Ivan Bunin in London: scandalous affairs, Nobel fame and recognition in exile

Ivan Bunin was the first Russian writer to receive the Nobel Prize in Literature, and one of the few who managed to gain recognition among compatriots abroad. The second half of his life unfolded in exile in France — a journey through both wealth and poverty, through heartbreaks and passionate, often scandalous, affairs. To mark the 155th anniversary of his birth, Afisha.London revisits the twists and turns of Bunin’s personal life, his literary evenings in London, and how he became an honorary member of the P.E.N. Club.

From nobleman to impoverished editor

The future Nobel laureate was born on 22 October 1870 in the Voronezh province, into an old noble family. By then, however, the abolition of serfdom in 1861 had left the Bunin estates in decline. From the family’s former grandeur only the coat of arms remained, yet Ivan grew up with the manners of a true aristocrat. His parents raised four children and could not afford a full education for him, so part of his schooling took place at home under the guidance of his elder brother, Yuly.

Yuly was living under home arrest on the family estate for his ties with revolutionaries, and at the same time taught the young Ivan literature — encouraging his first literary experiments. That early support shaped Bunin’s self-awareness as a writer. He would become one of the first Russian authors to practise a kind of self-promotion, enthusiastically marketing his own work. Bunin mailed his poems to all his friends and acquaintances, asking them to send back glowing reviews: “Praise me, please, praise me!”

Read also: Ivan Turgenev’s Sojourn in London: a literary ambassador between the Russian Empire and the West

- 1891. Photo: http://www.bunin.org.ru/biography/, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

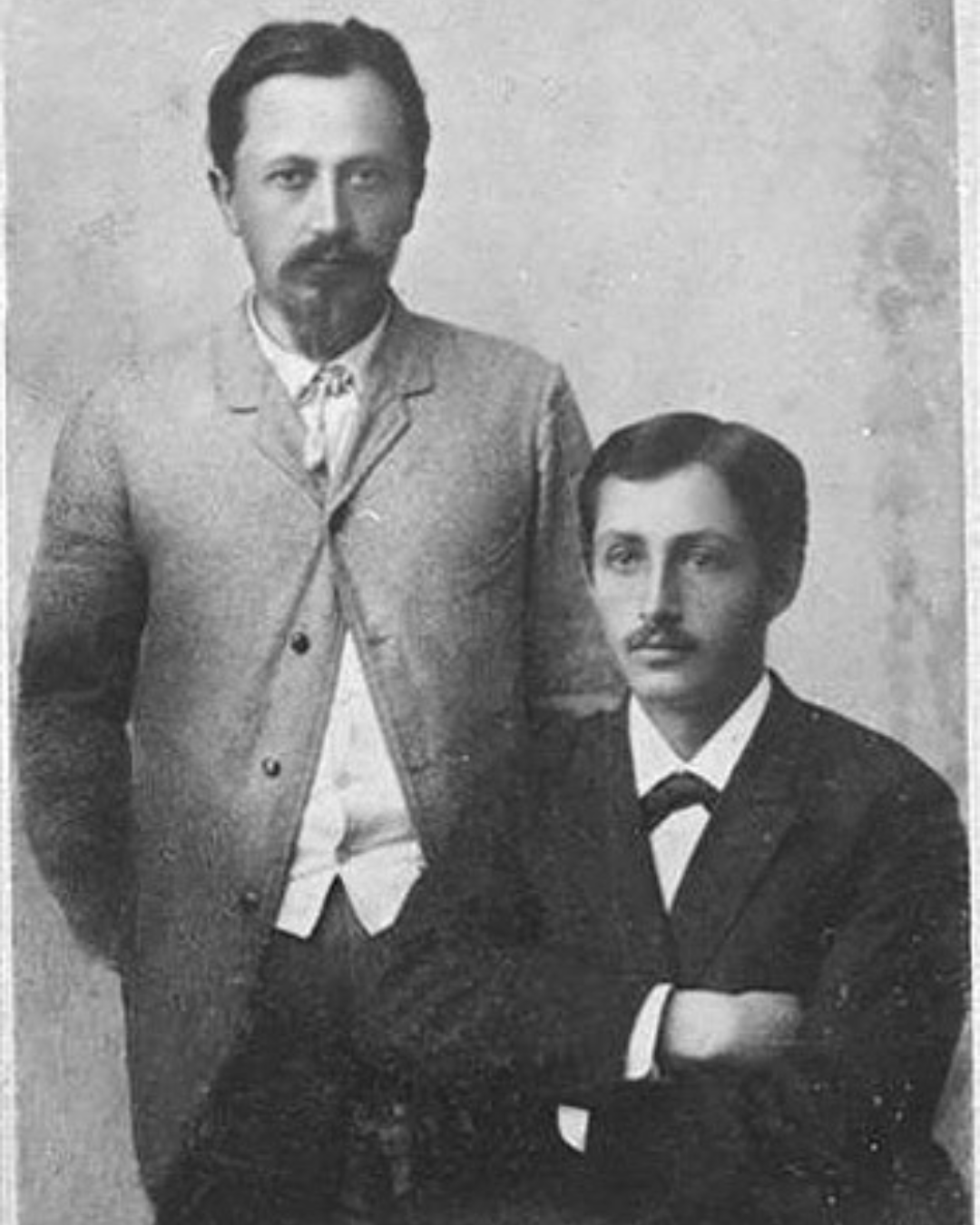

- With brother, 1890s. Photo: http://www.rodovoederevo.ru/family19565/book, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Like many creative people, Bunin had a dual nature. His family, exasperated by his temper, later nicknamed him “the literary prince.” Contemporaries recalled him as lively, witty and theatrical — yet also withdrawn, melancholic, distrustful of people, and even afraid of the dark. His writing mirrored that duality, forever circling around two poles: love and death. His life, too, would follow a winding road of brilliant ascents and painful falls.

In 1889, Bunin left his family home and began his independent life in Oryol, where he worked as an editor for the Oryol Herald. The job was exhausting and poorly paid, but it was in the newspaper’s literary supplement, in 1891, that his first collection of poems appeared. Around this time, he also experienced his first deep love. But a few years later his beloved, Varvara Pashchenko, unable to bear the poverty they lived in, left him for his friend. Bunin’s heart was broken; after a failed suicide attempt, he spent his last money on a train ticket to St Petersburg — the city where his literary fate would finally begin to take shape.

Read also: Joseph Brodsky in London: from Soviet outcast to professor at the West’s top universities

- Circa 1900. Photo: Georgi Vasilievich Trunov, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

- 1901. Photo: Maxim Petrovich Dmitriev, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

A rising career and exile in France

Bunin’s first years in the Russian capital were far from easy: he was lonely, unknown, and poor. What saved him was his talent — and persistence. He devoted every spare hour to writing poetry and prose and, in what we would now call networking, attended literary salons and made useful acquaintances. Success came quickly. His poems and stories began to appear in print, and he soon found himself the subject of admiration — including from Anna Tsakni, the daughter of his Odessa publisher. A striking and enviable match, she was the complete opposite of his first love, Varvara. Ivan married her and briefly returned to a life of comfort and luxury, but the marriage was unhappy. Beautiful yet frivolous, Anna cared little for literature or art; she preferred flirtation and the glitter of high society.

In 1900, Anna became pregnant, which only strained their relationship further. Bunin left both his wife and his publishing job. Their first and only child, Nikolai, he saw only a few times before the boy died of meningitis in 1905 — a loss that devastated him. Friends recalled that Bunin carried his son’s photograph with him for the rest of his life. Yet, even as tragedy shadowed his private world, his career soared: in 1903 he received the Pushkin Prize, marking the height of his early fame.

Invalid slider ID or alias.

It was a time when the bohemian world still revolved around writers and painters rather than film stars; salons debated Tolstoy, Chekhov, Dostoevsky and Turgenev. At one such evening in 1906, at the home of writer Boris Zaitsev, Bunin met Vera Muromtseva — the woman who would become his lifelong companion. A graduate of the Higher Women’s Courses, Vera was intelligent, graceful, and strikingly beautiful, with wide blue eyes and fluent languages. Ivan fell in love at once.

A year later, the couple embarked on their first journey together through the East and began to live as partners. They visited Maxim Gorky on Capri, travelled through Turkey, Palestine, Syria, Egypt and Ceylon. The only shadow over their happiness was that Anna refused to grant a divorce, preventing them from marrying. Only after leaving Russia were they able to legalise their union — they married in 1922, and Vera remained at his side until his death.

Read also: Somerset Maugham: writer, secret agent in Russia, and favourite of the Soviet intelligentsia

- With Vera. Photo: See page for author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

- 1937. Photo: See page for author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

In 1909 Bunin was awarded the Pushkin Prize for a second time, and in 1910 his novella The Village (buy here) brought him broad public recognition. His writing often turned to the Russian peasantry — people unaccustomed to taking responsibility for their lives — and later to the moral collapse he saw in Bolshevism.

Read also: Dostoevsky in London and his influence on the British classics

Bunin could not accept the new regime. After the 1917 Revolution, he and Vera fled to Odessa, where he wrote Cursed Days, his bitter chronicle of those turbulent times. On 24 January 1920, they boarded the French steamer Sparta bound for Paris, and later settled in Grasse, in the south of France, where a new chapter of his life began.

In exile, Bunin continued to publish poetry and wrote his major novel The Life of Arseniev, which would secure his place in literary history. In 1933 he became the first Russian writer to be awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature. He never returned to Russia, though he longed for it deeply. In May 1941, in a letter to Alexei Tolstoy, he asked that his name be put forward to Stalin for permission to return — but the Second World War had begun, and Bunin remained with his family in Grasse.

The Nobel Prize ceremony. Photo: Nobel Foundation (photographer unknown), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

A tangled love geometry and literary evenings in London

Bunin’s love affairs outside his marriage to Vera were discussed almost as widely as his books. One might think that with such a devoted and intelligent woman he would have found peace, yet at the age of fifty-six he met his muse — Galina Kuznetsova. She was thirty years his junior and had long admired the romantic image of Bunin, the celebrated émigré writer. When their feelings grew serious, Galina left her husband; Bunin, however, did not leave his wife. Instead, he brought Galina to their villa Belvedere in Grasse, introducing her to Vera as his student and secretary.

This strange arrangement — the three of them under one roof — lasted seven years. Vera convinced herself that Galina was like a daughter to her husband, and eventually accepted her presence. Both women were united by their blind devotion to the same man. The triangle collapsed in an equally unusual way: Galina fell in love with an opera singer, Margarita Stepun, and brought her to live at the villa as her “friend.” Soon another resident joined the household — writer Leonid Zurov, who was secretly in love with Vera. This web of affections would later inspire Alexei Uchitel’s 2000 film The Diary of His Wife, a portrait of Bunin’s private chaos.

Read also: Virginia Woolf and her fascination with Russian literature

But life in Grasse was not all passion and jealousy. During the Second World War, on another property — the villa Jeannette — Bunin sheltered refugees and Jews fleeing Nazi persecution, feeding them at his own expense. Remarkably, despite his fame, he had no citizenship: for all his years in France he lived under a League of Nations passport issued to stateless refugees.

Read also: Anna Wintour: how she became a fashion icon and what her exit from Vogue could mean

Despite his financial and bureaucratic difficulties, Bunin visited London several times. His first trip came in 1925 at the invitation of the P.E.N. Club, the international association of writers, poets and journalists. There he was introduced to the British literary world by the exiled Russian politician and activist Ariadna Tyrkova-Williams. In London, Bunin met Jerome K. Jerome, author of Three Men in a Boat (To Say Nothing of the Dog), and later even wrote a short piece about him titled Jerome Jerome. England stirred his imagination. He remembered the warmth of great fireplaces, the snow outside the window, and the splendid receptions the English held in his honour. Returning home, he told Vera that “the English are warmer than the French, simpler.” The feeling was mutual: in April 1925, The Times published an article by writer Stephen Graham about Bunin’s life in exile.

His next visit to London came a decade later, from 6 to 12 December 1936, when the Russian House invited him to hold a series of paid literary evenings for the émigré community. Every ticket sold out. Bunin read poems and shared memories before an audience that already knew his work well. By then, British scholars had been studying and translating his writing, and Russian-language newspapers in London regularly printed his prose and verse.

Read also: Winston Churchill: descendant of a pirate, impressionist and husband to the perfect wife

Back in 1922, Leonard and Virginia Woolf’s publishing house, The Hogarth Press, had released a collection of Bunin’s short stories — The Gentleman from San Francisco and Other Stories — translated by D. H. Lawrence and Leonard Woolf. The book was reissued repeatedly until 1951, the year Bunin received another message from London: he had been made an honorary member of the P.E.N. Club.

Those, however, were his final years. His health declined, Vera cared for him devotedly, and Galina, though no longer his lover, remained in touch, negotiating with publishers on his behalf. On 8 October 1953, Ivan Bunin died in Paris. Two months later he was buried at the Russian émigré cemetery in Sainte-Geneviève-des-Bois, beneath a monument designed by artist Alexandre Benois.

Photo: Afisha.London

He died just short of seeing his work restored to honour in his homeland. Until the mid-1950s his books were banned by Soviet censors, but in 1956 the authorities relented and allowed a five-volume collected edition to be published. Vera gradually sent Bunin’s archive back to the USSR; after her death it passed to Leonid Zurov, who later bequeathed it to Milica Green, a lecturer at the University of Edinburgh. Thanks to her, the volume In the Words of the Bunins was published — containing diary excerpts from both Ivan and Vera.

Today, Ivan Bunin remains among the most read and translated Russian authors in Europe. His works have been adapted for film many times, and his voice — refined, melancholic and fiercely human — still speaks to readers across generations and borders. You can buy all of his works in Russian in this edition.

Irina Lazio

Cover photo: Afisha.London / Midjourney

Read also:

The London Christmas Guide 2025: shows, skating and sparkling nights

The last Stroganov: how Hélène de Ludinghausen revived a lost Russian legacy

Lydia Delectorskaya: the Russian émigrée who transformed Henri Matisse’s life

SUBSCRIBE

Receive our digest once a week with quality Russian events and articles