Lewis Carroll in 19th-Century Russia: Monasteries, Theatres and Russian Shchi

Lewis Carroll, the author of Alice in Wonderland, is known not only for the story of the adventures of a girl in a fairy-tale land – he was also a traveller who enthusiastically discovered the magical world of other countries. His first trip outside the UK was to Russia, which the writer documented in a diary full of exciting and non-trivial notes. Afisha.London magazine plunged headlong into the study of Carroll’s Russian Diary and examined the writer’s impressions from visiting St. Petersburg, Moscow and Nizhny Novgorod.

From Charles Dodgson to Lewis Carroll

Charles Dodgson, now known under the pseudonym Lewis Carroll, was born on 27 January 1832 in the rectory in the village of Daresbury and saw the heyday of the Victorian era in Britain. He was the eldest of ten children in the family, and from childhood, he loved to show tricks, make jokes and invent things.

It is all the more surprising that with such a lively and spontaneous character, mathematics became the boy’s favourite subject, which he went to study at Oxford. After training, he remained within the university walls to lecture. He took the clergy as a deacon, which, according to the charter, was necessary for teaching at the university.

- Photo: Collect

- Six of Charles’ sisters and his younger brother Edwin. Photo: Harry Ransom Center / The University of Texas at Austin

Under the guise of a modest minister of science, Lewis wrote long mathematical treatises and ultimately gave his free time to the power of the magician who lurked inside – he wrote fairy tales, was a photographer and told incredible stories. Carroll’s photographs are recognised as some of the best of the Victorian era – he captured many famous people and created poetic images of children.

Read more: Nicholas II and George V: A History of Friendship and Duty

Carroll told fascinating stories to children, which is how university professor Charles Dodgson became writer Lewis Carroll. In the summer of 1862, there was a legendary boat trip along the river with the Liddell family, during which Carroll came up with a story about a girl named Alice who got into a magical land, and after the trip, he transferred this story to paper. In 1865, the writer published Alice in Wonderland under the pseudonym Lewis Carroll, which he coined by translating his two names, Charles and Lutwidge, into Latin.

- Alice Liddell by Lewis Carroll (1858). Photo: Lewis Carroll, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

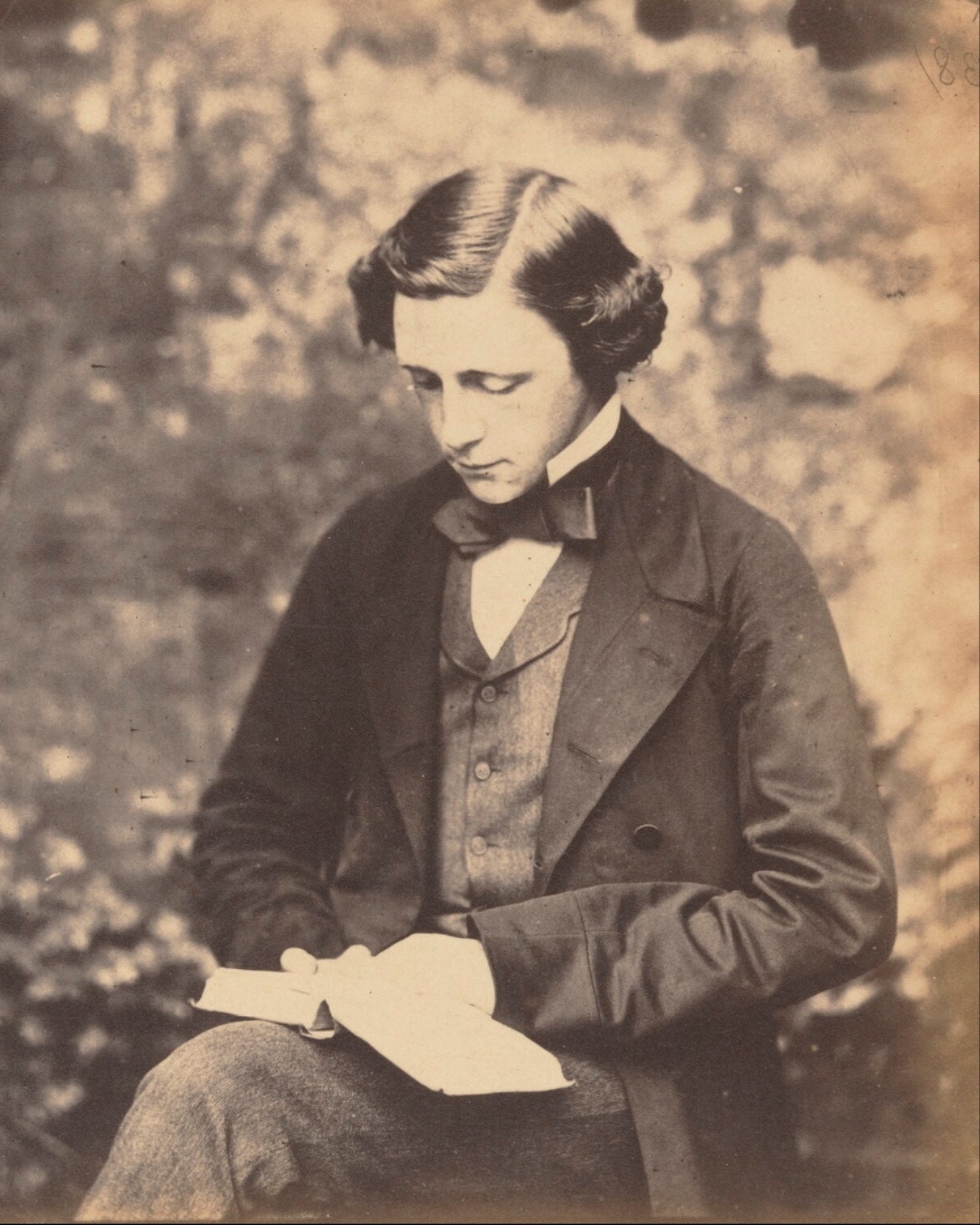

- Lewis Carroll self-portrait aged 24 at that time (c. 1856). Photo: Reginald Southey, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The book became a portal to the world of illusions and magic and turned out to be filled with symbols of the Victorian era. For example, the often late White Rabbit was an ironic representation of British punctuality, while the glass table where Alice puts the key also had its own meaning. Glass was a symbol of progress, most evident at the Great Exhibition that took place in London in 1851 and was held at the Crystal Palace – its glass walls and marvellous displays captured the imagination of the contemporary public.

European Tour and the Brilliant St. Petersburg

Carroll’s ability to notice details and reflect the mood of the era was helpful to him on his first trip outside the UK, where the writer was invited by his friend and colleague, Henry Liddon. In the summer of 1867, the two friends went to Russia, a faraway land little known to the British, not for mere interest but to establish closer ties between the Russian Orthodox and Anglican churches – at the time, this topic was widely discussed both in the West and Russia.

Read more: How Composer Dimitri Tiomkin Conquered Hollywood

The trip fell on the 50th anniversary of the pastoral service of Metropolitan Philaret of Moscow. And Liddon, who, unlike Carroll, was a preacher and had a priesthood, carried a letter of recommendation to Metropolitan Philaret from Bishop Samuel Wilberforce of Oxford. During the trip, Lewis kept diaries, where he carefully recorded every day of his travels – Oxford graduates swept through Europe and, once in Russia, visited many monasteries, theatres and fairs.

From London, Carroll and Liddon travelled to Calais and from there to Brussels, where they stayed at the famous Bellevue Hotel – at different times, the writer Honore de Balzac, the composer Franz Liszt and the Russian emperor Alexander II also stayed at this hotel. The next stops on their trip were Cologne, Berlin, Danzig and Koenigsberg (now Kaliningrad), where the two friends visited the Cathedral and from where on the morning of 27 July, they left by train for St. Petersburg. In their compartment, they met a talkative Englishman who gave them a lot of advice and warned them not to count on communicating in English in Russia.

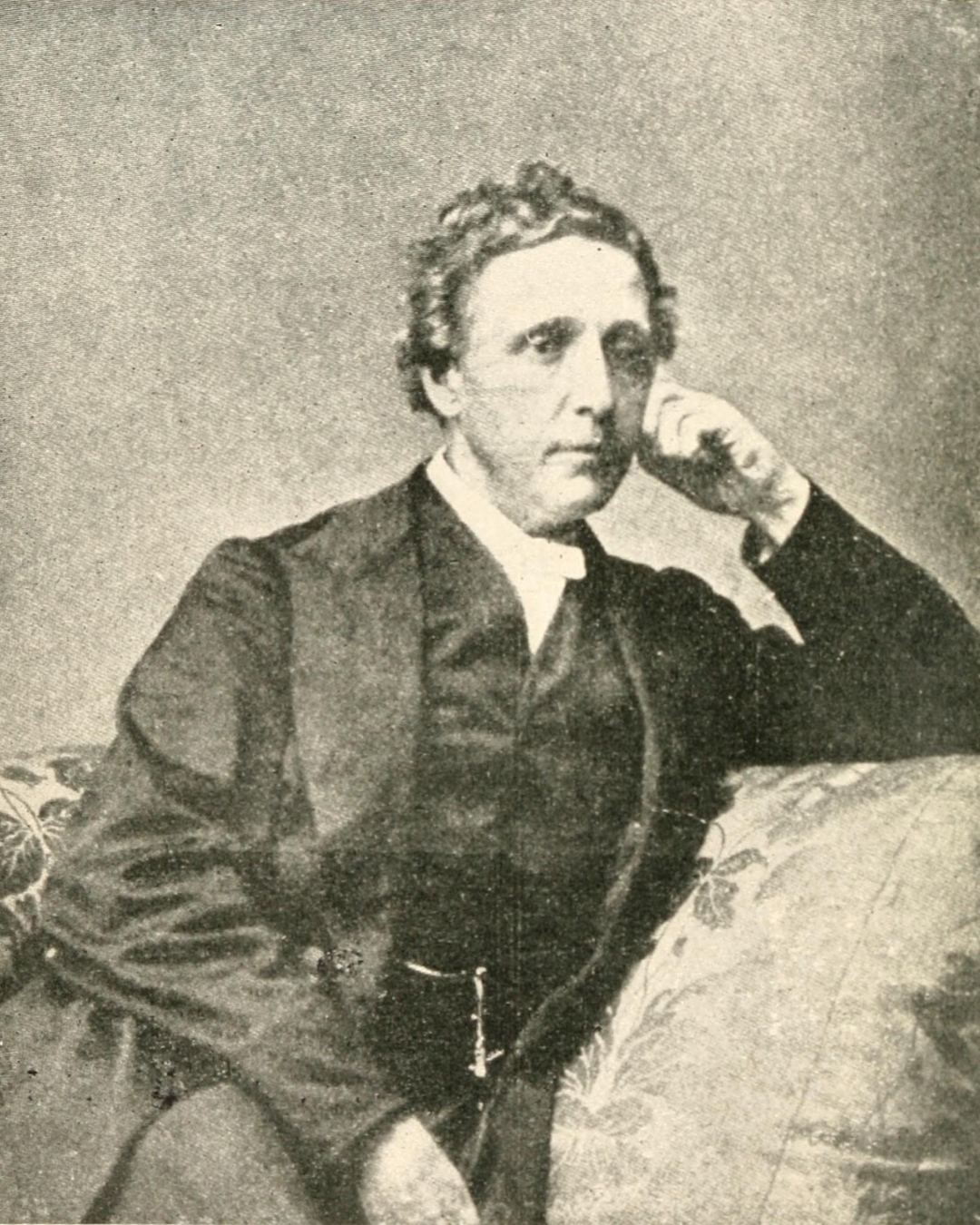

- Carroll by Oscar G. Rejlander (1863). Photo: Oscar Gustave Rejlander, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

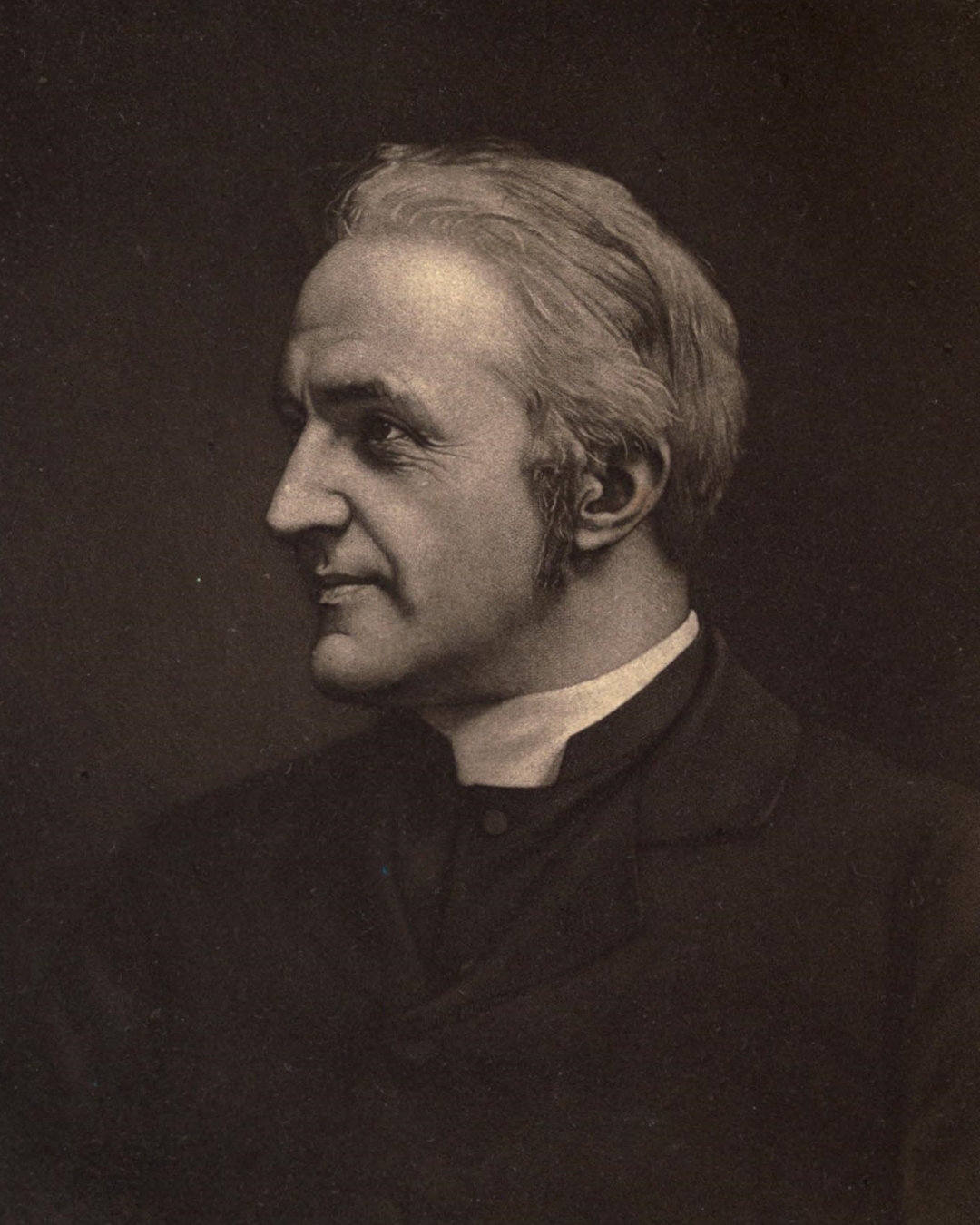

- Henry Liddon. Photo: Emery Walker, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Venice of the North greeted the travellers with gigantic golden-domed churches, the spire of the Admiralty, wide streets and avenues–much wider than in London–‘the disconcerting gibberish of the locals’ and a treat of Russian cabbage soup (shchi). Lewis noted that St. Petersburg was unlike any city he had seen before – for several days, he just walked around the ‘city of giants’, not thinking about anything. He used a mini-phrasebook to communicate with the locals: the words ‘khlaib’ (bread) and ‘vadah’ (water) were enough to buy groceries.

Read more: Charlie Chaplin: A ‘Communist’ and a Favourite of the Soviet Public

Peterhof completely amazed the writer with its splendour, about which he wrote admiringly: ‘… with a variety of beauty and a perfect combination of nature and art, I think these gardens outshine the gardens of Sanssouci’. Walking along the alleys of the palace complex, Carroll was fascinated by the bronze and marble statues skillfully built into niches with a black background to make the figures appear more embossed. And on 2 August, friends went by train to Moscow – in Sergiev Posad, they were waiting for a meeting with the archbishop.

Moscow and Aladdin at the Nizhny Novgorod Theatre

In Moscow, the Brits stayed at the Duzo Hotel, located at the intersection of Teatralny Proyezd and Neglinnaya Street – Fyodor Dostoevsky and Leo Tolstoy also liked to stay there. Moscow left Lewis with the impression of ’a wonderful city, a city of white and green roofs and canonical towers’, ‘churches resembling clusters of colourful cacti’, the interior decoration hung with icons and lamps, and pavements resembling a ploughed field. The writer especially remembered the cabbies, with whom he somehow managed to bargain and knock down the exorbitant price set. Together with Liddon, they went to the Sparrow Hills, from where a magnificent panorama of the Moscow River opened up to them, and attended a service in the Petrovsky Monastery, which impressed Carroll with music and incomprehensible to him but spectacular rites.

Read more: Boris Anrep in London: A Don Juan and the Love of Anna Akhmatova

From Moscow, colleagues made a short trip to Nizhny Novgorod – there, they got to a curious fair where Lewis enthusiastically bought icons. And in the evening, they went to the Nizhny Novgorod Theatre. However, the writer was left with a rather grim impression of the modest undecorated building. During the intermission, he worked diligently on translating the performance program to get an idea of what was happening on stage. It was challenging for Carroll to watch the play in Russian, but he still was delighted with the burlesque rendition of Aladdin and the Magic Lamp.

- Self-portrait taken by Dodgson, circa 1872. Photo: Harry Ransom Center / The University of Texas at Austin

- Self-portait taken by Dodgson, circa 1895. Photo: Harry Ransom Center / The University of Texas at Austin

On 12 August, there was a meeting at the Trinity-Sergius Lavra, which was the main reason why the British overcame such a complex and winding path to Russia. They met with the archbishop a few days before the official holiday, and the writer noted this day as one of the busiest of the trip. The foreign guests were invited to a service that impressed them with the complexity of the rites – they even had the honour of watching the clergy take communion. Then they were shown a painting workshop with icons and a sacristy with precious stones, crosses and embroidery.

Read more: Roma Liberov. Russian Emigration a Hundred Years Ago and Now: What Unites the Two Generations?

In the palace, they were introduced to the archbishop, with whom they spoke for an hour – since the clergyman spoke only in Russian, Bishop Leonid participated in the conversation as an interpreter. After the meeting, the theology student showed the guests the underground cells of the hermits, where they spent many years, which horrified the writer, who, at the thought that people live there alone with a single dim lamp, felt uneasy. With a sense of accomplishment, the British returned to Moscow – there, at dinner at the Trinity Hotel, they were presented with a bitter tincture of mountain ash and shchi with a jug of sour cream.

Hermitage in St. Petersburg and Beautiful Paris

In St. Petersburg, the friends continued their cultural program and, of course, went to the Hermitage. At the museum, Carroll was captivated by the picture of a storm with a fragment of the mast of a lost ship – Ivan Aivazovsky’s masterpiece, The Ninth Wave. The writer called it the most amazing of Russian paintings and noted that many artists tried to achieve the fantastic effect of the rays of the sun passing through the pale green crests of the waves, but no one succeeded in doing it as perfectly as Aivazovsky. Over the past few days in the city, the British met the sunset on the spit of Vasilyevsky Island, attended a service in the Alexander Nevsky Lavra and saw the Nikolaevsky Bridge over the crimson-green sea in the splendour of the setting sun.

- Lewis Carroll in later life. Photo: Stuart Dodgson Collingwood, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

- The grave of Lewis Carroll at the Mount Cemetery in Guildford. Photo: Jack1956 at English Wikipedia, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

On 26 August, a train to Warsaw was waiting for travellers. They passed a series of European cities on the way to London: Wroclaw, Dresden, Leipzig, Giessen, the spa town of Bad Ems, Paris and Calais. In the most romantic city on earth, friends walked along the Champs Elysees and went to the Bois de Boulogne. Lewis admitted that he was no longer surprised by the French, who considered London ‘dull’ – the abundance of parks, gardens and reservoirs made Paris alive and beautiful.

Read more: The Life of Sergei Rachmaninoff and His Visits to the UK

The creator of Alice in Wonderland died of pneumonia on 14 January 1898 at the age of 65 and was put to rest at the Ascension Cemetery in Guildford, Surrey. Thirty-seven years after his death, the diary with notes on Russia that Lewis kept for himself was first published by John McDermott (The Russian Journal and Other Selections from the Works of Lewis Carroll). Today, the Diary of a Journey to Russia in 1867, or a Russian Diary, which includes not only notes by Lewis Carroll but also essays by Virginia Woolf and Alan Milne–the author of Winnie the Pooh–can be purchased both in Russia and in the UK.

Irina Latsio

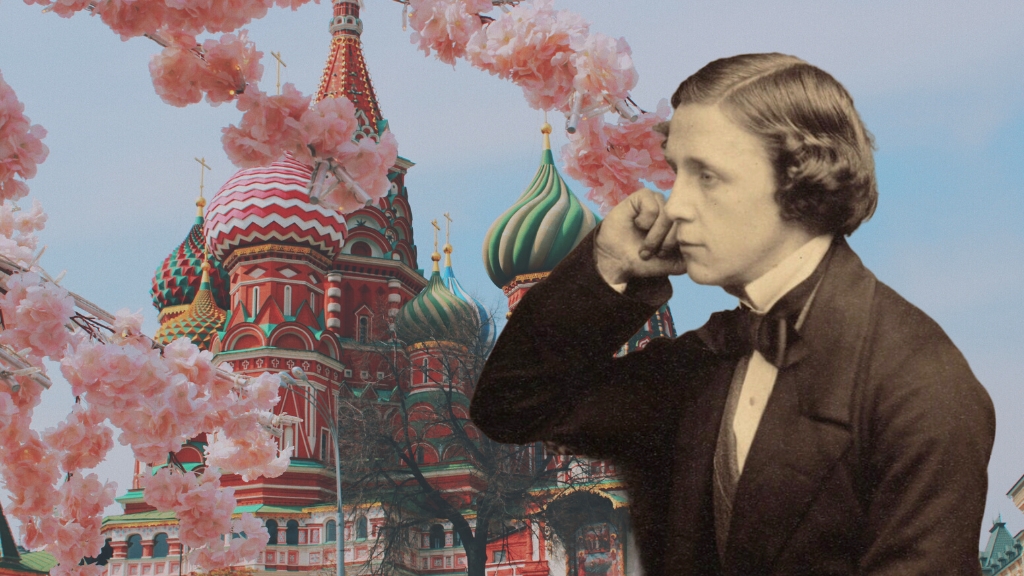

Cover photo: Lewis Carroll, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons / Vierro / Pexels

Read more:

Innovator and romantic Vladimir Nabokov in Britain

Anna Akhmatova in the UK: A Poetess, Muse and Femme Fatale

Composer Pyotr Tchaikovsky in London: impressions, recognition and success

SUBSCRIBE

Receive our digest once a week with quality Russian events and articles