Composer Alexander Scriabin: a journey from earthly melodies to celestial aspirations

As the 19th century transitioned into the 20th, Russia was experiencing an era of profound complexity. It was a time marked by an unsettling blend of societal decay and a hopeful yearning for the renewal of life. Emblematic of this hope was Alexander Scriabin, a visionary composer who emerged with a message: humanity was endowed with strength and grandeur. Proclaiming himself the architect of a new world, Scriabin harboured aspirations of elevating mankind through “The Mysterium” — an ambitious ceremonial event planned for a custom-built temple in India. Here, he envisioned that all ethnicities would unite, magnetised by a divine illumination. Tatiana Efimova, a musicologist, and columnist for Afisha.London, explores the facets of Scriabin’s extraordinary life and creative journey, and delves into the ultimate outcome of his audacious vision.

Early Life and the Genesis of Musical Talent

Born on December 25, 1871 — on the day of the Catholic Christmas — Scriabin discerned a mystical significance in this synchronicity, believing it to be a cosmic indicator of his life’s trajectory. He displayed prodigious musical talents from a tender age, effortlessly capturing melodies by ear and improvising on the piano. In adherence to family traditions — given that his father and grandfather were military men — Scriabin was initially enrolled in the Second Moscow Cadet Corps. However, his physical frailty soon revealed that a military career was untenable. Opting for a musical path instead, he entered the conservatory and distinguished himself by graduating with a gold medal.

From the outset of his career, Scriabin captivated audiences with his exceptional artistry at the piano. Unlike his contemporary Sergei Rachmaninov, Scriabin chose to perform solely his own original works — ranging from mazurkas and preludes to sonatas. His burgeoning reputation soon attracted the attention and support of philanthropist Mitrofan Belyaev. Bolstered by this patronage, Scriabin was able to publish his groundbreaking compositions and undertake concert tours throughout Europe.

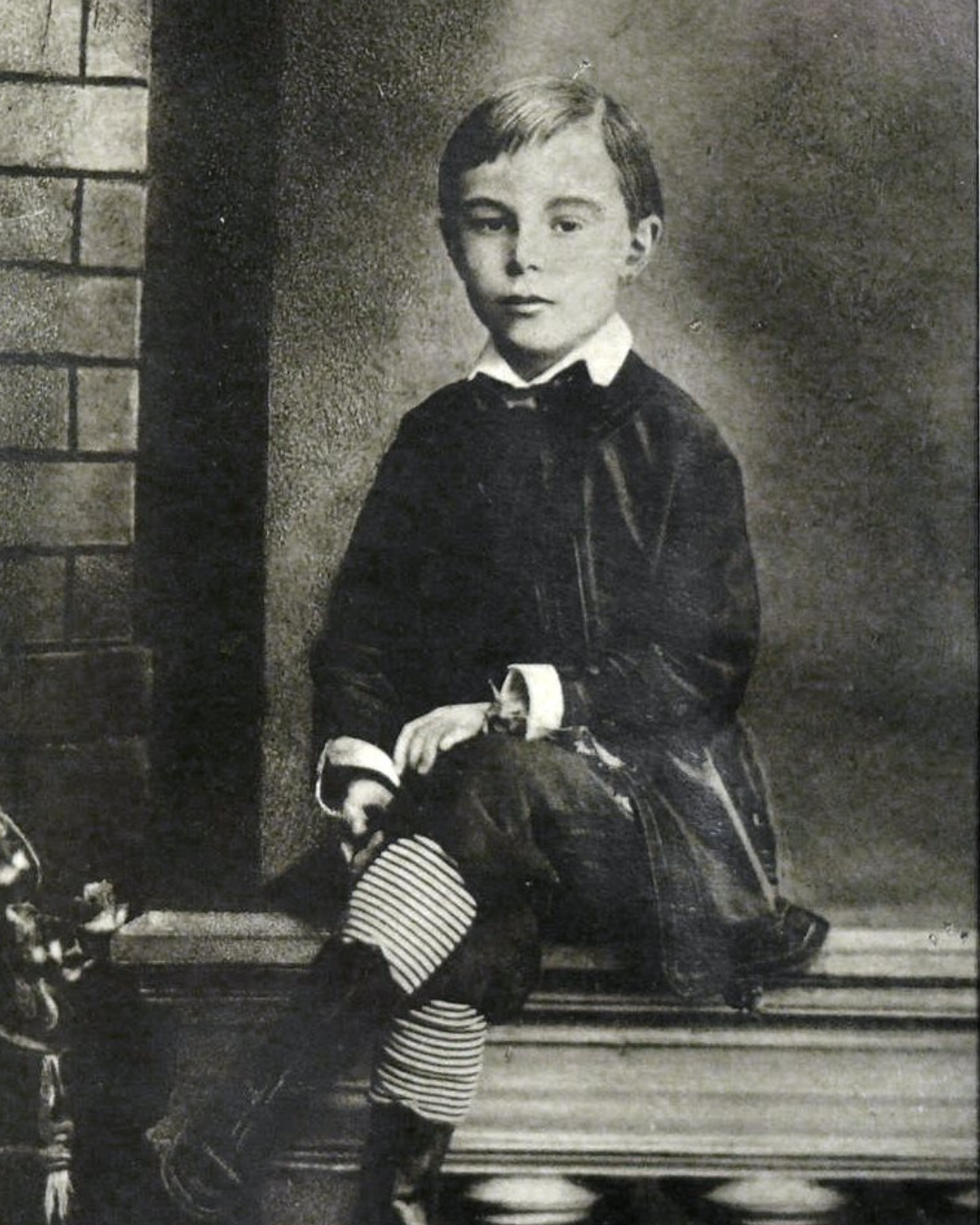

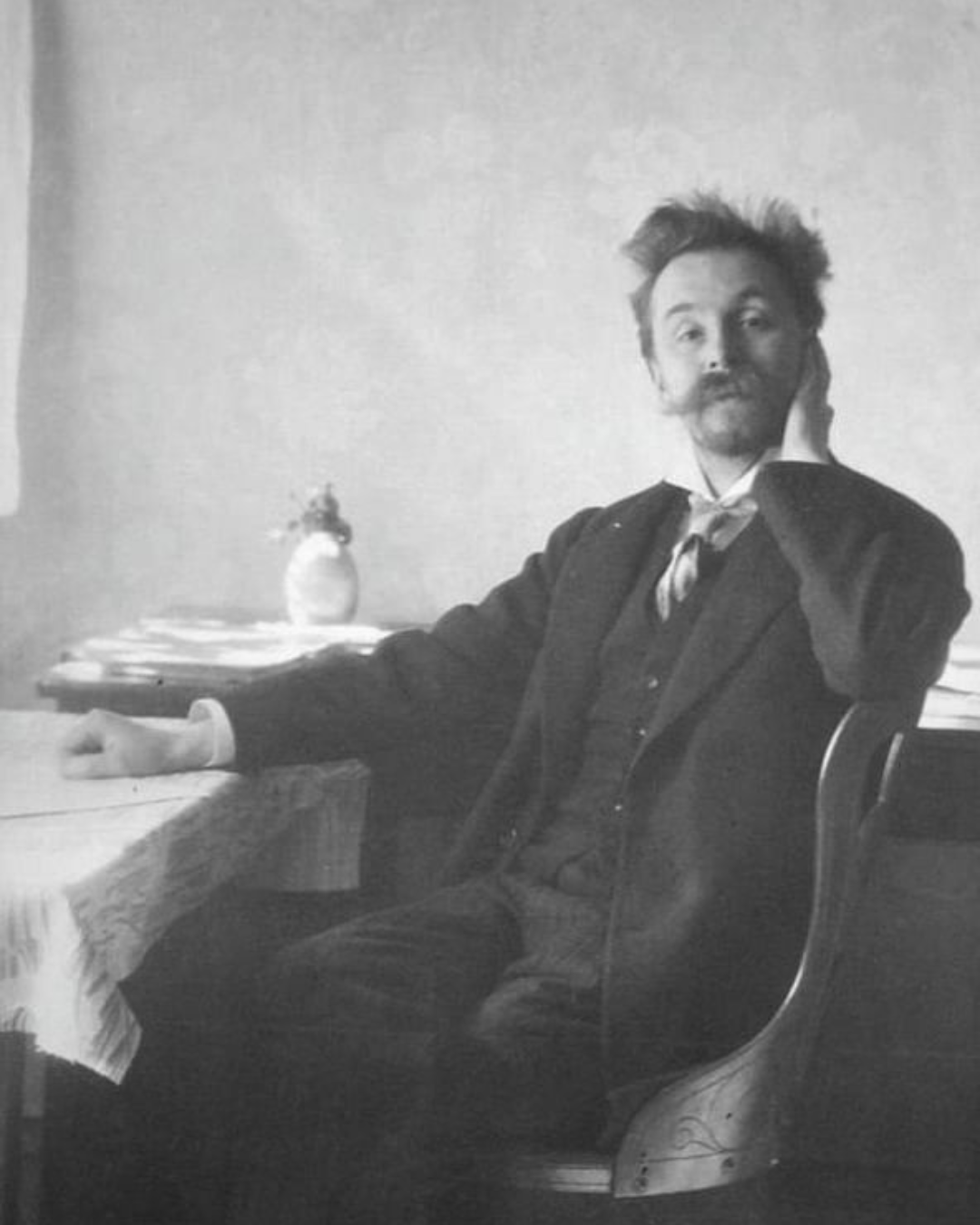

- Young composer, 1897. Photo: Wikipedia Commons

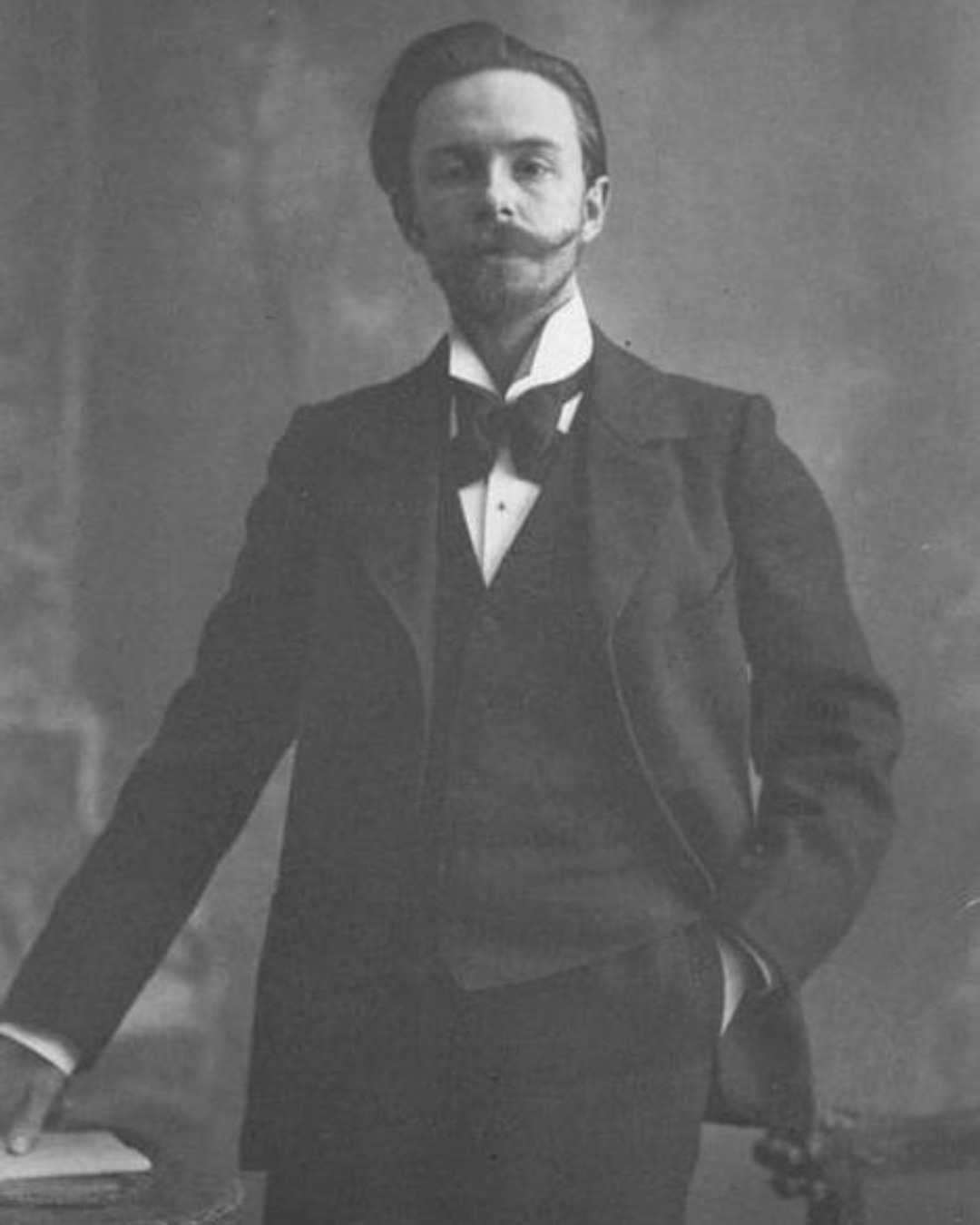

- Alexander Scriabin, 1902-1903. Photo: Alexander Scriabin Memorial Museum

The Evolution of a Creative Identity

Entering the 20th century with a profound sense of self-purpose, Scriabin felt empowered to diverge from well-trodden paths. From the outset, his symphonic works were notable for their intricacy and grandiosity. His First Symphony, comprising six movements, incorporated a choir that celebrated the transformative power of art. Meanwhile, his Second Symphony, structured in five movements, was remarkable for its complexity.

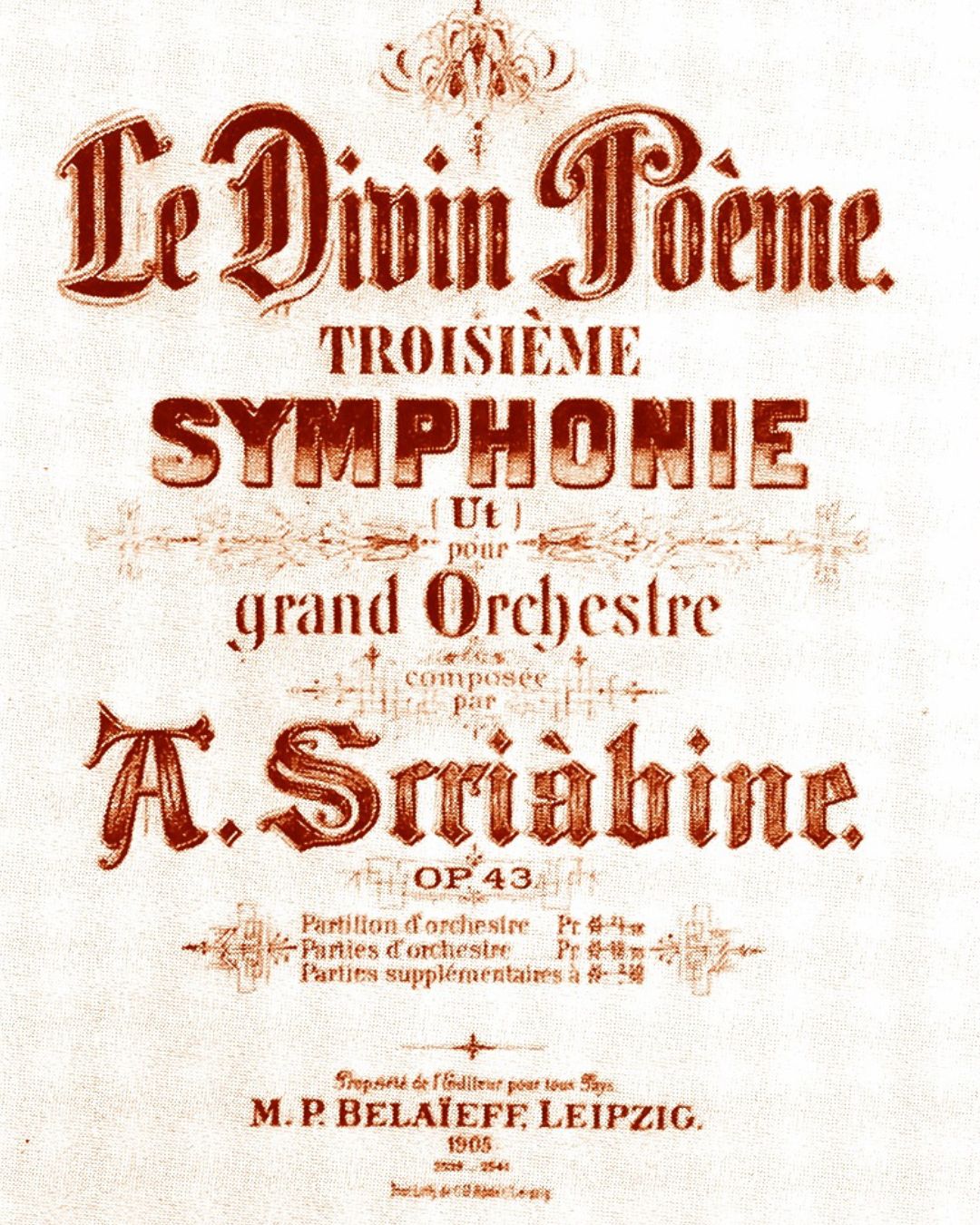

In 1904, Scriabin travelled to Switzerland where he engaged deeply with the philosophies of Kant and Hegel, as well as Buddhist treatises and mystical doctrines. It was during this period that he completed his Third Symphony, which he dubbed “The Divine Poem”. This work encapsulated the composer’s core ideas — overcoming worldly temptations, concerns, and anxieties, and elevating the human spirit towards a realm of light and beauty. Scriabin continued to expand on these themes in his subsequent compositions, assigning them poetic titles such as “The Poem of Ecstasy”, “The Winged Poem”, and the poem “Towards the Flame”.

“I am the creator of another world”, Scriabin asserted about himself. Having become a mystical romantic, he opted to dwell predominantly in an imaginary realm, one he rarely allowed others to enter.

Light and Music

In 1910, Scriabin reached a pinnacle in his creative journey with his composition “Prometheus: The Poem of Fire”, scored for orchestra, organ, piano, and choir. To visually embody the fiery persona of Prometheus, who leads humanity towards a realm of light and beauty, Scriabin integrated a part for a “light-music keyboard” into the score. This was intended to accompany the music by projecting vivid bursts of colour.

- “The Divine Poem”, title page of the first edition, 1905. Photo: Wikipedia Commons

- Scriabin after finishing “Prometheus”, 1910. Photo: Alexander Moser / Alexander Scriabin Memorial Museum

Scriabin had a unique connection with colour; he experienced chromesthesia, a form of synaesthesia where certain musical tones or keys evoke colour associations. Other composers like Franz Liszt, Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, and Olivier Messiaen also shared this trait. Unfortunately, due to technical difficulties, the premiere of “Prometheus” at the Great Hall of the Moscow Conservatory took place without the intended colourful accompaniment. However, a home performance was made possible thanks to Scriabin’s friend, the engineer Mozer, who constructed a special colour-light device, assigning a distinct colour to each musical note.

Read more: Composer Pyotr Tchaikovsky in London: impressions, recognition and success

Attempts to fully realise Scriabin’s vision in large concert halls were only accomplished after his death— in 1915 in New York and in 1916 in London and Moscow. Could the composer have ever imagined that a century later, we would delight in light-music shows that embody the synthesis of the arts he had envisioned? Such shows captivate a broad audience for good reason: by stimulating our senses, light-music arouses our imagination and immerses us into a magical realm where we are not merely passive spectators but become active participants in the performance.

The Mysterium

Scriabin believed in the transformation of humanity and devoted the last 15 years of his life to composing “The Mysterium”, a monumental work intended to be performed by all of humanity in a specially constructed temple in India. He envisioned “The Mysterium” as a seven-day sacred rite, during which music, combined with light effects, aromas, and expressive movements, would lead to a state of catharsis.

Regrettably, the grand vision of the composer was never to be realised. Scriabin passed away suddenly on 14th April 1915 due to blood poisoning caused by a carbuncle on his lip. In a poignant twist of fate, while his relatives were sorting out the extension of his apartment lease, they were stunned to discover that Scriabin had signed a three-year contract, the end date of which coincided precisely with the day of his funeral.

Read more: Rudolf Nureyev: an emigrant, who became a ballet legend

This remarkable detail adds a layer of complexity to the narrative of Scriabin’s unrealised ambitions and dreams, making his story even more compelling and poignant.

Where to hear Scriabin’s music in London?

The composer’s works are still beloved by listeners today. Scriabin’s music can be heard on 12 October performed by pianist Anthony Hewitt, on 25 October selected compositions will be performed by pianist Beatrice Rana, and on 3 December the London Symphony Orchestra will play “The Poem of Ecstasy”.

Tatiana Efimova text/Margarita Bagrova translation

Cover photo: Afisha.London / Midjourney

Read more:

How Diaghilev’s “Saisons Russes” influenced the European art world of the 20th century

Bakst, Benois and Dobuzhinsky: How an Extensive Collection of Russian Art Ended Up in Oxford

Dostoevsky in London and his influence on the British classics

SUBSCRIBE

Receive our digest once a week with quality Russian events and articles