Great British contemporaries: Lord Norman Foster

Norman Foster is one of the most influential architects of our time and the founder of the practice Foster + Partners. His career charts a remarkable rise — from a modest upbringing in a Manchester suburb to designing some of the world’s most recognisable buildings. In 1999, Queen Elizabeth II awarded him a life peerage, naming him Baron Foster of Thames Bank, in recognition of his services to British architecture. His portfolio includes the Millau Viaduct in southern France — one of the tallest bridges ever built — the transformation of Berlin’s Reichstag, the new Wembley Stadium in London, and Apple’s futuristic headquarters in California. Afisha.London takes a closer look at the man whose sleek, high-tech structures have reshaped city skylines across the globe.

This article is also available in Russian here.

Growing up in Manchester

Norman Robert Foster was born on 1 June 1935 in Reddish, just outside Manchester. His father painted machinery at the Metropolitan-Vickers factory; his mother worked in a local bakery. He didn’t start his career at a drawing board. At 16, Foster left school and took a job as a junior assistant at Manchester Town Hall. He delivered papers, made tea, and quietly studied the building around him. Unbeknownst to him at the time, he was falling in love with architecture.

Speaking at the International Achievement Summit in London in 2017, Foster recalled the building vividly. Designed by Alfred Waterhouse in 1877, it had a profound effect on the teenager from the industrial North. “It’s a noble building. Magnificent. You walk up the stairs and everything speaks of the elevated. Light from above. Stained glass. Alcoves where you can sit. I remember even the plumbing system in the toilets. Everything was thought through. It made a deep impression on me,” he said.

Manchester Town Hall. Photo: Julius (User:Juliux), CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Wandering around Manchester became a source of inspiration. Foster admired the light filtering through the archway of the Lancaster Gallery and the rounded corners and glossy vitrolite of the Daily Express building. He didn’t yet know he would become an architect — but he was already captivated by the beauty of buildings.

Read also: A museum for every child: Frédéric Jousset and the Time Odyssey initiative

Education and early experiments

After leaving the town hall, Foster joined the Royal Air Force, where he spent two years working as a radar technician. On returning to civilian life at 20, he moved back in with his parents and took shifts at a local bakery — his free hours spent reading books by the architectural greats, often written in their own words: Le Corbusier, Frank Lloyd Wright and others.

If you’re passionate about architecture, we recommend checking out these books:

- Frank Lloyd Wright & The House Beautiful — about the harmony between architecture and interior design.

- A History of Architecture in 100 Buildings — one hundred outstanding buildings.

- Zaha Hadid — a book about one of the boldest and most innovative architects of the 21st century.

- Frank Lloyd Wright — about the life and work of one of the greatest architects of the 20th century.

In 1953, he managed to get a job at the Manchester practice John E. Beardshaw and Partners — initially as an assistant contracts manager. It was there, he later recalled, that architecture came into focus: “For the first time I came into contact with the design team. I started talking to them, getting to know them — and I was completely hooked. That was when I truly understood what being an architect meant.”

Read also: Serge Lifar: reformer of the Paris Opera, the protégé of Sergei Diaghilev, and friend of Coco Chanel

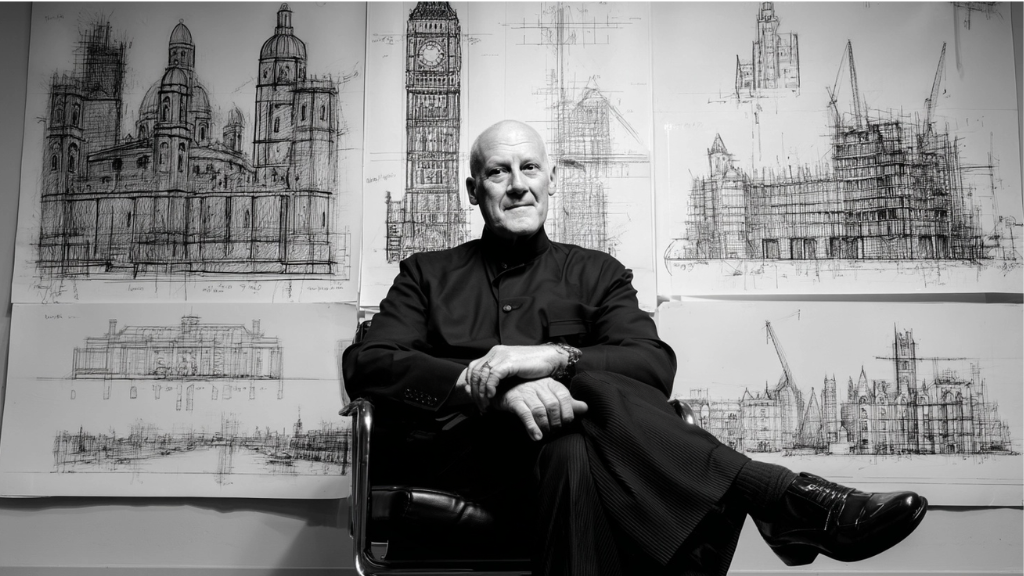

Photo: Norman Foster Foundation Archive

Realising he couldn’t progress without formal training, Foster began to prepare a portfolio from scratch. At night he redrew technical drawings, sketched the view from his window, and taught himself watercolours and gouache. Eventually, he showed his work to a senior colleague — who was impressed enough to move him into the drawing office.

In 1956, Foster was accepted into the School of Architecture and City Planning at the University of Manchester, becoming the first in his family to attend university.

To fund his studies, he worked odd jobs — bouncer at a cinema, porter in a freezer warehouse — and spent the summers driving an ice cream van for Walls through Manchester’s suburbs.

He proved a dedicated student: hardworking, award-winning, constantly sketching. On graduating in 1961, he was awarded a scholarship to study at Yale, where he met Richard Rogers — his future partner — and completed a master’s degree. It was in America, Foster later said, that he truly learned to think of architecture in context: not just buildings, but how they relate to their surroundings, infrastructure, and the public realm.

Read also: How Diaghilev’s “Saisons Russes” influenced the European art world of the 20th century

Photo: Norman Foster Foundation Archive

That philosophy would become a defining thread in his work. At HSBC’s Hong Kong headquarters (1985), the building hovers above the ground, leaving space underneath open for public use. At the Commerzbank Tower in Frankfurt (1997), winter gardens and restaurants are accessible not just to employees, but to anyone. And at the rebuilt Reichstag in Berlin (1999), a rooftop café offers panoramic views — and a symbolic chance to look down on parliament through the dome’s glass ceiling.

In 1963, Foster returned to the UK and co-founded the architecture firm Team 4 with Richard Rogers, Wendy Cheesman and Sue Brumwell. The collaboration was short-lived — creative differences led to its dissolution in 1967. Foster and Cheesman went on to establish Foster Associates, the studio that would later become Foster + Partners.

Read also: 25 years of artistic experimentation: Tate Modern marks a landmark anniversary

Norman Foster during his studies at Yale. Photo: Norman Foster Foundation Archive

Foster’s early projects were conceived not just as buildings, but as manifestos. In the 1960s, he set out to dismantle the invisible hierarchies built into architecture. The Reliance Controls factory in Swindon (1967) featured a single shared entrance and canteen for both management and factory workers — then a radical move. Foster called it a “democratic pavilion”, where offices and shop floors were separated only by glass.

Later, in 1975, his design for the Willis Faber & Dumas headquarters in Ipswich brought rooftop gardens and leisure facilities into the workplace — decades ahead of its time.

Foster + Partners: a revolution in steel and glass

These early projects laid the foundation for Foster + Partners, the architecture studio that would grow into a global practice, employing hundreds and operating across 14 countries. One of its flagship offices is in New York’s Hearst Tower — designed, of course, by Foster himself. Completed in 2006, it was the first skyscraper to rise in Manhattan after 9/11, and the first in the city to be awarded a LEED Gold certification for environmental sustainability.

The Hearst Tower remains one of Foster’s most distinctive works — a literal layering of history and modernity. Built atop a preserved six-storey Art Deco base from 1928, designed by Joseph Urban, the 46-storey glass tower rises with a bold diagonal steel frame. It’s an elegant merging of eras, and a confident statement of intent.

- Hearst Tower. Photo: Diego Delso, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Hongkong and Shanghai Bank Headquarters, Hong Kong (1985)

Completed in 1985, the HSBC headquarters in Hong Kong was the world’s most expensive building at the time, costing $668 million. With its daring suspension structure — floors hung from external supports, eliminating most internal columns — mirrored light channels and exposed glass lifts, the building was nothing short of revolutionary.

Foster created a “vertical city”, where the ground floor was opened to the public and sunlight was directed deep into the structure via a carefully designed system of mirrors. Office architecture would never be the same again.

- Hongkong and Shanghai Bank Headquarters. Photo: Foster and Partners

- Hongkong and Shanghai Bank Headquarters. Photo: Foster and Partners

Stansted Airport Terminal, London (1991)

For London’s Stansted Airport, Foster envisioned a space where travellers would feel more like they were in a park than a terminal. A canopy of steel ‘trees’ supports the roof, allowing light to flood in. The layout eliminates gloomy corridors — passengers move on a single, open level. It’s functional and serene in equal measure.

Read also: Cecil Beaton: the garden of inspiration

Stansted Airport. Photo: Foster + Partners

Symbol of a new Germany

In 1999, Foster completed his redesign of the Reichstag in Berlin. The glass dome atop the historic building became a powerful symbol of Germany’s post-reunification democracy — transparent, accessible, and forward-looking. A spiralling ramp leads visitors to the summit, where they can gaze down at the parliamentary chamber below. A literal metaphor: the people above the politicians.

That same year, Foster was awarded a life peerage and took the title Lord Foster of Thames Bank — the UK’s highest honour for services to architecture, and a nod to the profound international significance of his work.

Reichstag Dome. Photo: Foster + Partners

Millennium Bridge, London (2000)

Opened in 2000, this footbridge links St Paul’s Cathedral with Tate Modern and Shakespeare’s Globe across the Thames. It was nicknamed the “Wobbly Bridge” after pedestrians noticed a swaying motion shortly after opening. Engineers quickly intervened, and the bridge reopened in 2002 — firm, stable, and firmly established as a London landmark.

Read also: The great and terrible English pirates: the romanticised image of sea wolves

Millennium Bridge. Photo: Foster + Partners

30 St Mary Axe (‘The Gherkin’), London (2003)

Perhaps the most recognisable of all Foster’s buildings, the elliptical 40-storey tower in the City of London — known affectionately as “the Gherkin” — changed the skyline forever. Its aerodynamic form reduces wind loads, while spiral-shaped atriums enable natural ventilation. The result: energy use is around 50% lower than comparable towers. It’s not just a building — it’s a symbol of modern London.

How Norman Foster gave Trafalgar Square back to the people

In the 1990s, London’s Trafalgar Square was more traffic hub than public space — choked with vehicles and largely inaccessible to pedestrians. Commissioned by Westminster Council, Foster devised a masterplan that didn’t just improve the square — it transformed it.

Invalid slider ID or alias.

He eliminated the road between the square and the National Gallery, introducing a grand staircase and opening up a flexible space for gatherings, performances and quiet reflection. The materials used were steeped in heritage: bronze, 19th-century granite, and reclaimed York stone. The result? More people, more life, and a space that finally felt like it belonged to the city.

Read also: Joseph Brodsky in London: from Soviet outcast to professor at the West’s top universities

Trafalgar Square. Photo: Foster + Partners

Beijing Capital International Airport Terminal 3 (2008)

At the time of its opening, Terminal 3 at Beijing Capital International Airport was the largest airport terminal in the world — covering some 986,000 square metres. Designed to serve as the primary gateway to the 2008 Olympic Games, the structure was shaped to resemble a dragon — a potent symbol in Chinese culture. Its red and yellow colour scheme echoed traditional Chinese architecture. With a capacity of 90 million passengers a year, it was scale and symbolism fused into a single megastructure.

Apple Park, Cupertino, California (2017)

The circular headquarters of Apple — known as The Spaceship — was Steve Jobs’s final project and perhaps Foster’s most ambitious corporate commission. A vast 260,000-square-metre ring designed for 12,000 employees, it sits within a 30-acre park planted with 9,000 trees. Four-storey glass panels blur the boundary between inside and nature. Powered entirely by rooftop solar panels, the site runs on 100% renewable energy.

Foster and Jobs would often walk the garden paths together, fine-tuning the vision. According to Foster, Jobs wanted a building that would spark creativity. After Jobs’s death in 2011, Foster saw the project through to completion — as a tribute to their friendship.

Apple Headquarters. Photo: Foster + Partners

Bloomberg Headquarters, London (2017)

Described as the most sustainable office building in the world, Bloomberg’s London headquarters achieved an unprecedented 98.5% BREEAM score. A bespoke ventilation system mimics ocean currents; bronze “petal” ceilings diffuse natural light throughout. The building uses 73% less water and 35% less energy than comparable offices. In 2018, it was awarded the Stirling Prize.

“This is not just a building — it’s an ecosystem,” Foster remarked. From the artwork to the furnishings, every element was created specifically for the space.

Read also: Sustainable Technology: The Restart Project

Bloomberg Headquarters. Photo: Foster + Partners

The Queen Elizabeth II memorial

In 2025, Foster + Partners was chosen to design the official memorial to Queen Elizabeth II. The project will be built in St James’s Park, next to Buckingham Palace. Norman Foster’s team proposed an elegant and symbolic ensemble: a silver equestrian statue of the Queen, a new public space by Marlborough Gate, and a glass bridge inspired by the tiara Elizabeth wore on her wedding day. According to the architect, the memorial is intended as a place of quiet reflection — a spot where people can remember and reconsider her legacy.

Photo: Foster + Partners

The architect of tomorrow

On 1 June 2025, Lord Norman Foster turned 90. He still skis cross-country and cycles regularly — and, more importantly, he continues to design.

Foster + Partners is working on plans for cities of the future, pursuing ideas around sustainable urbanism and even drawing up designs for a lunar base. In a 2022 interview with the BBC, when asked if he had considered retirement, Foster replied simply: “Why should I? I enjoy what I do.”

It’s a fitting summary. For Foster, architecture is not a job. It’s a lifelong pursuit of progress, a way of imagining — and building — a better world.

Share this article with your Russian-speaking friends – you can find it in the Russian version of Afisha.London magazine’s website: read here

Cover photo: Afisha.London / Midjourney

Читайте также:

Dave Gahan and Depeche Mode: icons of British modernity

SUBSCRIBE

Receive our digest once a week with quality Russian events and articles