Ivan Turgenev’s Sojourn in London: a literary ambassador between the Russian Empire and the West

Ivan Turgenev, the illustrious writer, and zealous ambassador of Russian culture in the Western world, achieved global renown during his lifetime. Through his eloquent translations, he introduced Britain to the masterpieces of Pushkin, Tolstoy, and Dostoevsky. Much like his contemporaries, Turgenev indulged in the life of a cosmopolitan dandy. He resided in the vibrant city of London, partook in sumptuous dinners with esteemed members of Parliament, cultivated a cherished friendship with the literary luminary Charles Dickens, and formed an intriguing alliance with the enigmatic exile, Alexander Herzen. Afisha.London magazine illuminates Turgenev’s remarkable journey in popularizing Russian drama throughout Great Britain, culminating in the prestigious conferment of an honorary Doctor of Civil Law from the University of Oxford.

Youth and Introduction to Europe

The future author of popular ‘Mumu’ (a poignant short story about the love between a serf and his dog, cruelly disrupted by the jealousy of his mistress) was born on November 9, 1818, into the Turgenev family, a noble family from Tula, in the Oryol city of Russian Empire. His father, Sergey Turgenev, served in the Imperial Russian Guard Cavalry, which was composed of 93 percent hereditary Russian aristocracy, making him a representative of the elite. Sergey, a carefree cavalry officer, had squandered his entire fortune by the age of 23 and was forced to marry a wealthy 29-year-old landowner named Varvara Lutovinova, known for her domineering and harsh character. Their marriage remained unhappy, despite the birth of three children, with Ivan Turgenev being the second child and his mother’s favourite. It was Varvara who instilled a love for literature in her sons. The Lutovinov estate, Spasskoe-Lutovinovo, housed a vast library, predominantly stocked with French literature. The landowner had a particular affection for the French language, and conversations and even prayers in their household were exclusively conducted in French.

In 1827, the Turgenev family moved to Moscow, opening the path for Ivan to become a renowned writer. At the age of 15, in 1833, Ivan enrolled in the Faculty of Literature at Moscow University, where contemporaries such as Vissarion Belinsky and Alexander Herzen were also studying, destined to become some of the most fervent revolutionary publicists. However, Ivan completed his education in the Northern capital, at the Historical-Philological Faculty of St. Petersburg University. It was during this time that the young Ivan experimented as a poet, writing verses, and translating the works of British classics like Byron and Shakespeare into Russian.

Read also: The last Stroganov: how Hélène de Ludinghausen revived a lost Russian legacy

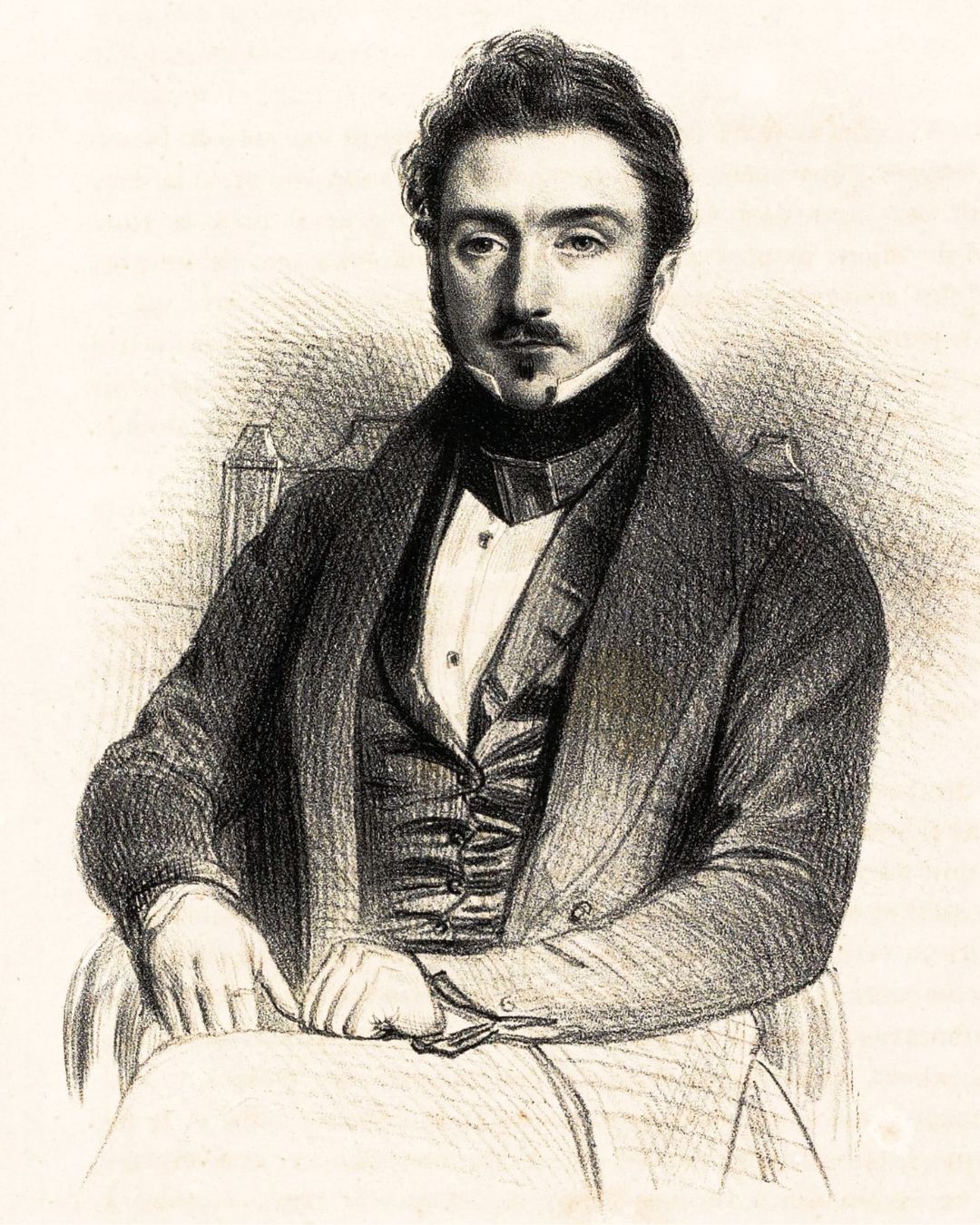

- Portrait of Ivan Turgenev by Gorbunov (1838). Photo: Wikipedia

- Portrait of Ivan Turgenev by Eugène Lami (1843-1844). Photo: Wikipedia

By 1837, Ivan had accumulated over a hundred poems, and after graduating from the university, he embarked on a journey to Berlin to continue his studies. The doors of the University of Berlin opened to him, where he attended lectures on Greek and Roman literature, studied Latin, and read classical texts in their original language. The Western European lifestyle left an indelible impression on Ivan, and with youthful idealism, he aspired to introduce a piece of what he had experienced into Russian culture. In 1840, he returned to Europe, visiting Italy and Austria and, in Germany, serendipitously encountering a beautiful Jewish girl in a Frankfurt pastry shop. He fell in love with her, and their love story would later serve as the basis for his novella “Torrents of Spring”.

Фото: Afisha.London / Midjourney

Trips to London and the Struggle for the Abolition of Serfdom

The autumn of 1843 marked a turning point in the life of 25-year-old Turgenev. It was on the stage of the opera theatre in St. Petersburg that he first laid eyes upon the young but already globally renowned Spanish French soprano, Pauline Viardot. Turgenev’s contemporaries attest that Viardot may not have possessed conventional beauty, but she captured Ivan’s heart with her charisma, impassioned temperament, and musical talent. Turgenev once confessed:

‘From the very moment I first saw her, I belonged entirely to her, like a dog to its master’.

He was known as an enviable suitor—a handsome giant standing over 6 feet tall, wealthy, well-educated, and already distinguished in exclusive circles. His life had seen its share of vivid but short-lived romances. However, his love for Viardot endured for four decades. After their fateful encounter, Turgenev journeyed to Paris to be with his beloved, undeterred by the fact that Pauline was married. In an unusual turn of events, Turgenev formed a close friendship with Pauline’s husband, Louis Viardot, the director of the Italian Theatre in Paris. The Viardot family provided financial support to the writer when he left Russia against his mother’s wishes, leaving him penniless but for the royalties from his book.

Read also: Felix Yusupov and Princess Irina of Russia: love, riches and emigration

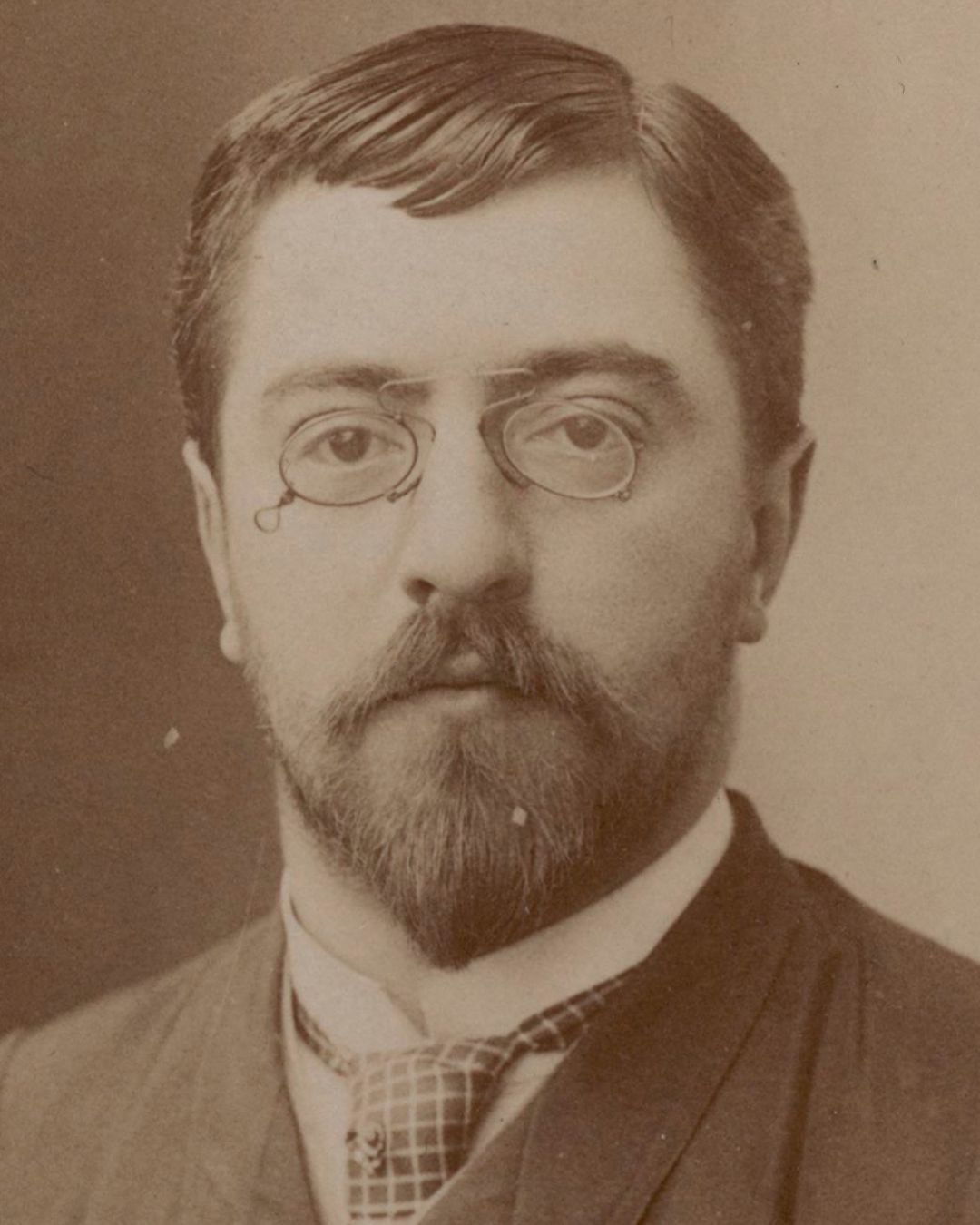

- Pauline Viardot by Carl Timoleon von Neff (1842). Photo: Wikipedia

- Portrait of Louis Viardot by Émile Lassalle (1840). Photo: Wikipedia

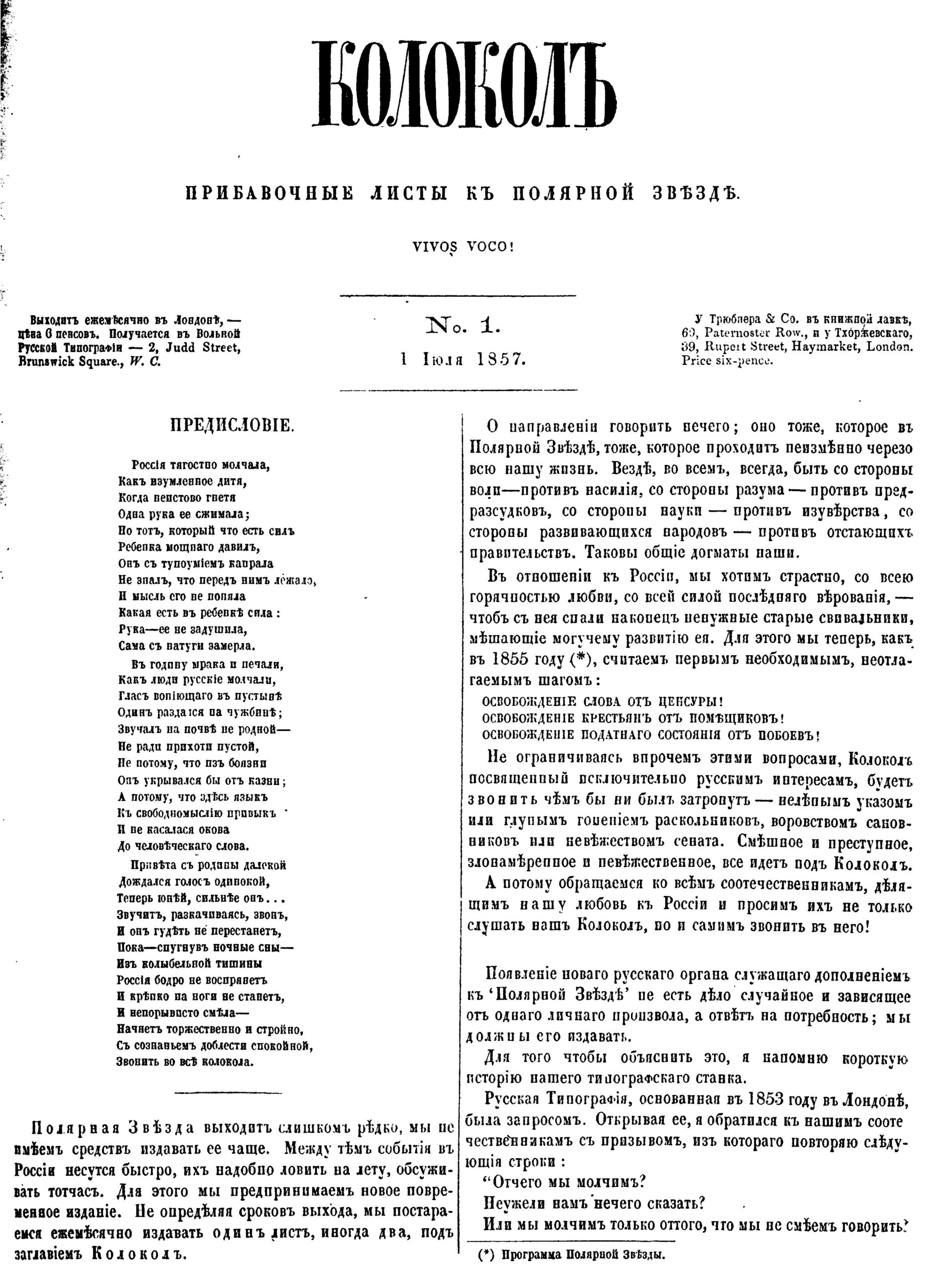

When Viardot travelled, the writer had support from Alexander Herzen, who had permanently left Russia for Paris by 1848. In that same year, both witnessed the February Revolution in France, which horrified them due to the subsequent repression of the workers. Disillusioned by the ideals of bourgeois revolutions and their shared love for their homeland, the writers were drawn closer together, leading to their collaboration on the first Russian political newspaper, ‘The Bell,’ which Herzen began publishing in London in 1857.

- The first page of the first issue of Kolokol (1857). Photo: Wikipedia

- Herzen House on 1 Orsett Terrace. Photo: Spudgun67, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

In the 1850s, Turgenev returned to Russia and was arrested after his publication of an obituary for Gogol in the ‘Moscow Gazette,’ a time when Gogol’s works were not held in high regard. The government under Nicholas I also harboured concerns about the writer’s trips abroad and his radical views on serfdom. In 1857, when he was granted the opportunity to travel to Europe again, Turgenev headed to London, where the charming writer immediately found like-minded companions. He recalled his first visit, saying:

‘I was in England, and thanks to two or three fortunate letters of introduction, I made many pleasant acquaintances, among whom I will mention only Carlyle, Thackeray, and Disraeli.’

British historian and writer Thomas Carlyle hailed ‘Mumu’ as the best story he had ever read and welcomed the writer into his home. In 1858, Turgenev visited London again as an honorary guest of the English Literary Fund Society and met another British legend, the realist writer Charles Dickens, with whom he developed warm and friendly relations. Turgenev presented the French edition of his series of stories, ‘Sketches from a Hunter’s Album,’ to Dickens with a dedication: ‘To Charles Dickens from one of his greatest admirers.’

Read more: Leo Tolstoy in London: shaping the british literary landscape

Both ‘Mumu’ and ‘Sketches from a Hunter’s Album’ dealt with the issue of serfdom in 19th-century Russia. Through these works, Turgenev shed light on a global problem that had been seldom discussed publicly before. The prototypes of the characters in his stories were drawn from real episodes from the writer’s childhood and youth, which he had observed in his mother’s house. Her despotism and heavy-handedness extended not only to serfs but also to her own children. Before Turgenev, no one had depicted serfs as individuals deserving freedom and respect. For this, he received recognition in Belinsky’s circle, and the issue of serfdom became the hottest topic during literary gatherings at the renowned London residence of Herzen on Orsett Terrace, No. 1.

Фото: Afisha.London / Midjourney

Starting in 1857, Turgenev became a constant and most active correspondent for ‘The Bell.’ He collected materials, prepared them for publication, and sent them to London. Additionally, the writer developed projects and collective letters advocating for the abolition of serfdom addressed to Tzar Alexander II. He served as the link between Herzen and those correspondents in Russia who were reluctant to acknowledge the disgraced London emigrant. In 1861, serfdom was abolished, after which the writers’ views on Russia’s future significantly diverged. They ceased their collaboration, as Herzen envisioned further development towards peasant socialism, while Turgenev advocated for the unity of historical development for all countries and tried to convince Alexander II of his fidelity to this path.

Turgenev’s Influence on British Literature

In 1863, Turgenev reunited with his beloved Pauline Viardot and her husband in Baden-Baden. Surprisingly, their love triangle continued to thrive successfully, and some biographers even attribute the paternity of Paul’s son, the child of Pauline and Louis, to the writer. By that time, the prosperous writer was spending vast amounts on the Viardot family, and in 1874, he purchased a house and park for them in Bougival, a suburb of Paris. As Turgenev poetically confessed, he never experienced his own family happiness and spent most of his life “on the edge of someone else’s nest.” Perhaps, this is why the protagonists of his novels often suffer in love. Against the backdrop of the generalized image of Turgenev’s female characters emerged the archetype of the “Turgenev heroine.” This archetype is far from romantic and is not adapted to life, but rather, a withdrawn yet strong-willed young woman capable of self-sacrifice and all-consuming love for a weaker male character.

Read also: Leo Tolstoy in London: shaping the british literary landscape

- Paul Viardot (1910). Photo: Wikipedia

- Фото: Afisha.London / Midjourney

Amid the societal changes taking place, the writer depicted the new people of the 1860s in his novel “Fathers and Sons.” These were nihilists who rejected social prejudices but were only capable of destruction rather than creation. Turgenev became the most fashionable writer in Europe for a time. He provided consultations, edited, and translated the novels of Russian writers into European languages and vice versa. In Baden-Baden, the writer actively promoted Russian culture and corresponded with prominent European authors such as Emile Zola, Charles Dickens, Guy de Maupassant, Victor Hugo, and many others. His contribution to strengthening cultural ties between Russia and the West cannot be overstated.

Read more: Dostoevsky in London and his influence on the British classics

In the United Kingdom, Turgenev was the first writer to introduce the greatness of the Russian novel. As literary critic Tatiana Krasavchenko noted in her article “The Perception of I. S. Turgenev in Britain,” the British perceived Turgenev as a “strong and energetic writer,” though after the emergence of Tolstoy and Dostoevsky, he was relegated to the status of an “aesthete” and “pure artist.” However, Turgenev truly gained recognition in Britain after his death when, between 1894 and 1899, Constance Garnett translated his novels, plays, stories, and poems into English. Thanks to her, the British also learned about Tolstoy, Chekhov, and Dostoevsky.

A new generation of novelists in the late 19th to early 20th centuries became interested in Turgenev’s works, driven by the growing fascination with psychological analysis, inspired by Sigmund Freud. Turgenev became a central figure for the creativity of John Galsworthy, the author of “The Forsyte Saga,” who was inspired by Turgenev’s profound examination of feelings and emotions. English playwright Arnold Bennett found in the works of the Russian classic “tranquil and exquisite soft beauty,” while Anglo-Irish writer George Moore described Turgenev as a master capable of skilfully reproducing life.

Фото: Afisha.London / Midjourney

In October 1878, Turgenev visited Cambridge, causing a sensation among the college students. On June 18, 1879, he received an honorary Doctor of Civil Law degree from the University of Oxford. The Russian classic became the first belletrist to receive such an honour, which had previously been reserved for diplomats, theologians, and political figures. At the solemn ceremony held in the university theatre, Turgenev received the loudest applause. In the same year, the writer established several significant acquaintances. At the Reform Club on Pall Mall Street, he dined with politician George Shaw Lefevre and conversed with the yet unrecognized great poet and artist William Blake.

An interesting moment: as part of his visit to Cambridge and its surroundings, Turgenev later had the opportunity to visit Newnham College in the company of Millicent Fawcett, the wife of the parliamentarian Henry Fawcett. Founded in 1871, Newnham College is considered the first women’s college led by women. Later, Turgenev bitterly confessed to Millicent Fawcett, “What I wouldn’t give to see such educational institutions for women in my homeland!”

From his travels in England, Turgenev brought back impressions of the English as a practical and original people, though he often lamented the high cost of living in London. The twilight of the writer’s life marked the peak of his success in both Europe and Russia, but it was overshadowed by a serious illness. Until his last breath, his devoted Pauline served as his caregiver. On September 3, 1883, Turgenev passed away in Bougival, and the news of his death stunned his admirers, with over 400 people participating in the funeral procession through Paris. According to the writer’s will, he was buried in the Volkov Cemetery in St. Petersburg, Russia.

Read also: Emigration of the Romanovs to Great Britain: the story of Grand Duchess Xenia

- Tombstone of Turgenev at Volkovskoe Cemetery. Photo: Wikipedia

- Turgenev’s dacha in Bougival, where he died. Now there is a museum here. Photo: Wikipedia

Turgenev’s imposing figure remains one of the most significant in world culture. In 2018, UNESCO included his name in the list of commemorative dates, recognizing him as a genius, a defender of human rights, and a humanist who was ahead of his time.

Cover photo: Afisha.London / Midjourney

Read more:

Composer Alexander Scriabin: a journey from earthly melodies to celestial aspirations

Bakst, Benois and Dobuzhinsky: How an Extensive Collection of Russian Art Ended Up in Oxford

The London Christmas Guide 2025: shows, skating and sparkling nights

SUBSCRIBE

Receive our digest once a week with quality Russian events and articles