A patriot in exile, or the star and the death of Boris Berezovsky

London’s Almeida Theatre in Islington blew up the summer theatrical lull in the capital with its production of Patriots, the protagonist of which was the exiled Russian oligarch Boris Berezovsky. Although most British critics rated the play by the famous screenwriter Peter Morgan at 3–4*, for the post-Soviet audience, the performance will undoubtedly reveal several additional layers of consciousness. The play, starring Tom Hollander, will run from May 26 to August 19. Tickets can already be purchased via this link. Our columnist Alexander Smotrov talks about his impressions of the performance and compares them with his memories from meetings with Berezovsky in London.

The name of Boris Berezovsky, who died in the UK almost a decade ago, is still on everyone’s lips. Someone remembers his famous political and business affairs in post-Soviet Russia in the 1990s, someone remembers him for his endless lawsuits in London courts, and someone still cannot forgive him for playing a pivotal role in Vladimir Putin’s rise to power. All these and many other facets of the biography of the “great strategist” at the turn of the 20th and 21st centuries are superbly revealed by the 2,5-hour performance directed by Rupert Goold.

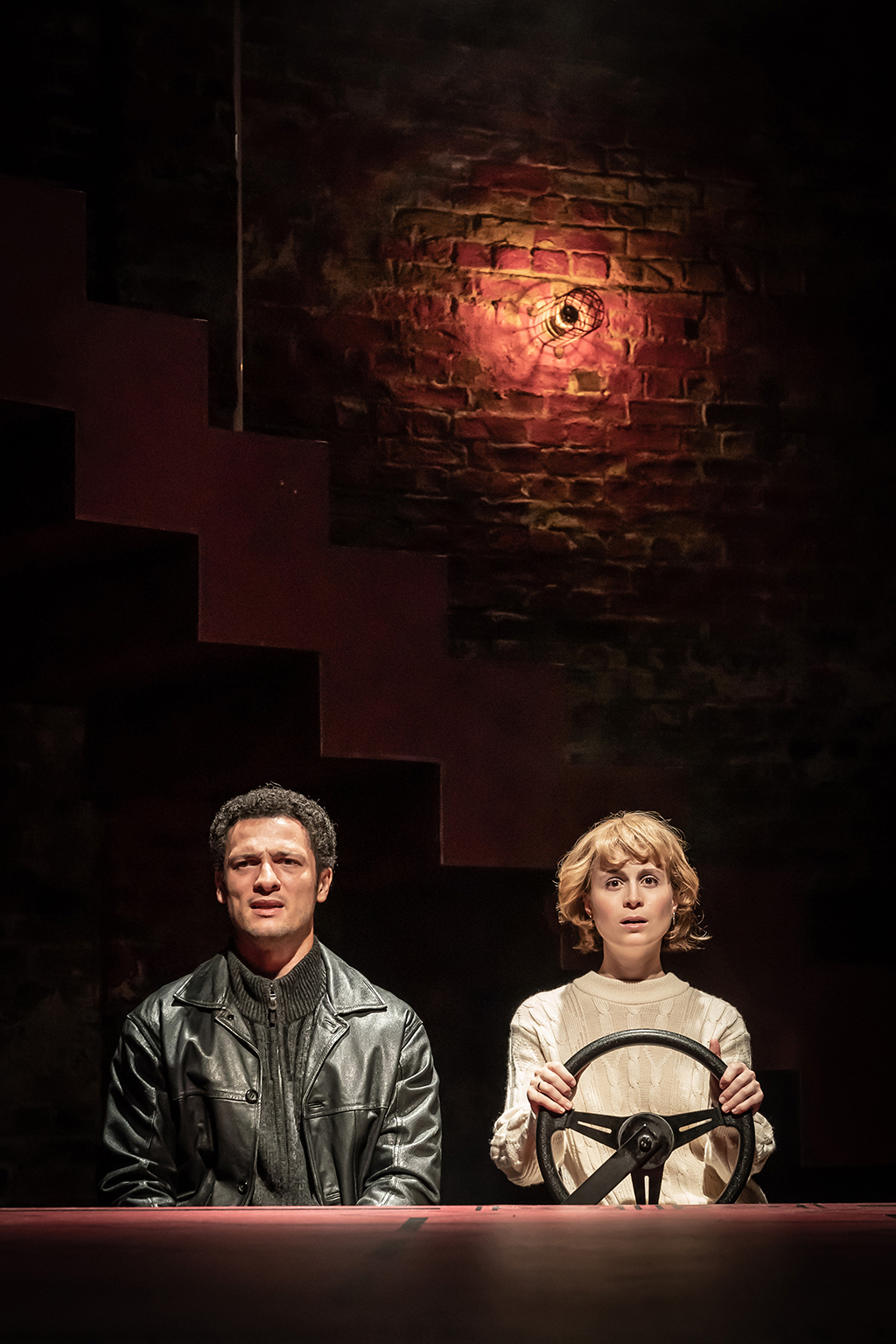

Photo: Marc Brenner

His co-author, screenwriter Peter Morgan, made a name for himself on political dramas like Frost/Nixon or The Deal about an unspoken pact between Tony Blair and Gordon Brown. He is familiar to modern audiences for his film scripts and series about the life of the British royal family, such as The Queen, The Audience, and The Crown. He works with Russian material for the first time. Still, his recognizable style is immediately noticeable in the play — he takes well-known historical facts as the reference points of the script and fills the voids between them with facts that are close to reality but still fictional. Although, in the end, it turns out not to be a biography, but a dramatization, the objective of a work of art turns out to be achieved: we see living heroes on the stage and the development of their characters, and not just a series of news headlines about them.

Don’t miss it. A new dramatic hit this fall — the production of “Dmitry” at the Marylebone Theatre

The stage looks like a dark red cross, which turns either into the dance floor of an expensive elite club of the 90s, or at the crossroads of the Kremlin’s red carpets, or into a television studio, and even to the end of the Earth, the Chukotka Peninsula. But in each case, it is a symbol of the eternal Russian crossroads, in which the future fate is decided, and events can go according to opposite scenarios, depending on the choice of the characters.

In addition to Berezovsky, Vladimir Putin, Roman Abramovich, Alexander Litvinenko with his wife Marina, Alexander Voloshin, and other faces and shadows of the era appear on the stage. All of them consider themselves patriots of their country. Still, they all express this patriotism differently, leading to conflicts between the characters. None of them emerges as an absolute winner, just as Russia itself does not benefit from these battles.

“Work on the performance began before the Russian invasion of Ukraine, but now some episodes have received a new, even more topical sound. Before rehearsals, we all tried to find out more about the real biographies of our characters. For example, I read the book ‘Death of a Dissident’,” actor Jamael Westman, who played Alexander Litvinenko, told Afisha.London magazine after the performance. He also said that Marina Litvinenko came to the version and thanked the creators and actors.

And what about Berezovsky? A talented mathematician and decision-making psychology theorist, he dreams of a Nobel Prize but, in the end, finds himself in the centre of either a whirlpool that carries him downstream or a web that he weaves. Hollander was able to perfectly capture both the freedom-loving idealism of the hero, his outright cynicism, and periodic flashes of megalomania, but most importantly: his nature as a player who plans the game several moves ahead and at the same time constantly raises the stakes, because he is regularly lucky. But this can’t go on forever…

- Photo: Marc Brenner

- Photo: Marc Brenner

Life begins to give him blow after blow: the voluntary-compulsory exile from his homeland and the sale of business assets; a quarrel with his beloved protégé Abramovich, nicknamed “the Kid” in the play, who has matured and does not recognize the gentlemen’s agreements of the 90s ; and in the end — a kick “in the gut” from the British justice he so reverently loved.

I had the opportunity to cover numerous hearings involving Berezovsky in London courts — from a long and ultimately unsuccessful process for his extradition to the Russian Federation to his endless lawsuits with Russian television, then with former business associates, then with someone else. There was only one thing in common between these trials: Berezovsky invariably won them and was full of compliments to the British justice system. After one of these victories, he made a comment that I still remember: “Not a single day lived in London can be considered lived in vain.” He seemed to feed on energy from these court battles, which helped him restore the sense of justice. Perhaps he hoped that someday a genuinely independent and non-corrupt judicial system would appear in Russia.

Follow us on Twitter for news about Russian life and culture

That is why the loss in the “trial of the century” in 2012, and especially a loss to Abramovich, with the judge’s wording that Berezovsky was “deliberately dishonest” in his testimony knocked him down completely. The last attempt to change the course of fate and return to their homeland is the famous letter to Putin, the existence of which has not yet been confirmed, but Morgan still allows the audience to “read” it.

Photo: Marc Brenner

It is there, almost at the end of the second act, when the narrative finally moves from following the political events to depicting the inner, human drama of the protagonist, which culminates in Vladimir Vysotsky’s Song about a Friend performed by Berezovsky embracing a bottle of vodka. His drunken walk resembles a series of random chess moves on the board, which in the end completely confuse him and lead to the well-known tragic outcome.

“The scene where he says that he was betrayed by a friend, in my opinion as an actor, is a bit underpowered. It could have been made into an even more emotionally strong climax. There must be a catharsis here,” says Belarusian actor Oleg Sidorchik, who narrated the Russian-language fragments of the play, including the nostalgic passage about Russia that opens and ends the show. “But I am generally satisfied with the performance, and he [Morgan] is a good playwright. He makes it look like a drama develops according to the plot, and even a tragedy, but the audience laughs at the text.”

Indeed, in the course of the action, both the Russian-speaking and the British public laugh, and each part of the audience reacts to different “triggers”, but perhaps, only those who regret that history took a wrong turn at some point and went the way of “wrong” patriots would shed some tears.

“Almeida is a small theatre, and all its performances look poignant. Viewers, sitting at arm’s length, seem to be able to touch the story itself and become part of this process. In ‘Patriots’ I especially felt that here it is — life and history, a national tragedy, a cultural disaster. Everything is so close, alive, and sharp that you want to scream… But, as often happens, you become dumb from the inability to believe in your actual reality. You can do almost nothing with it, you just suffocate in emotions, fall to the bottom and take the outcome for granted. There are rumours that the performance may move to the West End, but to see it in the intimate Almeida atmosphere is the highest pleasure,” Margarita Bagrova, Editor-in-Chief of Afisha.London shares her impressions.

But the play is undoubtedly relevant and topical and it is evidenced by the fact that probably for the first time in post-pandemic London, especially during the summer holidays, all tickets for such a show were sold out literally in a matter of days. Now we are waiting for new dates, have time to grab the best places.

● Noël Coward Theater

● May 26 – August 19

Alexander Smotrov

Cover photo: Marc Brenner

Read more:

A short guide to being a happy parent of a happily multilingual child

SUBSCRIBE

Receive our digest once a week with quality Russian events and articles