating his tickets. They explained that instead of continuing to London, he was to return to Moscow—supposedly for a meeting with Khrushchev himself. Nureyev was acutely aware that should he go back, he would fall under the suffocating surveillance of Soviet authorities, and the doors to Europe would be irrevocably closed to him.

In this precarious moment, his affluent friend Clara Saint intervened. She managed to persuade the French police to protect Nureyev, setting the stage for his audacious move. Faced with this narrow window of opportunity, Rudolf took the decisive step: he formally requested political asylum, literally leaping out of the encirclement of special agents who had been sent to detain him.

This ‘leap to freedom,’ as it has come to be known, remains an enduring subject of both debate and admiration, constantly being embellished with new details and spun into ever-growing legends.

Watch the film about Fabergé exhibition in London:

The London Chapter: An Unforgettable Partnership with Margot Fonteyn

In the Western world, Rudolf found himself in a precarious position: isolated and a stranger in a foreign land, his friends and family back home were being pressured by authorities who had branded him a traitor. The Soviet Union responded by placing restrictions on artists travelling abroad to prevent any recurrence of the Nureyev incident. Meanwhile, many European theatres hesitated to engage the incendiary dancer, wary of becoming ensnared in geopolitical tensions between the West and the USSR.

Despite these challenges, Rudolf bided his time, performing with the Marquis de Cuevas and even touring with second-rate cabaret theatres. Then came the pivotal moment that would change the trajectory of his career: an invitation from Margot Fonteyn to perform at a gala event at the Royal Opera House on 2 November 1961.

At the time, Margot Fonteyn was no less than the president of the Royal Academy of Dance and the prima ballerina of the Royal Ballet. Despite the notable age difference—Fonteyn was 42 while Nureyev was just 23—they instantly recognised kindred spirits in each other. Travelling incognito, Rudolf arrived in London and took up residence at the Embassy of Panama.

Their performance at the gala was nothing short of sensational, igniting the stage and capturing the imagination of everyone who witnessed it. This marked the beginning of one of the most iconic partnerships in the history of ballet, a pairing that would defy age, political boundaries, and conventional wisdom to become the stuff of legend.

The real watershed moment in Rudolf Nureyev’s illustrious career came on 21 February 1962 at the Royal Opera House. On this monumental evening, he partnered with Margot Fonteyn to dance the role of Albert in Giselle, thereby giving birth to what would be hailed as the most successful duet in ballet history.

For Margot, the pairing with the young and vivacious Nureyev was rejuvenating. Never before had audiences seen her display such fervour and femininity on stage. Rudolf, on the other hand, found in this partnership a critical cornerstone for his own career. Remarkably, he became the first non-British artist to secure a contract with the Royal Ballet.

Read more: Pyotr Tchaikovsky in London: a journey of impressions, acclaim, and triumph

Over the next seventeen years, Nureyev and Fonteyn’s artistic collaboration would be nothing short of transformative for the world of ballet. Nureyev performed male roles in almost every production the pair tackled together, and his electrifying presence on stage redefined traditional gender roles within ballet. Whereas male dancers had previously served mainly as mere accompaniments to the ballerinas, Nureyev’s performance prowess pushed for men to be given full, independent roles in ballet productions.

This dynamic partnership not only revolutionised the ballet world but also forever etched the names of Rudolf Nureyev and Margot Fonteyn into the annals of performing arts history.

In 1967, Rudolf Nureyev made his first significant foray into the property market, purchasing an 18th-century mansion near the tranquil expanse of Richmond Park. Although he would later accumulate an impressive portfolio of international properties, including luxury apartments in Paris and New York, villas on idyllic islands, and even his own archipelago off the coast of Italy, this Victorian residence marked his first proper home.

With characteristic exuberance, Nureyev transformed the mansion’s six bedrooms and four living rooms, lavishly decorating them in a sumptuous Baroque style. However, despite the grandeur of the home, practicality eventually prevailed. The residence’s distance from the Royal Opera House became a persistent inconvenience for the dancer, who increasingly opted to reside with friends while in London.

Read more: Boris Anrep in London: A Don Juan and the love of Anna Akhmatova

Among these friends were theatre critics Maude and Nigel Gosling, who lived at 27 Victoria Road in Kensington and Chelsea. On the recommendation of Margot Fonteyn, they extended their hospitality to “Rudy,” and he became a frequent guest in their home. Special rooms were designated for his use, and he was a regular at their dining table. After Nigel Gosling’s passing in 1982, this residence became Nureyev’s primary London abode. Today, a memorial plaque on the wall commemorates his connection to this more conveniently located home.

So, while his Richmond mansion stood as a testament to his rise and affluence, it was the more modest Victoria Road residence that offered Nureyev the practical comforts he needed in the city that played such an instrumental role in his artistic journey.

Nureyev’s Lasting Impact and Return to the USSR

Rudolf Nureyev was a restless creative force, always brimming with ideas and rarely pausing for rest. Beyond dancing, he delved into film, appearing in movies like Valentino and Exposed. But his greatest influence might be as a choreographer. His 1964 rendition of Swan Lake at the Vienna State Opera was revolutionary, particularly in how it elevated the male role. Nureyev also breathed new life into ballets like Raymonda and Romeo and Juliet. His leadership from 1983 to 1989 revitalised the Paris Opera Ballet, reinstating it as a global leader in the art form. His legacy endures, immortalised in one of Palais Garnier’s rehearsal halls named in his honour.

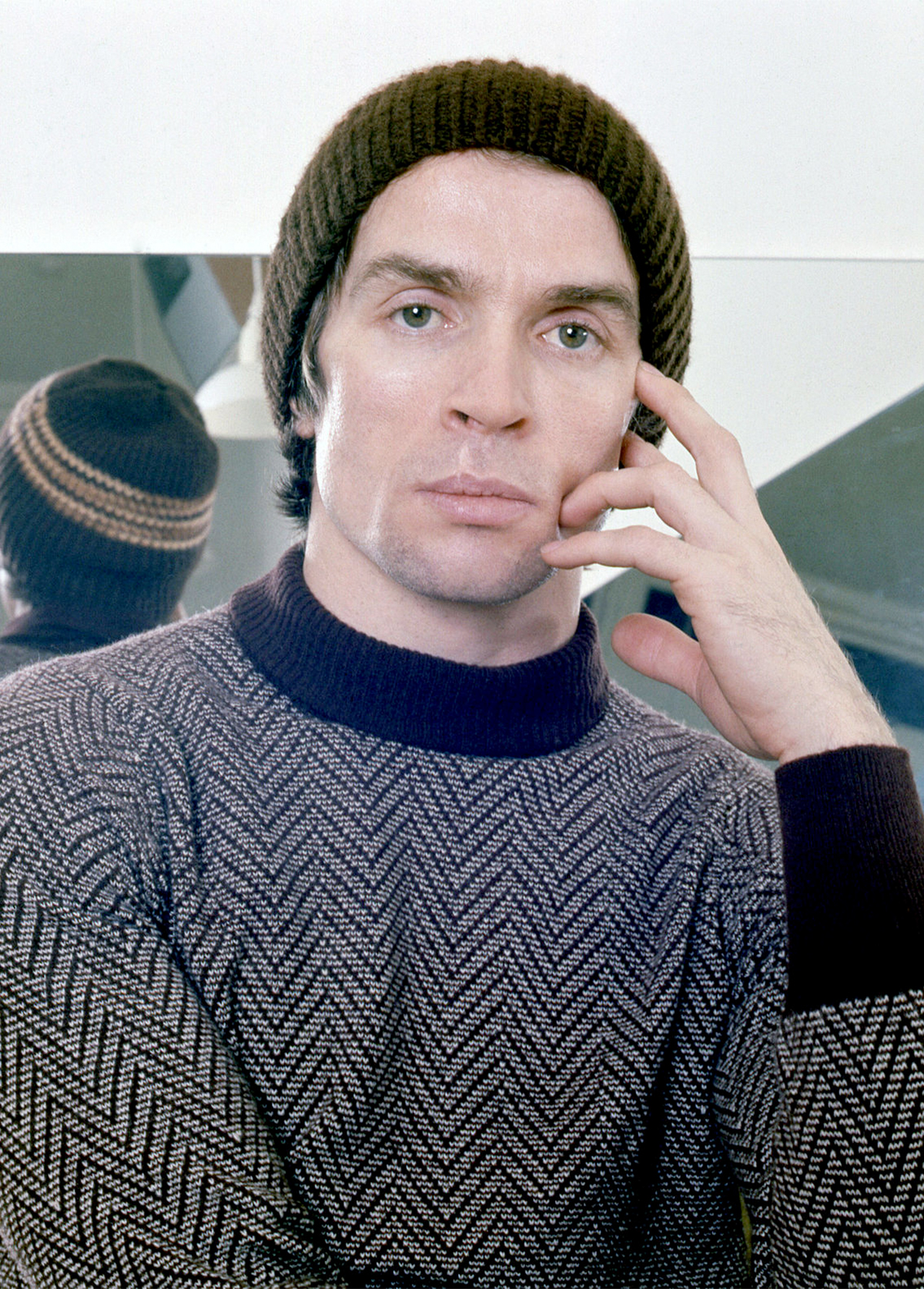

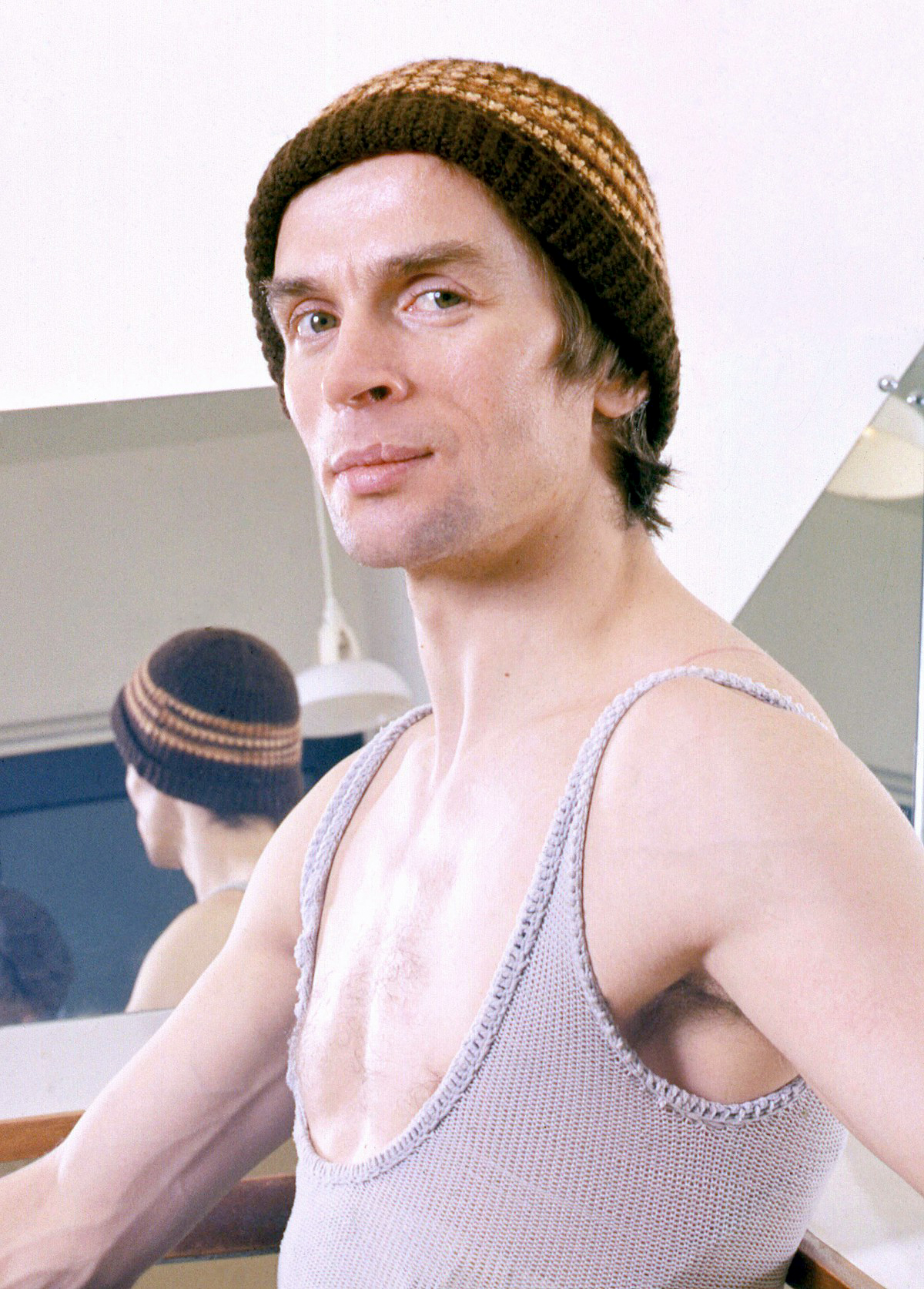

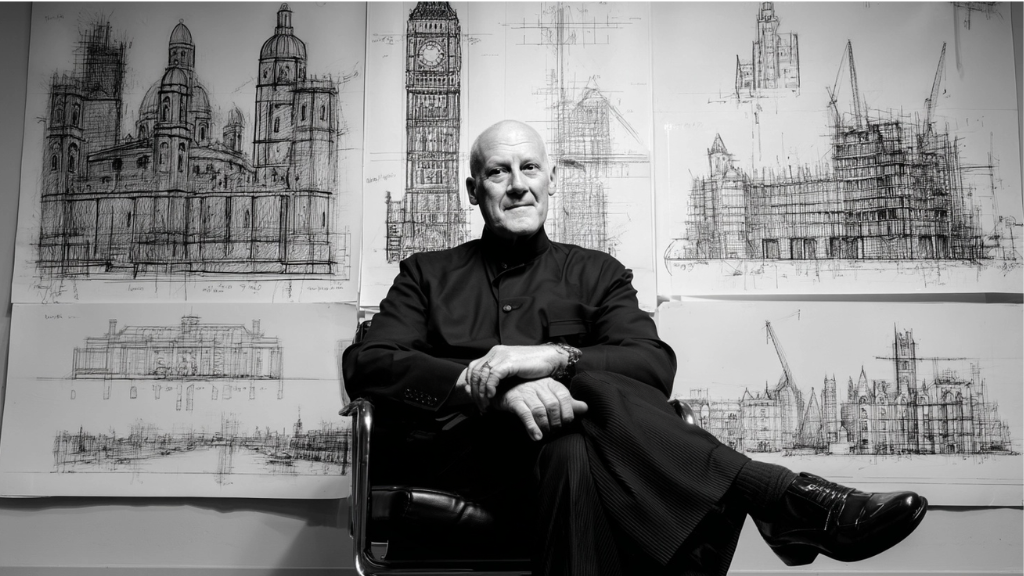

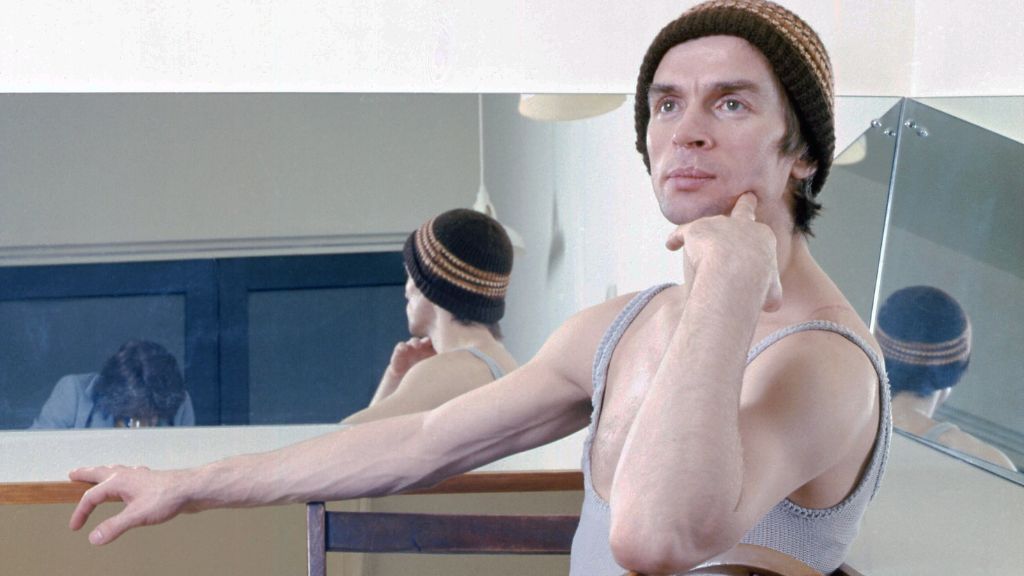

- Rudolf Nureyev in his dressing room at the Royal Ballet School in London (155 Talgarth Road, Barons Court). Photo: Allan Warren, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

- Rudolf Nureyev in London. Photo: Allan warren, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Though Rudolf Nureyev’s name has been romantically linked with figures like Yves Saint Laurent, Elton John, and Freddie Mercury, most biographers concur that his enduring love was Danish dancer and choreographer Eric Brun. Their temperaments complemented each other: Brun’s steadiness balancing Nureyev’s fiery nature. Meeting in the early ’60s, they soon became inseparable, even sharing a flat in Kensington for a period. They maintained a lifelong, trusting friendship even after their romantic involvement ended. In 1986, a sombre Nureyev was by Brun’s side during his final days battling lung cancer. Nureyev faced another emotional blow with the loss of his dear muse Margot Fonteyn in 1991. By that point, he himself was grappling with HIV, and the loss of his two closest companions deeply impacted his already frail state.

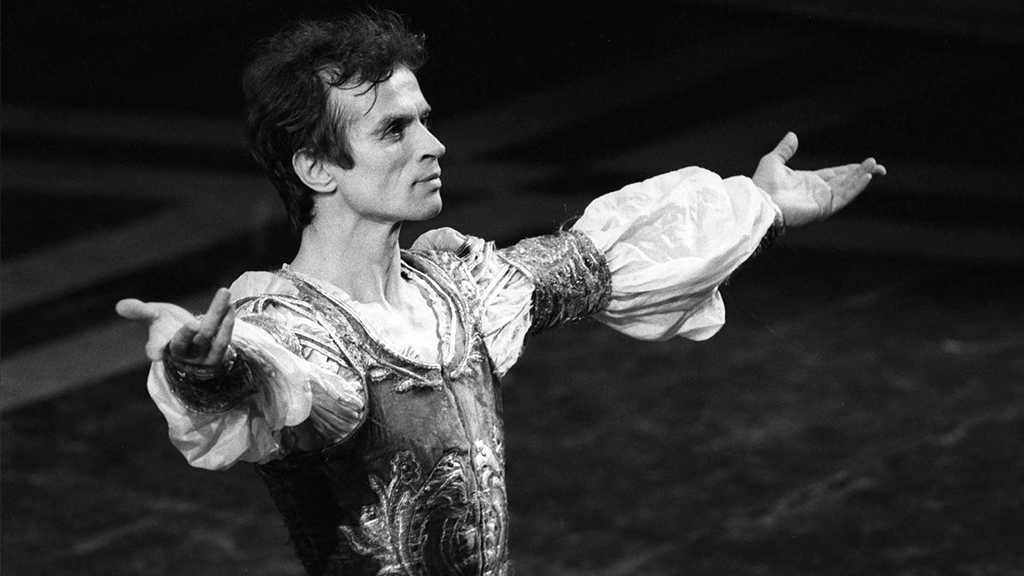

Rudolf Nureyev on the stage of the Kirov Opera and Ballet Theatre (now Mariinsky Theatre) in 1989. Photo: Yury Belinsky

In November 1987, after 26 years in exile, Rudolf Nureyev was granted a brief 72-hour visa to visit his ailing mother in Ufa. The visit was heavily surveilled by the KGB, with every move documented on camera. Although a frail Farida failed to recognise her son, now a striking figure in expensive attire, Nureyev’s first teacher, Anna Udaltsova, warmly welcomed him. Remarkably, his global acclaim was largely unknown in his homeland at the time. Only after the dissolution of the USSR would Nureyev be officially exonerated and recognised as a victim of political repression. This brief, poignant visit served as a testament to the complicated relationship between the artist and the country that had both nurtured and ostracised him.

Rudolf Nureyev conducting at the League Against Cancer concert in Deauville, France (September 6, 1991). Photo: Remy de la Mauviniere/AP

The Final Bow and Lasting Legacy

Until the very end, Rudolf Nureyev remained devoted to the art form that had defined his life. His swansong was the iconic production of La Bayadère at the Paris Opera in 1992. Nureyev succumbed to complications from AIDS on January 6, 1993. He is interred at the Sainte-Genevieve-des-Bois cemetery in Paris, where his grave is adorned with a meticulously designed mosaic carpet, a nod to his Tatar heritage.

Photo: Afisha.London

Much of Nureyev’s property was auctioned off in prestigious sales in London and New York, but his dazzling costumes found a permanent home at a museum in Moulins, France. The British film industry paid homage to him with the poignant 2018 documentary, Nureyev: All the World His Stage. Furthermore, the National Portrait Gallery in London houses an exclusive collection of portraits, ensuring that Nureyev’s visage is immortalised alongside Britain’s most iconic figures. Through his artistry, defiance, and zest for life, Rudolf Nureyev remains an eternal symbol of the transformative power of art over adversity.

Text: Irina Lazio / Translation from Russian: Margarita Bagrova and Liya Shapiro

You may read the version of this text in Russian here

Cover photo: The Rudolf Nureyev Foundation

Read more:

How Britain discovered Gorbachev, and Gorbachev discovered Britain

Felix Yusupov and Princess Irina of Russia: love, riches and emigration

Justine Waddell on launching Klassiki: a streaming platform for Russian cinema

SUBSCRIBE

Receive our digest once a week with quality Russian events and articles