How Britain discovered Gorbachev, and Gorbachev discovered Britain

Оn March 2, 2021 the ex-president of the USSR and Nobel Peace Prize laureate, Mikhail Sergeevich Gorbachev, turned 90 years old. His personal and political lives are closely intertwined with Great Britain, which he for the first time visited back in 1984 and where he celebrated his 80th birthday in 2011. With the help of archival materials, memories of translators and testimonies of contemporaries, we have collected some of the most interesting stories and episodes that connect Gorbachev with London and Great Britain.

“We can do business together”

Towards the end of the five-year ‘funeral’ of the USSR, when the elderly general secretaries were passing away one by one, both in the Soviet Union and abroad the renewal of the Soviet leadership and its course in domestic and foreign policy was highly anticipated. Kremlinologists and Sovietologists in the West paid close attention to the young members of the Politburo, who were slowly beginning to struggle for power. This was when, at the end of 1984, the epoch-making ‘discovery’ of the 54-year-old — young by Soviet standards — politician Mikhail Sergeevich Gorbachev was made. His name was still unknown to British diplomats and government officials, so in the official memoranda from that time, which was declassified a few years ago, it appears in at least three different transliterations into English.

British prime minister Margaret Thatcher, who at that time sought to become a mediator in the possible establishment of a proper relationship between the United States and the USSR, supported the idea of organising Gorbachev’s visit to the UK through the Inter-Parliamentary Union. By that time, Gorbachev had already managed to visit Canada and Italy, and the then Canadian prime minister Pierre Trudeau (the father of the current prime minister Justin Trudeau) subsequently tried to get at least some of the laurels for Gorbachev’s ‘discovery’ in the West, but history decided otherwise.

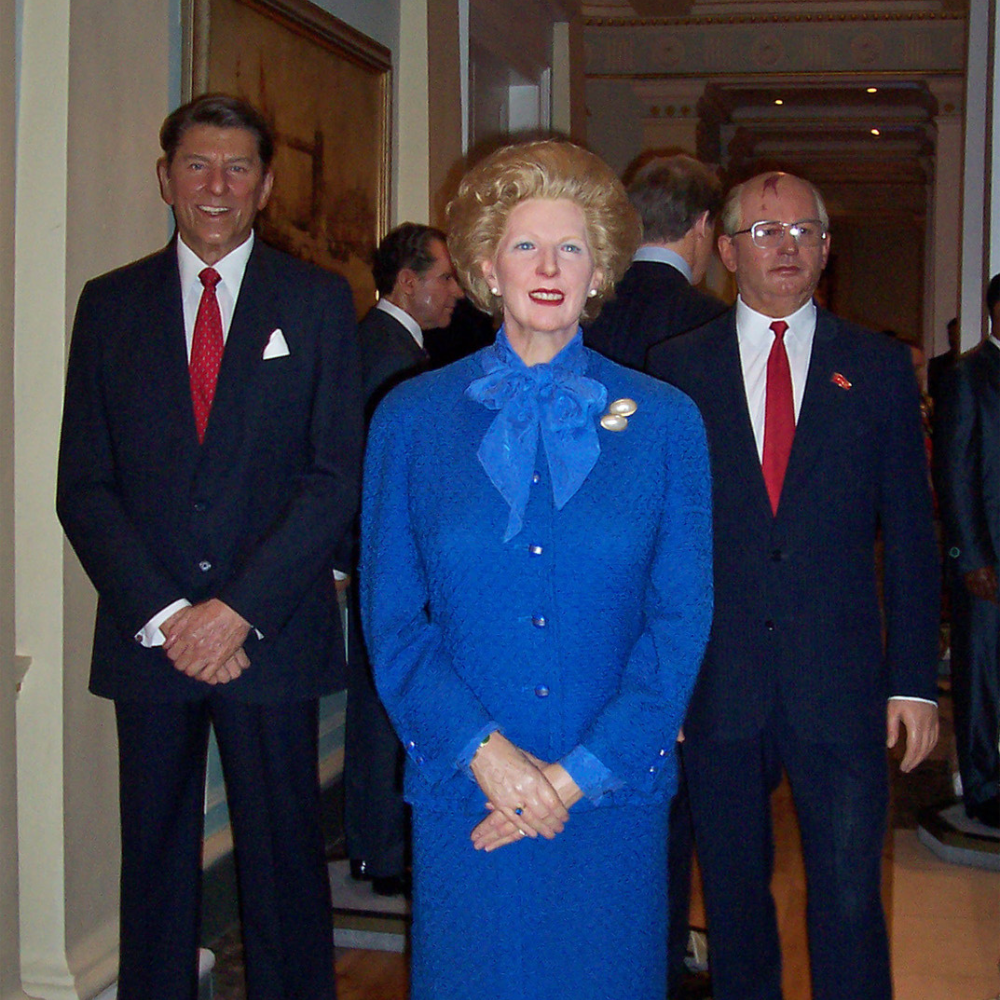

- Ronald Reagan, Margaret Thatcher, and Mikhail Gorbachev at Madame Tussauds London. Photo: InSapphoWeTrust from Los Angeles, California, USA, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

- Visit to Great Britain, 1989. Photo: RIA Novosti archive, image #778094 / Yuryi Abramochkin / CC-BY-SA 3.0, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

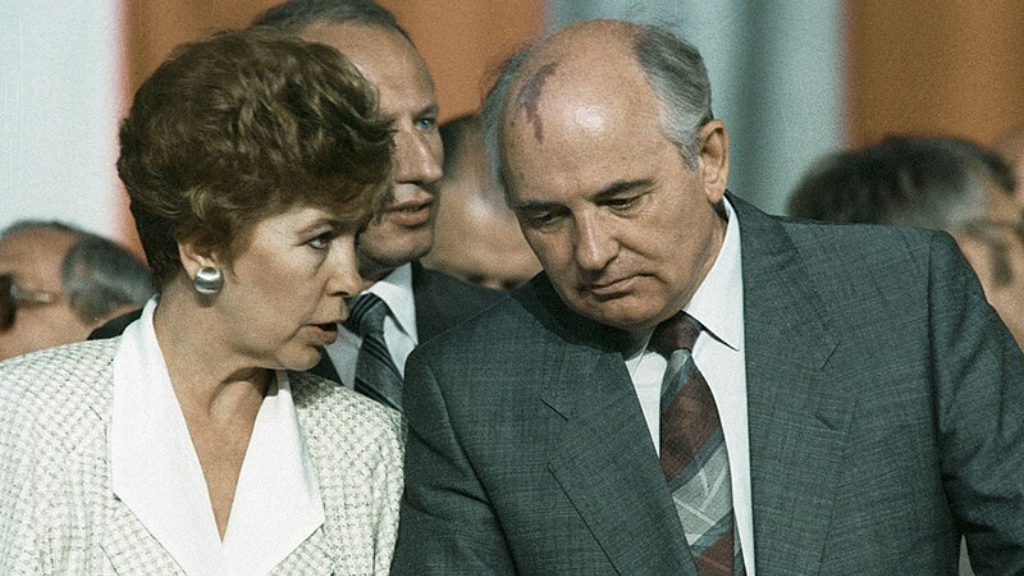

In December 1984, Gorbachev arrived in London, accompanied by his wife Raisa Maksimovna and a delegation of 30 people. The visit lasted a whole week and was conducted to the highest standards, despite its generally not quite official status. Gorbachev met with both British government ministers and Her Majesty’s opposition representatives, visited the Austin Rover car factory and other industrial facilities, talked with businessmen, made a speech in the British parliament and visited Edinburgh. During the visit, he stayed at the Soviet embassy in Kensington, while his delegation remained at the nearby Royal Garden Hotel, where many official guests from Moscow still choose to stay.

The meeting with Thatcher took place in the very beginning of the visit, on December 16, at the Checkers country residence in Buckinghamshire. The recordings of the five-hour conversation indicate that in a discussion with the British prime minister, Gorbachev ‘tested’ his theses on ‘new thinking’, approaches to disarmament and security in Europe, which were to become infamous later, while never deviating from the official Soviet ideological line. His fresh outlook on things, openness and spontaneity impressed Thatcher, and her verdict on the Soviet guest, with whom one can “do business” and negotiate, was later widely replicated as the starting point of Gorbachev’s relationship with the West.

“I am cautiously optimistic. I like Mr. Gorbachev. We can do business together”, — Margaret Thatcher in an interview with the BBC on 17 October 1984.

“I certainly found him a man one could do business with. I actually rather liked him”, — Margaret Thatcher to Ronald Reagan at a meeting on 22 December 1984.

The very next day after meeting with Gorbachev, Thatcher left for a visit to the United States, where she shared her impressions with president Ronald Reagan, while the Soviet guest, who all of a sudden decided to deviate from the official program and visit the prime minister’s residence at 10 Downing Street, had to do so without the hostess. As for other attractions of the British capital, Gorbachev visited the British Museum, in the library of which Lenin was once a regular visitor, and joked that “if people don’t like Marxism, they should blame the British Museum, since that is where it all started”. He also visited the Karl Marx Memorial Library, but did not get to see the grave of Marx at Highgate Cemetery — a mandatory part of the traditional program of Soviet delegations visiting London. As Mikhail Sergeevich himself later recalled in his memoirs: “How much speculation there was later!”.

Raisa and Mikhail Gorbachev, 1988. Photo: RIA Novosti archive, image #28133 / Boris Babanov / CC-BY-SA 3.0, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Raisa Maksimovna managed to visit the Tower of London and inspect the collection of royal regalia and jewellery. By the way, she herself made a strong impression on the British with her education and social skills: while her husband was talking with Thatcher in Checkers, she examined the library of the prime minister’s residence and discussed literature and philosophy with British government officials. Gorbachev himself later admitted that he constantly lacked knowledge of foreign languages, while his wife spoke English and could communicate with Thatcher directly, which Mikhail Sergeevich could not do.

The impressions of the famous translator Tony Bishop, who during his life helped Queen Elizabeth and eight British prime ministers at meetings with Soviet and Russian guests, are quite interesting. In his report on the visit, he notes that Gorbachev was not an ‘intellectual’ in the British sense of the word, but amazed many Britons with his emotional intelligence and spontaneity, including linguistic spontaneity: the ability to quickly ‘switch registers’ in communication and not shy away from colloquial words and expressions such as ‘nonsense’ or ‘clean up the rubbish’. According to Bishop, Gorbachev, in conversations with British politicians, quoted Leskov’s The Tale of Cross-eyed Lefty from Tula and the Steel Flea, recommended organising an exhibition of Ilya Glazunov’s art in London and invited the British to admire Moscow’s Cathedral of the Intercession at Fili.

“Taking an intelligent interest in everything around him, he seemed genuinely impressed both by the British sense of tradition and by examples of British technical innovation (automated insertion windscreen in cars etc.)”, — Tony Bishop, Gorbachev’s interpreter during the 1984 UK visit.

Perhaps some researchers are right to believe that Gorbachev’s visit was given additional significance post factum. “It is hardly worth dramatising this meeting: it was not intended to change history, and if it did, it was due to factors that its participants did not realise at the time”, — notes, for example, diplomat Konstantin Shlykov, who for many years worked at the Russian Embassy in London. But be that as it may, the acquaintance with the future general secretary was successful, personal contact was established and, as the well-known saying “you never get a second chance to make a first impression” goes, Gorbachev and Thatcher took advantage of this very chance.

“Welcome to the club”

Having become the head of the USSR in the spring of 1985, Gorbachev then met with Thatcher on equal terms on numerous occasions, receiving her in the Soviet Union and encountering her at international meetings. The end of the 1980s was filled with dramatic events in Europe and the world, in which both leaders were directly involved, while in the early 1990s, their political careers began to decline. According to the memoirs of Pavel Palazhchenko, Gorbachev’s translator and assistant, which he shared with Afisha.London, Mikhail Sergeevich’s last meeting with Thatcher in official roles took place in November 1990 in Paris at the Second CSCE Summit. Thatcher had to leave ahead of schedule due to an internal political crisis in Britain, which “she was determined to deal with” but which eventually led to her resignation a few days later.

Mikhail Gorbachev and Margaret Thatcher at a reception in Kremlin, 30 March 1987. Photo: Boris Yurchenko/APHS264438

In the summer of 1991, a month before the August Coup, Gorbachev paid a visit to London, where he was invited as a guest to the G7 summit to discuss Western aid to the USSR and the integration of the Soviet Union into the world’s economic and political structures. For Moscow, this was a recognition of its role at a global level long before Russia’s official entry into the G7 and its transformation into the G8. John Major was then the British Prime Minister, but Thatcher came to meet with Gorbachev at the Soviet embassy as a private individual. During the Coup, she publicly defended Gorbachev, saying that he “has brought new hope to the Soviet people… he brought new hope to the world”. On the day of his resignation from the post of President of the USSR, she spoke warmly on her behalf as well as on behalf of Ronald Reagan about their relationship and joint achievements, perhaps secretly being proud of the fact that her mediating role was generally a success.

“I think together we could probably do more things than we could separately… We were a threesome, and I hope that together we managed to do quite a lot for peace and democracy”, — Margaret Thatcher remarks on the resignation of Mikhail Gorbachev as Soviet leader, 25 December 1991.

Thatcher will then come to the opening of the Gorbachev Foundation in Moscow, and her close personal relationship with the last leader of the Soviet Union will continue for many years. Paradoxically, the two politicians are also related by the fact that in their homelands the public still treats them and their political heritage with much more criticism than the international community.

A frequent guest in Britain

After leaving the post of President of the USSR Gorbachev visited the United Kingdom more than once, often passing through on his way to America and back. He met with almost all subsequent British prime ministers: Tony Blair, Gordon Brown and David Cameron, discussing Russian-British relations and international problems. They met with Brown at the beginning of his premiership, when relations between Russia and Great Britain seriously deteriorated due to the Litvinenko affair, and, according to the memoirs of Gorbachev’s companions, Brown asked for a very hearty breakfast, so he had a lot to digest, both literally and figuratively.

Meetings with Thatcher continued, too. One of them, according to the British press, took place during dinner at The Ivy, while the other was timed to coincide with the ex-Prime Minister’s 80th birthday. As Pavel Palazhchenko recalls, during the conversation Thatcher suddenly asked Gorbachev whether he would like to go back to ruling, considering how current politicians lack leadership qualities and make few wise decisions. The ex-president politely said something in the spirit of giving a chance to the current generation of leaders, to which Thatcher firmly replied: “But I would gladly!”.

For several years in a row Hampton Court Palace hosted regular charity evenings organised by the Raisa Gorbacheva Foundation, the purpose of which was to aid the fight against cancer in Russia and the UK. Alexander Lebedev, Gorbachev’s friend and business partner (they are both minority shareholders of the Russian newspaper Novaya Gazeta), helped with organising these evenings, while Boris Johnson, who was then Mayor of London, was among the guests.

According to Palazhchenko, Gorbachev tried to find time to get to know the city, which did not always work out because of the dense program, although sometimes there were additional opportunities, such as flight delays or other similar circumstances. Whenever Gorbachev visited historic sites, such as Westminster Abbey, Windsor Castle, Guildhall or Hyde Park, he was always left very impressed.

“He was respectful not only towards people, but also towards countries… He very much feels the historical culture. This is a person who, having come from the working classes, eagerly absorbed all that he missed in his youth, including that which concerned the West”, — Pavel Palazhchenko, Gorbachev’s translator, press secretary of the Gorbachev Foundation.

Birthday concert at the Royal Albert Hall

In 2011, Mikhail Sergeevich celebrated his 80th birthday twice: first in Moscow and then in London, where a grandiose charity concert was held in his honour at the Royal Albert Hall. It was opened by the legendary German band Scorpions with the song Wind of Change, personifying the fall of communism in Eastern Europe, in which Gorbachev played a key role. Then for four hours on the stage of the almost completely filled hall, performed such famous artists as the London Symphony Orchestra conducted by Valery Gergiev, Dmitry Hvorostovsky and Igor Krutoy, Catherine Jenkins, Lara Fabian, Shirley Bassey, Mel C, Brian Ferry and the Turetsky Choir. The evening ended with a specially prepared performance — song Changing the World for Us All sang by Andrey Makarevich and Paul Anka.

Also, during the concert the award “The Man Who Changed the World” was presented to outstanding figures of our time in the nominations named with the words popularised by Gorbachev: ‘Perestroika’, ‘Glasnost’ and ‘Uskoreniye’. Among the laureates were the inventor of the World Wide Web, Sir Timothy Berners-Lee, and the founder of the CNN television channel and the Goodwill Games, Ted Turner. Speaking to the guests, Gorbachev himself admitted that he expects to live to at least 90 years old and considers himself a happy person. He also said that he is delighted to celebrate his birthday in the building, which is a “monument of love” (referring to the history of its construction by Queen Victoria in memory of her husband), and asked that the celebrations for his 90th birthday be arranged more modestly.

His wishes came true. Due to the pandemic, Gorbachev’s 90th birthday celebrations was much less lush, though no less warm and meaningful. He passed away a year later, in 2022.

Alexander Smotrov

Cover photo: Mikhail Gorbachev and Margaret Thatcher in London, 15 December 1984 (Gerald Penny/Associated Press)

Read more:

Felix Yusupov and Princess Irina of Russia: love, riches and emigration

SUBSCRIBE

Receive our digest once a week with quality Russian events and articles