What connects popular Maria biscuits with the wedding of a Russian Grand Duchess and the Duke of Edinburgh

Everyone is familiar with Maria biscuits — those round, flat crackers that have become a staple treat in countless households. But have you ever wondered who the Maria behind the name really was? The team at Afisha.London found this story too intriguing to ignore, so we conducted a deep dive and uncovered a wealth of fascinating details. Discover the tale of how Russian Grand Duchess Maria Alexandrovna married the Duke of Edinburgh, and how, in celebration of their wedding, a recipe for the perfect biscuit was created in London.

A recipe of the century for an unexpected union

London, 1874. Queen Victoria was in a state of indignation, while courtiers whispered in the shadows — Alfred, her second son and a proud naval officer, had chosen a bride. His chosen one was none other than Grand Duchess Maria Alexandrovna, the beloved only daughter of Russian Emperor Alexander II. The intrigue lay in the fact that not long ago, the Crimean War had ended, leaving relations between the Russian and British Empires strained at best. Both nations stood at the height of their power, and neither monarch was willing to bow to the other’s demands. Alexander II insisted on a dual wedding ceremony in St. Petersburg — first according to the Orthodox rite, and then in the Anglican tradition. With a heavy heart, the British queen reluctantly agreed, though she refused to attend the ceremony in Russia. Maria, as a daughter-in-law, was far from what Victoria had envisioned. Raised in luxury and affection, the Grand Duchess had grown into a bold and free-spirited young woman, a stark contrast to the rigid Victorian morals of the British court. Yet the conflict between these two formidable women was still on the horizon, while the preparations for the grand wedding were already in full swing.

The wedding ceremony was set for January 23, 1874, at the Winter Palace in St. Petersburg, and among the gifts from the British side was to be a delightful new biscuit. The recipe was entrusted to the family-run bakery Peek Freans, based in the Bermondsey district of London. The bakery was already renowned for creating Garibaldi biscuits, named after the Italian general Giuseppe Garibaldi, a key figure in the unification of Italy. For the occasion of the Russian duchess’s marriage to the English duke, the bakers modified the popular British “Rich Tea” biscuit — removing the malt and replacing it with vanilla.

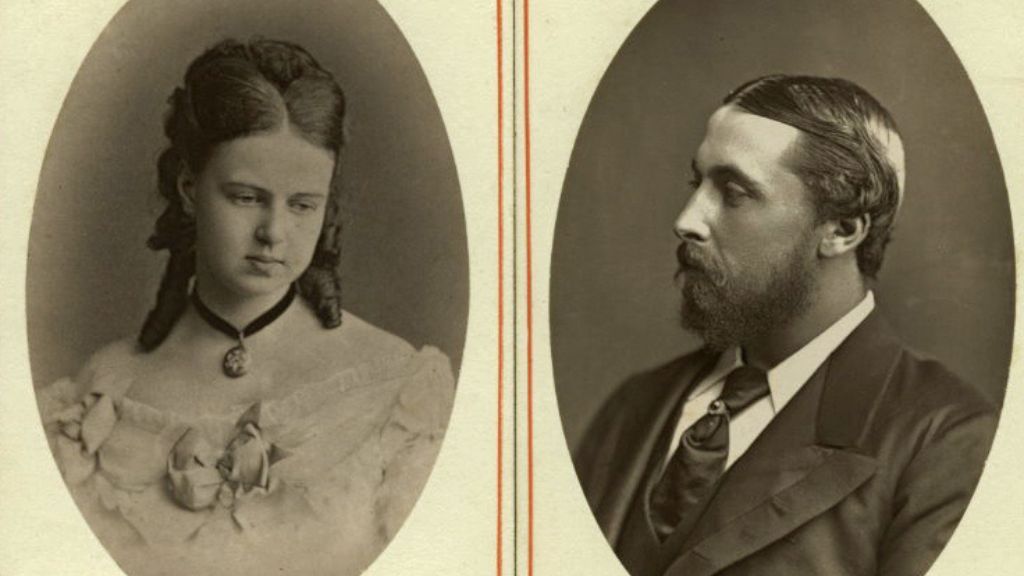

- Grand Duchess Maria Alexandrovna. Photo: Charles Bergamasco, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

- Prince Alfred. Photo: photographie, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The resulting round biscuits were perfect for dipping into tea or milk, softening without losing their shape. The new recipe was named after Grand Duchess Maria Alexandrovna, and it became an instant success. The name “Maria” resonated across many languages, carrying familiarity and special significance for most people, as it was the name of the mother of Jesus Christ. This connection helped the biscuit quickly find a home in Spain and other countries around the world, even though it may have different name variations such as Marie, Mariebon, and Marietta.

The story of Alfred and Maria

Alfred, Duke of Edinburgh, was a highly eligible bachelor — it’s no wonder that Queen Victoria was particularly meticulous in choosing a bride for her son, rejecting potential candidates for anything from imperfect teeth to inadequate dowries. In 1856, at the age of 12, Alfred entered the Royal Navy as a cadet and, within ten years, rose to the rank of captain. However, his military accomplishments were often overshadowed by the titles generously bestowed upon him by his reigning mother. In 1866, Victoria appointed Alfred, affectionately known as “Affie,” as the Duke of Edinburgh, Earl of Ulster, and Earl of Kent, and granted him an annual allowance of £15,000 (£15,000 in 1866 is worth £2,237,584 today)

Read also: Nicholas II and George V: A History of Friendship and Duty

The following year, Alfred embarked on a round-the-world voyage, becoming the first member of the British royal family to visit Australia, which was then a British colony. While there, he narrowly escaped death after being shot by an Irish nationalist, Henry O’Farrell. In honour of the Duke’s recovery, a hospital was built — today, the Royal Prince Alfred Hospital continues to serve as one of Sydney’s oldest and most renowned medical institutions.

How Alfred and Maria looked like when they first met. Photo: Archives of the Russian federation, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Meanwhile, Queen Victoria had already set her sights on a bride for her son: Princess Dagmar of Denmark. However, in 1866, Dagmar married the future Emperor Alexander III of Russia and became Empress Maria Feodorovna. Undeterred, the British queen continued corresponding with various European royal families in her search for a suitable match, when Alfred surprised her with the news that he had found a bride on his own.

Read also: Anna Akhmatova in the UK: A Poetess, Muse and Femme Fatale

In August 1868, he was visiting his sister, Princess Alice, in Heidelberg, where he met Russian Grand Duchess Maria Alexandrovna, who was just 15 at the time. The Duke was immediately taken with her, but the young Maria found his forwardness and lack of decorum somewhat overwhelming. Having spent so much time at sea, Alfred had grown unaccustomed to the refined manners of high society, feeling more like a seasoned sea captain than an aristocrat.

Three years later, they met again in Darmstadt, and this time, Maria was more receptive to his advances, even promising to consider his marriage proposal. Emperor Alexander II was fond of Alfred and recognised that the Duke would be a brilliant match for his daughter, but the final decision lay with Maria herself. In the summer of 1873, Alfred travelled to St. Petersburg, where he received the long-awaited “yes” from the Grand Duchess.

- Maria Romanova with her fiancé, father Alexander II and brother Alexei. Photo: W. & D. Downey, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

- Alfred and Maria, engagement. Photo: Franz Backofen, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Here, it’s worth saying a few words about Maria, who had such a headstrong and even haughty character that her parents had nearly given up hope of finding her a husband. The Grand Duchess had been spoiled from childhood, as her very birth had brought immense joy to the imperial family. After the early death of their first daughter, the imperial couple had only sons, and it was not until the Empress’s fifth pregnancy that they finally welcomed the long-awaited girl.

Anna Tyutcheva, a former lady-in-waiting to the Empress and Maria’s governess, lamented that Maria would grow up to be too self-centred, and she was not wrong. The cherubic child blossomed into a blue-eyed beauty, but she rejected every suitor who sought her hand, deeming them unworthy of her.

It was a surprise to all when she agreed to marry the English Duke, but Maria adamantly refused to consider any other candidates.

A dream wedding in Russia and life after marriage in England

In January, noble guests arrived in snow-covered St. Petersburg — Alfred’s brother Bertie, the future King Edward VII, with his wife Alexandra, his sister Victoria with her husband Friedrich, the Crown Prince of Prussia, and another brother, Arthur. Since Queen Victoria refused to travel to Russia, Alfred commissioned artist Nicholas Chevalier to create a series of watercolour sketches of the celebration to show his mother. The first ceremony, following the Orthodox rite, took place in the court chapel of the Winter Palace, followed by a second ceremony in another hall, where a priest from Westminster Abbey blessed the couple.

After the formalities, a grand banquet was held for 700 guests, followed by a ball in the Throne Hall for 3,000 attendees — the wedding of the Grand Duchess and the English Duke became the highlight of the year. Chevalier created numerous sketches and later combined them into a painting titled «The Marriage of Prince Alfred, Duke of Edinburgh, and Grand Duchess Maria Alexandrovna». The artist meticulously captured the richly gilded decorations of the Winter Palace chapel, the bride’s gem-encrusted brocade sarafan-dress, and the groom’s officer’s uniform. The painting was splendid, and the sketches were preserved and later exhibited in 2018 at the «Russia, Royalty & the Romanovs» exhibition in the Queen’s Gallery at Buckingham Palace.

«The Marriage of Prince Alfred, Duke of Edinburgh, and Grand Duchess Maria Alexandrovna» by Chevalier. Photo: NICHOLAS CHEVALIER (1828-1902), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Maria was a wealthy bride with a substantial dowry — Emperor Alexander II provided an unprecedented sum of £100,000 (around £14,170,000 today) for his daughter and granted her an annual allowance of £20,000 (around £2,834,000 today). Along with this came chests filled with dresses, carpets, gold tableware, and even furniture. Clarence House, where the newlyweds were to reside, was meant to be as cosy and lavishly decorated as Maria’s beloved Winter Palace.

Read also: Ivan Turgenev’s Sojourn in London: a literary ambassador between the Russian Empire and the West

However, England disappointed Maria. She found herself disheartened by almost everything, from the gloomy weather and courtly customs to the attitude of Queen Victoria. In retaliation, Maria often sought ways to vex her mother-in-law. For instance, after the birth of her first child, she would breastfeed in the presence of the Queen and other guests without hesitation, fully aware that the sight of breastfeeding made Victoria and her prim courtiers uncomfortable. Another of Maria’s amusements was flaunting her Russian jewellery, teasing the royal court with gems few could match in splendour.

Over time, however, Victoria came to accept her strong-willed daughter-in-law. The Queen began to see in Maria a strength of character and poise that ultimately commanded respect.

Alfred, Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, at Rosenau with his wife, their four daughters and Alexandrine, dowager duchess of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha. Photo: majesty magazine, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Yet Maria’s relationship with Alfred, on the other hand, took a turn for the worse. Despite having five children — one son and four beautiful daughters — the Duke of Edinburgh was far from an ideal family man. He spent long periods away at sea, and in 1893, after the family moved from London to Coburg, their eldest son, Alfred Jr., fell into a life of debauchery and contracted syphilis. Unable to bear the shame, he attempted suicide, but instead gravely injured himself and died two weeks later. After the death of his son, the Duke turned to heavy drinking and eventually passed away in 1900. Maria, now widowed, outlived him by 20 years. With the outbreak of World War I, she relocated to Switzerland with her daughters, supporting herself by selling her exquisite jewellery.

Invalid slider ID or alias.

The Legacy of Maria Biscuits in Spain and Beyond

While the fate of Grand Duchess Maria was far from sweet, the biscuit named in her honour fared much better. The simple and inexpensive Maria biscuit recipe spread across British colonies and Europe, and in Spain, it was adopted by the family bakery Fontaneda. Eugenio Fontaneda and his son Rafael from the town of Aguilar de Campoo devoted their entire factory to the production of Maria biscuits — and it paid off. When the Spanish Civil War broke out in 1936, times were tough, and demand for long-lasting, affordable biscuits that could be stockpiled only grew. During the war, Rafael managed to navigate the regime of Francisco Franco, expanding production, and by the mid-20th century, Maria biscuits had become a staple breakfast item in nearly every Spanish household. Fontaneda company still exists on the market.

- Photo: Pixabay / Pexels

- Maria biscuits are included in many recipes. Photo: Arina140302, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Riding this wave of popularity, the biscuit made its way to Latin America and the United States, where it was often mistaken for a Spanish creation. Meanwhile, in Spain, production expanded as factories like Galletas Gullón and Galletas Fontibre joined in. In the Soviet Union, Maria biscuits were produced by the “Bolshevik” factory, and today in Russia, around 10 different companies continue to make these round crackers. Even now, Maria biscuits remain a beloved treat, with production taking place in 45 countries around the world.

Irina Lazio/Margarita Bagrova

Cover photo: Midjourney / Afisha.London

Read also:

Felix Yusupov and Princess Irina of Russia: Love, Riches and Emigration

How Diaghilev’s “Saisons Russes” influenced the European art world of the 20th century

Leo Tolstoy in London: shaping the british literary landscape

SUBSCRIBE

Receive our digest once a week with quality Russian events and articles