A short guide to being a happy parent of a happily multilingual child

Almost every family in emigration is faced with the fact that their children find themselves in a multilingual environment. Thus, maintaining several languages becomes a routine task for parents and their children. And what is the most efficient way to do this? How to gently adapt to a new language environment and at the same time preserve your native language? Our columnist Darya Protopopova, writer, who holds a PhD in English Literature from the University of Oxford, and founder of London Group of Multilingual Writers shares her opinion on this issue.

Hello and congratulation on being a parent of a multilingual child — a child who is getting to know more than one language! I am a multilingual person myself and my children (twin girls) are also growing up in a multilingual family (English, Italian and Russian). For us each day is filled with fireworks of words from different languages: we talk about my children’s school in English, I tell them to hurry up and eat their breakfast in Russian; in the evening, they may get a Skype call from their grandparents in Italian. And while this is exciting and stimulating, for me as a parent and a teacher it is also a source of worry: am I doing enough to support my children’s learning of Russian? or English? are they getting confused by the three languages? should I be doing anything about their grammar in Italian, which is very weak?

Follow us on Twitter for news about Russian life and culture

I’ve been worried about these questions for a long time, to the point of getting overly anxious about my children’s language education. But then two things happened.

First, I had an opportunity to do research on bilingual and multilingual learning. There is a whole library of books, articles and, more recently, blogs (such as http://multilingualparenting.com/) written on how children are learning to be multilingual. One point on which all those researchers agree is that successful multilingual learning can only be based on an unwavering positive attitude towards a child’s knowledge. In other words, whatever knowledge of a language (or languages) a child has, it should only be assessed in a positive light. I’ll give you an example. At the beginning of this article I said that my children’s Italian grammar is ‘very weak’. This is how teachers often talk about children’s language abilities: ‘his handwriting is very poor’, ‘she knows only a few words’, ‘his English/Russian/etc. is weak’. Of course, teachers (and parents) make these remarks out of good will, as a way of identifying where a child needs help. But this way of thinking about language learning, as if there is a standard level that a child needs to achieve, after which their knowledge of a language will supposedly become ‘good’, ‘strong’ or even ‘complete’, is misleading. Language learning is a life-long process; even native speakers are developing their knowledge of language every day, by hearing new words, forgetting old ones, applying their language to new situations.

Photo: Keren Fedida / Unsplash

In a way, language learning is like building a staircase: throughout our lives, we are putting a block on top of a block with every word we learn. So talking about a child’s ‘weak’ or ‘slow’ language development is like complaining about them already having a few blocks in place, instead of admiring what they have built and asking them to build more. It often happens that our children have already learnt a few words and are happily putting them together, but we are not happy that their language ‘staircase’ is tall enough. Parents become frustrated, children start feeling they are constantly failing in learning the language and become insecure. Instead, researchers recommend constant praise for what the child has already learnt — they recommend constant reminding a child about how much they have already achieved. Against a popular belief, such praise does not lead to a child’s complacency and refusal to learn more: on the contrary, praise gives them confidence, belief in their own abilities, and a willingness to earn more praise by speaking the language they are learning. Even by praising the child who can understand some words in a different language we support their multilingualism.

The second thing that has made me a happier parent of multilingual children is linked to the first. As my children were growing up, I could see them benefiting from what researchers call ‘the transferability of language skills’ — one of the key aspects of multilingual learning. This transferability of language skills means that what children learn in one language they can later apply to another language or languages. For example, parents often worry that if their child learns how to read in English first, it will make it difficult for them to learn how to read in another language. Research has shown that learning how to read confidently in one language only helps children become confident readers in other languages, as they had already learnt key principles of reading: e.g. associating letters with sounds, blending sounds together, making sense of a group of words. One thing that needs to be remembered though is that, naturally, children who live in a monolingual environment and are learning to read only in one language will learn faster than children who are multilingual and are grappling with more than one alphabet or more than one phonetic system. But, as I have already mentioned, this slower learning process should be seen in a positive light, as a result of a child’s richer learning environment and more complex thinking patters.

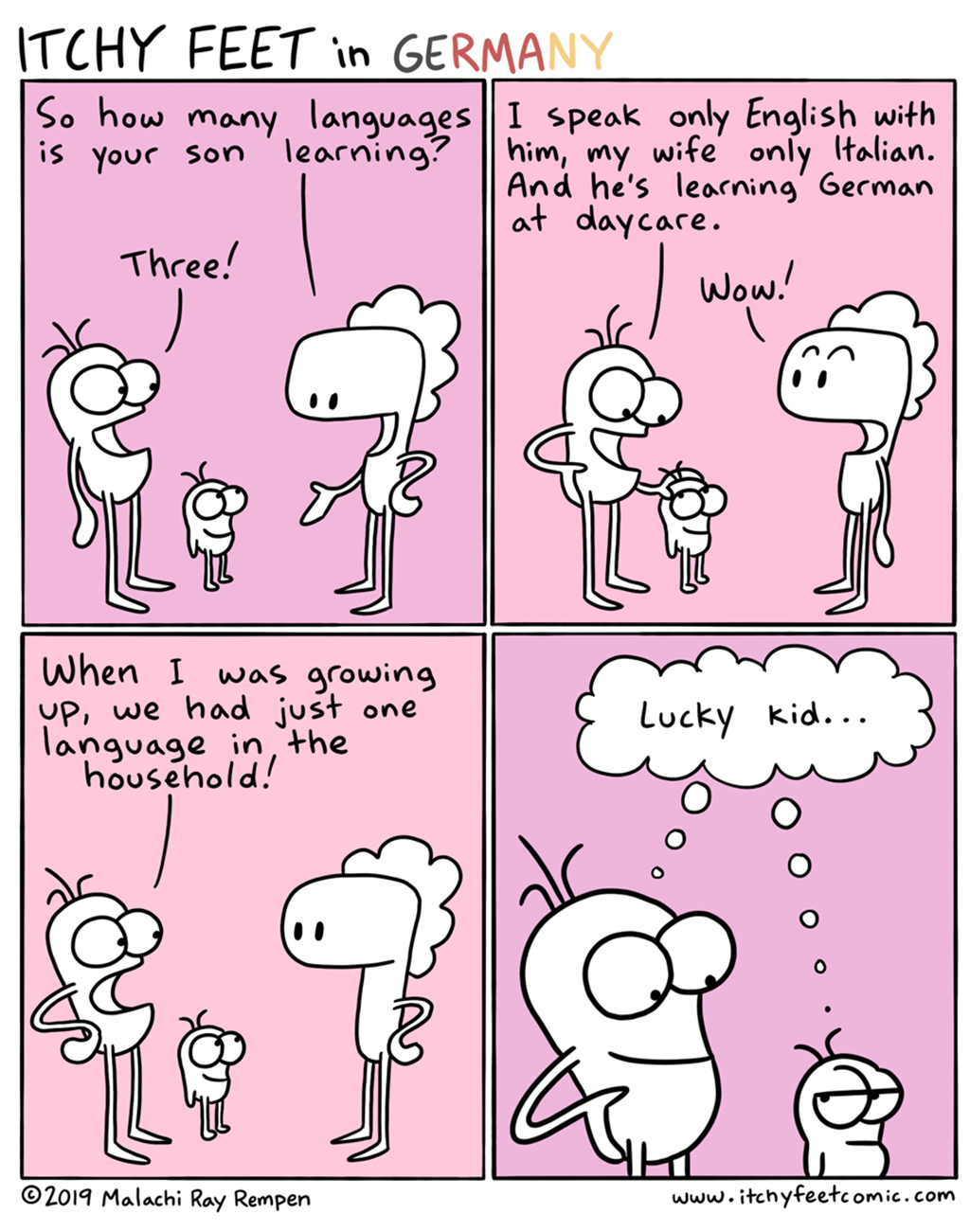

- Itchy Feet © 2018 Malachi Ray Rempen

- Itchy Feet in Germany © 2019 Malachi Ray Rempen

So, to sum up, instead of focusing on ‘poor’ or ‘weak’ areas in our children’s learning, we should focus on the fact that, by growing up in a multilingual setting, they are already doing an amazing job at exploring rich linguistic heritage and are daily building their language ‘staircases’, staircases that support each other and may not be always visible, but are nonetheless present in their minds. The better a child knows one language, the easier it is for them to study other language or languages, should they be willing to do so. Of course, the fact still remains that children learn languages more effectively if they are doing it willingly, rather than, to use an old Russian saying, ‘from under a stick’.

So here are some tips to happy and effective multilingual learning, based on the research listed below.

♦ If you want to talk with your child about learning a language, do it in a positive way. Tell the child how happy it makes you feel when they speak to you in that language. ‘Oh, mummy loves it when you speak Russian/English/Mandarin/etc to her!’ ‘Who is this good boy who is speaking French?’ ‘Well done, you know that daddy is very happy when you read Russian books!’ These phrases, even if they sound a bit sentimental, really boost children’s willingness to learn the language you are trying to get them interested in; they are much more effective than saying, ‘I told you, I don’t want you to speak in X, reply to me in Y!’

Фото: Hongqi Zhang/Alamy Stock Photo

♦ Avoid telling the child that their knowledge of an X language is ‘weak’ or ‘poor’: instead, praise them for knowing even a single word in the language they are learning. Even when you speak to them in Y, and they reply to you in X, praise them for understanding you in the first place. In the end, I started telling my children that I am proud of their understanding Russian and Italian: ‘You are amazing’, I told them, ‘You can understand three languages’. Especially as a child grows up, this pride in being able to communicate in different languages will keep them motivated to learn more.

♦ Always encourage reading and writing in whatever language the child wants to. Remember that due to transferability of language skills, if your child practises reading in one language, it will only help their reading in another language. Before I did my research, I was worried that by teaching my children to read in English, I would damage their Russian reading skills. My children would bring me English books and ask me to read those for them, and I would say no and read them Russian books of my choice instead. They would listen reluctantly and as a result would never ask me to read in Russian. Later, when I realised that such approach was counterproductive, I would always praise my children for playing with books of their choice and read what they asked me to, and would simply say that next time, Mummy would really like to read this exciting book in Russian, etc. For the first time, my children wanted to read something in Russian by syllables when I bought them books by Nina Romanova (LinguaMedia publishing house at the LinguaPlay school). I also made sure that Russian and Italian books in our house were as colourful and enticing as our English books — a good way to start is to find books about your child’s favourite cartoon characters. There is nothing wrong in showing a child a cartoon first, and only then reading a book on which the cartoon was based.

Photo: Lorelyn Medina/Fotolia

♦ Keep speaking to your child the language you want them to learn, even if they never (or very rarely) reply to you in that language. Just because they are not speaking the language, it does not mean they don’t understand it or don’t like it. It may simply mean that they don’t find it necessary to communicate to you in that language, knowing you can understand them in English — the language they are finding it easier to speak at the moment. It is only natural that if a child was born and raised, for example, in Britain, hearing English in the street, at school or on television/Internet, their default language of communication would be English. However, if a parent perseveres in speaking and reading to the child, for example, in French, the child’s knowledge of that language would develop invisibly, subconsciously, and you will soon discover that when the child meets a person who can communicate in French only (for example, a French grandparent or a monolingual French friend), they will try to speak to them in French: their passive knowledge of French will become active, out of necessity. Centuries ago, our ancestors developed language out of necessity to communicate with each other: as the article by the famous British writer Lawrence Osborne shows, even people who were not taught a language in a conventional way, would find a way of making themselves understood. Similarly, if a child realises that they need to speak a certain language to achieve something they want (e.g. tell their grandparent about their favourite toy), they will willingly speak to their grandparent in that language.

♦ This last tip is directly linked to the previous one and is based not only on research, but also on my personal experiences as a tutor and a parent. If you want your child to learn a language, create a situation in which it would become necessary for them to use that language. One example we have already looked at: children learn a language best when they have to communicate with people who understand only that language and nothing else, e.g. a grandparent or a friend. When I teach languages in one-to-one lessons, I always advise parents in addition to send their children to a hobby club where they would have to speak one language exclusively, or a holiday camp in a monolingual setting. If that is not possible, I suggest finding a pen friend or starting a diary in the language a child is trying to learn. My children learnt to write in Russian first by writing birthday cards to their multiple friends and relatives. Sometimes I would cheat and say, ‘Now you have to write the names of all those animals in Russian, because otherwise how would babushka (Russian for ‘grandmother’) understand who is who in your drawing?’ Sometimes my children would not know how to write something in Russian, in which case I would happily translate. Translation is another perfect tool for happy language learning in a multilingual environment. By telling your child what to do in two languages at once you are not confusing them: you are making them aware of wider communication possibilities (and preparing them for a possible career in translation!). Remember: the ultimate goal of them learning a language is to help them communicate with the world, so encourage them to communicate in whatever language they can, including body language, language of drawing, building, music and dancing!

Cover photo: Compare Fibre / Unsplash

Read more:

From Britain to Russia: a tradition of “Stonehenges” across Europe

Composer Pyotr Tchaikovsky in London: impressions, recognition and success

SUBSCRIBE

Receive our digest once a week with quality Russian events and articles