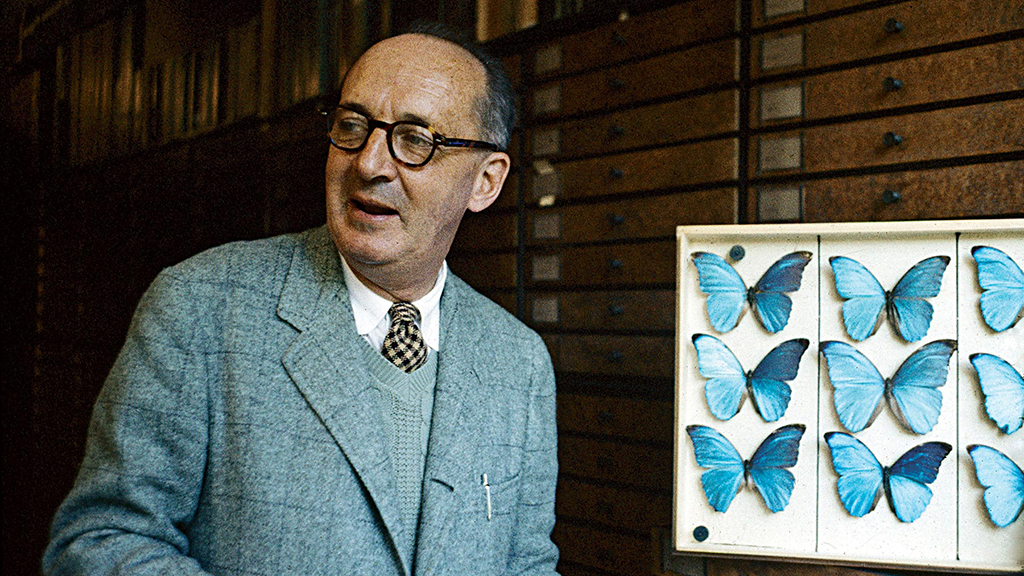

Innovator and romantic Vladimir Nabokov in Britain

The name of Vladimir Nabokov thundered after the publication of Lolita, one of the most scandalous and controversial novels in world literature. However, Nabokov is famous not only as a controversial classic — he collected butterflies, lectured on Russian literature in colleges in the United States, translated Alice in Wonderland into Russian and Eugene Onegin into English. And he was simply a genius and a living embodiment of outrageousness. In honour of the anniversary of the film adaptation of Lolita, Afisha.London magazine tells how Nabokov absorbed British traditions from childhood, studied at Cambridge and became the most provocative writer of the 20th century.

“English” childhood

The future writer was born on April 22, 1899 in the old noble Nabokov family, he was the first-born, and after him four more children were born in the family. The Nabokovs lived in a spectacular three-story mansion on one of the most fashionable streets of pre-revolutionary St. Petersburg — Bolshaya Morskaya, 47. They went on vacation to a country estate near Gatchina, and in the fall — “to the waters” abroad. Love and complete harmony reigned in the family, and passion for everything English also dominated. The writer’s mother, Elena Ivanovna, was fond of English culture and literature: instead of Russian fairy tales, she read English tales about knights to children, and only English or French women were invited as nannies and governesses. At some point, Nabokov’s father, Vladimir Dmitrievich, noticed that his sons were fluent in writing and speaking English, but they did not know the Russian alphabet. Then a village teacher was urgently hired to teach the children Russian.

The Nabokov family’s mansion in Saint Petersburg. Today it is the site of the Nabokov museum. Photo: Thomon, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

In the autobiographical novel Speak, Memory, Nabokov recalls: “In the everyday life of such families as ours, there was a penchant for everything English. An endless series of comfortable, good-quality products and all sorts of fine things for different games, and food flowed to us from the English Store on Nevsky. There were muffins, and smelling salts, and poker cards, and cocoa, and coloured-striped flannel sports jackets, and wonderful squeaky leather T-shirts, and talc-white, with virgin fluff, tennis balls in a package worthy of rare fruits. The Garden of Eden seemed to me like a British colony.”

- Vladimir Nabokov, 1907. Photo: Karl Bulla, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

- Young Nabokov. Photo: http://vnikitskom.ru/lot/?auction=89&lot=481, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The Nabokovs practically had family ties with England: Nabokov’s uncle Konstantin worked at the Russian Embassy in London, and another uncle Vasily was also a diplomat and visited the British capital. In 1916, Nabokov’s father also visited London and led a delegation of Russian journalists, among whom was the writer Korney Chukovsky — we wrote about this trip in an article dedicated to the author of Mukha-Tsokotukha. This is probably why the Nabokovs, who left Russia in 1919, did not settle in Paris, like many other emigrants, but went to London.

Vladimir Nabokov (left) and his brothers and sisters (left to right) Kirill, Olga, Sergei and Elena, 1918. Photo: Архив семьи Набоковых, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Three years in Cambridge

While still in St. Petersburg, Nabokov began his studies at the Tenishev School and became interested in literature and butterflies. Being a charming and very sensitive young man, he wrote heartfelt poems, which he published with his own money. After the October Revolution of 1917, when the Nabokovs were forced to move to Crimea, the first success came to the young writer — Yalta Voice newspaper began to publish him.

However, with the arrival of the Bolsheviks on the peninsula, the Nabokov family had to leave Crimea. On May 27, 1919, they arrived in London, settling in a house at 55 Stanhope Gardens in South Kensington, and then moved to Chelsea, at 6 Elm Park Gardens. Vladimir was then 20 years old and with the proceeds from the sale of his mother’s jewellery, he and his brother entered Cambridge. In his essay on the university, Nabokov writes poetically: “The gothic beauty of its many buildings (called colleges) stretches harmoniously upwards; the red dials on the swift towers are burning; in the openings of the age-old gates, decorated with stucco coats of arms, the rectangles of the lawn are sunny green; and opposite these very gates are full of exhibitions of shops, blasphemous, like faces sketched with a coloured pencil on the margins of an inspired book.”

Read more: Composer Pyotr Tchaikovsky in London: impressions, recognition and success

Once in England, Nabokov was impressed by how his expectations did not coincide with reality. Brought up in artificially created conditions of English culture, the young man immediately realised how different he was from the locals. His impeccable English in Russia made the students grin here, and life in the spartan conditions of the Trinity College dormitory in Cambridge contrasted with the Christmas-festive image of England to which he was accustomed to in childhood. The sophisticated Nabokov was embarrassed by local rules that considered it an honour to compete in sports, look down on professors and tutors, and despised hats, umbrellas and other means of shelter from the weather. In an essay about Cambridge, young Vladimir vividly describes his longing for lost Russia and compares English and Russian characters. “We have moments when the clouds are on our shoulders, the sea is knee-deep, — roam free, soul! For an Englishman, this is incomprehensible, new, perhaps, tempting.”

- Vladimir Nabokov (1973). Photo: Walter Mori (Mondadori Publishers), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

- Photo: Giuseppe Pino (Mondadori Publishers), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

From the third semester at the University of Cambridge, Nabokov chose “Modern and Medieval Languages” as his main course, with an emphasis on Russian and French. And at the same time, he continued to study butterflies — a flexible system of education made it possible to combine different lessons. Overly diligent students were not favoured here, so the writer had time to devote himself to poetry. It was in Cambridge where Nabokov wrote a huge number of poems imbued with a longing for the fatherland, and also seriously engaged in the study of Russian classics — for this purpose, he regularly went around market stalls in search of books by Pushkin, Gogol and Tolstoy, brought by emigrants.

The writer also continued his educational activities and founded the Slavic Society, which later became the Cambridge University Russian Society. In June 1922, Nabokov passed his final exams and joined his family in Berlin, which in the 1920s was considered the literary capital of Russian emigration. For Nabokov, Germany became fateful: there he lost his father and met his future wife.

Vera and Vladimir Nabokov, 1969. Photo: Giuseppe Pino (Mondadori Publishers), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Meeting with his wife and the meanings of “Lolita”

There are several legends about their meeting. According to the most intriguing version, Vera Slonim, the daughter of a Jewish lawyer from St. Petersburg, approached Nabokov at one of the masquerade balls for Russian emigrants in Berlin. She was wearing a wolf mask and also knew the writer’s work thoroughly, which won Vladimir over. After that, their two-year correspondence began; in the letters Nabokov, with his usual enthusiasm, admitted “Without you, I can not imagine my life…”

In 1925, the couple secretly married, since Vera’s father did not approve of her marriage to a poor writer who took the pseudonym Sirin (bird of paradise in ancient Russian art). Meanwhile, Slonim turned out to be a faithful ally of Nabokov and the main breadwinner in the family, and the writer was looking for how to apply his knowledge and talents in a foreign environment. He understood that he needed to abandon all developments and re-create his style in English, which, as Nabokov himself admitted, was a real tragedy for an accomplished writer. The flight to America from occupied Europe in 1940 opened the way for Nabokov to English-language creativity and world success — in the future he would position himself as an American novelist.

- Frame from the film “Lolita” (1997). Photo: Pathé

- Frame from the film “Lolita” (1995). Photo: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer

In America, Nabokov took up translations of the Russian classics into English, taught at Welsh College and Cornell University, and worked as a curator at the Harvard Museum of Comparative Zoology. With Vera, they were always together in everything: they collected butterflies, published new books, raised their son Dmitry… Without Vera, there would be no Lolita — the writer more than once tried to burn the manuscript, constantly rewrote chapters and tore out pages. His wife, who acted as his literary agent, predicted success for the controversial novel, and Nabokov gave in. He obeyed his practical wife in many ways.

Read more: How Diaghilev’s “Saisons Russes” influenced the European art world of the 20th century

In 1953, the writer finished Lolita but was faced with the fact that the provocative novel was banned from publishing. Eventually, in 1955, the book was published in France (however, the circulation was then arrested), and a couple of years later — in America, where the circulation of 100,000 copies was sold out in the first weeks and in terms of commercial success the novel took second place after Gone with the Wind. In England, Lolita was banned until 1959, but the speculators of London’s Soho traded illegal copies brought from France at £5 per volume. And in the USSR, the book was officially published only in the “perestroika” year of 1989, although underground it was already popular.

In 1962, the black-and-white Lolita was filmed by Hollywood director Stanley Kubrick, and exactly 25 years ago, on September 25, 1997, Lolita premiered with British actor Jeremy Irons as the treacherous Humbert. “Perverse cinema”, as it was called, made a lot of noise — in the UK and France it was banned in cinemas until the most explicit scenes were cut out, and in Australia the film was banned until 1999. Serious debates are still going on around the book and the film, although Nabokov himself insisted that this was not a love story, but a story about abused childhood and the skill with which clinically ill people can pretend to be charming and mislead others, as Humbert does with the novel’s readers. Nevertheless, the worldwide success of Lolita allowed Nabokov to move with his family to the Swiss town of Montreux and start translating Lermontov’s A Hero of Our Time and Pushkin’s Eugene Onegin for an English-speaking audience, as well as translating Lolita into Russian. With translations, the writer was assisted by his son Dmitry, a bilingual who brilliantly mastered his father’s literary techniques.

The eccentric Nabokov spent the last sixteen years of his life at the Le Montreux Palace hotel, enjoying his wife Vera’s company and the view of Lake Geneva. Nowadays, there is a monument to Nabokov in the garden of the hotel, and you can stay in the room where he lived. The great writer died on July 2, 1977, he was buried in the cemetery in Clarens, near Montreux. By the way, Nabokov left behind another legacy — the unfinished novel The Original of Laura, he started it not long before his death and, in his will, demanded to destroy it. However, in 2009, his son Dmitry decided to publish drafts, which became a gift for readers who appreciate the writer’s signature techniques. And for the British, the figure of Nabokov became closer with the publication by Bloomsbury of Robert Roper’s book Nabokov in America: On the Road to Lolita, released in 2015.

Irina Latsio

Cover photo: Marc Riboud/Magnum

Read more:

Flappers — emancipated women of the 20s in the West and in Russia

SUBSCRIBE

Receive our digest once a week with quality Russian events and articles