Fabergé — the legendary jewellery firm in London and St. Petersburg

The new grand exhibition “Fabergé in London: Romance to Revolution” recently opened at the Victoria and Albert Museum — it tells the story of the king of jewellers Carl Fabergé, whose firm is considered a symbol of Russian luxury and elegance throughout the world. It was in London, in 1903, where the first foreign Fabergé boutique was opened, and for a long time it remained the only branch of the firm in Western Europe. Afisha.London had visited the grand exhibition in V&A and tells about the jewellery that Carl Fabergé made for Russian emperors and British monarchs.

This editorial is created in partnership with Astteria London.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, warm relations were established between the monarchs of Great Britain and Russia, and this contributed to the fact that the first overseas branch of the House of Fabergé was opened in the British capital. Officially, the boutique was in business until 1915, but, according to some sources, it remained open up to the revolutionary events in Russia in 1917. The most coveted of all Fabergé products made for the monarchs of both countries were luxurious Easter eggs, which Carl made according to the principle of a Russian nesting doll: inside each fabulously expensive egg made of precious stones and metals was hidden a dazzling surprise. At the exhibition at the Victoria and Albert Museum, the British public will for the first time see three Fabergé Easter eggs from the collections of Russian museums: the Moscow Kremlin, the Alexander Palace and the Romanov Tercentenary eggs.

- Hen Easter Egg. Photo: Fabergé Museum

- Moscow Kremlin egg

How did Fabergé Easter eggs come to be?

The most “imperial” jewellery brand originated on Bolshaya Morskaya Street in St. Petersburg, where in 1842 the Germanized Frenchman Gustav Fabergé opened his jewellery store. The sonorous surname, talent and fashion for everything French, which at the time reigned in Russia, brought the jeweller success and recognition. In 1846, Gustav and his wife Charlotte had a son, Carl, to whom his father passed on his knowledge of jewellery-making and the ability to travel to Western Europe. Carl received his primary education at St. Anne’s Gymnasium for the children of German settlers, then continued his education in Dresden and visited many museums, galleries and famous jewellers in England, Germany and France. By the age of 26, the future jewellery genius returned to St. Petersburg and 10 years later became the general manager of the Fabergé firm. It is thanks to him that the brand became known throughout Europe and was associated with luxury and high status.

In 1882, at the Russian Art and Industrial Exhibition in Moscow, skilfully made unusual Fabergé products attracted the attention of Emperor Alexander III. Thanks to the royal patronage, Carl received the titles of His Imperial Majesty’s and the Imperial Hermitage’s official jeweller. It is also believed that it was Alexander III who came up with the original idea of bejewelled eggs as an Easter gift. The Fabergé firm made the first egg in 1885 — it was an imitation of a chicken egg with a golden chicken instead of the “yolk”, inside which was a ruby crown. Alexander III presented the chicken egg to his wife Maria Feodorovna, and it became the first in a series of 52 Easter eggs made by Fabergé for the House of Romanov. By the way, one of the most incredible items in this series is the Moscow Kremlin egg with a clock and a music box, which Nicholas II ordered for his wife Alexandra Feodorovna in 1906. The egg is kept in the Kremlin Armory and has never left Russia, but from November, Londoners will be able to see this piece of jewellery at an exhibition dedicated to the House of Fabergé at the Victoria and Albert Museum. Two other Easter eggs, which will be shown to the British public, Alexander Palace and Romanov Tercentenary, were also made by order of Nicholas II as a gift to his wife.

- Alexander Palace egg. Photo: Moscow Kremlin Museum

- Romanov Tercentenary egg. Photo: Moscow Kremlin Museum

A notable feature of Fabergé Easter eggs is that each item is symbolic and unique in design — the manufacturing process was incredibly painstaking and took the craftsmen about a year. By the way, not only men worked in Carl Fabergé’s firm — among the jewellers there was one woman, Alma Pil. She invented a style called “frost on crystal” and became the author of the unusual Winter egg, which Nicholas II ordered for his mother Maria Feodorovna in honour of the 300th anniversary of the Romanov dynasty. The Winter egg is valued at $9.5 million and has long been considered the most expensive Imperial Fabergé egg, until in 2007 its record was broken by the diamond and pearl-adorned Rothschild egg, which was sold at Christie’s for an incredible price of $18.5 million (£8.9 million). Interestingly, the Rothschild egg is one of the few eggs made not for the House of Romanov, but for the Rothschild dynasty. Nevertheless, it became the most expensive Fabergé piece ever sold at an auction, and now it is in the collection of the Hermitage in St. Petersburg.

- Winter egg

- Rothschild egg. Photo: Hermitage Museum

Which British monarchs were interested in Fabergé?

The building on Bolshaya Morskaya, 24 in the centre of St. Petersburg, where Carl Fabergé lived and worked, quickly became a place of attraction for the rich and royal persons, and orders for products known for their impeccable quality poured in an endless stream. According to the Fabergé Museum, over the entire period of the firm’s existence, about 300,000 items were produced: jewellery, bejewelled eggs, cigarette cases, jewellery boxes, dishes, stone-cut animal and flower figurines, still lifes made of precious metals. Among the members of the imperial family, personal gifts from Fabergé for European relatives were popular, especially in three countries: England, Denmark and Germany. Experts claim that the Empress Dowager Maria Feodorovna played a key role in the opening of the London branch in 1903. She often visited her sister Alexandra, the wife of Edward VII, and brought gifts from the court jeweller, which bewitched the British queen.

An important aquamarine and diamond tiara, Imperial presentation box, Third Imperial Egg, Cigarette case

Follow us on Instagram for news about Russian life and culture

The London branch was initially located at a small premises at 48 Dover Street, and the boutique itself was opened with the expectation of such clientele as the English aristocracy and the royal family. Special rooms were allocated for Queen Alexandra, which she could visit at her discretion to try on jewellery and observe the work of the store — such amenities, by the way, did not exist for the monarchs in St. Petersburg. While Maria Feodorovna was a fan of jewellery, her sister Alexandra adored stone-cut figurines — this is how animals and birds from the royal zoo became a source of inspiration for Fabergé craftsmen. In 1907, for the birthday of his wife, Edward VII personally ordered a series of animal figurines inspired by the inhabitants of the royal residence in Sandringham. On this occasion, the Russian sculptor Boris Frödman-Cluzel arrived in London to create the exact wax copies of the beloved animals of the royal couple. After Edward VII approved the wax models, they were shipped to St. Petersburg, where they were used to make figurines from various minerals and precious stones. By the way, at the upcoming exhibition at the Victoria and Albert Museum you can see the king’s favourite pet — the Norfolk Terrier called Caesar, made of chalcedony. To date, 170 of the 250 stone-cut Fabergé animal figurines are in the personal collection of Elizabeth II.

- Mosaic egg. Photo: Royal Collection Trust

- Colonnade egg. Photo: Royal Collection Trust

Also, the British Queen owns four Fabergé Easter eggs, three of which are imperial: they came to the royal collection from auctions or were bought from private individuals. Basket of Flowers is the embodiment of Nicholas II’s love for his wife, the Mosaic egg, unique because it was made by the woman designer Alma Pil, and Colonnade egg with a clock and a lovely cupid on top. Colonnade symbolises the temple of love — it was presented to Alexandra Feodorovna in honour of the birth of Tsarevich Alexei. The fourth egg from the collection of Elizabeth II — Twelve Panel — was ordered by the Russian entrepreneur Kelch as a gift to his wife Varvara.

The revolution in Russia and the fate of the Fabergé boutique in London

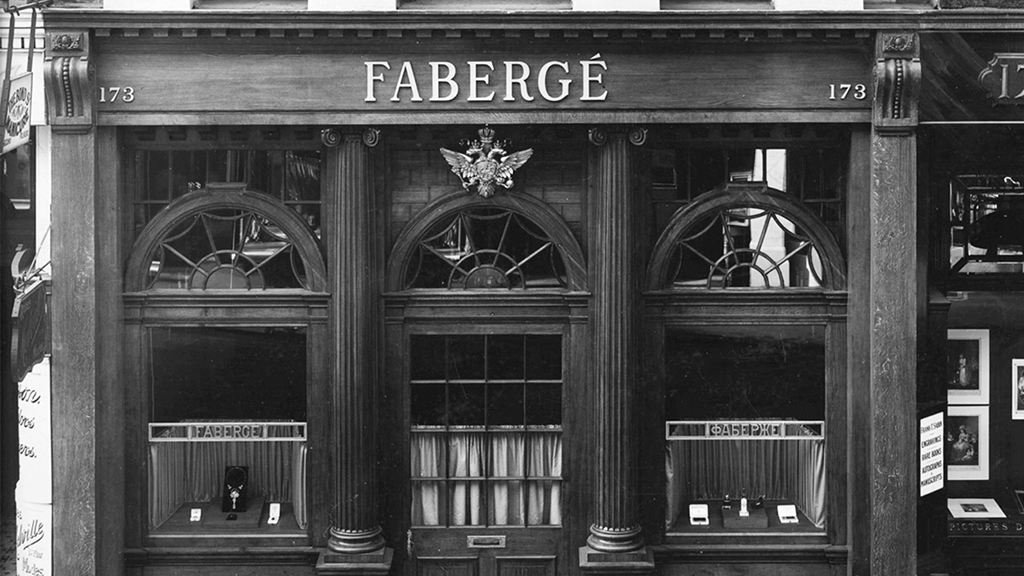

The Dover Street boutique was open for only a couple of years, and in 1906, Carl Fabergé opened a fashionable store at 173 New Bond Street, which, according to curators of the Victoria and Albert Museum, attracted clientele from around the world in the form of aristocrats, business titans and celebrities. After the death of Edward VII, King George V became the main privileged customer of the boutique. And since 1909, Fabergé’s youngest son Nicholas was appointed head of the London branch — he was a talented designer, who studied with the famous painter John Sargent and chose the Englishwoman Marion as his wife. By the way, on the British market, the House of Fabergé sold products with a slightly different artistic imprint, which was more familiar to the British — with simpler shapes and restrained ornaments. The boutique offered a set of expensive jewellery for £1,400, as well as cute trifles at more modest prices: miniature Easter eggs for 10 shillings, popular jade elephants for £11, silver cigarette cases for £7 and much more. Fabergé souvenirs presented as a gift were considered a symbol of happy moments and a sign of good disposition.

- Basket of Flowers. Photo: Royal Collection Trust

- Twelve Panels egg

However, with the outbreak of the First World War, the demand for jewellery fell sharply, and, in addition, Carl Fabergé was suspected of being under German control. All this led to the fact that in 1915 the London branch was closed, although unofficially the store continued its work until 1917. In 1918, the House of Fabergé was nationalised by the Bolsheviks, and Carl was forced to flee abroad, leaving in Petrograd all the accumulated family wealth worth at least 4 million gold roubles. His two sons, Agathon and Alexander, were arrested in Russia, while his wife Augusta and her son Yevgeny managed to leave for Finland. Partial family reunification took place in 1920 in Switzerland, but by that time Carl was already seriously ill. On September 24, 1920, at the age of 74, the king of jewellers died in Lausanne and was buried in the Grand Jas cemetery in Cannes.

Boutique at 173 New Bond Street (1910)

The heirs of the jeweller lost their rights to the Fabergé brand back in 1951, but in 2007 a group of investors bought out the rights and founded the Fabergé Heritage Council, which included two great-granddaughters of the jeweller — Tatiana and Sarah. As a true heir to the dynasty, Sarah Fabergé from the age of 16, together with her father Theo, the son of Nicholas Fabergé — the head of the London branch, developed the design of Easter eggs and worked for some time in London. In her interviews, the great-granddaughter of the legendary jeweller says that her mission is to recreate the authentic spirit of Fabergé, which has no equivalent in the world. Now in London there are 5 boutiques and representative offices of the House of Fabergé: in Harrods, on Cathedral Piazza, in the Frost of London boutique at 22 Brook Street, in the Deakin & Francis boutique at 19-21 Piccadilly Arcade and in the Swiss Gallery of the Marriott Grosvenor House hotel.

- Exhibition: Fabergé in London: Romance to Revolution

- Opened from November 20, 2021 to May 8, 2022

- Contact us to book a private tour in Russian or English

Afisha.London would like to thank you Astteria London for collaboration.

Astteria — luxury jewellery for effortless elegance

Irina Latsio

Cover photo: Peacock egg, Henrik Wigstrom, 1908

Read more:

Modernist legend Henry Moore and his muse Irina Radetsky

SUBSCRIBE

Receive our digest once a week with quality Russian events and articles