Felix Yusupov and Princess Irina of Russia: love, riches and emigration

Prince Felix Yusupov and Princess Irina Alexandrovna of Russia went down in history as a brilliant example of remarkable mutual understanding, loyalty and love. The niece of Emperor Nicholas II and the heir to the richest family of the Russian Empire went through serious trials together: confrontations with venerable figures and public opinion, a conspiracy against Rasputin, a revolution and a difficult emigration to Europe. Their story is strikingly similar to an adventure novel — together they have shared half a century of incredible ups and downs. Afisha.London magazine recalls the main milestones in the life of the Yusupovs, their time in exile and the immutable presence of London in their destiny.

The Yusupov dynasty is considered one of the richest and most influential families of the Russian Empire. The luxury in which they lived could compete with the wealth of the emperor himself: their possessions spanned rare jewellery, paintings by Rembrandt, Lorrain and Boucher, 57 palaces and private land all over the country, but their family estates in Saint Petersburg and Crimea played the most important roles in the lives of Felix and Irina.

Prince Yusupov’s early years

Refined, resourceful and handsome, Felix Feliksovich Yusupov — a true descendant of a noble house and the only heir to a multimillion-dollar fortune — was born on March 23, 1887 in an atmosphere of universal recognition and prosperity. A darling of fate and a tireless artist, Felix adored pranks and masquerades, dressed in women’s clothes and easily fooled officers and gentlemen, appearing in public in frivolous lush boas and sequins and generating a whirlpool of gossip around his already bright persona. The epoch favoured Yusupov, at the beginning of the 20th century Saint Petersburg was full of costume balls, for which the prince gladly chose exquisite outfits.

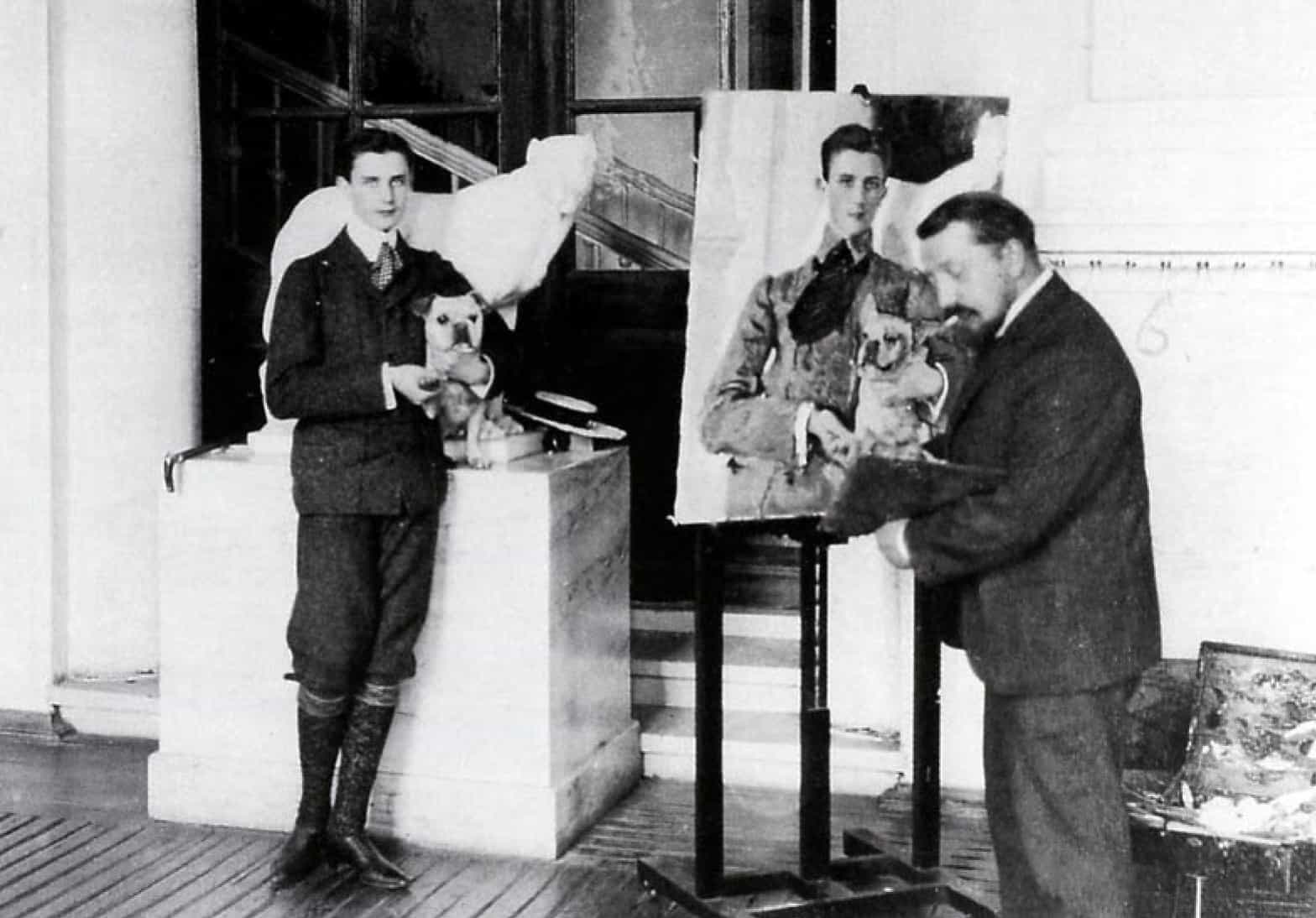

- Felix Yusupov in a dress suit (1902-1903). Photo: Museum-Estate Arkhangelskoye

- Portrait of Felix Yusupov by Valentin Serov (1903). Photo: Serow, Walentin Alexandrowitsch, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

But everything changed in 1908: Felix’s elder brother and an accomplice in all his dashing tricks, Nikolai, was killed in a duel, which was a terrible trial for the whole family. The love and care of the grieving mother Zinaida Nikolayevna instantly fell upon her only remaining son, who himself was growing restless. In his memoirs, the prince would later write about how, while in complete confusion, he was engaged in charity work and wandered through the slums, helping the poor and the sick, and how when looking around the vast family lands, he thought about the future with utter melancholy.

Felix Yusupov posing for Valentin Serov with his French bulldog Clown (1903). Photo: name lost, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Young Felix Yusupov in Oxford

Felix was saved by the advice to study at Oxford, so he immediately went to England to explore this possibility. In London, the prince stayed at the now destroyed Carlton Hotel and then went straight to the vice-chancellor of the University of Oxford to see the famous institution first-hand and book rooms for study. The city fascinated him, he later recalled: “Numerous colleges — all former monasteries with high walls and luxurious parks. From century to century, replacing each other, generations of students maintain the spirit of eternal youth within these ancient walls. I would leave Oxford in tears, if I did not know that I was going to return very soon”. In 1909, prince Yusupov arrived in England as a student and studied at the University of Oxford until 1912.

Student life helped the prince to respire; he gladly got acquainted with young people of different nationalities from all over the world. People attracted the prince much more than studies. During his first year, he founded the Russian Society of the University of Oxford, which still exists today — this organisation supports Russian students and spreads information about Russian culture. After spending a year in student rooms, the prince began renting a flat in the city and regained his former glory as a playboy: piano concerts and parties were a constant presence at his place, while Mary the parrot heart-rendingly screamed in the corridor and Punch the bulldog ran around.

- Velvet caftan made of gold brocade with embroidery, gilded and silver threads and diamonds. Made to order for Felix Yusupov in Saint Petersburg for a costume ball at the Royal Albert Hall in 1912. Photo: Hermitage Fine Art

- Multi-coloured leather boots that were made together with the caftan. Photo: Hermitage Fine Art

Felix began attending balls and masquerades in Paris and London. After the costume ball at the Royal Albert Hall, where the prince made a splash with a spectacular 16th-century brocade caftan, he attracted the attention of all London newspapers. At the Royal Opera House, Yusupov enjoyed performances of Sergei Diaghilev’s ballet troupe and knew many artists personally, while his friendship with the famous “Russian swan” Anna Pavlova bore a confidential manner — of two people, who understand each other perfectly. However, the main treasure awaited Felix back in Russia. On one of Felix’s visits to his homeland, the prince met his future wife and was captivated by her calmness and gentle, slightly tragic beauty.

Felix Yusupov and Prince Christopher of Greece and Denmark at the ball at the Royal Albert Hall. Photo: © National Portrait Gallery

The beginning of an extraordinary romance that lasted half a century

As if to counterbalance Felix’s stormy temperament, Irina Romanova was an extremely withdrawn and silent girl, although her noble birth and widely recognised beauty bestowed her with numerous privileges in the aristocratic society. Historians believe that the girl’s shyness came from the difficult relationship between her parents: Grand Duchess Xenia Alexandrovna, daughter of Alexander III, and Grand Duke Alexander Mikhailovich, grandson of Nicholas I.

Irina was born on July 3, 1895 and became their first and only daughter: later the princely couple also had six sons. Long before the birth of their last son, the couple started quarrelling and switched to a scandalous lifestyle, not even trying to hide their extramarital affairs. Irina was disgusted by this, which caused her delicate and sensitive nature to suffer. The princess wanted to emphasise her spiritual nobility and to become for someone a safe haven in this world of human passions and vices. Such a person she saw in Felix, with whom she fell in love.

- The Wedding Day. Photo: http://www.pinterest.com/pin/102949541453949392/, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

- Felix and Irina Yusupov (1914). Photo: Boissonnas et Eggler, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Yusupov courted her beautifully, he conducted himself with restraint and nobleness, realising that he was claiming the hand of a princess from the imperial family. The young prince had to fight for the girl’s love: Irina’s grandmother, Empress Maria Feodorovna, was against their engagement; moreover, Yusupov’s reputation did not speak in his favour. However, despite all the obstacles, in 1913 the young couple got engaged and on February 22, 1914, in the chapel of the Anichkov Palace in Saint Petersburg, they celebrated a magnificent wedding with a thousand guests. The newly-weds were blessed by Nicholas II and Maria Feodorovna, while the luxurious Yusupov Palace on the Moika River was already waiting for them: a whole wing with fine antique furniture, gold dishes and vases strewn with precious stones was prepared for the happy couple. Alas, the Yusupovs’ wedding was the last festive event for the Romanov family.

Forced flight to Europe

In March 1915, the couple had a daughter, Irina, and, despite the events of World War I, they managed to lead a measured life and raise their baby, while the prince received military education. Family wealth allowed them to watch the war from the sidelines and help their country financially — the Yusupovs maintained two hospitals and a sanatorium at their Crimean estate Koreiz. The real danger came from the mysterious healer Grigori Rasputin, under whose hypnotic influence fell both the imperial family and their subjects: public policy was under threat.

It is still not known for certain whether a military order was issued to get rid of Rasputin or the conspirators united following their own initiative. Be that as it may, the prince took an active part in the murder of the mystic. Irina was deeply worried about what her husband had done — her boundless love was faced with condemnation, but she survived and even got stronger. However, Rasputin’s end was fatal for the princely couple. After the abdication of Nicholas II, Russia ceased to be a comfortable home for the Yusupovs, and the 1917 Revolution forced them, together with their relatives, to move to the Ai-Todor estate in Crimea, where, under threat of arrest, the whole family spent an excruciating year and a half.

On March 13, 1919, the Yusupovs left Crimea with a heavy heart on the British warship HMS Marlborough overloaded with compatriots, which headed for Malta, where the princes exchanged family jewels for new passports and visas. In London, the Yusupovs found refuge in Felix’s bachelor flat in Knightsbridge, which the couple had already visited during their romantic honeymoon trip. Last time, the couple was greeted with pompous social receptions, but now their arrival in Europe was accompanied by a stream of refugees from Russia, who hurried to exchange everything that was left of their former wealth for the opportunity to start a new life.

The Yusupovs at the Tea House in Eagle Bay (Barskaya Polyana). See page for author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons (colour correction Afisha.London)

New life in emigration

With the characteristic for him enthusiasm, the prince actively took care of his fellow emigrants: thanks to his many friends in England and the chairman of the Red Cross, Pavel Ignatiev, he managed to organise employment workshops, as well as to provide new arrivals with clothing, help and practical advice. Irina was helping women, while Felix provided for men and sought financial subsidies to support a good cause. Nevertheless, the Yusupovs were in a more advantageous position than their compatriots — the smart prince was able to bring enough jewellery and two paintings by Rembrandt from Russia. With the money raised, it was decided to purchase a mansion in the Bois de Boulogne in Paris and to settle in France. In addition, another surprise awaited the Yusupovs in Paris — an expensive car that had been parked in the garage for a long time in case of their arrival in Europe.

- Irina Yusupova in an Irfe dress and a family tiara. Photo: irfe.com

- Irina Yusupova in an Irfe dress. Photo: @maisonirfe

Meanwhile, something incredible was happening in France. The world’s fashion capital was filled with noble gentlemen and beautiful ladies, who once shone at luxurious balls at the court of the Russian emperor, but now were forced to count every penny and learn new skills in order to survive. The Yusupovs were also running out of funds. Then Irina and Felix decided to take advantage of their aesthetic taste and brilliant education, creating a fashion house Irfe (Irina / Felix). In 1924, the first dresses were cut and sewn on the floor of an improvised atelier in a tiny Parisian flat, where Russian countesses and princes worked as designers, dressmakers and models. Subsequently, designers around the world would repeatedly return to the refined luxury of outfits in the style of Yusupovs.

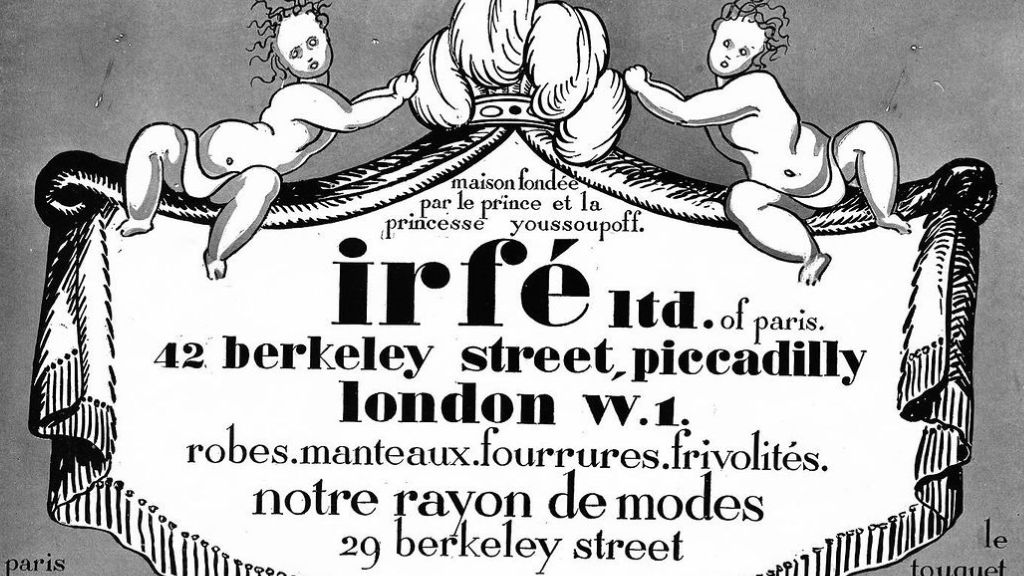

The rise of the Irfe fashion house was incredibly fast. After the debut show at the Ritz, Parisian magazines exploded with rave reviews: the original designs and refined style of the outfits perfectly matched the fashion of the 1920s, and the aristocratic models drove the audience crazy with their grace and sophistication. On the wave of their success, the couple opened three branches of Irfe — in London on Berkeley Street, in Berlin and in Le Touquet. The Yusupov’s fashion house lasted until bankruptcy in 1931, when the laconic and comfortable clothing from Coco Chanel came into fashion.

IRFE’s advert in Vogue magazine. Photo: @maisonirfe

The legacy of the Yusupovs

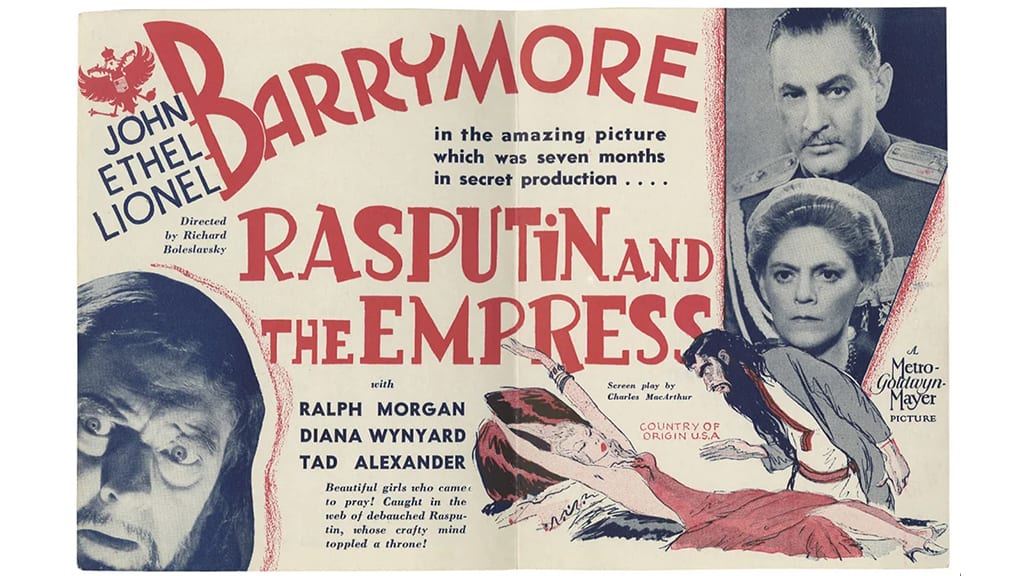

Aid to emigrants and the secular lifestyle that the Yusupovs led — in particular, the prince, who retained a love for events and restaurants — assumed high costs, and after the closure of Irfe, the family’s finances were under threat. However, luck favoured the Yusupovs once again. In 1934, Felix cleverly sued the American company Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer for a huge sum for slandering Irina in the film Rasputin and the Empress. After this incident, film companies always include the “all persons fictitious” disclaimer in the credits. Furthermore, the prince enjoyed good income from publishing two manuscripts: The End of Rasputin and Memoirs.

Poster for “Rasputin and the Empress” (1932). Photo: IMBD

Yusupov no longer attempted to establish his own business. With a position in society and a livelihood, he and Irina collected art and supported young talents. In 1967, the couple adopted the Mexican Victor Contreras, who later became a famous sculptor in the United States and Europe, and their daughter Irina by that time was married to Count Sheremetev and lived in Rome. The Yusupovs met their end in a modest flat in Paris — the prince died in 1967, while Irina outlived her beloved husband by three years. The colossal influence that the princely couple had on the course of world history is relevant to this day.

The elegant Yusupov Palace in St. Petersburg cherishes the secrets of the past and serves as a museum and a theatre. In 2020, Max Mara created a resort collection “Reason and Romanticism”, inspired by the luxurious aesthetics of the Yusupov outfits, while at auctions in Paris secret documents, correspondence, photographs and paintings from the personal archives of the couple keep resurfacing. The world is still haunted by the secrets of this great dynasty.

Irina Lazio

Cover photo: Boissonnas et Eggler, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Read more:

Justine Waddell on launching Klassiki: a streaming platform for Russian cinema

SUBSCRIBE

Receive our digest once a week with quality Russian events and articles