Serge Lifar: reformer of the Paris Opera, the protégé of Sergei Diaghilev, and friend of Coco Chanel

Serge Lifar – a Ukrainian dancer, choreographer, the protégé of Sergei Diaghilev, father of the Ballets Russes, and a close friend of Coco Chanel – is known as the man who revolutionised the perception of ballet in Europe. As head of the Paris Opera, he introduced a series of sweeping reforms that elevated ballet from a mere divertissement to a grand spectacle in its own right. A divinely gifted dancer, he is remembered by audiences above all for his legendary performance as Ikarus – a role that no one has been able to replicate to this day. Afisha.London magazine recounts the story of how a seemingly unremarkable young man from Kyiv made his way to Paris and became one of the brightest stars of the European beau monde.

From Red army commander to ballet dancer

There are differing accounts of the dancer’s date of birth: the Serge Lifar Foundation says it was 2 April 1905. Serge Lifar was born into a large, wealthy family in Kyiv. His father, a prosperous civil servant, ensured that young Seriozha and his siblings received a solid education and a promising start in life. Later in life, Lifar fondly remembered family New Year festivities, his father’s impressive library, summer holidays at his grandfather’s village estate, and playful adventures at gymnasium. His parents, however, intended Serge to pursue a military career and planned for him to join a cadet corps in St Petersburg. Fate had other plans.

With the outbreak of the First World War, famine and devastation came to Kyiv, and following the 1917 Revolution, the Lifar family lost their ancestral estates and savings. Serge’s life became a daily struggle for food and survival. After finishing gymnasium, he was conscripted into the Red Army, where he was immediately appointed a company commander. And then, by some miraculous twist of fate, he found himself in the ballet studio of Bronislava Nijinska – sister of the legendary ballet master Vaslav Nijinsky – where an entirely new world of beauty and artistry was revealed to him.

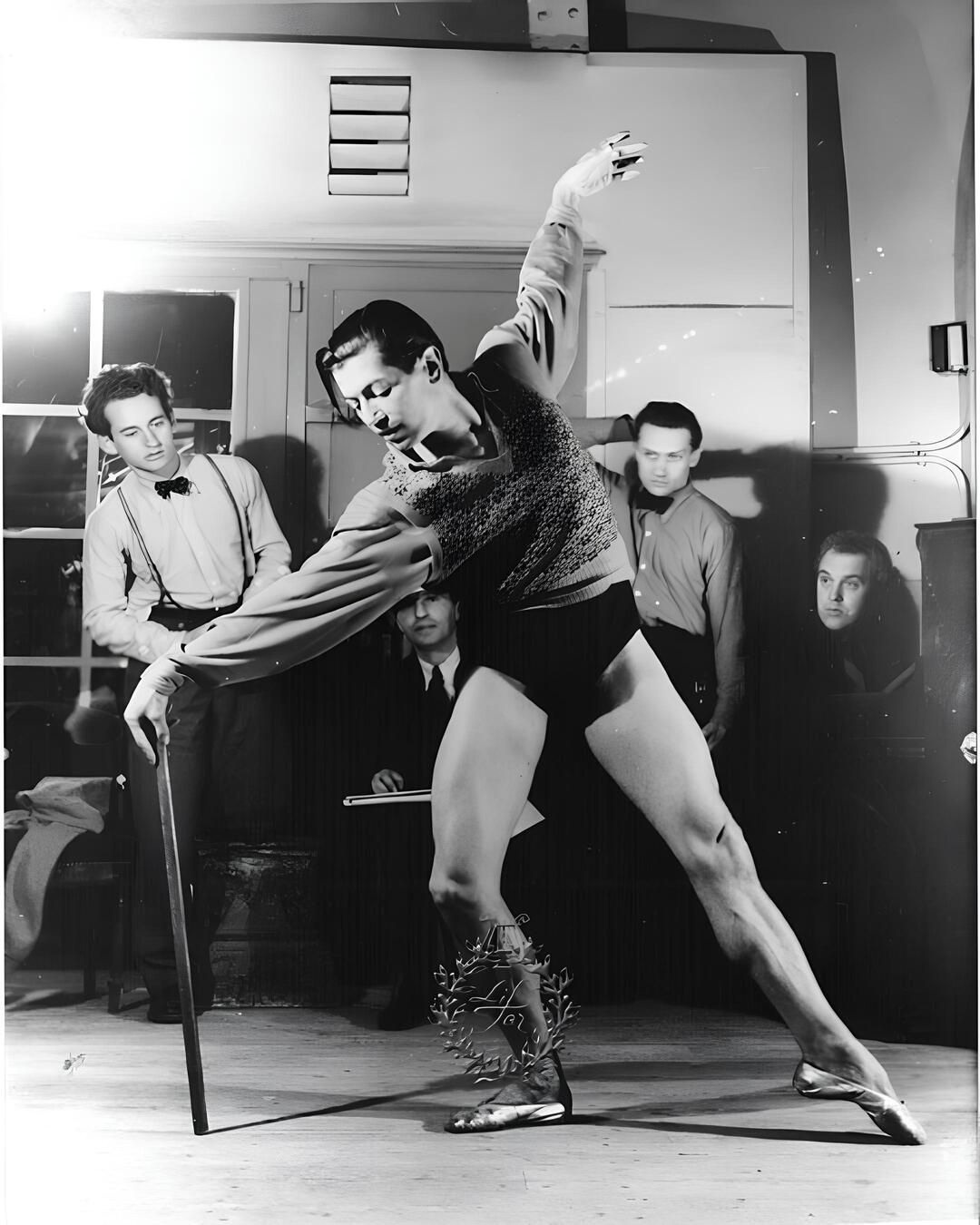

Serge Lifar as Apollon, 1928. Photo: Sasha, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Initially, Bronislava found nothing remarkable in Lifar, even describing him as hunchbacked and unfit for ballet. Who knows what his future would have been without Sergei Diaghilev, founder of the Ballets Russes? In 1921, Diaghilev invited Nijinska to rejoin his company in Europe. Having never accepted Soviet rule, she agreed. From abroad, she sent a telegram requesting five of her best students to come to Paris – Diaghilev sought fresh talent.

For Serge, this was a chance of a lifetime. Utterly captivated by dance, he couldn’t imagine life without it. He lied to his family about having a job in France and received money set aside for emergencies. One night, attempting to cross into Poland, Soviet border guards caught and returned him to Kyiv. Several months later, Lifar hired a guide who robbed him of everything but got him to Warsaw. There, he reunited with fellow students from Nijinska’s studio. The young refugees endured hunger and hid from authorities until Diaghilev finally provided money and travel documents to reach Paris.

Read more: How Diaghilev’s “Saisons Russes” influenced the European art world of the 20th century

For Serge, the difficult journey ended in triumph. In 1923, he made his debut in the ballet Flore et Zéphire on the stage of the Paris Opera. The discerning audience erupted in applause, and Diaghilev was overjoyed – he had placed his bet on Lifar, and it had paid off.

Union with Sergei Diaghilev and friendship with Coco Chanel

It was no secret that Diaghilev, the aesthete and connoisseur, preferred the company of men and surrounded himself with the most handsome of them. His troupe already had several favourites, but the moment Sergei appeared, the impresario took an immediate interest in the slender, blue-eyed young man. Lifar, for his part, made every effort to ignore his employer’s advances, which only infuriated Diaghilev. Sergei channelled all his energy into exhausting rehearsals, yet the more he evaded Diaghilev’s attention, the more the latter found fault with his performances – until, eventually, the young dancer gave in.

Serge became the impresario’s new favourite, though it should be noted that Diaghilev was generous to his protégé, cultivating in him a taste for high art. He sent him to Italy to study under the legendary Enrico Cecchetti, who had once trained Russian ballerina Anna Pavlova. Lifar was a diligent student and, under Cecchetti’s guidance, he learned to weave emotion and meaning into every movement – so much so that audiences could read entire stories in the way he danced.

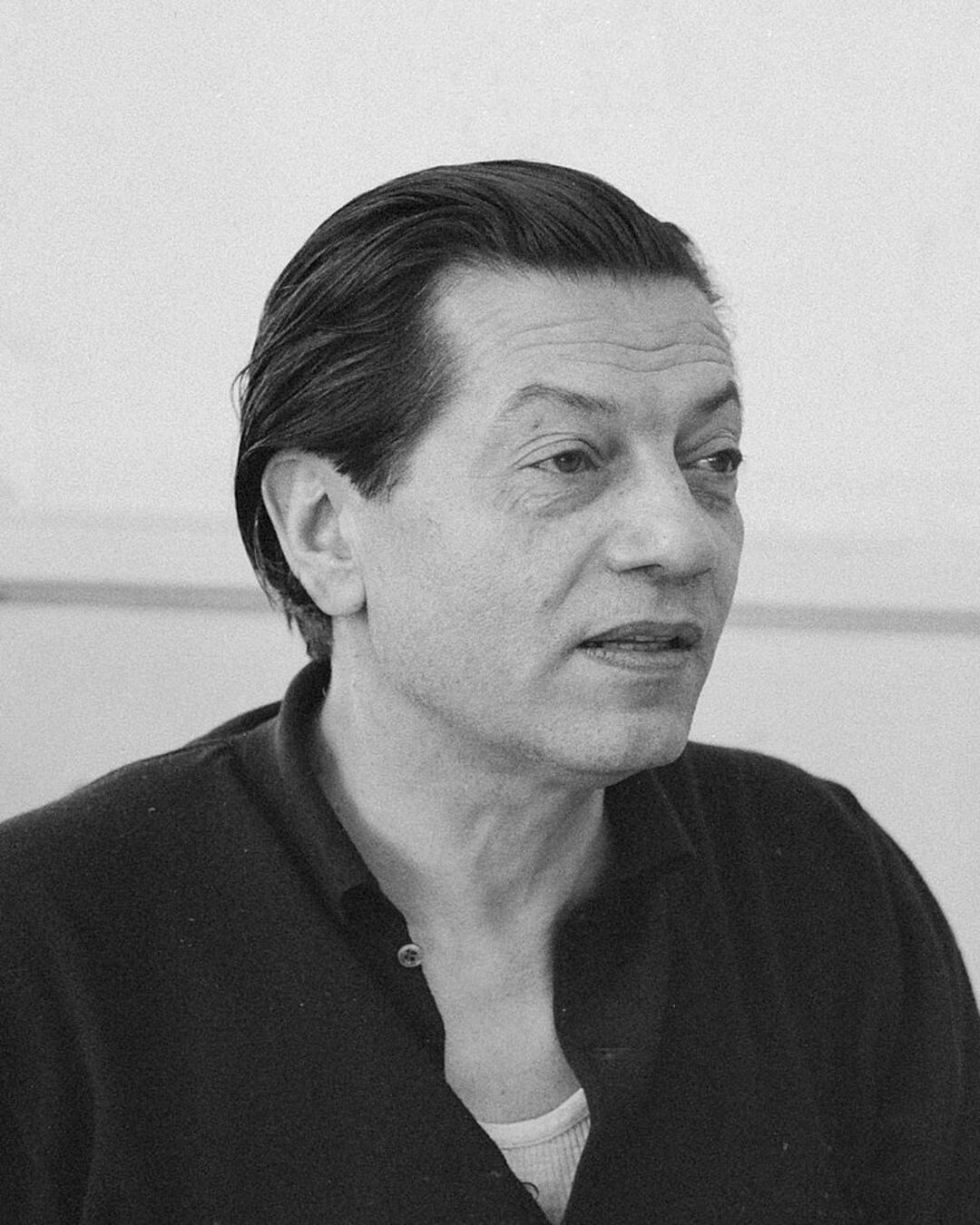

- Serge Lifar in 1932. Photo: Boris Lipnitzki from the Fondation Serge Lifar archive

- Serge Lifar. Photo: Serge Lido / Sipa Press from the Fondation archive

With Diaghilev’s support, Lifar became a celebrated soloist. After one performance of The Prodigal Son, he was called back for 75 curtain calls! In 1927, the Ballets Russes visited London with a new ballet La chatte, in which Lifar danced the principal role opposite ballerina Alicia Nikitina.

Invalid slider ID or alias.

Yet for all the success in his professional life, Serge’s personal affairs were far from simple. His relationship with Diaghilev was a tumultuous one – marked by reconciliations and break-ups – and the director of the Ballets Russes grew obsessively jealous, keeping close watch over the dancer’s every move. During this time, Lifar befriended the poet Jean Cocteau, who for many years had designed posters for the Ballets Russes. Cocteau, a notorious lover of alcohol, narcotics, and all things forbidden, began to lead the inexperienced Serge through the darker corners of Parisian nightlife. When Diaghilev discovered that the pair had slipped away to Marseille for an unscheduled holiday, he was furious, and in a fit of jealous rage even got into a fight with Lifar.

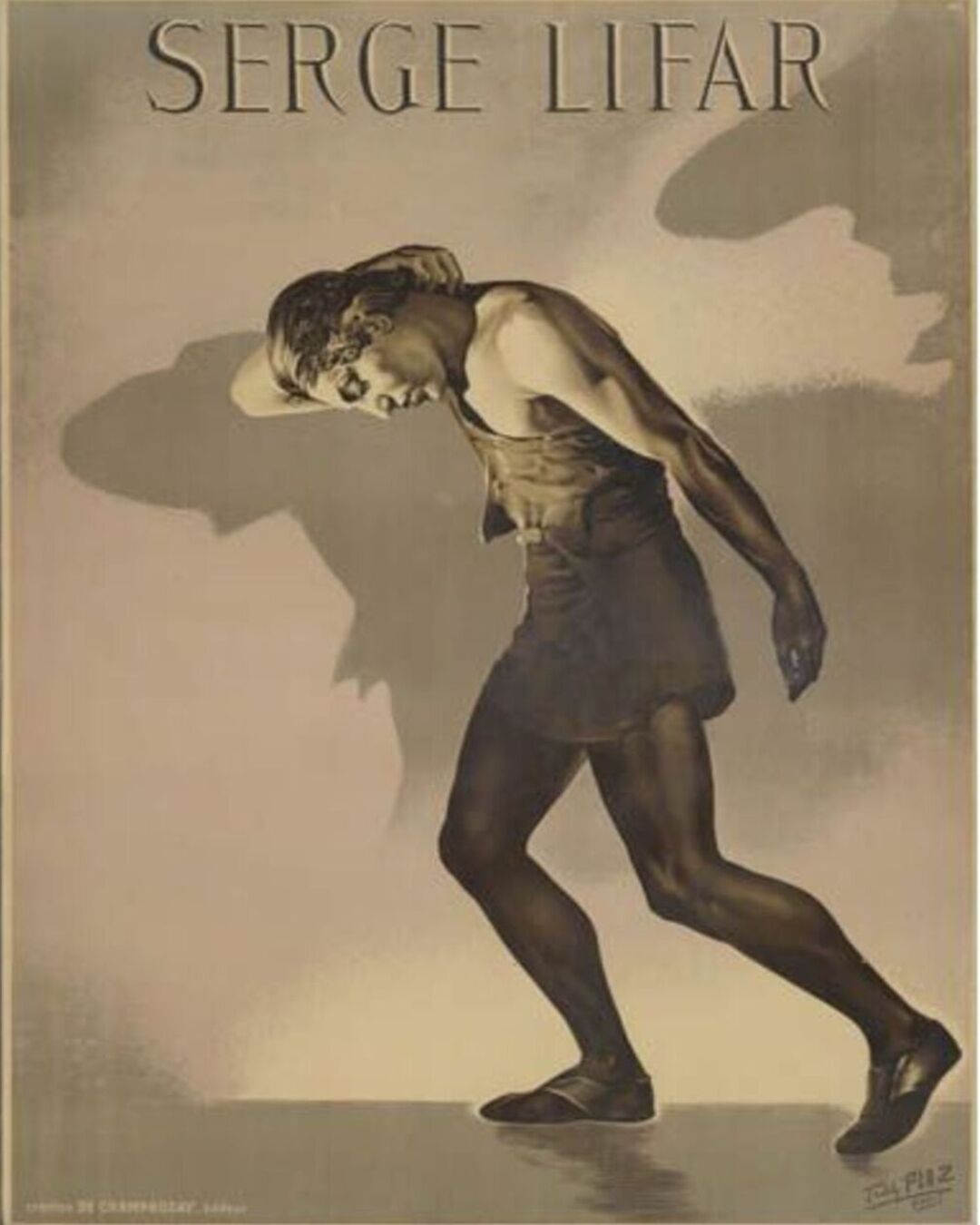

- Performance poster, 1930. Photo: Teddy Piaz, 122, Champs Elysées, Paris, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

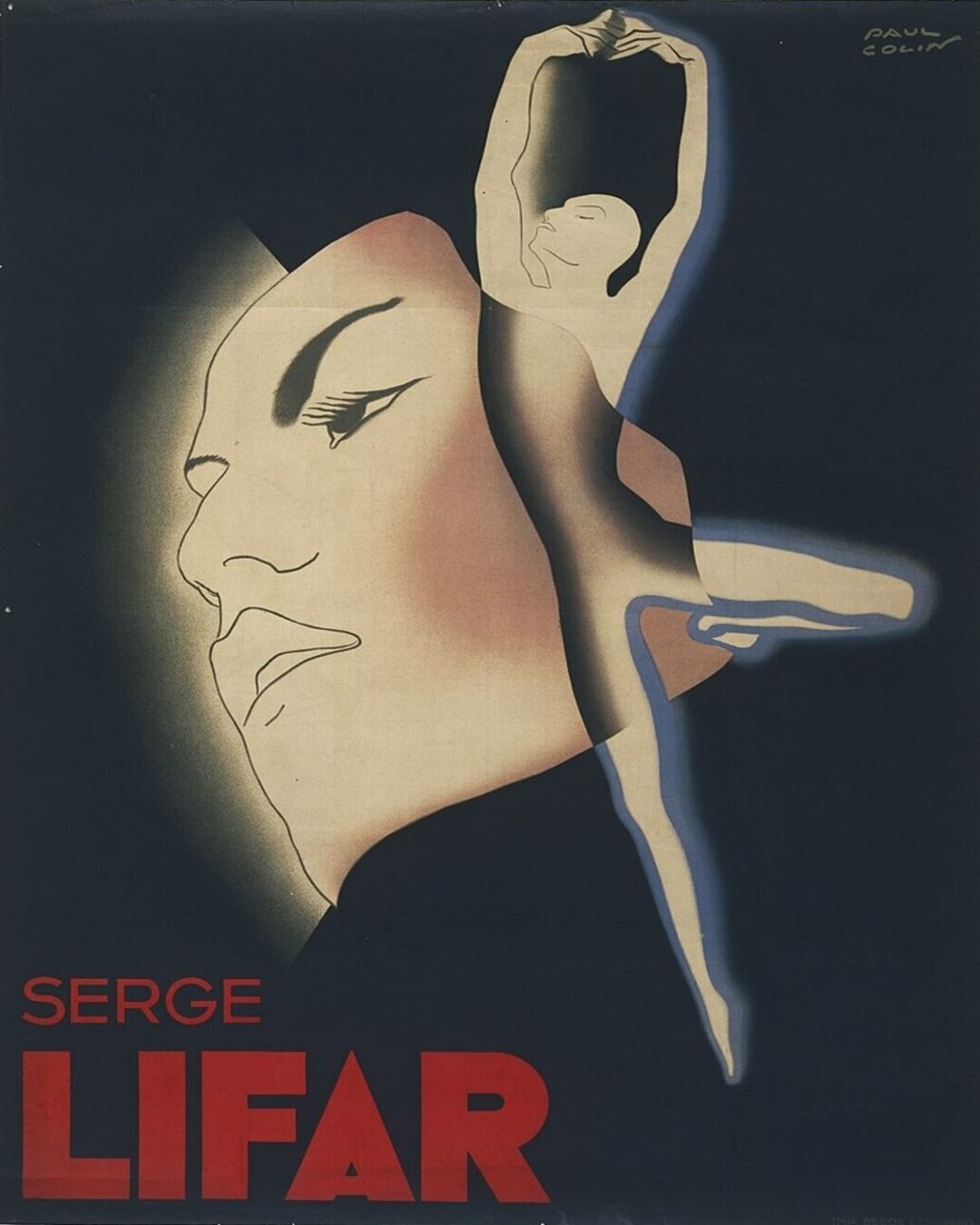

- Poster for a 1935 ballet performance. Photo: Paul Colin (1892-1985), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Still, the new friendship had its advantages: Jean introduced Serge to the legendary café La Rotonde in Montparnasse, a haunt of the Parisian avant-garde – Picasso, Man Ray, and other luminaries of the age. Lifar soon found himself welcomed into the inner circle of creative genius and quickly became a favourite muse.

By 1929, the Ballets Russes was declining. Diaghilev, weakened and impoverished, died in Venice aged 57, with Lifar andcouturière Coco Chanel by his side.

Chanel and Lifar had met in 1928 when she designed costumes for the Ballets Russes. They quickly became friends, exchanging gifts and letters. After WWII, when Chanel returned to Paris, Lifar enthusiastically promoted her fashion among his circle. In 1967, he introduced Chanel to ballerina Maya Plisetskaya.

Reforms at the Paris Opera, a romance with a Russian Princess, and a final love

Following Diaghilev’s death, the 24-year-old Lifar was accepted into the troupe of the Paris Opera, where he soon rose to the position of ballet master and director. At the Opera, Serge implemented a series of sweeping reforms that scandalised the audience but made perfect sense within the logic of an artistic environment.

In order to avoid envy and internal rivalry, he banned the tradition of presenting flowers to dancers on stage and abolished curtain calls. He introduced a strict rule forbidding latecomers from entering the auditorium once the performance had begun, and ordered that all lighting in the boxes and stalls be extinguished, leaving only the stage illuminated.

Serge Lifar with the Paris Opera troupe, 1950. Photo: G. Felici, from the archives of the Fondation Serge Lifar

But his most important innovation lay in redefining the very role of ballet. Before Lifar, ballet in Europe was typically relegated to a brief prelude or an entertaining finale to the main programme. Under his influence, ballet became an independent art form – a continuation, in many ways, of Diaghilev’s mission to introduce European audiences to the complexity and grandeur of Russian ballet as high art.

Lifar’s personal life also began to settle. After Diaghilev’s passing, he once again visited his grave on the island cemetery of San Michele in Venice. And there he met a beautiful young woman who turned out to be a Russian princess of the Romanov dynasty. Natalie Paley, cousin to Emperor Nicholas II, had fled to Europe like so many of her aristocratic compatriots after the 1917 Revolution. She began working as a fashion model and eventually found fame through her collaboration with none other than Coco Chanel.

Read more: Ballerina Anna Pavlova: a beautiful swan of two empires

Natalie’s married status did nothing to deter Serge. Their passionate romance lasted for two years – until she betrayed him with Jean Cocteau. Lifar didn’t mourn for long: he devoted all his time to work at the Paris Opera.

- Lillan Ahlefeldt-Laurvig and Serge Lifar in Venice,1961. Photo from the Fondation Serge Lifar archive

- Serge Lifar in 1961. Photo: Behrens, Herbert / Anefo, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

During WWII and Nazi occupation, Lifar controversially continued productions, even receiving Hitler at the Opera. In 1943, accused of collaboration, he faced a death sentence from the French Resistance and hid in Monaco until charges were later dismissed. Lifar was forced to go into hiding in Monaco for the remainder of the war. Only later was the charge officially declared unfounded.

In the late 1940s, the former exile returned to Paris and resumed his post. Around this time, he met the last great love of his life – and future wife – Countess Lillian Ahlefeldt-Laurvig. She had first fallen for the striking Ukrainian dancer back in 1938 after witnessing his legendary performance as Ikarus. From that moment on, Lillian became his most devoted admirer. Always impeccably dressed and adorned in jewels, she never missed a single one of his performances, and often hosted grand soirées in his honour.

In 1958, they first began to speak of marriage. For Serge, a confirmed 54-year-old bachelor, already rather worn down by life and exhausted from the responsibilities at the theatre, getting married seemed as likely as flying to the Moon. And yet, the delicate but astute Lillian not only won his heart, but also became his companion for the next three decades.

Grave of Serge Lifar at the Sainte-Geneviève-des-Bois cemetery. Photo: Afisha.London

Serge Lifar died on 15 December 1986 in Lausanne and was buried in the suburb of Sainte-Geneviève-des-Bois, near Paris. He left behind a legacy of 200 original ballets, 25 books on the history of dance, and an extraordinary collection of rare books dating from the 16th to the 19th centuries. After his death, Lillian donated part of this library to the Art Department of the Lesya Ukrainka Public Library in Kyiv.

Today, one of the rehearsal studios at the Paris Opera bears Serge Lifar’s name.

By Irina Lazio

Cover photo: Afisha.London / Midjourney

Read more:

Age of Elegance: The Edwardians at the King’s Gallery

Kurt Cobain and AI: what to expect from the new Royal Opera and Ballet season

Lydia Delectorskaya: the Russian émigrée who transformed Henri Matisse’s life

SUBSCRIBE

Receive our digest once a week with quality Russian events and articles