Joanna Stingray, American friend of Tsoi and Grebenshchikov: “I left Russia thinking I would never return”

American Joanna Stingray is a legend of the Russian musical underground. In the mid-1980s, they talked about her in the Leningrad rock club no less than about the rising rock stars — Aquarium, Kino, Alisa and others. She was under surveillance by the KGB and the FBI at the same time, both organisations suspecting her of espionage. She was simply obsessed with Russian rock, which she then was able to popularise in the USA by releasing the Red Wave album. On the eve of Viktor Tsoi’s 60th birthday, Margarita Bagrova, editor-in-chief of Afisha.London magazine, met Joanna in London and found out why she fell in love with Russia so much.

Joanna Stingray is an American singer and music producer. She was a key figure in popularising Soviet and Russian rock music and culture in the West in the 1980s & 1990s. She lived in Russia from 1984 to 1996, now she lives in Los Angeles.

— Your father made a documentary film about communism and told you never to go behind the Iron Curtain, to stay away from the terrible USSR. How did it happen that you, a young girl, did exactly the opposite?

— Whenever a parent tells the child year after year warnings of something not to do, it always stays in the back of his or her head. And when I called my sister, who was going to school in London, and I wanted to visit her, she said: “By the way I’m going on a trip to Russia for a week.” A light bulb went on and I said without thinking: “I want to go.” I wanted to go just because I had in the back of my mind since I was so little that the Soviet Union was an evil empire and a scary, awful place. I was 23.

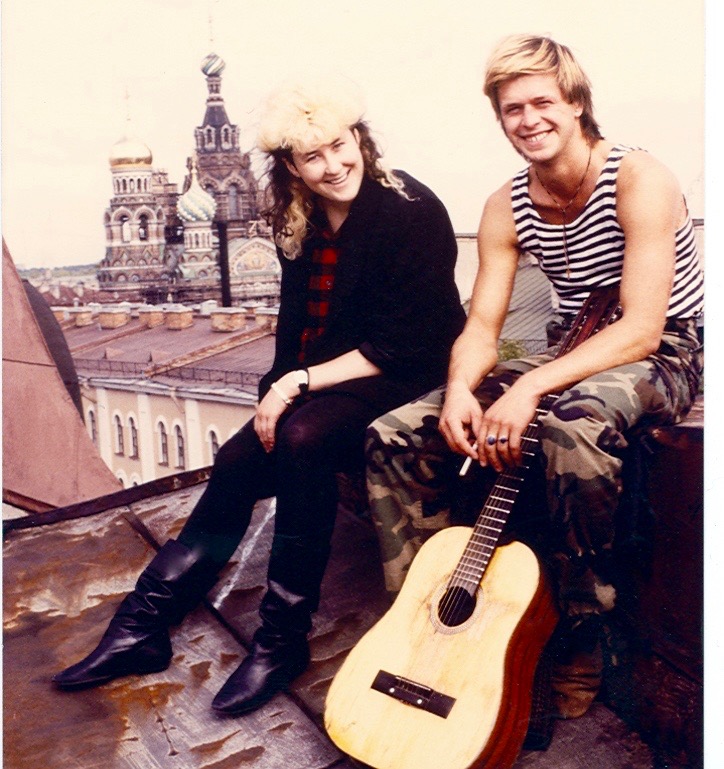

Rock Club concert, Tsoi, Stingray, Sologub & BG

— It was probably difficult to get into the USSR in those years.

— Yeah, it wasn’t easy in the 1980s to get to Russia. For the first couple of years, I went back and forth to Russia for only a week at a time. In the mid-1980s, it was impossible to stay longer — it was allowed only one week of stay. These were special tours from INTOURIST, you should stay with the guide, not stray from the bus.

Stingray with Red Wave Bands

— Do you remember your impressions from the first trips? Did you experience the quality of life of the Russian people, the lack of food, and public transport, or did you travel like a tourist, using a taxi and staying in a hotel?

— When I landed in Moscow in April 1984, I had the feeling that I was in a 1950s movie. Everything seemed old, scary, and very similar to my father’s warnings. During the bus tours, I was looking out the window: the sky was grey, and the atmosphere felt grey. The people wore dark grey, dark blue, and black clothes. They did not look happy and I thought I would never come back here again.

Of course, there were things that I liked. First of all, I was amazed by the lack of advertising, because in America advertising was everywhere. I liked the huge communist murals for their shape and boldness, the massive Red Square, and the impressive St Basil’s Cathedral.

- Joanna & Boris, 1984

- Kuryokhin & Stingray, 1985

— Indeed, in April in Moscow and Petersburg it’s still quite dark and miserable.

— Yeah, that’s why when I left Moscow to go to St Petersburg for the rest of the week, I thought: “I will never come back here, my father was right.”

— How did you meet Boris on your trip then?

— Before going to the first USSR trip, I was given by one friend the landline of “some Russian” Boris. One evening I escaped from tour and met with Boris. That changed my perception of USSR and Russians. After meeting Boris, who introduced other people to me, I quickly realised that the Russians behaved completely differently on the streets and behind closed doors. I was just amazed at how similar they are to Americans, and how they communicate. From the moment I first entered Vsevolod Gakkel’s apartment, where I met Boris, I realised how gracious they are when they bring tea and cookies, that they are great hosts and warm people. At that moment everything I thought about Russia changed and I thought about returning to this vibrant, crazy country with these incredible people. Even if it was just a week every three months, it was worth it.

Yuri & Joanna

— You were young and travelling that often to Russia was quite expensive. In addition, you always were bringing presents to all your friends – fancy clothes and music equipment. What did you do to cover these costs?

— I started work as a travel agent after the first time I went to Russia, because then I was motivated to just figure out how to get back. It was the perfect job because I made some money, but I also could figure out where there were cheap airplanes to get to London from where tours to Russia started. I did spend some of my own money on the things I bought – but because I wasn’t making very much money, I was going to this place in Los Angeles, Melrose Street, that had all these punk stores where I could buy rubber bands and punk bracelets for a dollar or so. What was amazing is that because the Russians didn’t have access to the stuff, I could bring them so much that cost very little money but to them was so valuable, you know. Then I approached the equipment stores, I became friends with the manager, and he let me buy musical equipment with something like a 50% discount. That certainly helped. When we got some money from our record company, from the Red Wave record, we would take that money and use it. If I sold any of the artwork that they gave me as gifts, I would go and buy them equipment. Overall it was any way I could find money from my work, from selling the art, from the album sales. Any, any time I got money, I would go and buy them things because they needed it.

Follow us on Twitter for news about Russian life and culture

— Let’s go back to your wedding with Yuri Kasparyan. I saw some photos; I think it was on a higher level than the average Soviet wedding. Do you remember your wedding dress?

— Yes, my mother mentioned that I should get a wedding dress. And I said, I don’t wear dresses and I certainly don’t wear white. She offered to hire someone to design a dress, especially for me, and I liked this idea. We designed this dress, which now I look back and to me it’s so crazy. The outfit was traditionally white, but the design itself looked a little futuristic. I remember the first time Victor and Boris and all of my friends saw me in the dress, their eyes just got so wide! They could not believe I was in a white dress with heels. I felt so uncomfortable wearing this dress and heels that in the middle of the party after the ceremony I changed into my black pants and black flak boots.

Marianna Tsoi, Joanna, Yuri & Victor Tsoi

— You secretly transported cassettes with the music of your friends and the lyrics of their songs to America. That was something extraordinary for a young woman!

— You know, when you’re young, you are really fearless. I certainly felt nervous sometimes doing these things. And I was so passionate and determined to show Russian music to Americans. I was sure that they would feel the same as I did when they learned about those cool people like us that I met in Russia. I was blinded by the goal of showing that Russia is not only my father’s film and what was on the news in our childhood.

I hid the cassettes and lyrics in my big winter boots or leather jacket with lots of zippers all over, and there was a big zipper on the back. Customs in those days, of course, could check everything, but they didn’t have X-ray machines. As long as they didn’t pat me down, I could get away with carrying things out, which was scary.

I was also lucky that through Boris and Sergei, I became friends with some people from the Swedish, French and US embassies in Leningrad because they all loved underground rockers and came to their concerts. So, there was a kind of connection with the Western world. And I was lucky enough that the Swedish consulate helped get a couple of tapes out through their diplomatic post.

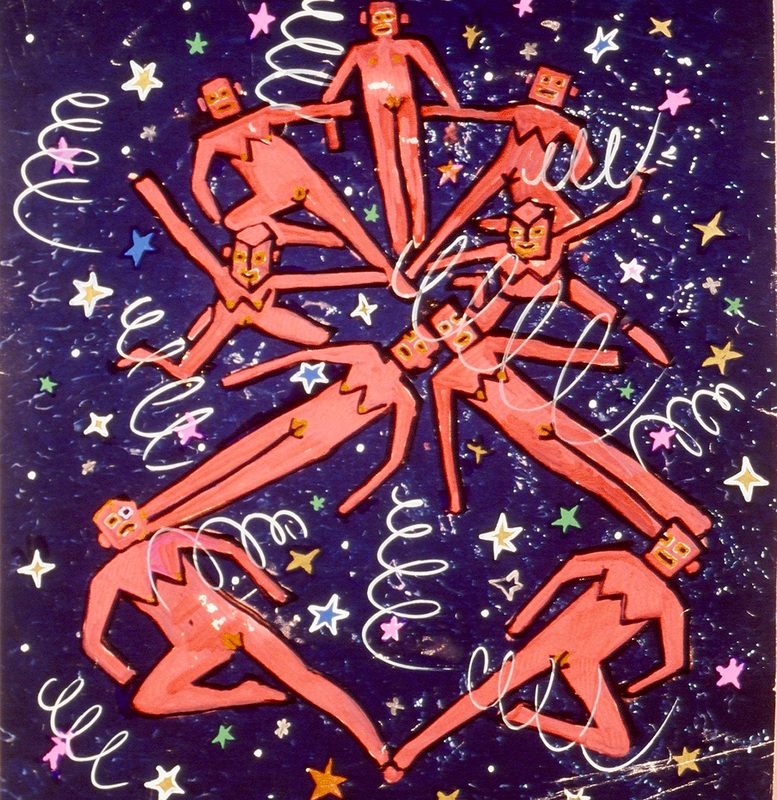

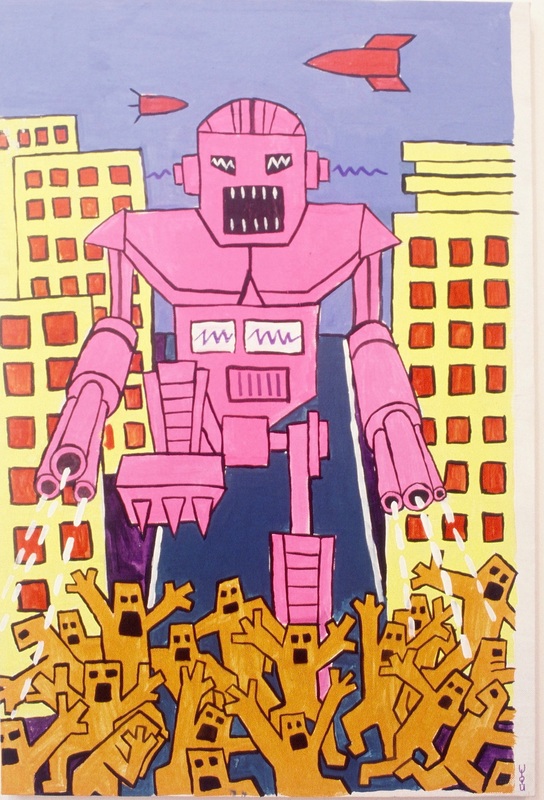

Tsoi, drawing on plastic

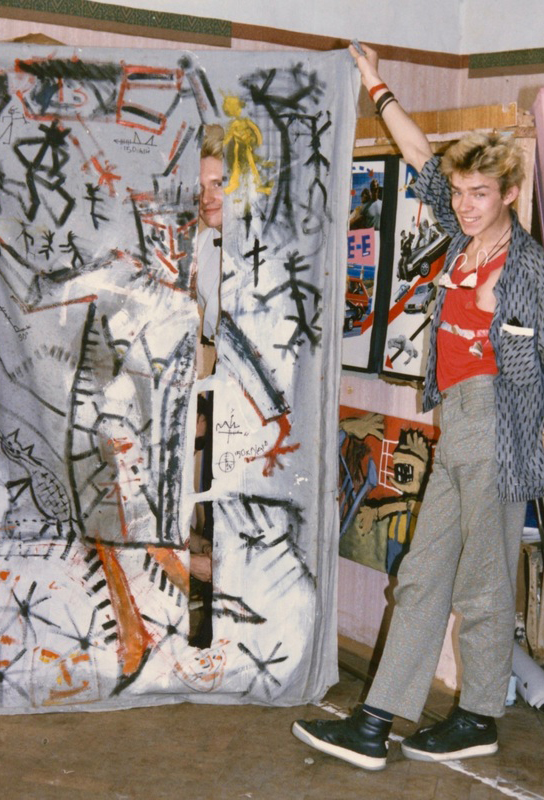

— As far as I know, in addition to songs, you opened contemporary Russian art to the West, which you also brought through customs.

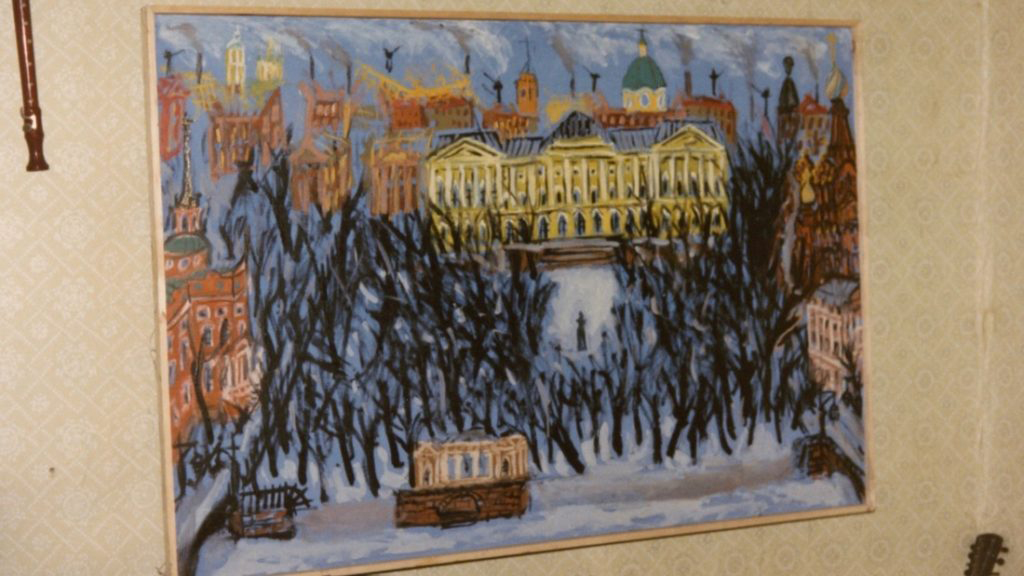

— It was really unbelievable because a lot of the artists were also musicians. However, they did not have the proper materials, so there were few acrylic-on-canvas paintings. Artists improvised and painted on wooden boards, shower curtains, and fabric. It was so fascinating! In many ways, it was just luck that I managed to leave Russia with all this art. The customs officers did not understand contemporary art, so when they would look at the paintings, I would say: “Oh, my friend’s kid did that!” I ended up taking out something like 200 pieces over a couple of years.

Then customs suddenly closed, and it was very difficult to bring out any art at all without paperwork. I was bringing artists the one thing they needed, which was equipment, and then they would give me their art mostly as a thank you.

Timur Novikov, Russian State Museum

— And what happened to these paintings?

— I ended up having about three shows. The first show was at a big gallery in Los Angeles where I raised money for Greenpeace. At the second art show, I sold some art to buy artists more supplies and to pay for all the frames. So, unfortunately, I have very little of the art left and I am not happy about that. At the museum, at the University of Rutgers in New Jersey, there was some man that was very into collecting underground Russian rock, and he bought 30–40 pieces from me. And then my parents’ friends that were art collectors had it. There’s a piece at MOCA, the famous contemporary museum in Los Angeles.

- Tsoi

- Timur Novikov, self portrait

— After reading your book, I think you are such a brave woman. Did you realize that having only an American passport was still quite risky in the USSR and you could get into trouble?

— Back then, Americans thought that an American passport was like a golden ticket. And I also naively thought that it would always protect me. I think that stupidity allowed me to be fearless and do all these things. But when I met all these guys, in the back of my head I have a fear that what if my visa is declined? I can’t be here. My whole life was in Russia, the air I breathe was Leningrad, and being with them was the blood that kept my heart pumping. And of course, eventually, I did have my visa declined. But again, about the passport. It was such a typical American mistake that we somehow think this passport protects you in other places and it does not. If you do something wrong in whatever country, they have a right to arrest you.

- Afrika with his art

- Tsoi

— Exactly! But you had meetings with the KGB and also in your country with the FBI. Does it mean that you were being watched?

— Yes. And when I was contacted by the FBI and when I heard from Boris that the KGB was asking about me, that raised my stress levels! It was obvious they both thought I was a spy. And, again, I was just nervous that my visa was going to be declined.

— Would you allow your young daughter to take the same risk? After all, it was dangerous, especially with no instant communication like a telephone.

— If she wanted to go on a trip to North Korea right now, I would say no way. No way. And now I feel for my mother. She was so nervous about what I was doing. And when she knew the FBI was talking to me, she said, you must be in danger. You’ve got to stop.

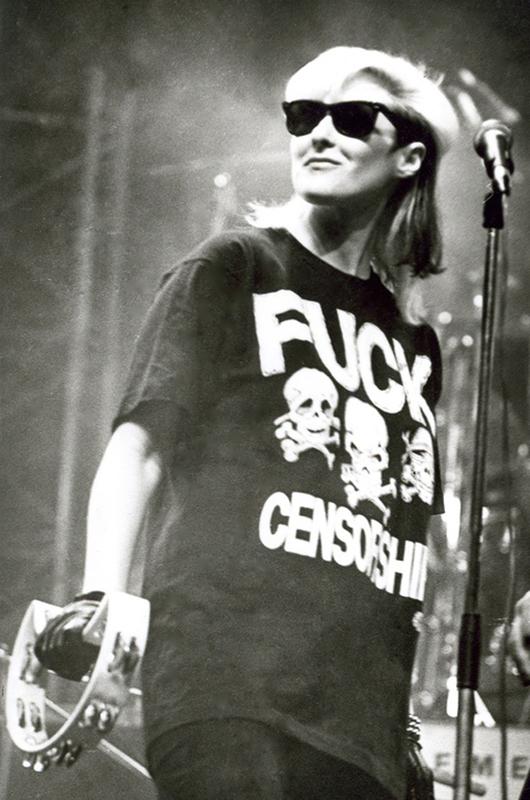

- Joanna Stingray

- Joanna Stingray

— Through all these trips to Russia and years with Russians did you finally manage to understand this mysterious Russian soul? How would you describe it?

— Russians are deeply connected with Mother Earth; how many hundreds of years have their relatives and everybody been connected to Russia. It made me understand that in America, we’re mostly all immigrants. My grandparents on my father’s side came from a little town outside of Kyiv. My mother’s side grandparents came from Prussia. That was part of Russia and Poland. We only have a generation or two here, so we’re not as tied.

— Stingray is not your real name. How did it happen that you changed it?

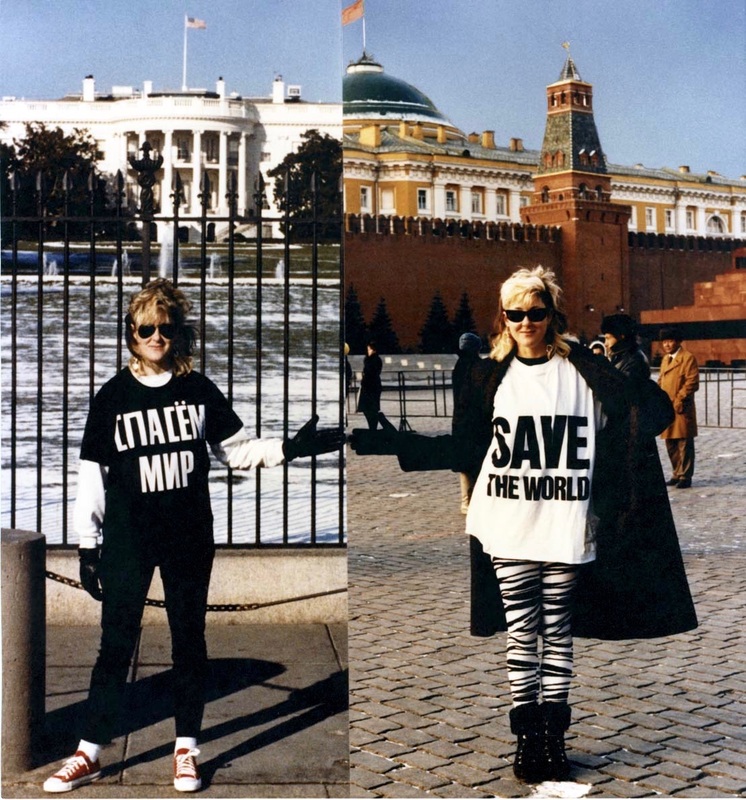

— When Boris and I planned to do the Red Wave album, we decided that we needed code names. And one time I was driving with my boyfriend, he was a collector of Stingray Corvette cars. I was telling him about this album I was going to do, and that I needed a code name. And when I looked at my feet were on the dashboard of a car and between them was written Stingray. That’s how I got my codename for the album.

Very quickly the rockers and their fans started calling me Stingray. And when I was going to get married to Yuri, my visa was declined, and I could not return to Russia. There was a way to get to Leningrad through Finland, where only a passport number was required for the trip. So, in 1987, I officially changed my name to Stingray, getting a new passport with a new passport number.

Come Together video shoot, Joanna & Boris

— How did you feel when you lived in Russia?

— My 12 years in Russia from 1984 to 1996 felt like living through three different systems. First was under Communism and as a Western person, there were so many things that were so exciting to see. But I always knew I could leave. I didn’t have to stay and live under communism, but it was really incredible. And then came the period of glasnost, which was the best period because the Russian people were so happy because little had changed, but they felt like they could say what they wanted. The third period is my least favourite. It is the 90s, capitalism, but it was the first time I could actually make money in Russia with a TV program that I had. So, I stayed and had my own career in the 90s in Russia, but it was a crazy time.

And in 1996 I was pregnant with my daughter from my second husband, Sasha Vasiliev, and I came to Russia for a month when I was six months pregnant to edit my TV program. I was planning to give birth in Los Angeles and then go back and live in Russia. And one night before leaving Russia, when I was in my apartment on Prospekt Lenina in Moscow on the seventh floor, I went out onto the balcony and looked at the city and this country that had such an impact on my life. Tomorrow I would get on a plane and never come back. I returned once in 2004 when my daughter was eight and then did not come back until 2018. And now Russia is back in my life.

- Stingray Moscow mid 90’s

- Stingray

— What made you come back to Russia again?

— When I left in 1996, I hardly ever had any more connections with my Russian friends. From time to time Sasha Lipnitsky contacted me to say that someone had died. When I heard it was a long-distance call, I would start shaking, thinking, “Oh no, who else is dead?” I had no contact with my friends for many years. And then about five or six years ago I thought, I wonder if my Russian friends are on Facebook. That’s how I found Boris.

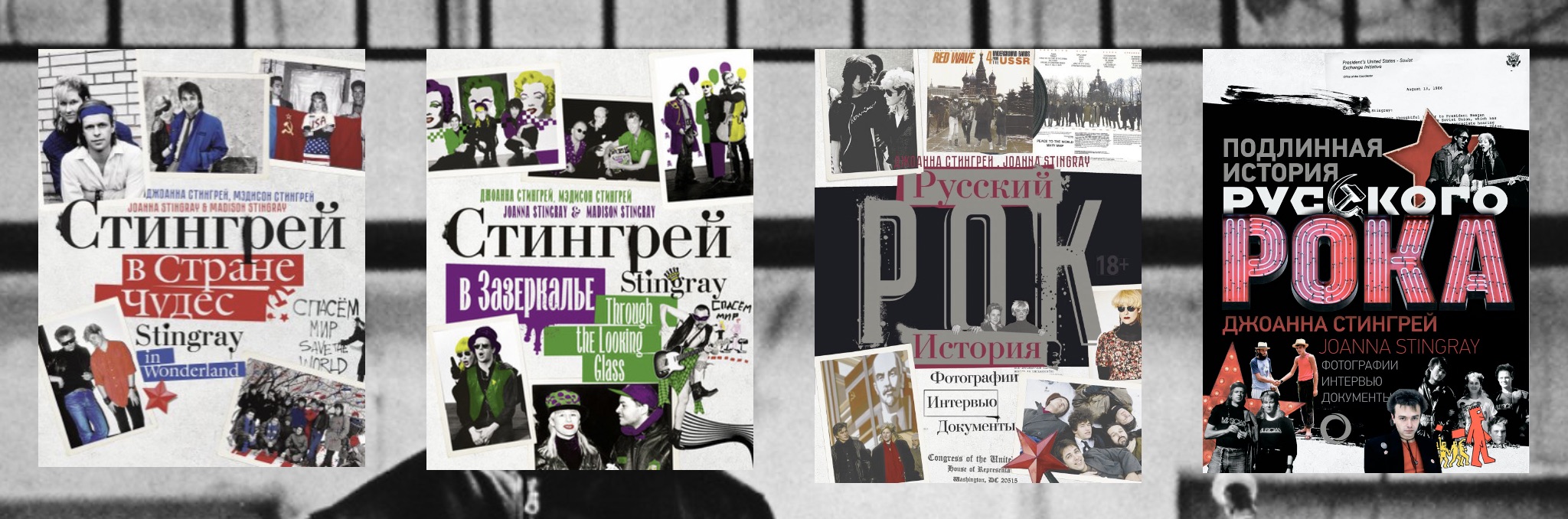

Then I decided that I wanted to get rid of boxes with thousands of photos in my house. I got the idea to scan these photos and make a website. I assumed the Russians would love it, but I had no idea to the extent that the Russians flipped out over this website that showed the lives of all their heroes in the eighties. I started to realize the nostalgia that the Russians had for the Leningrad rock and roll. I had always wanted to write a book and so I started to write my memoir. So, I wrote two books. Then I started to do the photo books with documents and the interviews that the guys did. It has become a big part of my life again (To learn more about Joanna Stingray’s books, visit her official website. — Editor’s note).

Books by Joanna Stingray

— What did you think about Russia when you returned after a long break? What got better and what got worse?

— I returned to Russia eight years later, in 2004. It was the 20th anniversary of my first coming to Russia and I was completely shocked at how Moscow looked because it had all these casinos with flashing lights. As I said earlier, I loved that there was no advertising all over the place. St Petersburg at that time had more of the vibe that it always had. Then I came back to St Petersburg in 2018 and Moscow in 2019, and I was really amazed. Moscow seemed like London or New York, a big, huge, vibrant, bustling city with wonderful five-star hotels, tons of incredible restaurants, people on the streets, all dressed really stylish, going to work. It felt like things had changed so much since 1984. And St Petersburg also had nice restaurants and nice hotels. But for some reason, St Petersburg always has something of its original charm. You know, I have always had some very strong connection to St Petersburg. Every time I step onto the earth there, I feel like I’m home.

Shot from the film “Summer”. Photo: Alexey Fokin

— Have you watched the film Summer by Serebrennikov? Did the producers of the project contact you as a witness to those events?

— They didn’t call me about the film, although I emailed the producer and asked if I could see a copy because Russian journalists kept asking me about the film and I hadn’t seen it.

As a Western person, just watching a film as if I didn’t know anything, I thought it was a very good artistic film. I thought about the value of the production, the screenwriter, and directing. There are a lot of artistic things in the film that I liked, they made me feel like I was there again. Though there were scenes, like the one on the beach, that never happened.

Shot from the film “Summer”

Knowing the people in the film, I had two issues with it. First, I know when a movie is based on a true story, it gets exaggerated and some things change, but there’s a line that shouldn’t be crossed. In this film, Mike Naumenko finds Victor and brings him to a rock club. But Boris brought him, this is really part of Boris’ legacy. Boris is such an important part of history and the father of Russian rock and roll, and taking that away from him was not really good.

Secondly, I was so close with Tsoi, I knew who he was, how he moved and with what energy. It was very hard for me to watch the actor because he didn’t have it. Victor had such a strong face, a very narrow face with a dramatic jawline that is very much the essence of Victor. The actor didn’t have that and didn’t have that energy.

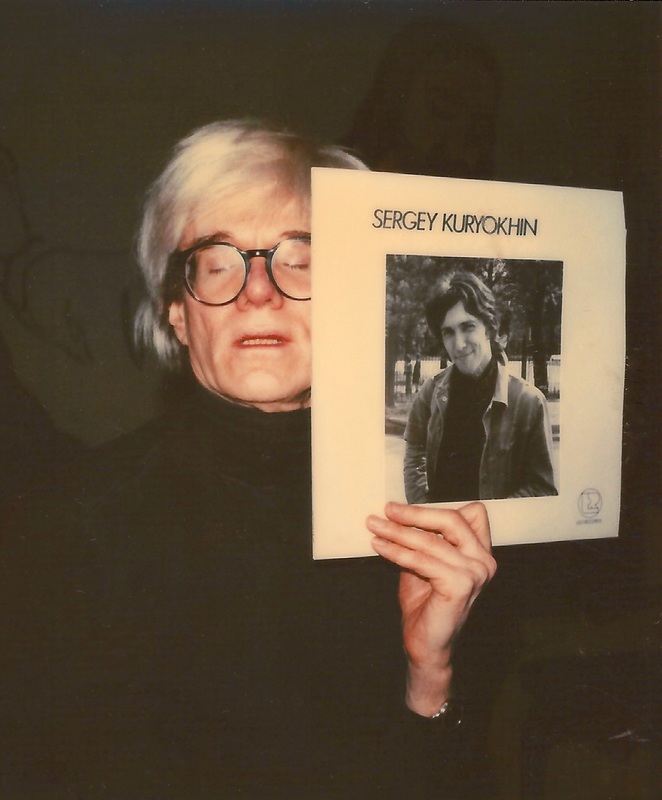

- Andy Warhol holding Kuryokhin album 80’s New York

- Joanna Stingray & Margarita Bagrova

— The peak of rock’s popularity came in the 1980s, in the 90s it gradually changed due to publicity, freedom, and the commercialisation of everything. In our hard days, in the days of this war, do you think a new underground world of Russian music could emerge?

— Most musicians say that rock and roll in America in the 80s was dull because of multimillion-dollar contracts. When you have that money, the big house and the Rolls Royce, you want to keep that lifestyle. So, you almost self-censor stuff to keep your bosses happy. And it sort of takes the edge off. The best rock and roll in history is when it’s honest and pure. It’s very hard to make honest and pure rock when you’re making a ton of money from it. And Boris even said he was afraid of that when everything opened up and they could tour and do many things. I think that’s what happened in Russia, which is why the 90s were not so exciting.

It seems to me that during the last four or five years people feel that they are not happy enough, there’s not enough fulfilment. They want something. And it seems that this is the perfect time for some new pure rock music to come up somewhere. It doesn’t have to be Russia, London, or Los Angeles, somewhere in the world. But it would be nice if it could happen in Russia again.

Cover photo: Maria Inkova

Read more:

From Britain to Russia: a tradition of “Stonehenges” across Europe

Composer Pyotr Tchaikovsky in London: impressions, recognition and success

How Diaghilev’s “Saisons Russes” influenced the European art world of the 20th century

SUBSCRIBE

Receive our digest once a week with quality Russian events and articles