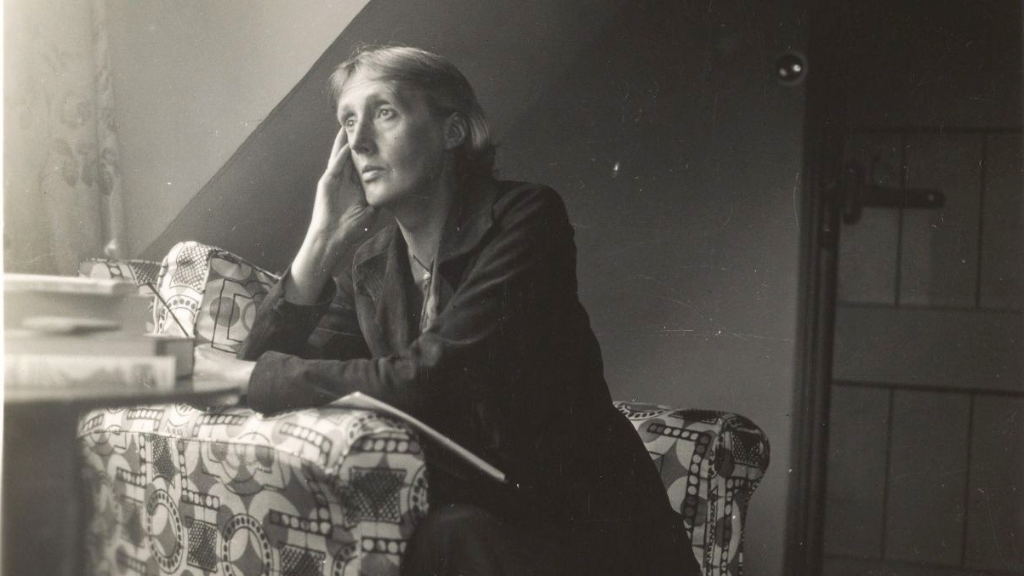

Virginia Woolf and her fascination with Russian literature

Virginia Woolf is known as the leading figure in modernist literature in the first half of the 20th century. At one time, the writer was not spared by a wave of British Russophilia: she was a fan of authors from Russia, and the characters on the pages of her works read Russian novels. Afisha.London magazine tells how Russian literature shaped Woolf’s original artistic thinking, and how Dostoevsky, Chekhov, Tolstoy and Turgenev opened up new literary horizons for her.

Russian literature played an important role in the development of Virginia Woolf’s writing talent, and the influence of Russian classics is felt in her novels and stories. Being not only a writer but also a literary critic, Woolf reviewed the works of authors from Russia and analysed them in her essays.

In her library, Woolf collected the works of many Russian writers, including Gogol, Goncharov, Gorky and others. However, the works of Dostoevsky, Chekhov, Tolstoy and Turgenev helped Woolf find her style, showing her narrative possibilities different from British literature. In their works, the writer found a new concept of the novel, which deeply and voluminously reflected the life of a person and the peculiarities of his consciousness. Subsequently, she borrowed these modes of artistic expression, unusual for European prose, for her literary experiments.

As Daria Protopopova emphasizes in her book Virginia Woolf in Context, Woolf found contemporary works of 19th-century Russian novelists, discovering in them a new kind of realism. The Russian classics concentrated on feelings and emotions, and revealed the secrets of human nature, while the British focused on “social behaviour, manners, superficial details”. The writer noted in Russian authors a specific way of describing the human soul, attention to the inner world of characters. According to Protopopova, for Woolf their focus on the soul stemmed from their interest in human psychology.

- Colour photo: Jasongart

- Colour photo: Navarrete

In the article Virginia Woolf and Russian Literature, Tatyana Krasavchenko explains that for Woolf, sincerity in the works of Russian classics was important, which distinguished them from the background of Victorian novels. This was the essential difference between Russian and British cultures: the writer contrasted depth, compassion, spirituality, and sadness with the desire of British authors to “disguise, cover up or embellish what suffers and suffers in us”. And the “gloom” of Russian literature Woolf put against the “natural delight” of the British, manifested in “humour and comedy”.

After reading Crime and Punishment, Woolf considered Dostoevsky “the greatest of writers”. It was from him that she learned the techniques of internal monologue, stream of consciousness and twin characters.

Chekhov attracted the writer with a concise reproduction of a palette of emotions, problems of mutual understanding and loneliness. She was close to his approach to both comic and melancholic depiction of everyday life.

Read more: Antonio Canova’s ‘Three Graces’: Crafting a Neoclassical Masterpiece

Tolstoy was also considered by Woolf to be “the greatest of novelists” along with his epic War and Peace. She was also impressed by the novel Anna Karenina for the depth of the characters.

In Turgenev’s works, the writer noted observation, accuracy and objectivity, the ability to combine a masterful depiction of natural scenes with a description of the thoughts and feelings of the characters, and a convincing depiction of Russian life.

Due to her ignorance of the language, Woolf’s perception of Russian literature depended largely on translators. Under the guidance of Samuel Koteliansky, the writer began to learn Russian and help him with translations into English of Chekhov, Dostoevsky and Tolstoy, Bunin, Gorky and other authors.

Photo: Afisha.London / Midjourney

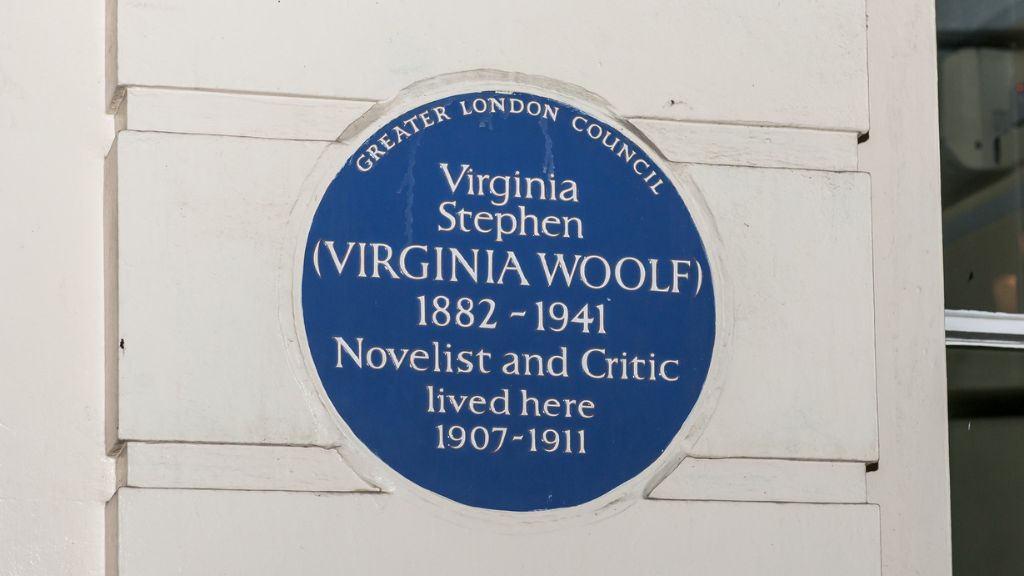

There are many places in London connected with the life and work of Virginia Woolf, where memorial plaques are installed.

- 22 Hyde Park Gate

This is Virginia Woolf’s childhood home where she lived with her family. It is a stone’s throw from the Royal Albert Hall, on the street where the upper middle class lived. Thus, Virginia’s father was a well-known historian and publicist, her mother worked as a model, and her sister became an artist. Here you will see three plaques dedicated to the writer, her sister and father.

- 46 Gordon Square

After the death of her father, who died shortly after Woolf’s mother, the future writer and her loved ones sold the family home and moved. The Bloomsbury Group, an elite group of English writers, artists, and intellectuals, was born here. Later in her diary, Virginia would write: “…Moving from Kensington to Bloomsbury, we crossed a whole gulf between a respectable existence in a lethargic dream and a life more difficult, even perhaps cruel, but real.”

Harvard University library, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

- 29 Fitzroy Square

After her sister’s marriage, Woolf moved with her brother to a new location, where the Bloomsbury meetings were also held. However, the society was divided into two groups: artists gathered in Gordon Square, and the literary circle in Fitzroy Square.

- 38 Brunswick Square

Later, Woolf and her brother moved again. Here the writer met her future husband. He was a writer too.

Photo: Nick Harrison / Flickr

- Hogarth House

The Woolfs moved here a few years after their marriage. Here they decided to found the publishing house Hogarth Press. The Woolfs published each other’s books, the works of other Bloomsbury members, and works by foreign authors such as Maxim Gorky.

- 52 Tavistock Square

The very building that Woolf lived in was destroyed during the Blitz. However, the plaque reminds us that once there was a house of a British writer. The area inspired many Virginia passages from Mrs Dalloway and To the Lighthouse. Here the writer observed the life of the city.

Cover photo: Afisha.London / Midjourney

Read more:

How Diaghilev’s “Saisons Russes” influenced the European art world of the 20th century

Composer Pyotr Tchaikovsky in London: impressions, recognition and success

Flappers — emancipated women of the 20s in the West and in Russia

SUBSCRIBE

Receive our digest once a week with quality Russian events and articles