Exploring Malevich: Locations and Insights into His Revolutionary Art

What do you know about Kazimir Malevich? You are undoubtedly familiar with the “Black Square,” and the debates it continues to stir among art connoisseurs to this day (and it’s over a hundred years old!). The artist challenged the universal understanding of painting by creating an entirely new movement—Suprematism. We shouldn’t merely reproduce what we see on the canvas; true creativity must be conjured from scratch—Malevich paid a price for this revolutionary idea at the time, yet he also produced paintings that many could understand. But let’s take it step by step. The magazine Afisha.London discusses the creative journey of the artist from Kyiv, the challenges he faced, and where his paintings can now be viewed.

Ukrainian Period

Kazik, as his parents called him, was born in 1879 in Kyiv into the family of a sugar industry worker. Due to his father’s job, they moved frequently and lived mainly in the rural Ukrainian countryside. The future artist discovered his love for drawing in Konotop, and he fondly remembered his life in this town throughout his life:

“Oh, glorious city of Konotop! It was all gleaming with lard. At the markets, rows of aunties selling lard sat at tables, from whom the smell of garlic emanated. Piles of various kinds of lard were heaped on the tables.”

Once, his father took Kazik with him to the annual sugar refiners’ fair in Kyiv, but instead of becoming immersed in his parent’s trade and following in his footsteps, the boy was impressed by the picturesque canvases. Despite his father’s disapproval, he continued to draw and at the age of 17 enrolled in the Kiev Drawing School of the artist Nikolay Murashko, where he studied for a year.

Art of Kazimir Malevich in The Amsterdam City Stedelijk Museum. Photo: Afisha.London

Poverty and Despair

In 1896, the family faced another relocation—this time to Kursk. There was a catastrophic lack of money, and young Kazimir found work as a draughtsman at the Moscow-Kursk railway office, continuing to draw in his free time. He realized that he lacked academic education and contemplated moving to Moscow: it seemed that was where all the money and great artists were.

- “Landscape with Yellow House” (1907), Photo: Russian Museum

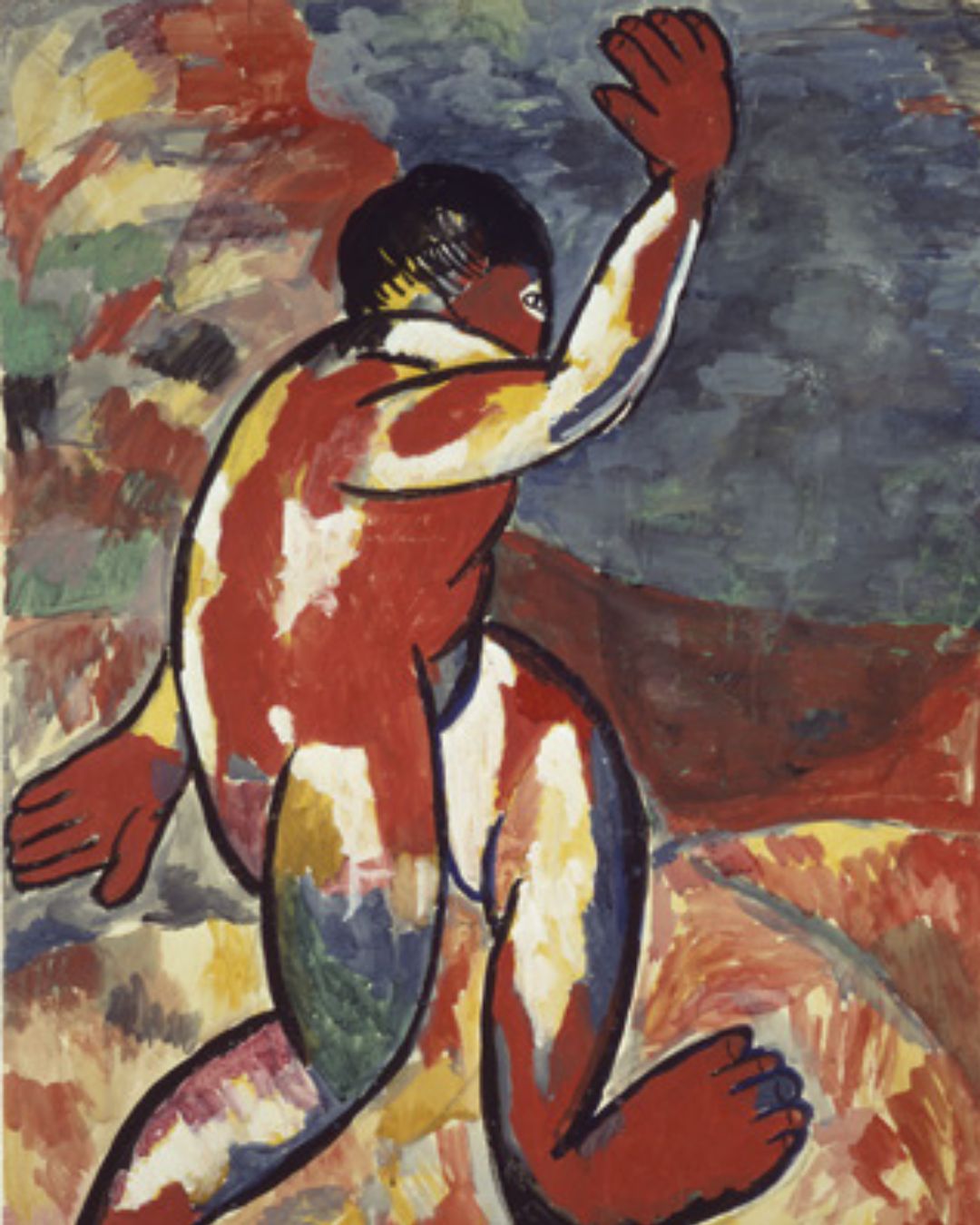

- “Bather” (1911). Photo: © 2024 Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam

Malevich tried to enter the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture three times, each time unsuccessfully. However, he did not give up on the idea of living in this city and finally moved there in 1907, beginning to attend the school-studio of Fyodor Rerberg. Kazimir began searching for his artistic identity, mimicking the drawing styles of various masters: for example, in the style of the impressionists, he created “Landscape with a Yellow House (Winter Landscape),” and his first avant-garde paintings were drawn in 1910—thus appeared “Bather,” “Gardener.” Inspired by memories from his childhood, Malevich created his first peasant series, deliberately enlarging, distorting, and simplifying the figures of people—this is clearly visible in the paintings “Peasant Woman with Buckets and Child,” “Harvesting Rye.” Even here, one can notice how parts of the body resemble geometric figures.

- “Peasant Woman with Buckets and a Child” (1912). Photo: © 2024 Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam

- “Taking in the Harvest” (1911). Photo: © 2024 Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam

Revolution in Art and Persecution by the Authorities

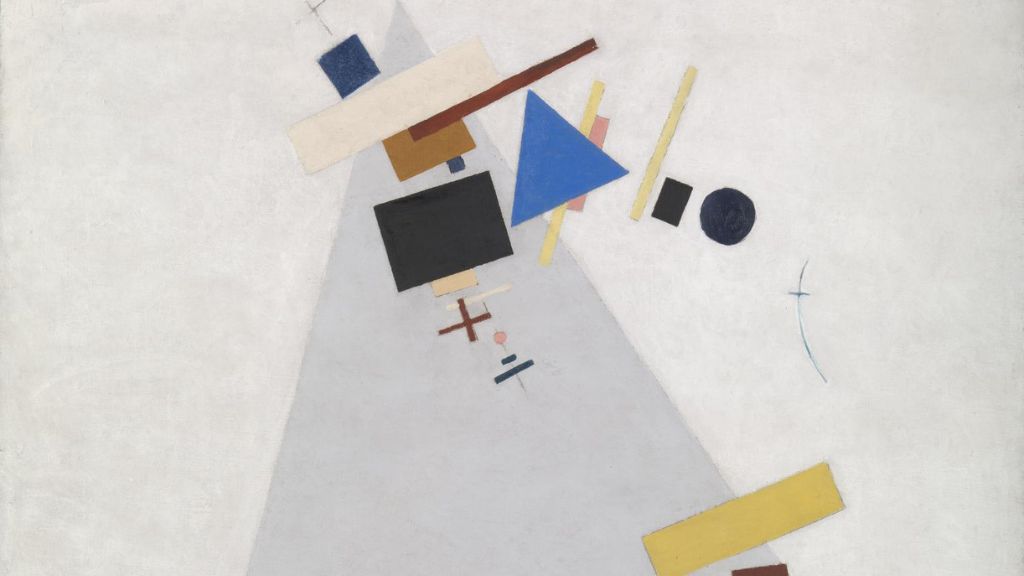

Malevich’s experiments led him to the St. Petersburg creative association of Russian avant-gardists, the “Union of Youth.” At the same time, he created the painting “Cow and Violin” (notably, not on canvas but on a shelf of an étagère, as there was simply no money for quality materials), discovering the style of “alogism” and protesting against the traditional logic of art. The painting combines seemingly incompatible entities: a cow and a violin. Together with poets Velimir Khlebnikov and Alexei Kruchenykh, the artist developed the movement of Suprematism and outlined its principles. Malevich proclaimed a transition to a new non-objective creativity, where color was paramount: the artist should not copy what he sees but must create his own artistic worlds from scratch. He based this on three figures—square, cross, and circle—and built all subsequent paintings in this style upon them. Malevich believed that this was the “healthy form of art,” which could not be simply liked or disliked.

- “Cow and Fiddle” (1913). Photo: Russian Museum

- “Suprematic Painting” (1917). Photo: Afisha.London

All this time, the future star of world art had neither money nor fame, and the situation changed only in 1915. However, he gained notoriety in a scandalous way: 39 Suprematist works were exhibited in St. Petersburg, with the main exhibit being the “Black Square,” hung diagonally in the corner of the room like an icon. This audacity brought him fame in Europe but also triggered a series of persecutions in the USSR.

Soviet art took an anti-avant-garde course, making it increasingly difficult to develop revolutionary ideas. In 1927, the artist visited Europe for the first and last time for an exhibition of his own paintings. Upon returning to the USSR, he was accused of espionage and even arrested for three weeks. Although Malevich continued to create and even exhibit his work, the persecution against him only intensified, and after another exhibition of his work in 1930, he was arrested again—this time for anti-Soviet propaganda. It is believed that these three months in prison seriously undermined his health.

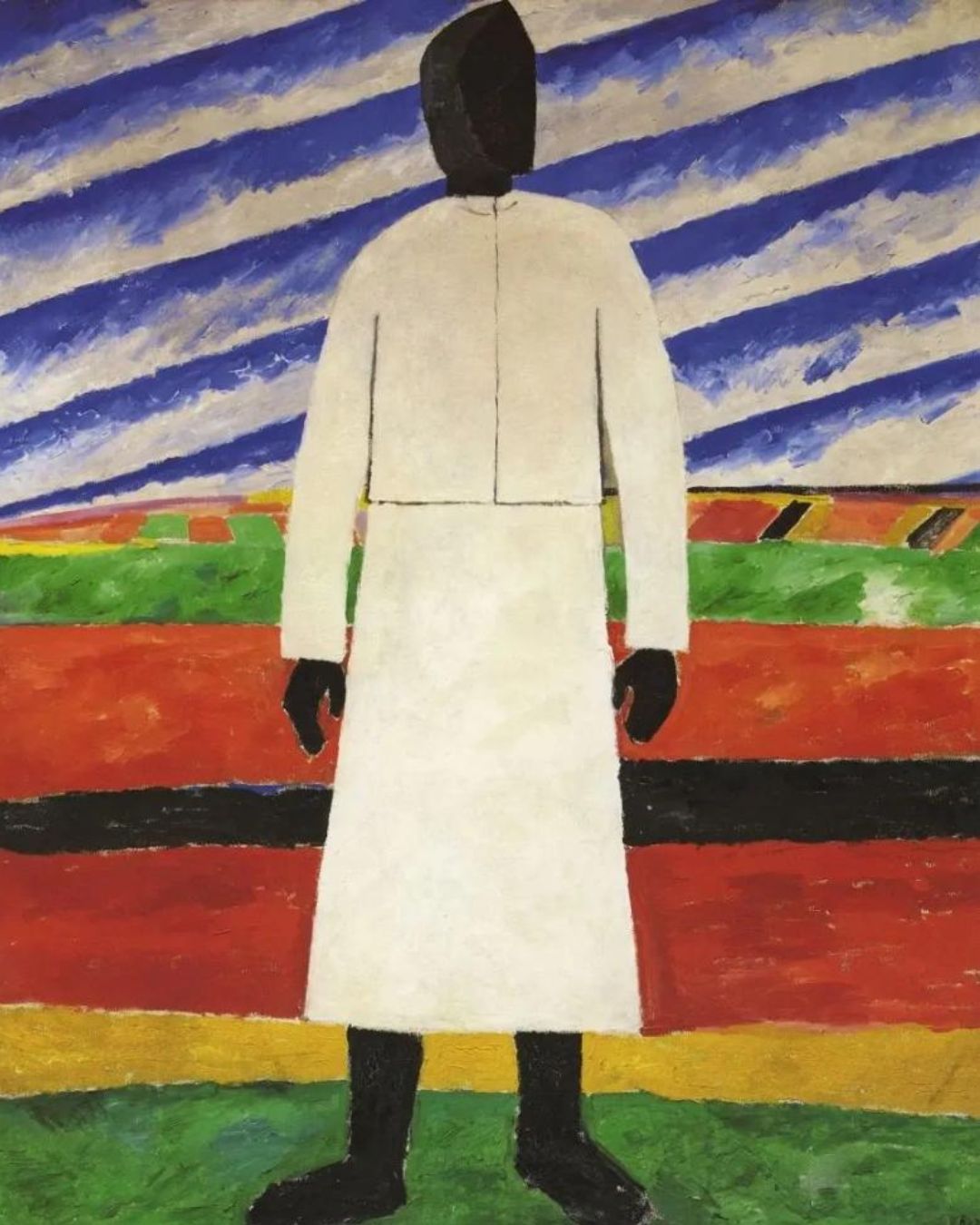

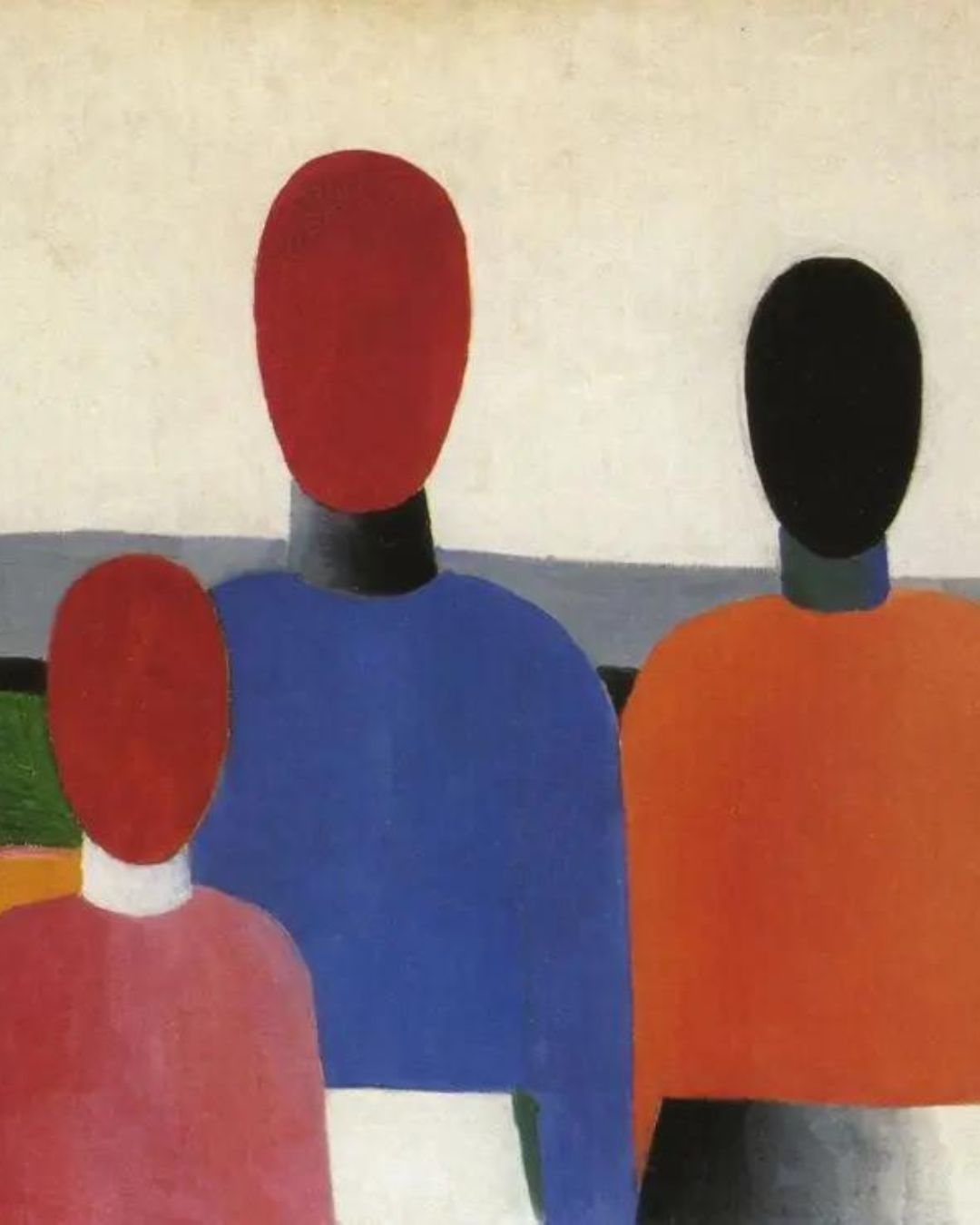

- “Peasant Woman” (1930). Photo: Russian Museum

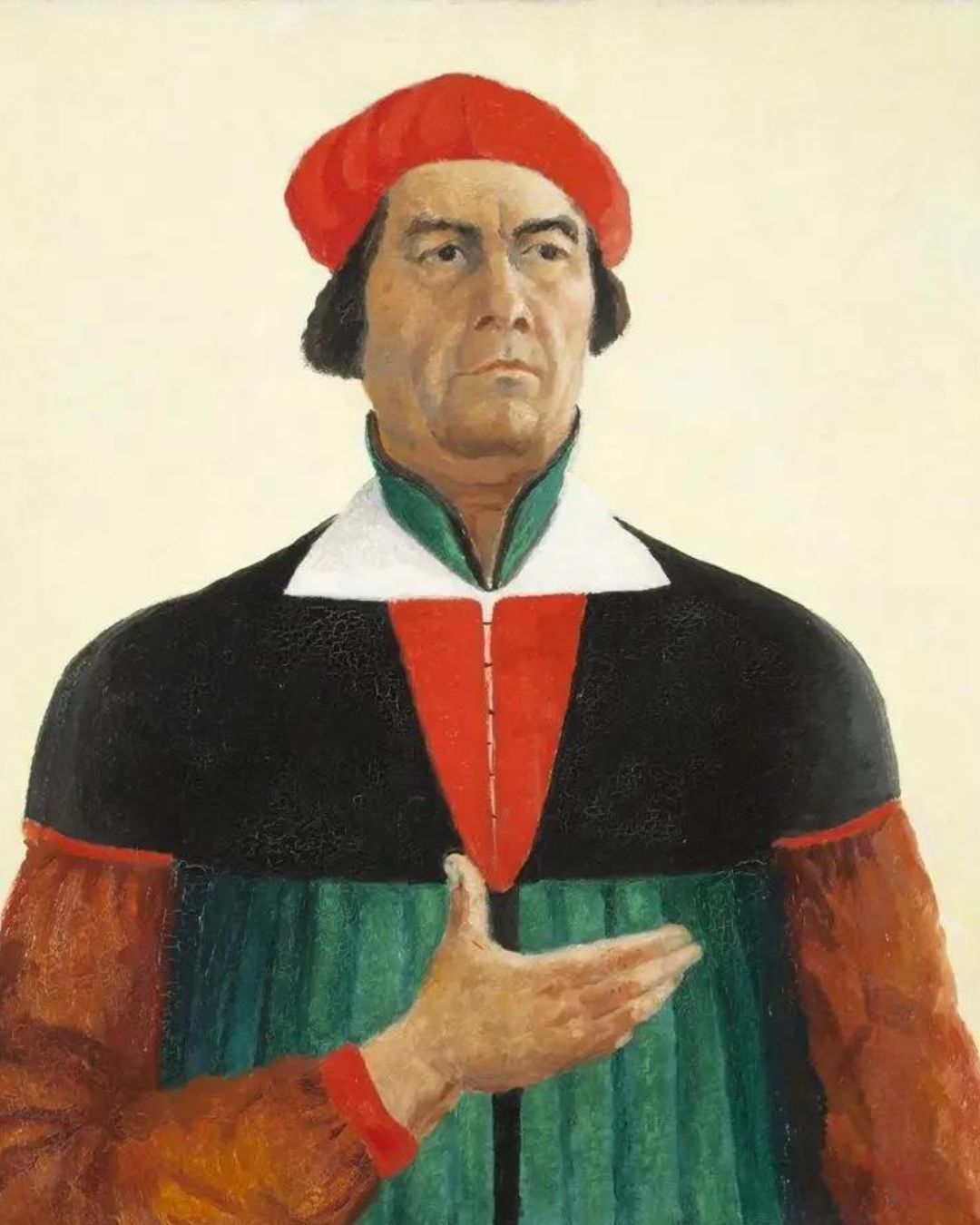

- “Portrait of Artist s Wife N.A. Malevich” (1933). Photo: Russian Museum

After his release, Malevich painted in a post-Suprematist style, depicting peasants without faces, and he even signed one of his works as follows: “The composition is made up of elements, sensations of emptiness, loneliness, and the hopelessness of life.” Shortly before his death, the artist painted a great number of portraits, including a portrait of his wife, Natalia Malevich, and a “Self-Portrait.” Kazimir Malevich died in 1935 at the age of 56, and his ashes are buried in the village of Nemchinovka near Moscow.

Where is Malevich’s artworks?

London

Unfortunately, the British capital cannot boast a collection of the artist’s works, although in 2014 there was a large exhibition at Tate Modern, where even two versions of the “Black Square” were displayed (Malevich created four such canvases in total, — Ed. note). This gallery also houses the painting from 1915-1916 “Dynamic Suprematism (Supremus 57).”

“Suprematism” (1916). Photo: © 2024 Tate Images

Amsterdam

On the other hand, there is a rich collection of Malevich’s paintings in the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, which is a great reason to plan a trip from London by train. How did about two hundred of the artist’s works end up here? The repressions of the 1930s are to blame: Malevich entrusted all his works from the European exhibition to the German architect Hugo Häring and then left for Leningrad. Some of them remained in the collection of the Dutch museum, and now it houses, for example, the aforementioned “Peasant Woman with Buckets and Child,” “Harvesting Rye.”

Paris

Another city where you can take a weekend train trip to see Malevich’s works, but you will need to visit two places. The National Centre for Art and Culture Georges Pompidou houses two of the master’s works: “Running Man” (1933) and “Five Figures with Sickle and Hammer” (1930). Four more paintings are located in the Museum of Modern Art of the City of Paris, featuring not only his later creations but also earlier periods: “Black Square and White Tubular Shape” (1915), “Study for a Peasant Portrait” (1911).

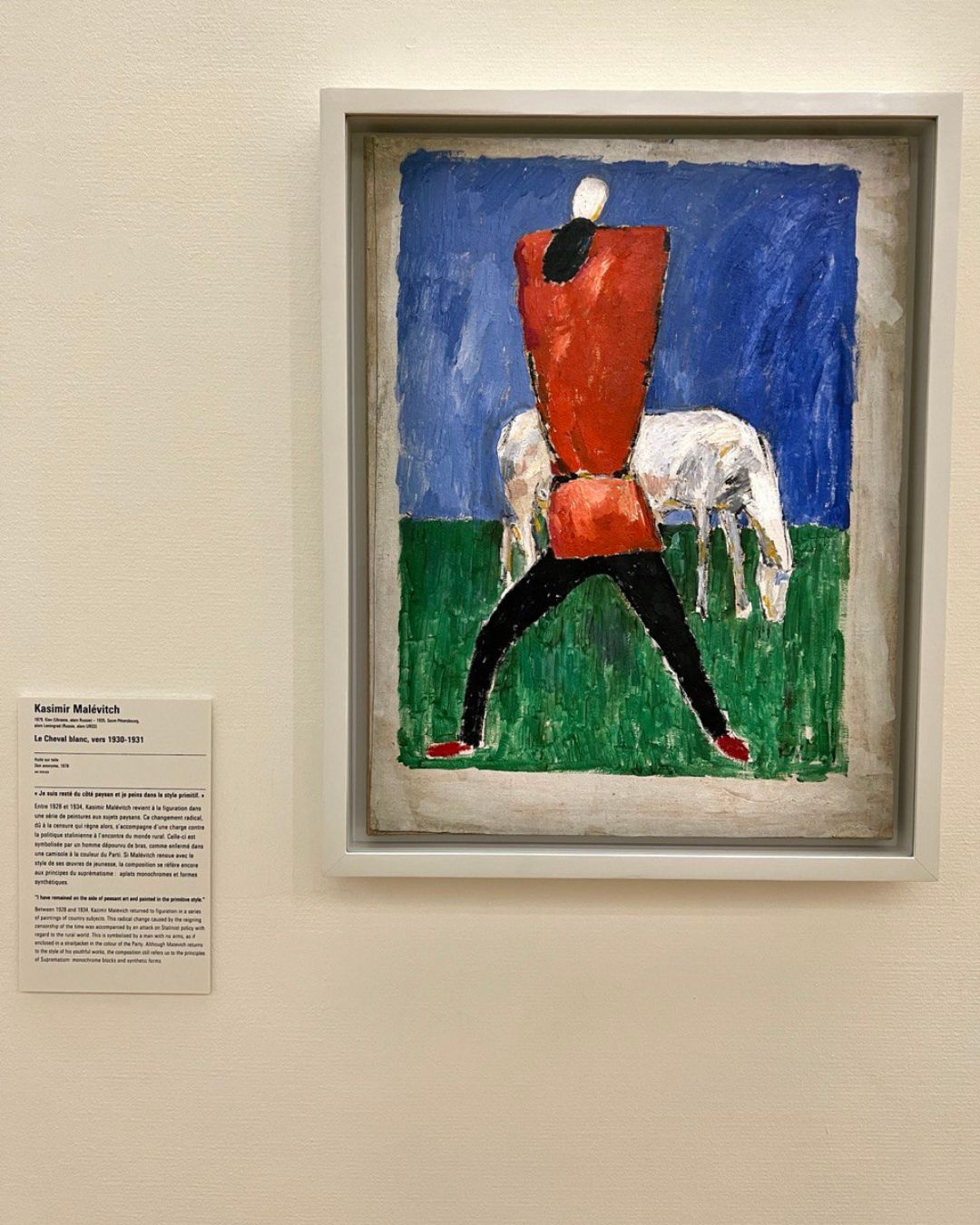

- “The Running Man” (1933). Photo: Afisha.London

- “Man with horse” (1932). Photo: Afisha.London

Ukraine

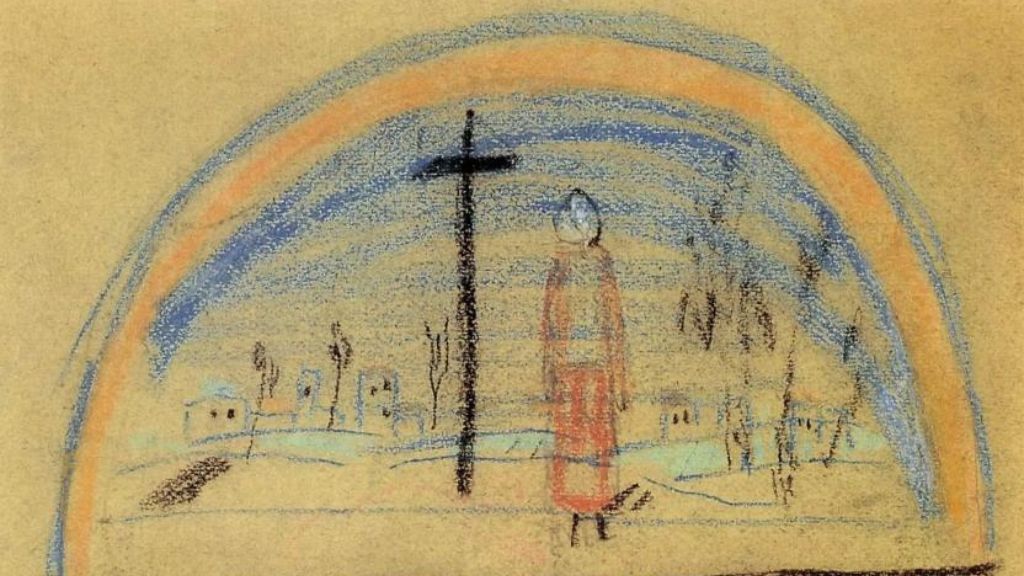

Despite the artist’s strong connection to his homeland, unfortunately, only one of his works can be seen here: in the National Art Museum of Ukraine in Kyiv is stored “Peasant Woman and Cross” (1930).

“Peasant woman and cross” (1930). Photo: National Art Museum of Ukraine

Other European Cities

Malevich’s works are displayed in museums across Europe, mainly in sections of contemporary art: in the Ludwig Museum in Cologne, the Wilhelm Hack Museum in Ludwigshafen, the Basel Art Museum in Basel, the Sefirot Foundation in Vaduz, the Peggy Guggenheim Collection in Venice, the Albertina Gallery in Vienna, the Museum of Modern Art in Stockholm.

Russia

The world’s largest collection of Malevich’s works is stored in Russian cities: in the Russian Museum in St. Petersburg are displayed, for example, “The Red Cavalry Riding,” “Three Female Figures,” and the “Black Square” is kept in the Hermitage. In Moscow, a vast collection is located in the Tretyakov Gallery, among the canvases are “Self-Portrait,” another “Black Square.”

- “Three Woman Figures” (1930). Photo: Russian Museum

- “Self-Portrait” (1933). Photo: Russian Museum

USA

Although Malevich never visited the United States, his art is held in high esteem here: in the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Leonard Hutton Galleries, the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, the Yale University Art Gallery, and the Harvard Art Museums.

Creating his own artistic world, challenging centuries-old painting tradition—was a bold mission diligently pursued by Malevich during his lifetime. There are only color and form, and thanks to them, one can create using one’s imagination, not inheriting the world we live in—this was the philosophy of the artist that made him famous all over the globe.

Cover photo: Afisha.London / Midjourney

Read more:

Antonio Canova’s ‘Three Graces’: Crafting a Neoclassical Masterpiece

Bakst, Benois and Dobuzhinsky: How an Extensive Collection of Russian Art Ended Up in Oxford

Boris Anrep in London: A Don Juan and the Love of Anna Akhmatova

SUBSCRIBE

Receive our digest once a week with quality Russian events and articles