The history of crystal: how an English invention thrived in Russia

Did you know that the history of crystal production is a true adventure story in the quest for the secret formula that made crystal so coveted by aesthetes worldwide? Afisha.London recounts how the commercial secret of glass-making passed from Murano masters to an English merchant who became the inventor of crystal, and how the formula he discovered led to the production at a Russian factory in Gus-Khrustalny.

A visit to Venetian masters

The history of crystal begins in medieval Venice. Where else, but in this oasis of beauty and art, could an invention arise that would captivate the entire world? In the 13th century, Byzantine masters fled the captured Constantinople, bringing with them the secret technology of producing painted glass, and settled in Venice. Their knowledge allowed them to create not ordinary glass, but unique specimens of various colours and shapes.

By the late 13th century, there were so many workshops and furnaces blazing with fire for glass production that the authorities became concerned about fire safety. It was then decided to relocate all the masters to a separate island, which eventually became legendary — Murano. However, they were forbidden to leave the island. If a master did leave, their relatives were taken into custody and tortured, and a hired assassin would be sent to demand the fugitive’s return. Historians believe that artisans were intentionally isolated on the island and subjected to strict rules to ensure they would not divulge the commercial secret of glass production. For Venice, this secret was a gold mine.

Murano Island. Photo: Balint Miko on Unsplash

On the island, the masters honed their craft, creating coloured vases, decorations, tableware, chandeliers, and much more. The business gained incredible momentum, and Murano glass became a dream for many around the world. Venice’s location at the crossroads of trade routes between East and West helped establish a monopoly on glass sales throughout Europe. Glassblowers earned high wages and enjoyed privileges. For example, the daughters of craftsmen could expect to marry heirs of noble and wealthy families. The secrets of glass production were kept within families, and the craft was encouraged to be passed from father to son. In the 15th century, artist Angelo Barovier discovered the technology for transparent glass, and Murano glassblowers became the sole producers of mirrors in Europe. They also created glass imitating popular Chinese porcelain, gilding, semi-precious stones, and craquelure. A true novelty was mosaic glass with a floral pattern in the millefiori technique (from Italian “millefiori” meaning “a thousand flowers”), which was known as far back as Ancient Egypt.

The creation of “lead crystal” in London

How the Englishman George Ravenscroft managed to uncover the carefully guarded secret of Murano masters remains a mystery. However, it was he who transported the commercial secret of glass production from Venice to England and founded his own crystal production. In his youth, George had planned to become a clergyman and attended an English college, but he changed his mind and retrained as a merchant. From 1651 to 1666, Ravenscroft lived in Venice, trading glass and knowing all the local glassblowers. During his time with the masters, he learned which additives they mixed into the mass to give the product its desired properties and became well-versed in oxides and metals.

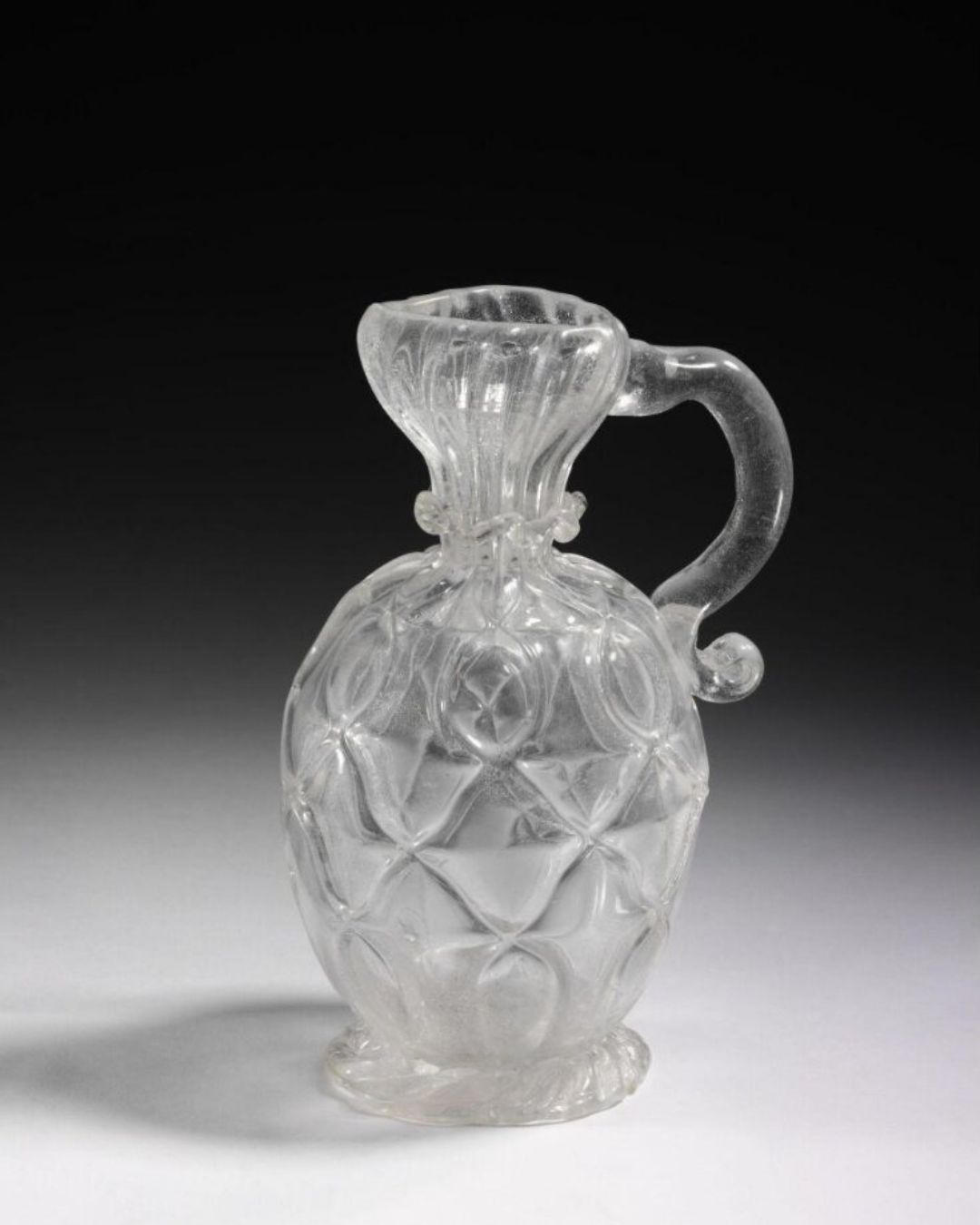

- Ravenscroft’s drinking glass. Photo: V&A

- Decanter Jug. Photo: V&A

Upon his return to England in 1666, George opened his own glass factory in London. He was undeterred by the fact that several factories in the capital were already imitating Italian glass. Ravenscroft enlisted the support of chemist colleagues, two masters whom he brought from Italy, and even members of royal blood, and for several years, he immersed himself in creating the formula for perfect crystal. Eventually, he presented the astonished public with a sample – a vessel that, unlike ordinary glass, had a special light refraction. This invention became known as “lead crystal” (Full Lead Crystal) – the added lead oxide in the right proportions was Ravenscroft’s secret ingredient, and the 24% lead content mark became a global standard.

Read also: How Diaghilev’s “Saisons Russes” influenced the European art world of the 20th century

The novelty immediately won over wealthy English buyers, who were willing to purchase “beautiful glass” instead of ordinary glass. Lead crystal products became popular in Europe, especially in Bohemia (modern-day Czech Republic), where the technology of crystal was taken to a new level. From then on, the global stage saw the battle of titans between two major glassblowing centres – Bohemian glass competing with Murano glass.

Crystal in Imperial Russia

However, soon another contender emerged for the title of the world’s best crystal – the Gus-Khrustalny factory, founded in 1756 by decree of Russian Empress Catherine the Great. Before this, Russia had no large factories of its own, and small glass workshops could not meet the high demand for glassware, mirrors, spectacles, and window panes – most of these items were purchased abroad. The first glass factory was established by merchant Akim Maltsev along the Gus River (“Goose” River) in Vladimirsky County, Moscow Province. A village, Gus-Maltsovsky, also appeared, with about 100 peasants, later growing into Gus-Khrustalny (“Crystal Goose”).

St George’s Cathedral (Museum of Crystal) in Gus-Khrustalny. Photo: vitautas, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

In 1759, Maltsev launched a second glass factory and, from small workshops, created a series of large productions. For these accomplishments, Catherine granted him nobility in 1775, and the Maltsev family gained privileges. Initially, the factory along the Gus River produced simple glasses and shot glasses. But everything changed when, in 1831, Akim’s grandson, Ivan, took over the business – an enterprising and extraordinary figure. He was the sole survivor of a diplomatic mission after Persian fanatics attacked the Russian embassy in Persia in 1829. In that massacre, Russian envoy and poet Alexander Griboyedov and his entourage were killed.

In 1835, Ivan accompanied Nicholas I on a trip to Bohemia, where he somehow persuaded Bohemian masters to sell him the secret crystal formula. He even managed to lure some of the local artisans to work at his factory. This story resembles that of George Ravenscroft, doesn’t it? Soon, the Russian manufactory was producing true lead crystal with the same 24% lead oxide that gave the product unique optical properties and flexibility. Gus crystal was no less high quality than Bohemian, yet it was significantly cheaper.

Manchester houses, revolution, and the history of the faceted glass

Visitors to Gus-Khrustalny often first notice the unusual English-style houses that remain from the city’s earlier development. Ivan Maltsev, having been on a diplomatic mission in France, was impressed by the organisation of workers’ lives at factories. Upon returning to Russia, he ordered the construction of houses for the masters in the Manchester style. Between 1860 and 1880, about 400 red-brick houses with white windows were built. Each house was divided into two halves and designed for two families, though the glassblowers were housed there temporarily, while they were needed at the factory. When a worker was no longer required, his family was evicted, with a special street for this process – Vyschvyrka (“Throw-away”). Today, only a few of these unusual houses remain, and they are still inhabited. These buildings are considered cultural heritage sites, and homeowners put much effort into keeping them in pristine condition.

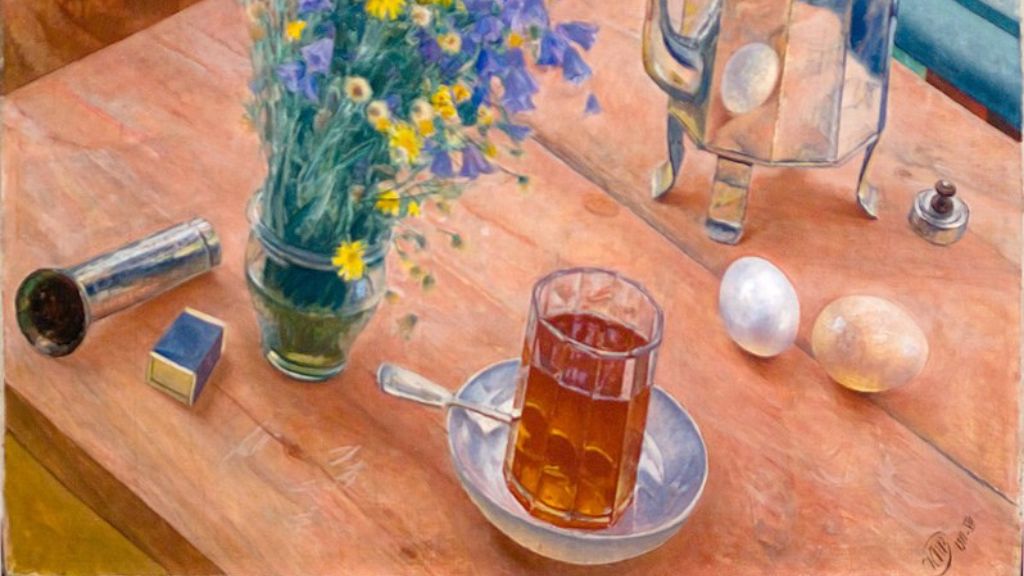

A faceted glass in a still life by Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin (1918). Photo: Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Ivan Maltsev’s descendants embraced his idea of improving the village, building an Orthodox cathedral designed by architect Leonty Benoit, pharmacies, a hospital, a school, and new red-brick factories. Gus-Maltsovsky also had a working paper- spinning mill and camel wool yarn production, but its main pride, even today, remains the glass factory. After the 1917 revolution and the rise of Soviet power, the factory faced tough times – demand for beautiful crystal declined, but there was a need for simple, reliable tableware for public dining. At that point, the idea of the faceted glass came to the rescue – a sketch was created by Soviet sculptor Vera Mukhina, the creator of the famous monument “Worker and Kolkhoz Woman,” a symbol of the indomitable spirit of the people. The design passed testing at the Leningrad factory and, after approval, was sent for mass production at the Gus factory, which then operated at full capacity. Much of the production was exported, and the factory gained fame as a laureate of numerous international exhibitions.

The village of Gus-Maltsovsky also grew – by the 1920s, its population was about 10,000, and today it exceeds 55,000. As the heartland of Russian crystal, the village was renamed Gus-Khrustalny in 1926, and in 1931, it received city status. With the collapse of Soviet power, the Gus factory fell into decline and was eventually closed, only to be revived in 2013. Today, the factory consists of several large glass processing plants where one can purchase unique crystal tableware, vases, and interior items and even take a guided tour of the production process.

Irina Lazio/Margarita Bagrova

Cover photo: William Krause on Unsplash

Read also:

Fulfilling an artist’s dream: a Van Gogh exhibition opens at the National Gallery

Somerset Maugham: writer, secret agent in Russia, and favourite of the Soviet intelligentsia

SUBSCRIBE

Receive our digest once a week with quality Russian events and articles