Flappers — emancipated women of the 20s in the West and in Russia

In the 1920s, a real gender revolution broke out in Europe, leaving far behind the prim morals of the Victorian era and the usual way of life. Women traded long locks for glamorous haircuts, and corsets and puffy dresses for short dresses with fringe and rhinestones. It has become fashionable to organize women’s clubs, listen to jazz and desperately enjoy every minute of life. Afisha.London magazine talks about flappers — representatives of the subculture of that time, fashionable and incendiary, that left an unforgettable mark on the history of women’s emancipation.

This article is also available in Russian here

With the end of the World War I, the ideals of Victorian morality were shattered and an acute desire to live entered the world stage, backed up by bright accessories and attributes of luxury and celebration. A new generation of women no longer wanted to be confined to corsets and strict rules, in addition, the public was stirred up by the London suffragette movement, who fought for women’s rights.

In the 1920s, emancipation reached the finish line: girls from high society appropriated things that were considered to be masculine. They started wearing short haircuts, going to restaurants unaccompanied, meeting in clubs of interest, drinking alcohol and smoking in public places, working and driving a car. It was considered a special chic to do this with enchanting ease and drive — after all, you only live once. The new subculture was called flappers, and Hollywood stars of the silent film era, socialite Diana Cooper, avant-garde muse Lilya Brik and aristocrats of pre-revolutionary Russia, Gali Bazhenova and Lisa Grabbe, who became models of the Chanel fashion house, became its brightest representatives. And thanks to the eccentric Coco Chanel, who was ahead of her time, comfortable and practical things have firmly entered the wardrobe of women, emphasizing the fashionable style a la garcon.

Violet Romer in a flapper dress, 1915. Photo: Bain News Service, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

How flappers appeared

The first mention of flappers appeared in the British press at the beginning of the 20th century, where the term “flapper” was used by journalists to denote an enthusiastic teenage girl who first went out into society. And in the early 1920s, newspapers were already writing about the frivolous “butterfly flappers” — young feminists who enjoy spending their lives in drinking establishments and jazz clubs, which became fashionable due to the transatlantic cultural exchange with the United States.

Read more: Emmeline Pankhurst in St. Petersburg: the suffragette movement in Britain and Russia

Flappers allowed themselves absolutely everything and did not hide fleeting romances, which is why the older generation, brought up on the ideals of strict morality, was shocked. There is another version, that galoshes for rainy weather, which young British women deliberately did not fasten, thereby challenging social norms, made their contribution. So, they walked in them, squelching and clapping as they went. The progressive image and lifestyle of flappers combined the Hollywood film The Flapper with Olive Thomas, filmed in 1920. It was Thomas who created a popular character in cinema and became the first pin-up star.

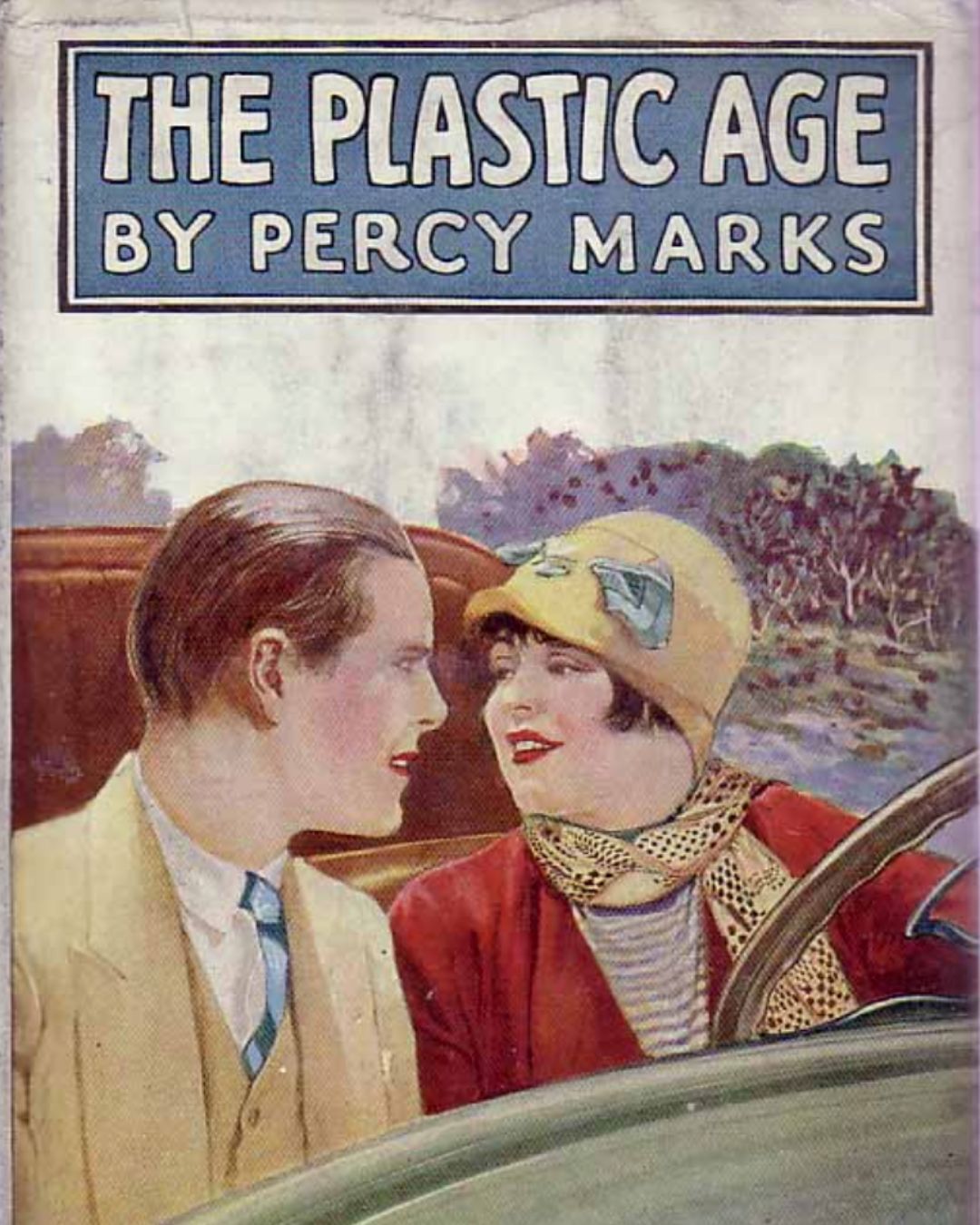

- 1924. Photo: Ellen Bernard Thompson Pyle in the 1922 Saturday Evening Post, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

- 1924. Photo: Percy Marks, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The influence of America burst into Europe in a crazy whirlwind and brought bright motives to the style of British youth. The Charleston became the most famous and uninhibited dance, and Fitzgerald’s novel The Great Gatsby became the symbol of the crazy 20s. The Charleston originated from the dances of African-American workers and was risky in performance, so in some establishments they even hung out signs “PCQ” (“Please Charleston Quietly”) to calm the ardor of the dancing crowd, under which in one of the clubs in Boston once even the floor collapsed. The Charleston was brought to Europe by the dancer and pearl of the Roaring Twenties Josephine Baker, after it conquered the Broadway stage. It is said that stiff Londoners at first considered the dance vulgar, but then Prince Edward of Wales himself danced it, and the Charleston gained popularity.

Of course, in order to dance passionately all night long, certain “equipment” was needed — a spool heel and stylish short dresses come into fashion. The outfits are decorated with glass beads, feathers, fringes and rhinestones, and short hair is styled in a beautiful wave and decorated with headbands. In make-up a bright emphasis is placed on both lips and eyes — this is how girls fought for the attention of men, who were not so many after the war. Women’s rebellion and the unrestrained atmosphere of the 20s are effectively conveyed in the film-musical Chicago, starring Renée Zellweger, Richard Gere and British actress Catherine Zeta-Jones.

How fashion and Coco Chanel influenced women’s emancipation

While the emancipated British women danced the Charleston and listened to jazz, their gentlemen sported fashionable eight-piece caps, called Gatsby. In 19th century England, such caps were worn by paperboys and athletes, but then eight-piece caps became popular among the British intelligentsia as a symbol of audacity and enthusiasm. So, self-confidence and extravagance became the hallmarks of flappers.

For example, the favorite of the London public in the 20s was American Tallulah Bankhead, one of the brightest representatives of flappers. In 1923, the actress made her stage debut at Wyndham’s Theatre, and her feathered outfit and outrageous performance in The Dancers made a lasting impression on working-class girls. Bankhead devoted 8 years to theater London, after which she returned to Hollywood, where, by the way, she auditioned for the role of Scarlett in the film adaptation of Gone with the Wind, but Vivien Leigh was approved. Meanwhile, England also had its own sparkling flappers, such as the activist and socialite Diana Cooper. During the war, she, like many British aristocrats, worked as a volunteer nurse, was also engaged in educational activities and married Duff Cooper, who later became the British ambassador to France.

- Chanel, 1931 г. Photo: Los Angeles Times, CC BY 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

- Actress Clara Bow, 1921. Photo: Nickolas Muray, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The 1920s were the heyday of the style proposed by Coco Chanel, which turned the idea of women’s fashion upside down. The rebellious and uncompromising nature of the young Gabrielle played an important role in female emancipation — even before the start of the war, she wore comfortable trousers, despised corsets and preferred clothes a la garcon (“like a boy”), which ideally suited her boyish figure. Chanel opened her first hat shop in Paris in 1910, and after its resounding success, she began dressing her clients with her characteristic purposefulness. Gabriel chooses practical fabrics, comfortable cuts and straight lines, freeing women from having to wear tight corsets and puffy skirts with dozens of meters of fabric.

Read also: How Diaghilev’s “Saisons Russes” influenced the European art world of the 20th century

The couturier also brought into fashion elements of the men’s wardrobe: trousers, waistcoats, vests, ties. However, no less interesting is the fact that the rise of the Chanel fashion house did not take place without the help of Russian aristocrats who emigrated to Paris after the 1917 revolution. In the 1920s, Chanel outfits were shown by legendary Parisian models: Princess Elizaveta Beloselskaya-Belozerskaya under the pseudonym Liza Grabbe and Elmeskhan Khagundokova, known as Gali Bazhenova. And, of course, they were both considered flappers.

Carey Mulligan in ‘The Great Gatsby’. Photo: Warner.Bros

Flappers in the USSR — but was there a boy?

Meanwhile, processes were going on in Russia — the revolution of 1917 radically changed the role of women in society. Russian women received full-fledged suffrage and were now proudly called workers, on an equal footing with men involved in building a new world. With the formation of the USSR in 1922, rich attire, furs and expensive fabrics remained in the distant past of Tsarist Russia, they were replaced by universal equality and universal clothing made from nondescript cloth. However, in the USSR, their own stars shone, who could afford to take an example from Western women vamps and flappers. Among them was Lilya Brik, the muse of Vladimir Mayakovsky, whose attractive magnetism is still a mystery to many. Brik ran her own literary salon and shocked the public by living with two men at once. Thanks to her sister and writer Elsa Triol, who lived in Paris, Lily regularly received parcels with French novelties and was rightfully considered a style icon.

Lilya Brik on a poster by Rodchenko, 1924. Photo: Legion-Media

Lilya Brik had an indefatigable imagination and loved to create unusual outfits with her own hands, she also collaborated with outstanding Russian designers, among whom was Nadezhda Lamanova. The fashion designer created outfits for Empress Alexandra Feodorovna and Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, and after the revolution she designed costumes for performances, films and stylish clothes for the masses, not inferior to Western fashion. In 1924, thanks to the assistance of Brik, the European public got acquainted with the works of Lamanova in the 20s — Paris was delighted with dresses with Vologda lace and Russian-style embroidery. Also, speaking of the growth of women’s influence on the social and cultural processes of that time, it is worth mentioning the poetess Marina Tsvetaeva. The original rebel was one of the first to write about a woman on behalf of the woman herself, previously this was done mainly by men. And her poem, written before the era of the Roaring Twenties, embodies the mood of flappers all over the world.

To be gentle, mad and noisy,

— So thirsty to live! —

Charming and smart, —

To be lovely!

Irina Latsio

Cover photo: Dorothy Sebastian, Joan Crawford and Anita Page, “Our Dancing Daughters”, 1928 (MGM)

Read more:

Lewis Carroll in 19th-Century Russia: Monasteries, Theatres and Russian Shchi

Nicholas II and George V: A History of Friendship and Duty

Dostoevsky in London and his influence on the British classics

SUBSCRIBE

Receive our digest once a week with quality Russian events and articles