Ballerina Anna Pavlova: a beautiful swan of two empires

Anna Pavlova is one of the greatest ballerinas of the 20th century, who made the whole world fall in love with Russian ballet. Her mysterious smile, incredible grace and phenomenal work ethic made Pavlova a true inspiration for everyone lucky enough to see her dance. Exquisite perfumes and dreamy desserts were created in her honour, while concert halls throughout the world applauded her and monuments to the ballerina were erected long before her death. Meanwhile, Anna’s life was divided between two empires. Her career flourished with the “swan dance” in St. Petersburg, but it was in London where Pavlova found happiness and started her own ballet studio. Afisha.London magazine follows the life of the most famous “swan” of Russian ballet, who found her second home in the United Kingdom.

Persistence and incredible dedication to the chosen path distinguish Anna Pavlova’s story from all others. Her brilliant career began in her hometown of St. Petersburg, a city which to this day honours the places connected to the ballerina with memorial plaques. There she for the first time performed the famous The Dying Swan, which captured the hearts of the audience, and met her one and only love, Baron Victor Dandré, who became a key figure in her life. After the outbreak of World War I in 1914, Anna moved to the United Kingdom and began a new period in her life. London became a safe haven for her and a place where she finally had the long-awaited reunion with her loved one. In a luxurious mansion in Golders Green, a stronghold of art and science, Pavlova trained young ballerinas and rehearsed with the troupe, while also taking care of a garden and a pond, where her beloved swans gracefully glided across the water.

- Anna Pavlova in 1905. Photo: "Ришар" фотоателье, СПб., Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

- Anna Pavlova in 1913. Colourisation: Klimbim

First timid dreams

The future ballet star was born on February 12, 1881 in a military hospital in St. Petersburg. Her mother was Lyubov Fedorovna, a washerwoman, and her father was a soldier of the Preobrazhensky regiment, Matvey Pavlov. According to the official version, Pavlova’s father died when the girl was 2 years old, but rumours persisted that Anna, in fact, was the daughter of a Jewish banker who did not want to officially recognise his child. The pain of feeling useless pushed Pavlova to pursue her goal of becoming a brilliant ballerina with unswerving persistence. We will never know whether this really was the case, but, regardless, the strength of character with which the girl overcame her own weaknesses truly had no bounds.

Since birth Anna had poor health, so Lyubov Fedorovna had to regularly take her daughter to a village near St. Petersburg. Now this place is no longer a village but a district of the ever-growing city, but back then, in the 1880s, the healing clean air significantly helped strengthen the girl’s health. Pavlova’s contemporaries wrote in their memoirs that life in the village gave the impressionable Anna an understanding of nature that deeply touched her soul. During her next trip to St. Petersburg little Anna went to see Sleeping Beauty and with absolute awe admired the beautiful ballet dancers almost floating above the surface of the stage. Theatre forever stole her heart. From that day on the young lady did not want to think about anything except attending a ballet school.

Birth of a star

At the age of ten Pavlova entered the Imperial Ballet School, which is now known as the legendary Vaganova Academy of Russian Ballet in the very centre of St. Petersburg. Anna later compared the atmosphere at the school to a monastery — the strict discipline and daily exercise hardened the young ballerina, erased her childish stoop and made her body strong. After graduating from the Academy with honours, in 1899 Anna received an invitation to join the Mariinsky Theatre’s troupe.

- Anna Pavlova in Les Sylphides (1909) Photo: Unknown photographer, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

- Anna Pavlova at the Ball in Berlin (1928). Photo: Unknown photographer, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

In the eyes of ordinary spectators, the Mariinsky Theatre was akin to the summit of Mount Olympus, but the intrigues that reigned behind the scenes of this symbol of Russian theatrical culture were quite earthly. Through the efforts of prima ballerinas, many talented artists “stood by the water” all their lives — they danced in the last rows of the corps de ballet. However, such fate was not for Pavlova. At first, critics noticed her strange technique — it was more like improvisation. Anna, gracefully fluttering across the stage, performed each dance differently. Then the audience liked the plasticity and emotionality of the talented ballerina, and her style was considered individualistic. On the stage of the Mariinsky Theatre Pavlova performed Giselle, Swan Lake, Sleeping Beauty, Don Quixote, Le Corsaire, The Pharaoh’s Daughter, La Bayadère and other famous ballets.

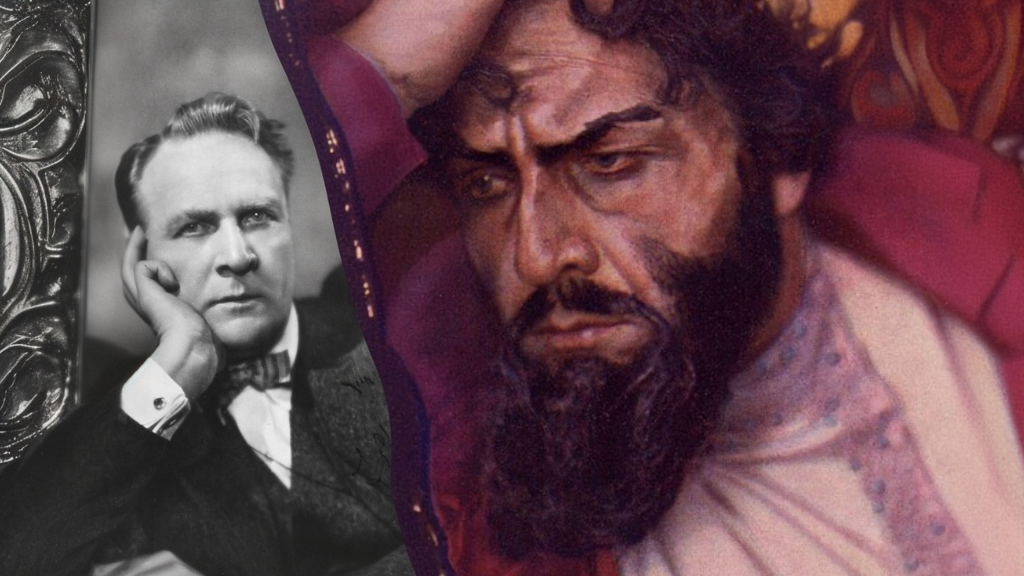

Anna meets her one and only love

Anna met him in the beginning of her career. The handsome and wealthy state councillor, Baron Victor Dandré, came from an old noble family and was a passionate ballet lover. At the time, it was prestigious at the Imperial court to patronise ballerinas, and among the aspiring artists Victor noticed Pavlova. Anna was not spoiled by the attention of fans — she devoted all her strength and time to rehearsals and performances. The ballerina liked to repeat: “I am a nun of art. Personal life? It is theatre, theatre, theatre!”

Her relationship with Dandré was really like a theatrical performance about tragic and all-consuming love. The baron showered Anna with flowers and gifts, paid for her costumes and rented a luxurious apartment in the city centre with a built-in dance hall for rehearsals, which was an utter luxury. But the brighter her fame, the more Anna thought that for Victor she was just an expensive toy. A descendant of a noble family could not officially connect his life with an ordinary ballerina. For the proud Pavlova, this was offensive.

Anna expressed her pain in the only way she could — through dance. On January 4, 1908, at a charity concert at the Mariinsky Theatre Pavlova performed a miniature called The Swan, which was staged by her old friend, partner and choreographer Mikhail Fokin. In this dance-monologue she was so organic and inimitable that she captivated the most discerning critics. The plasticity of movements and the bottomless sadness of the dance reflected the whole gamut of her accumulated feelings. Anna confessed her hopeless love to the whole world. The Swan later turned into the legendary The Dying Swan, and from that moment on, the prima ballerina of the Mariinsky Theatre was recognised as the main star of Russian ballet.

Read more: Rudolf Nureyev: an emigrant, who became a ballet legend

A new role for the Russian Swan

Thanks to Victor, Anna got acquainted with Sergei Diaghilev — a major figure in the theatre world and a propagandist of Russian ballet in Europe at the beginning of the 20th century. In 1909, Pavlova was dazzling in his famous Ballets Russes in Paris, after which the entire world was open to her. Abroad she was called the “Russian Swan”. Anna parted with Baron Dandré, but, apparently, one cannot escape their fate. While Anna was touring abroad, Victor was arrested — he was charged with taking a bribe. According to rumours, it happened because in his efforts to make Pavlova a star, he crossed paths with another famous ballerina and the favourite of the Emperor, Matilda Kshesinskaya.

Anna Pavlova and Mikhail Mordkin (1910). Photo: University of Washington, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Coincidence or not, it was at this time that Anna resigned from Diaghilev’s troupe. For a huge fee of £1,200 a week, the ballerina performed on the stage of the London’s Victoria Palace Theatre in an unexpected and shocking role. Tanned, in an outfit that reveals more to the audience than it should, with a crazy smile and great enthusiasm, she performed funny dances and participated in shocking stunts. She was in desperate need of money. London’s conservative public went to see the famous Anna Pavlova with surprise and great pleasure. Anna performed in tandem with the brutal handsome dancer Mikhail Mordkin — their bright creative duet excited the interest of the audience and was all over the headlines. Even the Prince of Wales and his family once attended a show.

- Anna Pavlova and Mikhail Mordkin (1910). Photo: University of Washington, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

- Anna Pavlova and Mikhail Mordkin in New York (1910s). Photo: V&A

In October of 1911, Anna agreed to Diaghilev’s offer and performed the title role in Giselle, when the Ballets Russes toured in London, delighting the British audience by appearing in a role worthy of her status of a great ballerina. The fees she received for her performances were enough to pay off Dandré’s debts and to save up for her own house. Then Pavlova once again made an unexpected gesture — she summoned Victor to her place in London.

The amazing Ivy House

London welcomed the ballerina, and she, so it seems, finally was in control of her own life. In 1912, Anna purchased the luxurious Ivy House in the scenic Golders Green at 94-96 North End Road and spent nearly 20 years there. The ballerina did not choose Ivy House by chance: in the 19th century the two-storey mansion with an old garden and a pond belonged to J. M. W. Turner. The personality of the former owner and the surroundings of the estate with a beautiful view of the British capital fuelled Anna’s vivid imagination. Today the mansion continues being a cultural centre to this day by hosting the Jewish Cultural Centre. According to tradition, a blue plaque in honour of Pavlova is installed on the building, which is difficult to notice right away, since it is hidden on the side.

Wide windows and spacious rooms of the mansion delighted the ballerina. Since constant tours did not allow her to rest for a long time, Anna especially appreciated the minutes of calm and solitude. Her favourite resting place was the living room, where a floor-to-ceiling window overlooked the garden. Pavlova transported some of the interior and dear things from St. Petersburg, and after 1914 she never returned to Russia. Victor Dandré came to Ivy House with forged documents, becoming Anna’s husband and impresario. They switched roles — now Anna set the rules. Dandré took over the household chores and dutifully listened to the numerous whims of his wife. There the ballerina set up her own studio, where she taught young students, rehearsed with the troupe and met with friends. Her main inspiration was the swans in the pond and, in particular, her favourite swan, Jack, with whom the ballerina loved to pose for photographs.

A beautiful legacy

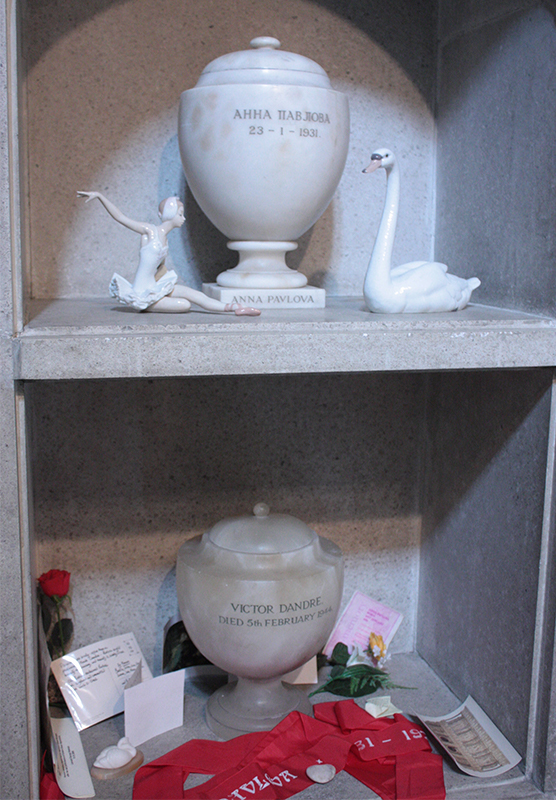

Anna Pavlova’s life ended in The Hague on January 23, 1931, where she was on tour and caught a bad cold. The art world lost a great artist, but Dandré grieved most of all. The two lovers are still together — urns with their ashes are in the Golders Green mausoleum.

- A gilded sculpture of Anna Pavlova on top of the Victoria Palace Theatre. Photo: Acabashi, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

- Urn with the ashes of Anna Pavlova above the urn with the ashes of Victor Dandré in the Golders Green mausoleum. Photo: Stephencdickson, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The British capital cherishes Anna’s legacy. While walking around London and passing by the Victoria Palace Theatre, look up — the dome of the building is proudly crowned with a gilded sculpture of a ballerina. In turn, the capital’s restaurants serve their own version of the famous New Zealand dessert “Pavlova”, which combines meringue with cream and strawberries. As airy and inviting as the dance of the star of Russian ballet.

Irina Latsio/Liya Shapiro

Cover photo: Anna Pavlova in costume for The Dying Swan (colourisation: Kimbim)

Read more:

Swan Lake: Unusual Interpretations of the Timeless Classic

Felix Yusupov and Princess Irina of Russia: love, riches and emigration

Lydia Delectorskaya: the Russian émigrée who transformed Henri Matisse’s life

SUBSCRIBE

Receive our digest once a week with quality Russian events and articles