From Britain to Russia: a tradition of “Stonehenges” across Europe

The latest exhibition of the British Museum The world of Stonehenge masterly uncovers an enigmatic and complex period of prehistoric Britain, full of mysteries and archaeological puzzles. These impressive megaliths, raised around the same time as the pyramids of ancient Egypt, and their artefacts are an object of interest for many generations of scholars and enthusiasts. However, what if Stonehenge is just one piece of a big picture? Afisha.London magazine and columnist Julia Mints talk about recent archaeological finds both in Europe and in Russia, which point to the various connections of the ancient world, which, probably, like the modern world, has always been global.

In the last decades archaeologists have found a lot of evidence of similar henges from Britain to Russia dated in the Neolithic period and Bronze Age. Although researchers believe that these monuments were raised by people of different cultures, they find intriguing parallels in the principles of building and resembling elements of rituals and beliefs. The phenomena might be explained by the similarities in the development of human ideas about nature, along with migration and the exchange of goods inside and outside cultural ranges.

Cultural and trade exchange

Cultural and trade interconnections of the prehistoric world and waves of migrations have been an important concern in archaeology for more than thirty years, resulting in the World Systems Theory also known as the Core-Periphery Theory. According to this concept, more advanced parts of the world had “technologies”, whereas others provided resources such as metal, jadeite stones and others. People traveled to exchange goods and to acquire raw materials that were not locally available. The confirmation of this cultural and trade exchange can be found in artefacts across Europe.

Follow us on Twitter for news about Russian life and culture

According to Dr. Lisa Brown from Oxford University, an examination of 2000 Neolithic axes from England and Wales showed that 27% were greenstone volcanic tuff from Great Langdale in Cumbria. Rituals of exchange at special locations, accompanied by ceremonies of feasting, weddings and burials, would have been memorable occasions.

Nowadays we have ample evidence of travelling far away outside a single cultural area. In 2002 the grave of a man dated around 2300 BC was discovered three miles from Stonehenge, at Amesbury. It contained the complete skeleton of a man and the richest array of items ever found from this period, including around 100 objects such as copper knives, small gold hair tresses, sandstone wristguards, flint arrowheads and Bell Beaker pots. The most intriguing thing is that the tests on the enamel found on the Amesbury Archer’s teeth revealed that he grew up in the Alps region. The Archer is thus an example of people from abroad bringing the Bell Beaker culture from the continent to Britain. He was more than just a trader. He came with the vital skills of metal working, and that would have given him great status in the eyes of local people, they would have thought him a magician. He would have been one of the first people in Britain to have been able to work gold. According to Wessex Archaeology, it is also possible that the Archer was linked closely to Stonehenge: he may have had a hand in planning the monument, or at helping erect the stones; perhaps he was drawn to the area because the stones had just been erected. He would certainly have been well acquainted with the site, and other monuments nearby such as Woodhenge, Durrington Walls and Avebury.

The remains of an Amesbury Archer. Photo: Richard Avery

The most spectacular find of recent years, the Nebra Sky Disk also brings information to this area. This artifact excavated in Germany in 1999 is treated as an ancient astronomical instrument. The tin in the bronze of the disc is argued to be Cornish, and most recently discovered, the gold fits best with a Cornish signature as well, suggesting that connections implied by other means had a reality in material transfers (Anthony Harding, 2013).

Another fascinating discovery is the origin of the Jade Axe (4000 – 2000 BC) found in Canterbury in 1901. Only a few years ago, in 2003, the precise origin of the stone it was made from was identified. The former director of the British museum Neil MacGregor writes: “Archaeologists Pierre and Anne-Marie Pétrequin spent twelve hard years surveying and exploring the mountain ranges of the Italian Alps and the northern Apennines. Finally they found the prehistoric jade quarries in Italy that the axe comes from”. But it was not a single axe. Many of the Alpine jadeite axeheads were dispersed across Britain, Ireland, and the Channel Islands.

Nebra Sky Disk. Photo: DPA

Trade exchange and migration were probably the result of cultural interconnections reflected in the comparable rituals and structures strongly linked to the building of megalithic circular monuments. It is well known that the tradition of stone circles and henges was widely spread in Britain. There about 1000 stone circles across the country, while the number of henges is approximately 120, dated between 5000 and 2500 BC. Alongside the British Isles, more than a hundred earthworks enclosures were found in Central Europe, including Germany, Austria, Czech Republic, Slovakia, as well as the adjacent parts of Hungary and Poland. The best known and oldest of these circular enclosures is the Goseck circle, constructed 4900 BC in Germany.

Read more: Elizabeth Taylor: love affair with jewellery

Intriguingly, from Poland there are no signs of circular monuments to West Siberia. However, over recent decades in this part of the continent archaeologists have found several fascinating ritual landscapes including the most famous one — Savín. This site dates to early 3rd millennium BC, which is more ancient than Stonehenge and Woodhenge in Britain.

Jade Axe. Photo: © The Trustees of the British Museum

Savín

a ritual circular landscape in Russia, the first half of 3000 – 2500 BC

The ritual land of Savín was found accidentally in 1982 in the Kurgan region, Russia thanks to agricultural works in the area. A local man discovered a few objects in the field and brought them to the historical museum. The study of these items demonstrated that the area might be a historical landscape.

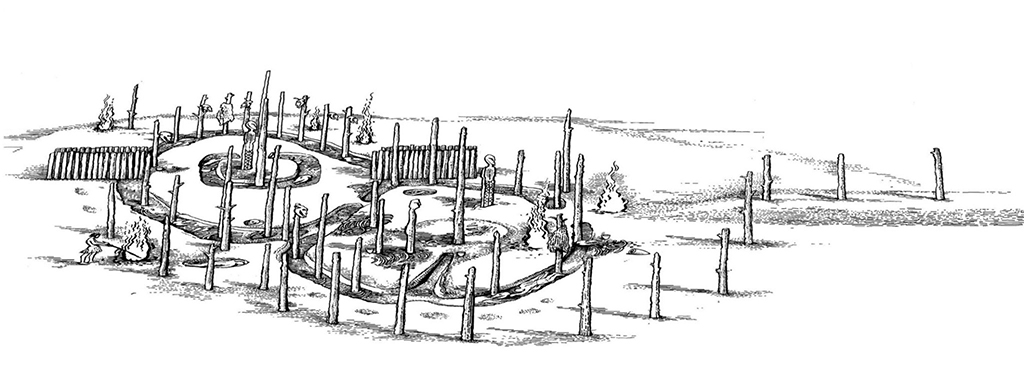

Since then, excavations were launched in the area by archaeologists Tamila Potemkina and Mikhail Vokhmentzev. Interestingly, at the beginning scientists expected to find a large settlement, but the discoveries encouraged them to rethink the area as a ritual circular place with a ditch. It was an extraordinary assumption because nothing of the kind dated to the Eneolithic period (early 3rd millennium BC) had been found before in Russia. Further excavations showed that the site consisted of two circles of woodhenges built with respect to cosmology. Moreover, the astronomical research of the site demonstrated that the second circle was constructed in exactly 100–120 years after the first one. It was determined that the totem poles were set with respect to sunrise, sunset, and solstice, alongside with moon phases. One of the poles is believed to be an astronomical gnomon. It is also interesting that at their foot many remains of horses, roe deer and moose were found, probably, as an act of sacrifice after a successful hunt. Along with Stonehenge, Savín was raised on the path of seasonal animal migration, being the best place for hunting. The position of the poles also indicates that the whole monument was designed as a seasonal calendar to find the right time for hunting.

The reconstruction of Savín, Russia. Photo: New World

Unusual remains of three persons were found in a ditch of the South circle of Savín. According to a Russian archaeologist Ekaterina Trofimova, a burial was discovered containing the remains of three people of different phenotypes: a young woman with Uralian traits and two men with Mongoloid and European (Mediterranean) traits, respectively. As in the famous grave of a shaman woman from Bad Dürrenberg, Germany (6500 BC) these remains were covered in red ochre. The mass of pigment was found across the site and is known to be used for ritual acts as a symbol of fire. These important remains were transported to a laboratory after excavations and their whereabouts are still unknown. Archaeologists believe that these remains may reflect close links between people of southern and western territories.

Read more: Fabergé — the legendary jewellery firm in London and St. Petersburg

It is also known by ceramic finds that Savín was attended by people of various cultures in West Siberia, among which are Lipchinsky, Sosnovy Ostrov, Shapkul, Andreevo. Interestingly, that settlements of the Lipchinsky culture were at the extraordinary distance of 300 km from Savín. According to Ekaterina Trofimova it might be explained by marriages between different cultural communities. It is also significant that ceramics were made by predominantly women, therefore patterns were transferred from mother to daughter. When marrying outside of their culture, women kept their own cultural ornamental tradition. Thus, they probably gave ceramic vessels to their husbands to use for Savín rituals after hunting.

The 3D reconstruction of Woodhenge. Photo: English Heritage

Proceeding from a location of Savín it is also possible to assume that this ritual place united several cultural communities and, probably, was a place of cultural interconnections and mutual influence.

The archaeologist Ekaterina Trofimova presumes that a tradition of circular settlements and ritual places was likely entered into this region from the West because of the influence of The Cucuteni-Trypillia culture, which was replaced by the Yamnaya culture. People of this culture migrated hundreds of miles from West to East in search of feeding ground for their horses and metal mines, thus reaching the Minusinsk Hollow. Although there no ceramic artefacts of Yamnaya culture were found in Savín, their settlement was near the site, and it is likely they brought the tradition of circular monuments to this area from the West.

After the discovery of Savín, two circular ritual places were discovered in the area, Slobodchiki and Veligany. Interestingly, as with other European monuments, they stopped functioning approximately the same time in about 2500 BC, a period when a stone circle of Stonehenge was constructed.

Plan of Savín

Arkaím

a circular fortified settlement, 2050 – 1900 BC

Another archaeological site Arkaím is often wrongly called “Russian Stonehenge” because of its circular shape. In fact, Arkaim was a settlement of metal-makers of the similar period to Stonehenge, it was never used as a ritual landscape.

The site was found in 1987 by a team of archaeologists headed by Gennady Zdanovich, who was sent to check the area in the Chelyabinsk region before the construction of a water reservoir. The unusual terrain induced scholars to launch excavations. The archaeological study resulted in a fascinating discovery of the largest settlement of 25 belonging to the Sintashta culture, genetically linked to the Indo-European Yamnaya culture from Eastern Europe. The archaeologist and researcher of Arkaim Ivan Semyan believes that people migrated to the West, the British Isles, and to the East, the Southern Ural, and had likely the same Indo-European ancestors long before the relocation.

The reconstruction of Arkaím

As mentioned before in the article, people of the Yamnaya culture were skilled in animal husbandry and metal mining. They moved to the East in search of feeding grounds for domestic animals, horses, and metal. The area of the Southern Ural provided ideal conditions; therefore, they began to strengthen their position by raising fortified settlements, one of which was Arkaim.

The settlement has a closed circular shape with signs of extension caused by the increasing of population. The circle is divided by sectors used as shelters for people and domestic animals. In the middle of it there is a square probably designed for communal gathering, but it doesn’t contain any evidence of a ritual place and social hierarchy. According to the archeologist Ivan Semyan, there is little known about beliefs of this culture, but burial places are well preserved and widely spread in the area.

The burial mound found close to Arkaim in 1982 featured a rich hoard: remains of animals, knives, axes, arrowheads, jewelries, and ceramic pots. However, the most intriguing thing is that several burials contained wheels of ancient chariots. This extraordinary discovery allowed reconstruction of a chariot and initiated further studies with striking results. Among the findings of the site were bit shanks, a part of an ancient bridle set attached to the ends of the bits to secure them in the mouth of a horse when riding. The research revealed that these bit shanks are identical to those widely used in Mycenae. For many years Russian scientists believed that this unusual and effective type of bit shank was brought from the West. However, in 1995 a group of archeologists with Dr. Nikolay Vinogradov and Prof. David Anthony determined by radiocarbon dating that the chariot was built in 2100 BC, long before the Mycenaean civilization appeared. Nowadays, archeologists can clearly trace the path of transmitting this technology: from the Southern Ural to Volga region, then the Black Sea Coastal area, and the Balkan Peninsula before reaching the Peloponnese.

Read more: Modernist legend Henry Moore and his muse Irina Radetsky

A group of archeologists headed by Ivan Semyan and Igor Chechushkov conducted an experiment and reconstructed the chariot using technologies and materials of the epoch to check the effectiveness of this method of riding. The results of this archaeological experiment are shown in a documentary Arkaim. The Chariot of Time that will be aired in 2022.

The Sintashta sites feature various signs of cultural and trade exchange with the advanced centers of that period. Being a metal periphery, this region probably provided Europe and Ancient Near East with raw materials through the Balkans and Caucasus. In the Southern Ural in the period of the late Bronze Age, there were found Egyptian faience jewelries and pieces of cotton from India.

The spectacular finds of recent years across Europe clearly point to various interconnections of the ancient world, which was likely always global. However, there is one thing we can be sure of, the ancient world never wanted to be isolated, because mutual intercultural links are essential for our development regardless of the time.

Exhibition “The world of Stonehenge”

- 17 February – 17 July

- British Museum

- More information and tickets

Julia Mints

Cover photo: Robert Anderson/Unsplash

The article was created with support of Russian archeologists:

Ivan Semyan, an archeologist; a head of the Laboratory of Experimental Archaeology of the Eurasian Studies, South Ural State University; a director of Experimental Archaeology Association “Archaeos”

Ekaterina Trofimova, an archaeologist, research fellow of the Centre of historical and cultural studies “Astra” (Chelyabinsk); a member of Experimental Archaeology Association “Archaeos”

Read more:

Composer Pyotr Tchaikovsky in London: impressions, recognition and success

How Diaghilev’s “Saisons Russes” influenced the European art world of the 20th century

Flappers — emancipated women of the 20s in the West and in Russia

SUBSCRIBE

Receive our digest once a week with quality Russian events and articles