The love and hate story of artist Pablo Picasso and Ballets Russes dancer Olga Khokhlova

Pablo Picasso – the greatest artist of the 20th century and a notorious womaniser. Over his lifetime, he encountered many women, but one of his key muses was his first wife, Olga Khokhlova. A ballerina from Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, Olga captivated Picasso with her elegant modesty. However, their life together, which propelled both into high society, ended tragically. Afisha.London magazines explores how Picasso immortalised his life with Olga on canvas, turning their story into a public legacy and a cherished piece of his artistic heritage.

Steps to success

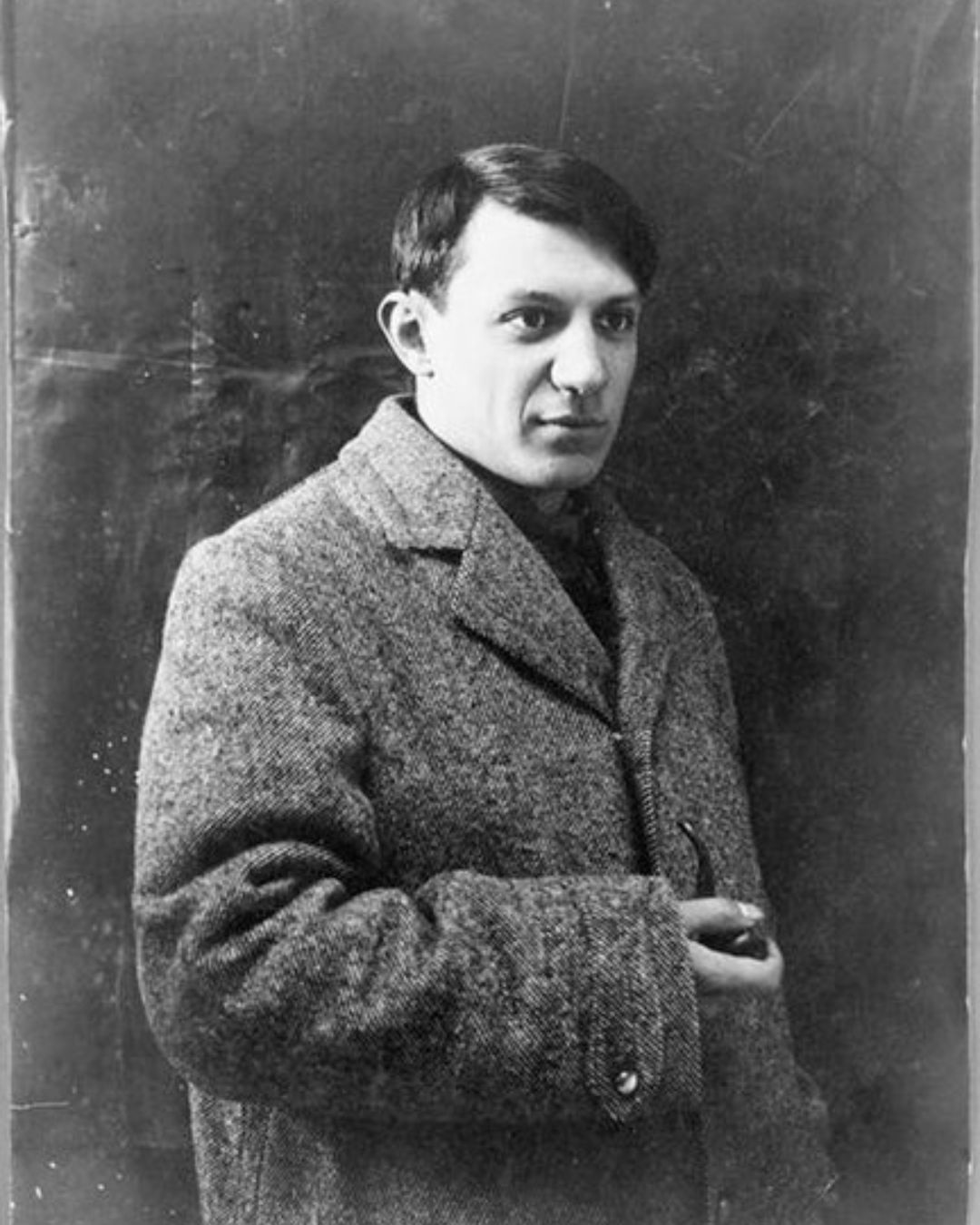

The father of Cubism was born in Andalusia, a region bursting with true Spanish spirit – passionate flamenco, siestas, gazpacho, and a love for bullfighting. Picasso was born on 25 October 1881 in the picturesque village of Málaga, surrounded by the towering fortresses of Gibralfaro and the Alcazaba. Nowadays, Málaga is filled with contemporary art museums, but back then, it was only his father, an art teacher, who inspired young Pablo to pick up a brush early. A family move to northern Spain broadened his horizons, and Picasso dreamed of attending the La Lonja School of Fine Arts in Barcelona, where he was accepted at 14, defying age restrictions. It was there he signed his work not with his father’s surname, Ruiz, but his mother’s, which would become famous – Picasso.

In 1897, Pablo enrolled in the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Madrid, though he was more interested in studying the works of Italian and Flemish masters at the Prado Museum. In 1900, Picasso found himself in Paris at the World’s Fair, where he encountered Impressionism. In Paris, during his time on bohemian Montmartre, Picasso entered his “Rose Period,” marked by vibrant and joyful tones. By 1907, alongside Georges Braque, he founded Cubism, inspired by African ritual masks seen at the Paris Ethnographic Museum, which transformed humans into idols. From then on, Picasso became obsessed with breaking natural, rounded forms into sharp, geometric blocks. Cubism dominated his work until 1916, when he met Olga Khokhlova, a ballerina from Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes.

Read also: Ivan Bunin in London: scandalous affairs, Nobel fame and recognition in exile

- Pablo Picasso, 1908. Photo: AnonymousUnknown author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

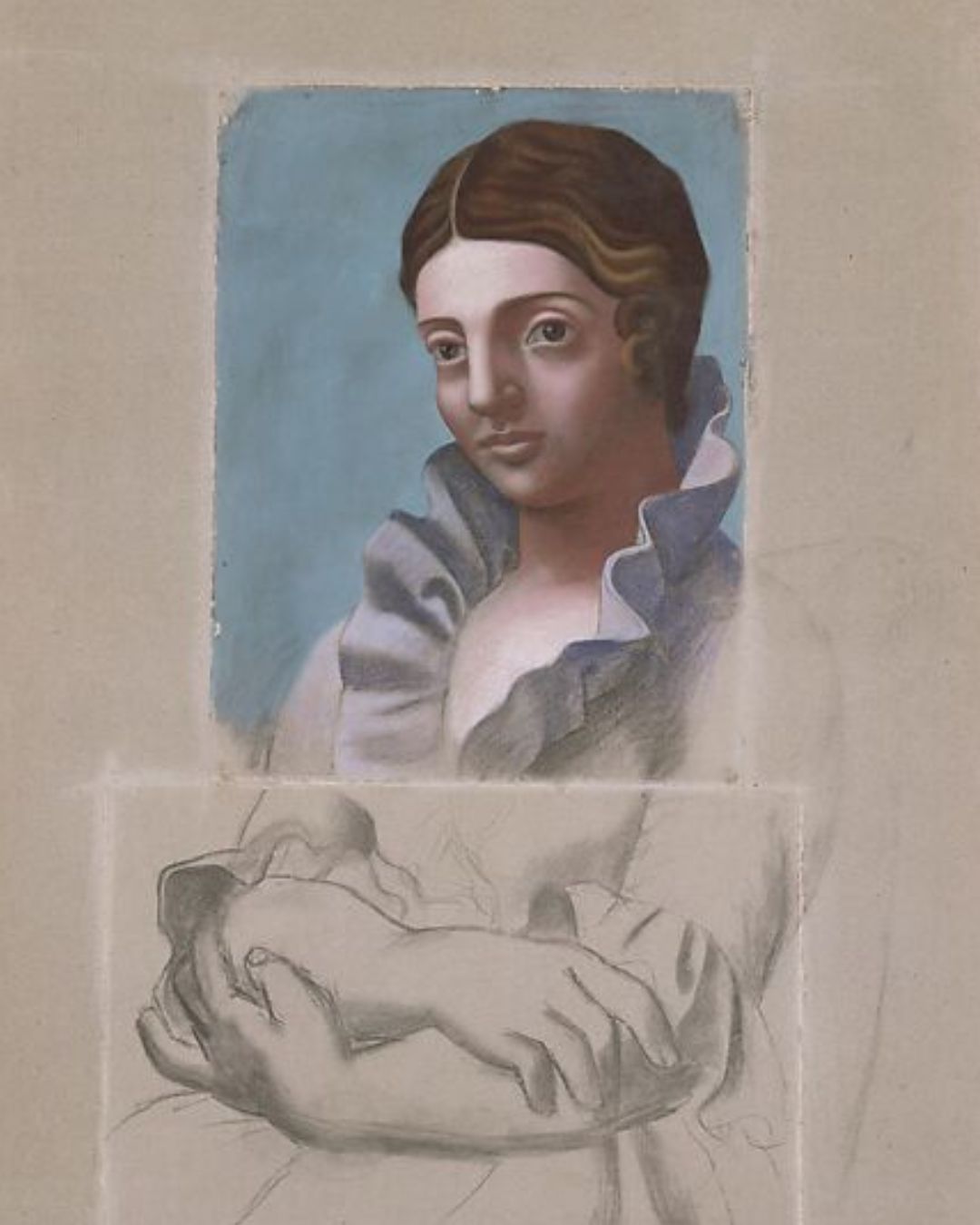

- Olga Khokhlova on a ballet postcard. Photo: Bibliothèque nationale de France, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes and meeting Olga

In 1916, Picasso was introduced to Sergei Diaghilev, whose Ballets Russes were already popular across Europe. Diaghilev needed a talented designer for his extravagant productions. Picasso’s distinctive Cubist style influenced the costumes he created for the ballet “Parade,” which premiered on 18 May 1917 at Paris’s Théâtre du Châtelet and ended in a scandal. The audience hurled insults at the production team, but this did not stop Diaghilev and Picasso from staging five more productions together. During rehearsals for “Parade,” Picasso met Olga, a hard-working, talented, statuesque, and stunning woman. Diaghilev warned Picasso that “you must marry Russian girls,” and Picasso took this as a cue. He pursued the reserved Olga with intense passion. Initially, she was overwhelmed by his advances, but her modesty and virtue only fuelled Picasso’s desire to win her over. Determined, Picasso proposed to Olga, and here we must pause to reflect on the woman who captured his fiery heart.

Read also: Emigration of the Romanovs to Great Britain: the story of Grand Duchess Xenia

Olga Khokhlova was born on 17 June 1891 in Nizhyn town, then part of the Russian Empire, now Ukraine. She came from a noble family; her father, Stepan Khokhlov, was a colonel in the Imperial Russian Army, which allowed her to study ballet in a private school in St. Petersburg and travel across Europe. In 1915, Olga joined Diaghilev’s troupe, though she never became a prima ballerina. Fate had a different role for her – to be a muse and later a tormentor for one of the most extraordinary artists of the 20th century. After meeting Picasso, things progressed quickly. Soon, Pablo was introducing his beloved to his mother in Barcelona, where he painted “Olga Khokhlova in a Mantilla.” By the summer of 1918, the couple were married in a ceremony at the Russian Orthodox Cathedral of Alexander Nevsky in Paris, a key place for Russian émigrés after the 1917 Revolution.

Read also: Elizabeth II and Russia: a visit to Moscow, a box for Yeltsin and the impressions of eyewitnesses

- Olga Khokhlova in Picasso’s Montrouge studio, spring 1918. Photo: AnonymousUnknown author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

- ‘Olga in an armchair’, Pablo Picasso, 1918. Photo: Margarita Bagrova

This marked the end of Olga’s ballet career. Diaghilev’s troupe went on tour to South America, but Olga, having injured her leg just before the wedding, walked down the aisle with a cane. She would keep her ballet tutu and pointe shoes in a trunk for the rest of her life, as a reminder of her carefree youth. Madame Ruiz-Picasso spent her honeymoon in Biarritz recovering from her injury, thoughtful and melancholic – a mood Picasso captured in his sketches of her.

Back in Paris, life took a livelier turn. The newlyweds moved into a luxurious apartment on Rue La Boétie, which Olga, with her commanding presence, divided into two halves. The living space was elegantly decorated and impeccably maintained for hosting guests, while Picasso’s studio was a chaotic mess of creativity. Under Olga’s influence, Picasso transformed from a bohemian artist into a bourgeois socialite, welcomed into the highest circles of Parisian society. Many of Picasso’s friends disapproved, finding Olga cold and haughty. Yet, in Picasso’s eyes, she was perfect. She wanted her face to be recognisable in his paintings, and Picasso began painting in a neoclassical style. These years are often referred to by art experts as Picasso’s “Olga period.”

Read also:

- Portrait of Olga. Photo: © RMN – Gérard Blot 1921

- ‘Portrait of Ogla Picasso’, 1923. Photo: © Fundació Museu Picasso, Barcelona

From muse to nightmare

In 1919, Pablo and Olga arrived in London, where Picasso was invited by Diaghilev to work on the set designs and costumes for the Spanish-themed ballet The Three-Cornered Hat. The ballet was a success at the Paris Opera and London’s Alhambra Theatre, which now stands as the Odeon Luxe Leicester Square cinema. On 4 February 1921, the couple welcomed their son, Paul (Paulo), an event that brought immense joy to both, especially to the 40-year-old Picasso, who found renewed inspiration. He painted Olga and their son in rounded, monumental forms, embarking on a new artistic direction – monumentalism. However, their blissful life on the French Riviera was overshadowed by letters from troubled Russia. Olga’s mother wrote, informing her that her father and brothers had joined the White Army, another brother had died, and her mother and sister Nina were on the brink of poverty.

Olga, distressed, often hid her tearful eyes from Picasso, seeking ways to send parcels and money back to Russia, mourning the family she would never see again. Picasso supported his wife as best he could – when one of Olga’s brothers fled to Serbia, Picasso sent one of his paintings to the wife of a local Serbian general, ensuring his brother-in-law would be offered a position. Unfortunately, this period coincided with Picasso’s growing disenchantment with his once-beloved wife. He grew tired of their bourgeois lifestyle, longing for chaos and the bohemian life once more – something Olga desperately tried to prevent, succumbing to jealousy. Their quarrels and conflicts were starkly reflected in Picasso’s art, as his previously elegant depictions of Olga transformed into surreal portrayals of her as a monster. Distorted limbs and grotesque expressions in works like “Large Nude in a Red Armchair” and “Woman with a Fur Collar. Olga” illustrate Picasso’s view of his wife. With the arrival of Picasso’s new muse and lover, Marie-Thérèse Walter, their life together devolved into a nightmare, or as modern psychologists might say – an abusive relationship.

- ‘Grand Nu au fauteuil rouge’, 1929. Photo: © RMN – Grand Palais

- ‘Portrait Of Marie-Therese Walter’, 1937. Photo: © Fundació Museu Picasso, Barcelona

For six years, Olga endured the presence of her husband’s mistress right under her nose. Picasso rented an apartment for Marie-Thérèse just across the street on Rue La Boétie and even took her on family holidays. Eventually, the new muse bore him a daughter. (Editor’s note: The daughter of Spanish artist Pablo Picasso and Marie-Thérèse Walter, art historian Maya Ruiz-Picasso, passed away in 2022 at the age of 87.) Unable to bear it any longer, Olga filed for divorce, only to face a major obstacle: the prenuptial agreement stipulated that she was entitled to half of Picasso’s property, including his artworks, upon divorce. Unwilling to part with his masterpieces, Picasso refused to finalise the separation. Defeated, Olga retreated to the south of France with their son, finding herself isolated as their mutual friends sided with Picasso, finally “free” after years of what they saw as Olga’s forced domesticity imposed on the artist.

Read also: The history of crystal: how an English invention thrived in Russia

Later, their son Paul returned to his father, who employed him as his personal chauffeur – though the salary came with constant humiliation. Another of Picasso’s lovers, writer and artist Françoise Gilot, who later had a daughter with him, the renowned designer Paloma Picasso, wrote in her diaries that the artist treated Paul cruelly, publicly calling him a fool.

The Many Faces of Picasso

In her final years, Olga began to lose her sanity, with only her granddaughter Marina by her side. Marina later published a memoir in 2002 titled “Grandfather”, recounting her childhood memories and portraying Picasso as a tyrant, an egotist, and a cruel genius. Olga died of cancer on 11 February 1955 in Cannes, remaining Picasso’s legal wife until her death. Picasso, who detested any display of illness or weakness, refused to visit her during her illness and did not attend her funeral. He outlived his first wife by 18 years, during which time he had countless lovers and married once more. Picasso died on 8 April 1973 at his villa Notre-Dame-de-Vie in Provence and was buried in the courtyard of his château Vauvenargues.

Invalid slider ID or alias.

However, passing judgment on geniuses remains a challenge for society. Picasso’s legacy is immense, his influence on people unparalleled. In a 2009 poll by “The Times”, with 1.4 million readers, Picasso was voted the greatest artist of the last century. Even those unfamiliar with his paintings know his iconic symbol – the white dove with an olive branch. It is said that Picasso created the “Dove of Peace”, one of the most recognisable symbols of peace, for the World Congress, inspired by memories of the gentle and meek Olga Khokhlova, as she once was in her youth.

Irina Lazio / Margarita Bagrova

Cover photo: collage Afisha.London / picassolive.ru, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons / Argentina. Revista Vea y Lea, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons / Midjourney

Read also:

Rudolf Nureyev: from emigrant to ballet luminary

Felix Yusupov and Princess Irina of Russia: love, riches and emigration

Amedeo Modigliani and Anna Akhmatova: the enigmatic nude romance

SUBSCRIBE

Receive our digest once a week with quality Russian events and articles