Modernist Legend Henry Moore and His Muse, Irina Radetzky

Sculptor and innovator Henry Moore stands as a true British legend. Focusing primarily on female figures, Moore drew inspiration from his cherished wife, Irina Radetsky, who served as his muse for six decades. In his paintings, Moore deftly captured the grim realities of war while simultaneously championing the resilience of life. He seamlessly integrated his sculptures into natural landscapes, enhancing their organic essence. Moreover, Moore had a fondness for sketching fluffy sheep, which came to symbolise the expansive beauty of his native England. Afisha.London magazine looks back at the key milestones in Henry Moore’s illustrious career and explores the unique characteristics of his “fluid” artworks.

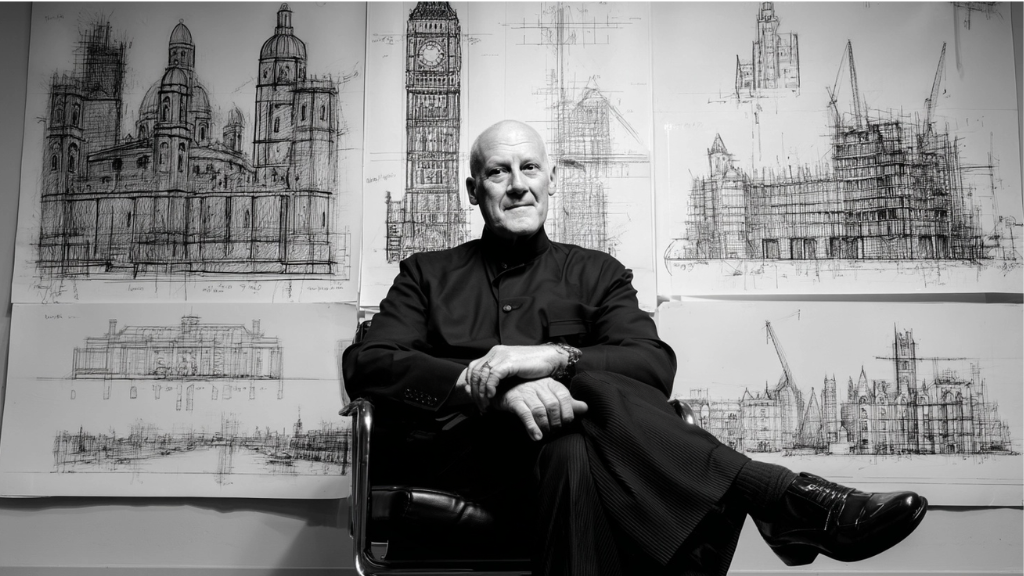

For more than seven decades, the art of Henry Moore has been celebrated for its exceptional craftsmanship, earning high regard on an international scale. In 1948, Moore was awarded the International Prize for his iconic sculpture, “Reclining Figure,” at the Venice Biennale, and a year later, he was heralded as the greatest sculptor of the 20th century. The value of Moore’s work continues to escalate; in 2012, one of the five existing copies of “Reclining Figure” fetched £19.1 million at a Christie’s auction in London. This extraordinary sale positioned Moore as the second most expensive 20th-century artist, surpassed only by the expressionist Francis Bacon. In 2016, another iteration of the same sculpture broke previous records, selling for an astounding £24.7 million. Without question, Moore is a seminal figure in the realm of modern art. Moreover, his life story serves as a compelling testament to how a humble childhood aspiration can metamorphose into overwhelming success and global acclaim.

A young romantic in life and at war

It appears that many great figures have a sense of their destiny from an early age, and such was certainly the case with young Henry Moore. Born on 30 July 1898 to a miner’s family in the town of Castleford in West Yorkshire, Moore showed a flair for the arts from a tender age. By the time he was 11, he had already been captivated by the masterpieces of Michelangelo and nurtured dreams of becoming an eminent sculptor himself. However, fate had other plans, as he first had to confront the grim realities of the First World War. Moore often reflected on experiencing the war in a ‘romantic haze,’ with aspirations of heroism. He became the youngest member of the Prince of Wales’s rifle regiment and even survived a gas attack during the infamous Battle of Cambrai in France.

Years later, amidst the devastation of World War II, Moore’s views on war evolved dramatically, shifting to consider it fundamentally anti-life. This newfound perspective would profoundly influence his art, resulting in sculptures that exuded a sense of life’s indomitable spirit. Seamlessly integrating with their natural surroundings, Moore’s works seemed as though they had been sculpted by the hand of nature itself.

- Henry Moore while serving in the Civil Service Rifles (1917). Photo: Henry Moore Foundation

- Henry Moore at work (1927). Photo: Tate

However, at this juncture, Moore was merely at the commencement of his journey towards crafting a style that would ultimately have no parallels in the world. As a former serviceman, he was granted a scholarship to further his education. In 1919, he enrolled at the Leeds School of Art, which has since been renamed Leeds Arts University, before advancing his studies at the Royal College of Art in London. Post-graduation, he travelled to northern Italy—a trip that left an indelible mark on him—as well as to Paris, where he was enthralled by a replica of the Toltec Chac Mool figures, which would later serve as inspiration for his own work.

Read more: Pyotr Tchaikovsky in London: a journey of impressions, acclaim, and triumph

Upon his return to England, Moore continued his affiliation with the Royal College of Art, accepting a teaching position in the sculpture department. It was during this period, spanning from 1924 to 1932, that the initial inklings of his unique style began to surface. His primary mediums of choice were stone and wood.

Living in London during the roaring 1920s afforded Moore the opportunity to immerse himself in various historical epochs, thereby allowing him to diverge from the classical paradigms extolled by his academic mentors. With fervour, he frequented renowned institutions such as the National Gallery, the Victoria and Albert Museum, the Tate, and the British Museum’s ethnographic exhibitions. He delved into the ancient art of Egypt, Mesopotamia, and pre-Columbian Mexico, gaining a profound appreciation for the plasticity of these ancient civilisations.

Meeting his muse and a new life

Employment at the Royal College of Art serendipitously led Henry Moore to his future wife, Irina Radetsky, who was then one of his students. Born in 1907 in Kiev to a Russian-Polish family, Irina initially pursued ballet studies in Moscow. However, the upheaval of the Russian Revolution in 1917 resulted in the loss of her father, prompting her and her mother to relocate to Paris. There, she married a British officer and eventually moved to Great Britain to reside with her stepfather’s relatives in Buckinghamshire.

View the film about Fabergé exhibition in London

Her fortuitous meeting with Moore coincided with his inaugural solo exhibition in 1928 at London’s Warren Gallery. At that time, the art world was still mired in the conservative romanticism of the Victorian era. As a result, Moore faced considerable criticism for the perceived immorality and distortion of human forms present in his sculptures. Despite this, Moore remained unyielding in his artistic pursuit. He sensed that he was crafting a wholly original style, one imbued with a potent life force and unencumbered by classical constraints.

- Henry Moore and Irina Radetsky. Photo: Henry Moore Foundation

- Reclining Figure (1951). Photo: National Galleries of Scotland

Moore found his artistic muse in the contours of the female form, with his beloved Ukrainian wife, Irina, serving as a perpetual model. In his sculptures, he likened the female body to a natural landscape: knees and chest became analogous to mountains, the ovals of shoulders and hips transformed into hills, while voids took on the symbolic resonance of caves. Among his most iconic female sculptures is “Reclining Figure,” executed in five distinct versions using various materials. The bronze iteration of this seminal work debuted on London’s South Bank as part of the British Festival in 1951 and now resides in the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art.

Moore’s affection for his first and only muse, Irina, swiftly blossomed into a robust partnership, culminating in their marriage in 1929. Post-wedding, the couple relocated to a Hampstead studio at 11a Parkhill Road, where they resided until 1940. A blue plaque on the building now serves as a historical marker for those passing by. During that era, Hampstead, with its expansive park and rustic ambience, became a sanctuary for avant-garde artists. Both Henry Moore and his wife were integral members of this artistic community. Interestingly, the Russian ballerina Anna Pavlova was also a resident of the area.

Henry Moore at work in his studio in Hampstead. Photo: Henry Moore Foundation

Another war and new artistic findings

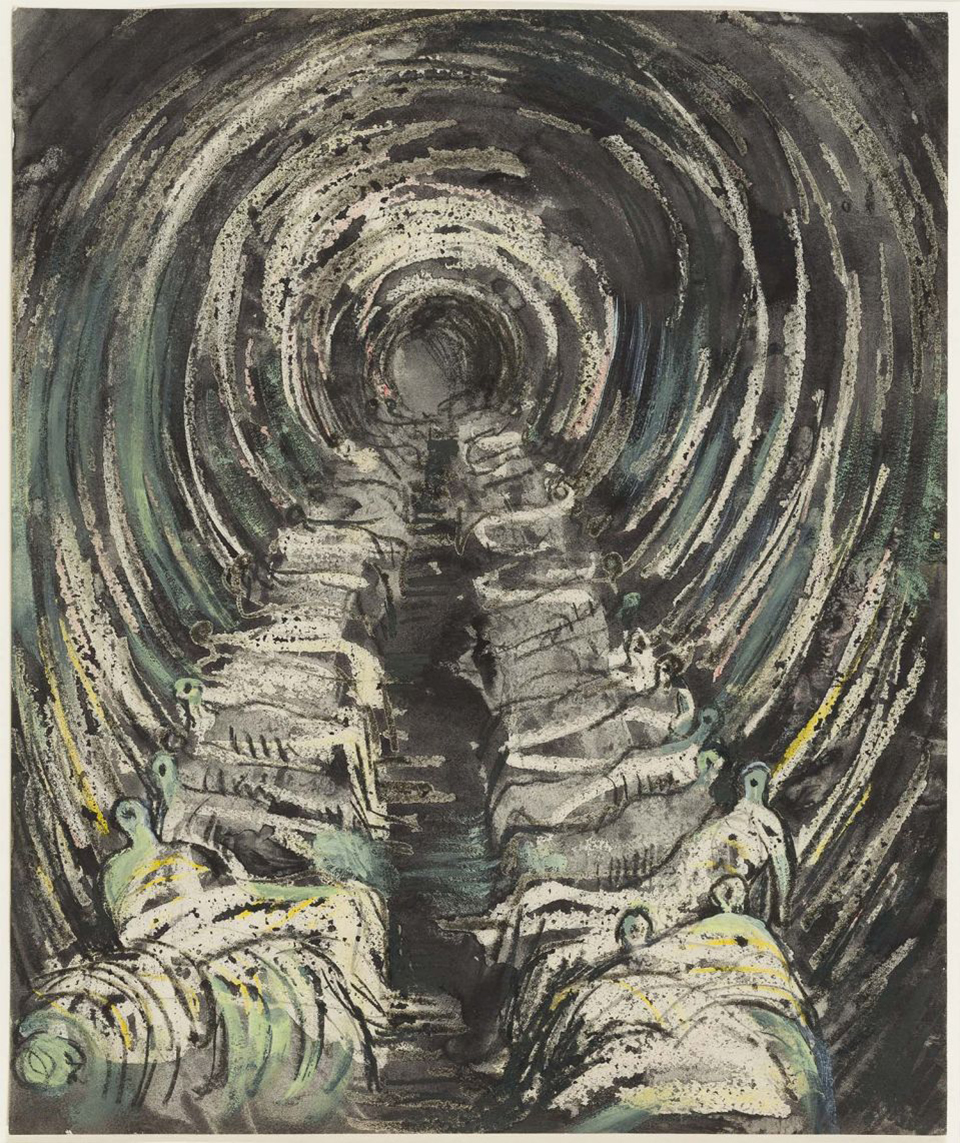

The trajectory of the artist’s life took an abrupt turn during the Second World War. In 1940, a bomb struck their Hampstead residence, prompting the couple to relocate to Hertfordshire. It was during this tumultuous period that Henry Moore emerged as a notable war artist and began to gain recognition beyond the shores of the UK. His poignant graphic sketches, which have since found homes around the globe, captured the grim reality of Londoners seeking refuge from Nazi air raids in the dank tunnels of the London Underground during 1940-41. Amidst these bombings, approximately 10,000 civilians lost their lives in the British capital. Moore’s series of works, known as the “Shelter Drawings,” served as a call for solidarity amidst the prevailing despair.

Read more: Leo Tolstoy in London: shaping the british literary landscape

In 2011, some of these sketches were featured in an exhibition titled “Blitz and Blockade — Henry Moore at the Hermitage” in St. Petersburg. The curators drew insightful parallels between Moore’s wartime graphics and the sketches created by architect Alexander Nikolsky, who had similarly documented the human condition while confined to the basements of the Hermitage Museum during the blockade of Leningrad.

- Henry Moore — Tube Shelter Perspective (1941). Photo: Henry Moore Foundation

- Henry Moore — Seated Mother and Child. Photo: Sotheby’s

Following the birth of his daughter Mary in 1946, Henry Moore revisited his favoured themes of female figures and motherhood, drawing upon the iconic motif of Madonna and Child. One surreal interpretation of this theme, the marble sculpture “Madonna and Child,” graces the interior of St. Paul’s Cathedral in London.

In a quirkier vein, Moore also found artistic inspiration in the fluffy sheep that grazed in the spacious pastures of Perry Green in Hertfordshire, where he resided with his family. One day, while observing sheep from his workshop window, Moore rapped on the glass to catch the attention of one particular animal. The sheep lifted its head briefly, providing Moore just enough time to capture its likeness. This moment sparked a series of sketches and drawings that would eventually evolve into sculptures.

However, one of Moore’s most captivating and romantically charged works remains the bronze sculpture “King and Queen” (1952). Inspired by a significant period in British history—the death of King George VI and Queen Elizabeth II’s subsequent ascension to the throne—the piece features models based on Moore and his wife, Irina. It also draws inspiration from ancient Egyptian dual statues symbolising stability and wisdom. The sculpture was cast six times, and one of these casts is proudly displayed at Tate Britain.

- Henry Moore — King and Queen (1952-53). Photo: Jonty Wilde/© Henry Moore Foundation

- Henry Moore — Sheep Resting (1974). Photo: Tate

Calm life at Perry Green

For nearly five decades, Henry Moore resided at the Perry Green estate, transforming the sprawling property into a remarkable showcase of British public art. Alongside him, his wife Irina devoted herself to the landscaping of the garden that enveloped their home, whilst Moore populated the space with his distinctive metal and stone sculptures, effortlessly melding them into the natural surroundings. Today, the estate has been meticulously restored to maintain the appearance it held under Moore’s ownership: a humble brick house, a floral garden punctuated by sculptures, and the tranquility of village life.

Read more: Rudolf Nureyev: an emigrant, who became a ballet legend

From 31st March to 31st October, Perry Green opens its doors to the public. Visitors have the opportunity to explore Moore’s personal workshops and residence, amble through the renowned garden gallery, and roam the extensive 70-acre grounds that play host to the artist’s monumental works. The estate also serves as the headquarters for Moore’s personal foundation, established during his lifetime with Irina and their daughter Mary appointed as trustees.

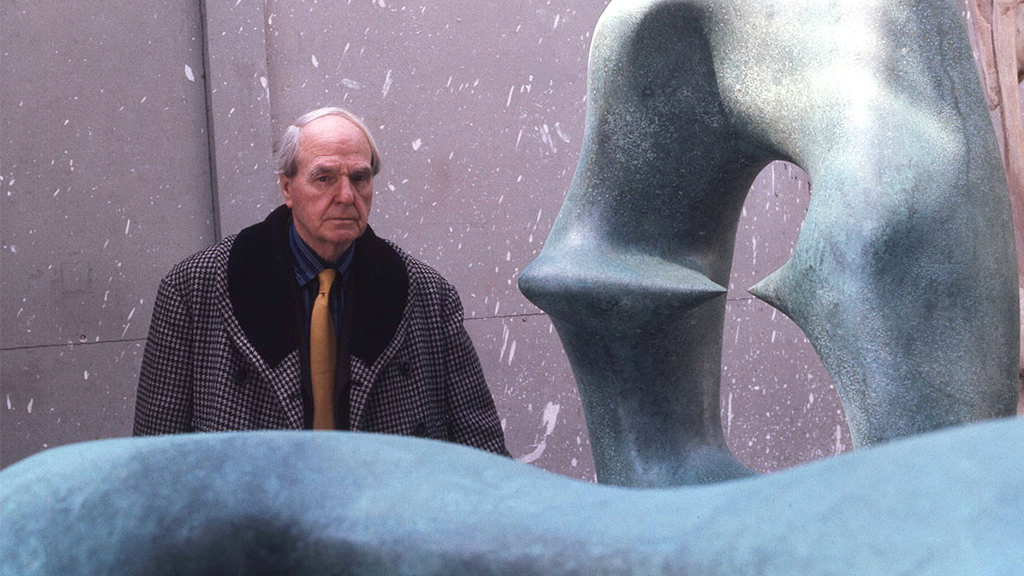

Henry Moore passed away on 31st August 1986 at the age of 88, in Perry Green. At the time of his death, he was the world’s wealthiest and most accomplished sculptor, leaving behind an indelible legacy that continues to be celebrated.

While meandering through the streets of London, one may easily stumble upon one of Henry Moore’s iconic monuments. His stone “Arch” elegantly graces Kensington Gardens, while the “Locking Piece” finds its home on the embankment near Tate Britain. Another renowned sculpture, “Knife Edge Two Piece,” is prominently positioned opposite the House of Lords in the British Parliament.

The Russian public had the opportunity to fully appreciate the breadth of Moore’s oeuvre only in 2012. On 21st February, a comprehensive retrospective of his work was unveiled at the Moscow Kremlin Museums. The exhibition showcased pieces from Moore’s personal foundation, Tate, the British Museum, as well as select private collections. Notably, the guest of honour at the opening event was Moore’s daughter, Mary Moore.

Irina Latsio text/ Lia Shapiro and Margarita Bagrova translation

Cover photo: Allan Warren, CC BY 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Read more:

Emmeline Pankhurst in St. Petersburg: the suffragette movement in Britain and Russia

Anna Karenina: a Russian classic reimagined in Britain

Yuri Gagarin in London: how to impress the Queen and become a British hero

SUBSCRIBE

Receive our digest once a week with quality Russian events and articles