Charlie Chaplin: A ‘Communist’ and a Favourite of the Soviet Public

Even though today one can name at least a dozen actors whose faces would be easily recognised in almost every corner of the world, there was a time when such fame was impossible. Charlie Chaplin was the first to manage not only to achieve but to keep this kind of worldwide renown posthumously. He did it thanks to the advent of cinema; however, his natural talent and charisma played maybe even a more significant role. Chaplin was adored in the USSR, and his films were incredibly popular there, so the actor reciprocated and expressed his sympathies to the Soviet audience. Afisha.London magazine embarks on a historical journey and explores Charlie Chaplin’s connections to Russia.

The future legend of cinema was born in Victorian England on 16 April 1889 into a family of music hall actors. As a child, he appeared on stage for the first time in South London – Charlie Chaplin’s first home was on East Street in Walworth – and there began his acting career that was to last 75 more years. In 1913, Chaplin began acting in Hollywood and, in 1917, became the highest-paid actor in history after signing a $1 million contract with First National Pictures.

- Charlie Chaplin, circa 1916. Photo: History Coloured

- Photo: Encyclopedia Britannica Inc.

Chaplin was a star of the silent film era, and in the 1930s, he remained faithful to the old format, even though sound films had already appeared by then. Chaplin was an idol and even a close friend of many iconic Russian artists. For example, famous actor Yuri Nikulin once admitted that he had admired Charlie Chaplin since childhood. Also, there are many legends about the friendship between the icon of cinema and Russian ballerina Anna Pavlova.

Read more: Ballerina Anna Pavlova: A Beautiful Swan of Two Empires

Nikita Khrushchev also sympathised with the actor – their meeting took place in London when the head of the USSR arrived on his first visit to the UK. Chaplin’s love for the Soviet audience and communism landed him under the supervision of the all-seeing eye of the FBI. He was suspected of spreading anti-American propaganda and banned from entering the United States. However, despite all the mutual sympathies, Charlie Chaplin never visited the USSR.

Friendship with Anna Pavlova

They say that in Chaplin’s life, there were more women than roles. The actor was always associated with beautiful ladies: all four of his wives had a distinctively bright and expressive appearance. At the same time, the actor’s first three marriages ended with scandals. Chaplin’s biographer, Joyce Milton, even believes that his relationship with one of his wives – a very young Lita Gray – inspired Nabokov’s Lolita.

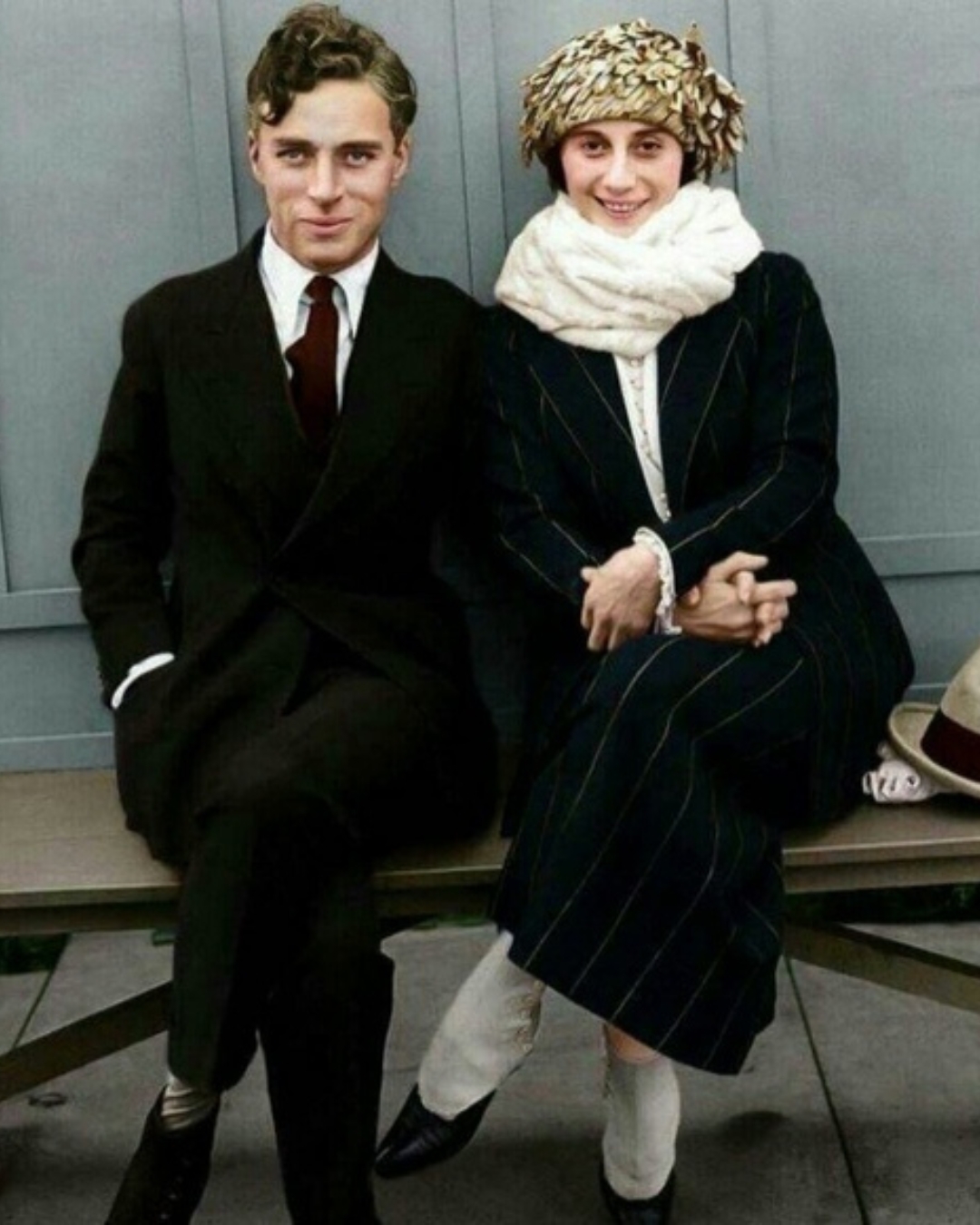

Charlie Chaplin with his fourth wife Oona O’Neill. The couple got married when the actor was 54 and she was 18. Photo: Bettmann

Chaplin met his true love only at the age of 54. Oona, who was 36 years younger than the actor, gave him eight children and became a consolation to him in his old age. However, Charlie Chaplin found a truly “rare diamond” even earlier – the legendary Russian ballerina Anna Pavlova. The artists met in London at one of the evenings arranged in honour of the “Russian swan”: in our article dedicated to Pavlova, we talked about her life in the British capital, where she moved in 1914, her career and love for swans.

Read more: Innovator and Romantic Vladimir Nabokov in Britain

Right after meeting Pavlova for the first time, Chaplin was blinded by her beauty and charisma and only found himself saying that the English language cannot convey the fullness of his feelings, so he will speak with Anna in Chinese instead. While ostensibly talking nonsense in “Chinese”, Charlie kissed the ballerina’s hand, and she laughed at his unexpected gesture. But Pavlova was already passionately in love with Baron Dandré and could only offer Chaplin friendship. And so it began.

- Charlie Chaplin and Anna Pavlova. Photo: See page for author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

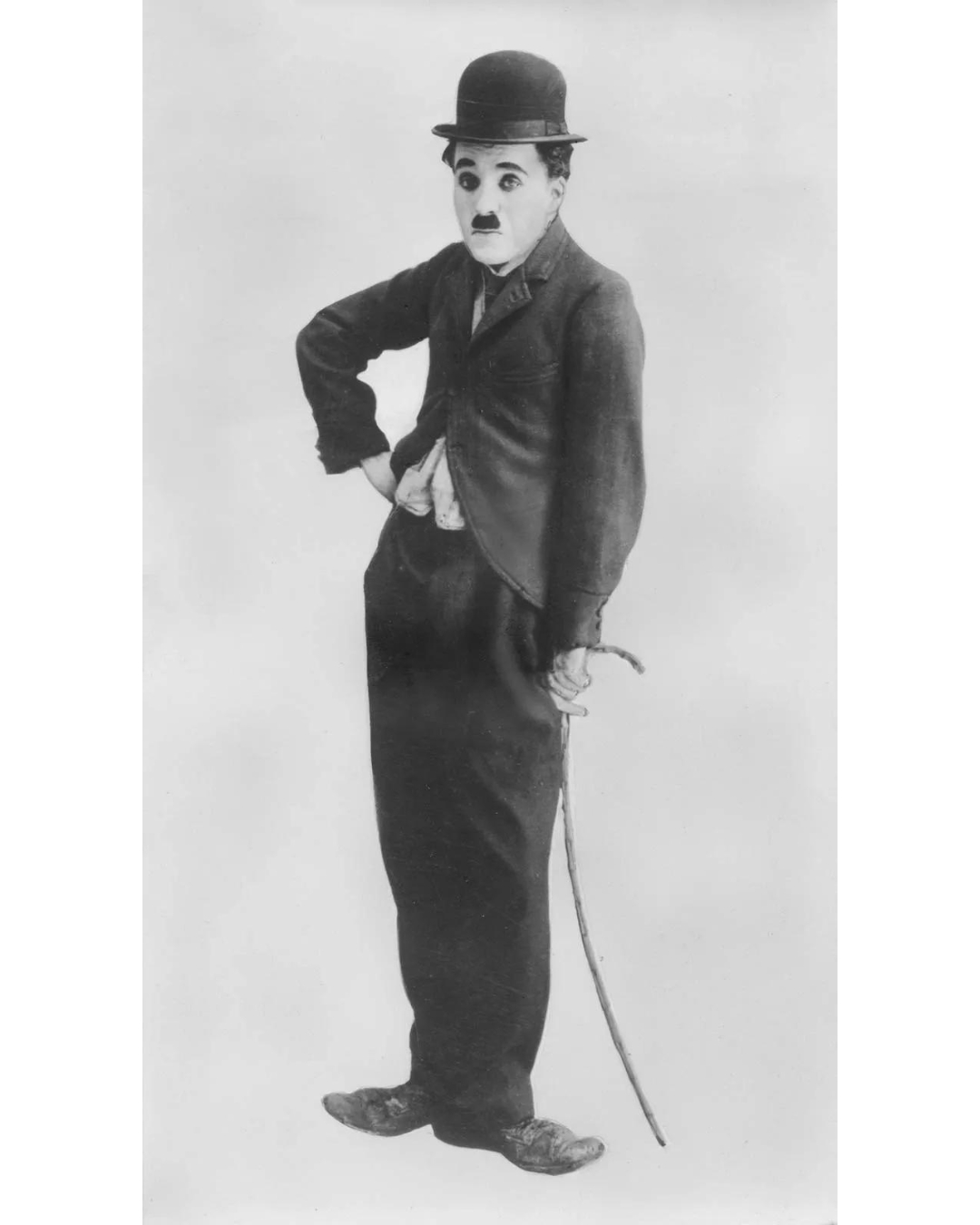

- Charlie Chaplin as the Little Tramp. Photo: Brown Brothers

They were quite alike: Charlie called himself a tramp, a role he enthusiastically played in his films, and Anna was a sylph, a spirit of the air. He helped record her exquisite dancing on film while she inspired him with her grace and lightness. In memory of their friendship, in 2021 in Saint Petersburg, the wall of a house on Italianskaya Street, where the ballerina used to live, was decorated with a fresco depicting the two artists.

From Russia with love

In the 1920s, Chaplin’s short films were a constant fixture on the screens of Soviet cinemas. The New Economic Policy (NEP), adopted by Vladimir Lenin in 1921, supported private enterprise and allowed the Soviet audience to enjoy the best of Western art and culture available in the country. However, the situation changed with the abolition of NEP in the 30s: foreign films, including those with Chaplin, became a rarity.

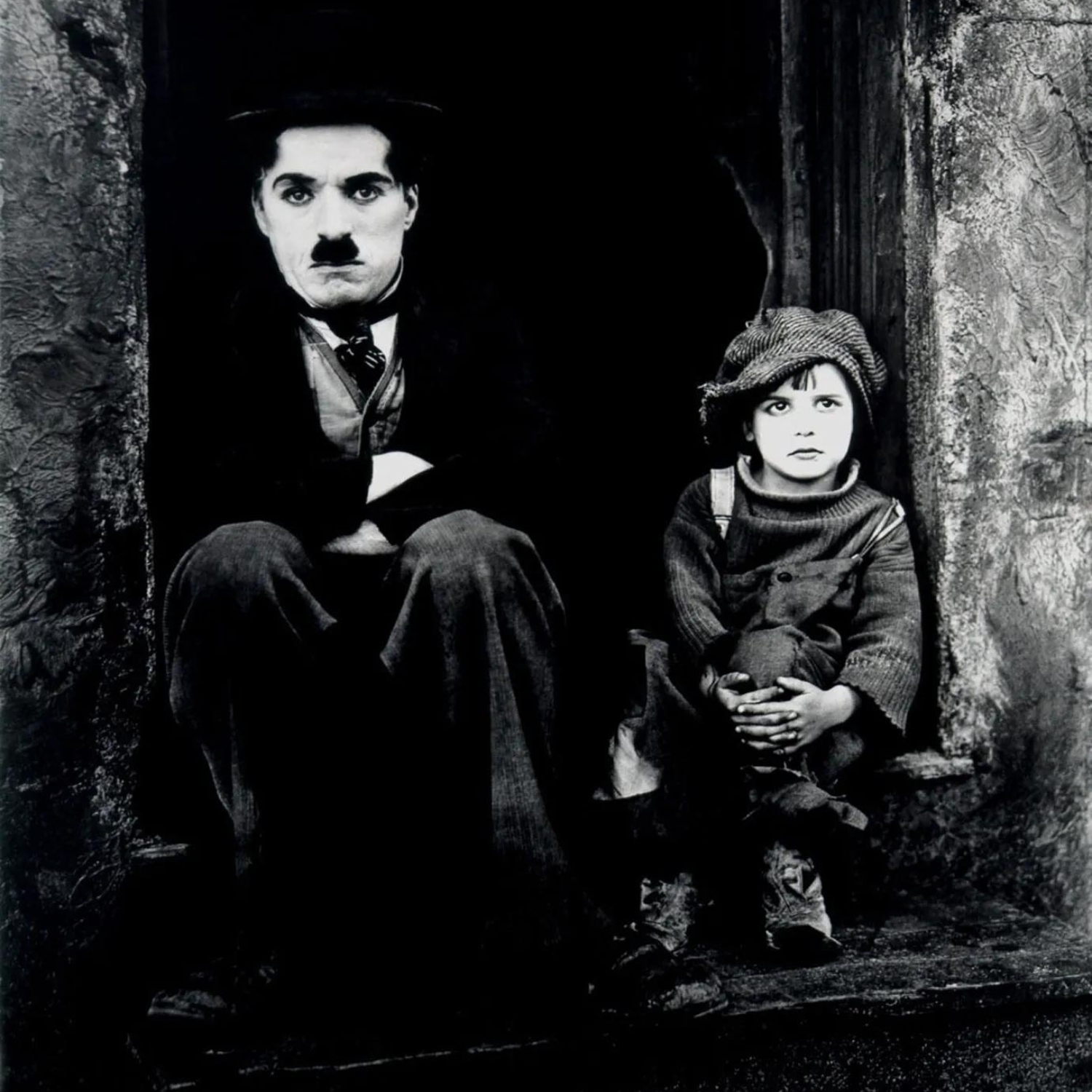

- Charlie Chaplin and Jackie Coogan in The Kid (1921) directed by Chaplin. Photo: Warner Brothers

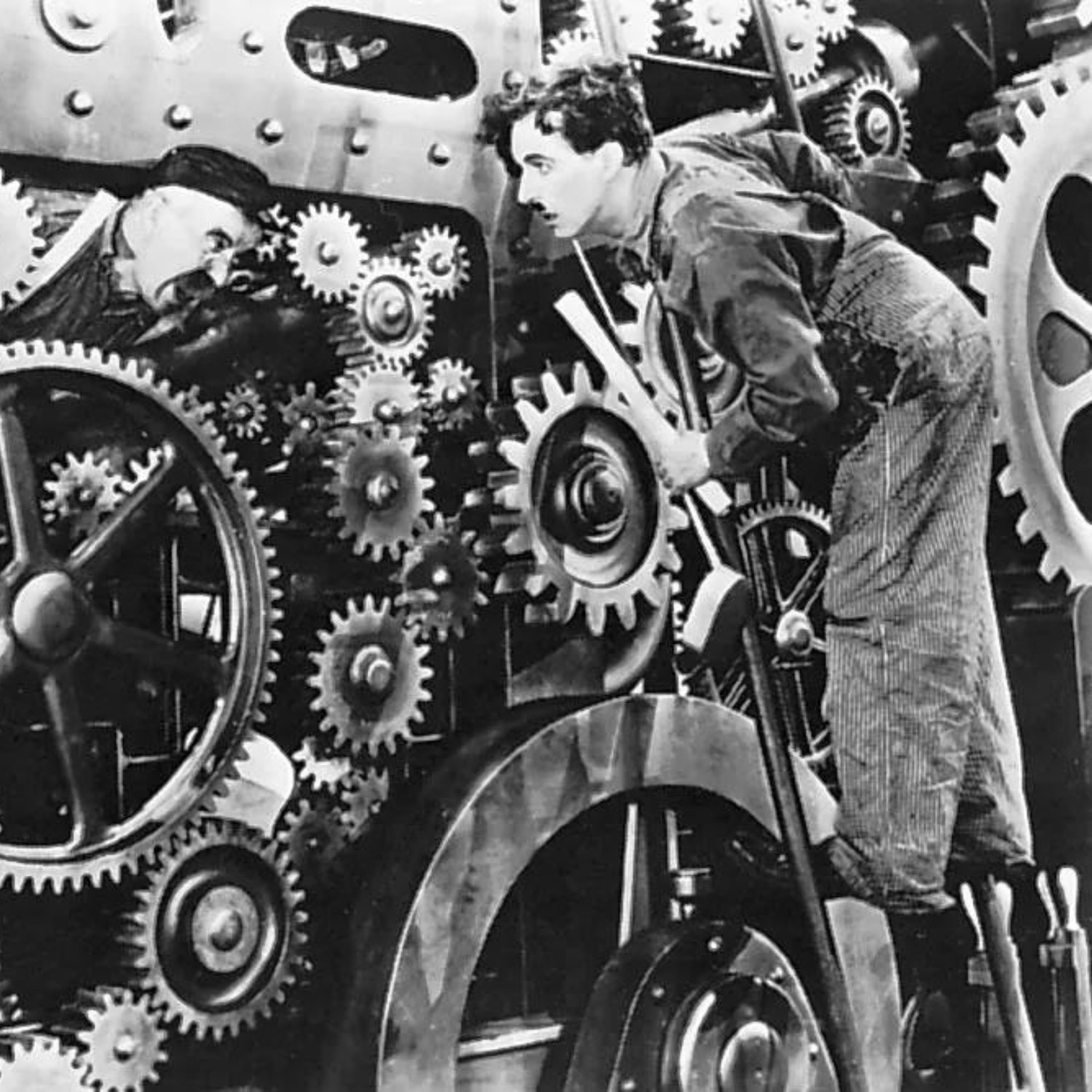

- Charlie Chaplin in Modern Times (1936). Photo: Museum of Modern Art, New York / Film Stills Archive

The well-known actor Yuri Nikulin recalled that he first saw films with the famous comedian in 1936 – City Lights and Modern Times. After watching the latter, Chaplin became Nikulin’s favourite comedian. He enthusiastically recalled: “In autumn, in rainy weather, we went with the entire family to the Green Theatre at the Gorky Park of Culture and Recreation to watch this film. The Green Theatre has a huge screen, so about thirty thousand people can watch the film. As soon as a man with a cane appeared on the white canvas, I forgot about everything else. There was no hall, and the rain disappeared somewhere. I only saw Chaplin”.

Read more: Boris Anrep in London: A Don Juan and the Love of Anna Akhmatova

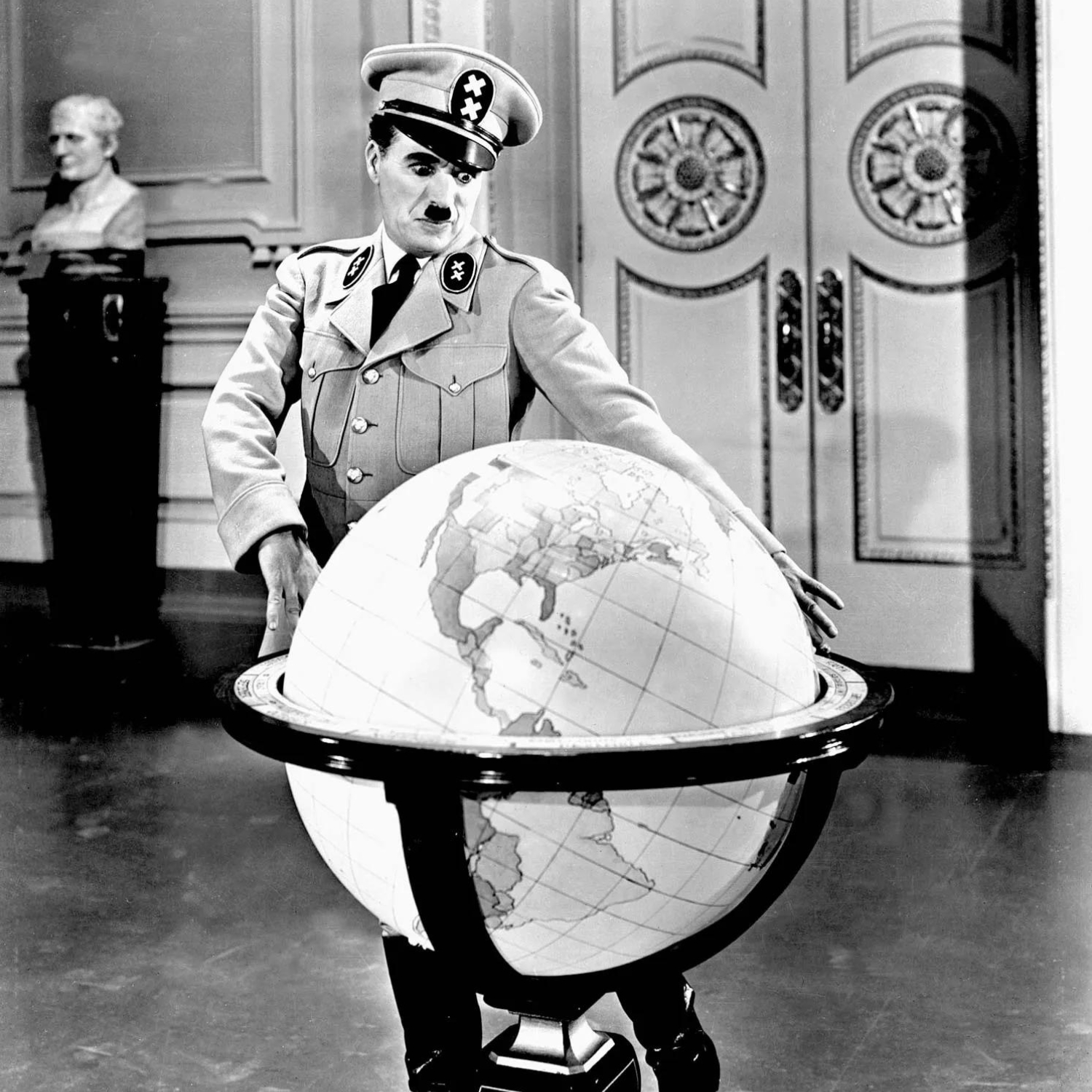

In the 1940s, Hollywood films returned to the Soviet screens. Still, Chaplin’s new release, The Great Dictator, was rejected by Stalin and proclaimed to “have no high artistic value”. Interestingly, Chaplin himself was highly sympathetic towards the communists and the policies of the Soviet government during World War II, though only in words and in films he directed.

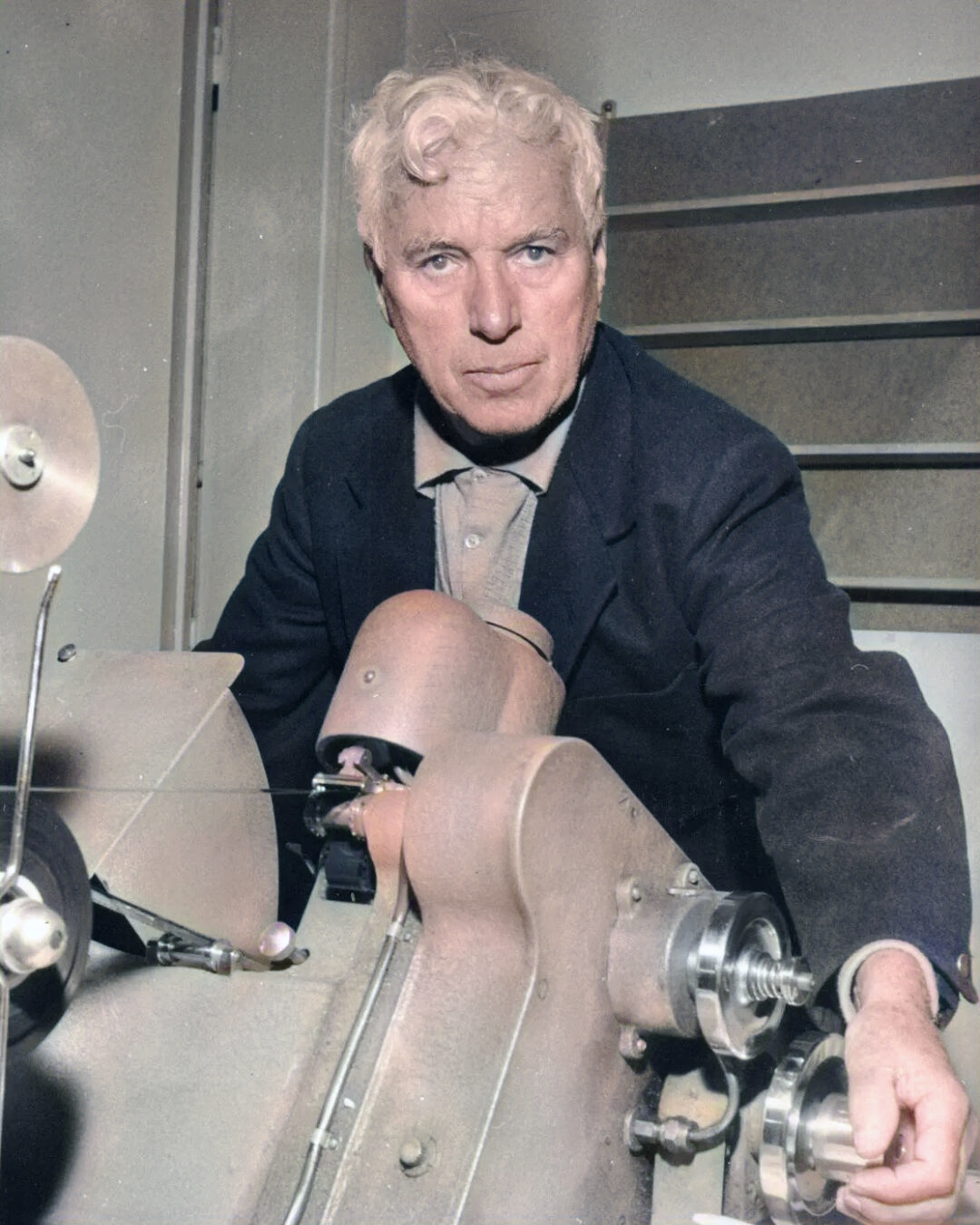

Charlie Chaplin at Foyle’s Literary Society luncheon held in his honour (1969). Photo: Jane Brown

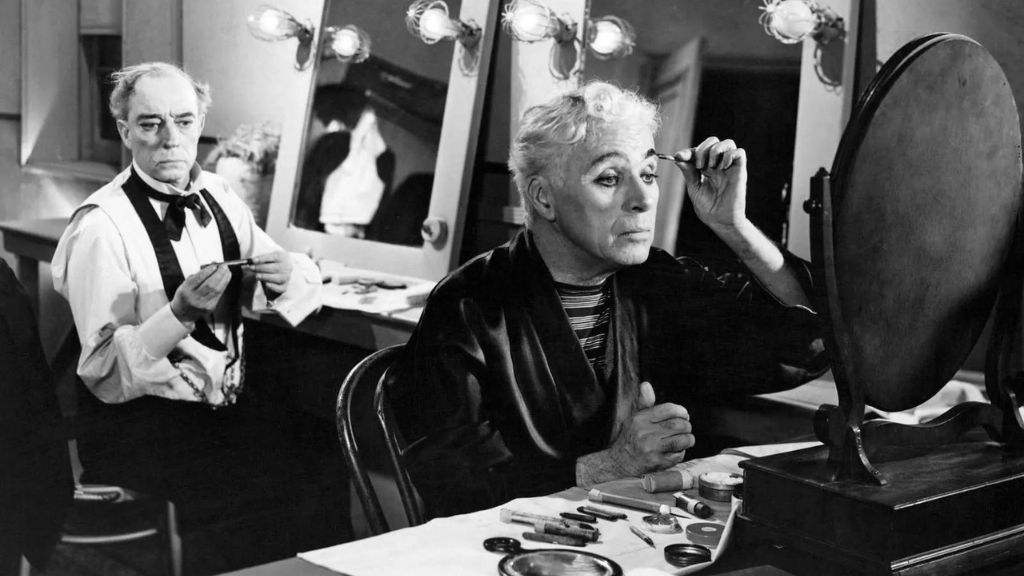

In 1952, Chaplin went to London for the world premiere of his film Limelight, but because of his bold views and political satires, the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services suspected him of being a communist spy and temporarily banned the actor from entering the country. After that, Chaplin and his family settled in Switzerland, where he lived until the end of his life.

Meeting with Soviet cultural figures

An interesting intersection between Chaplin and Russia occurred on 7 December 1953. This landmark meeting was carefully documented by the Soviet film director Grigori Aleksandrov and was kept in the archives of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union for many years. In the 1930s, the actor met Aleksandrov when he and his colleagues came to Hollywood to learn about sound films. Since then, Chaplin and Aleksandrov remained friends but were able to meet again only 20 years later, when the director, along with other Soviet cultural figures, ended up in London during the Anglo-Soviet Friendship Month.

Charlie Chaplin in Monsieur Verdoux (1947). Photo: United Artists Corporation / Private Collection

Back then, Chaplin already lived in Switzerland and came to London to meet with an old friend. They were joined by British screenwriter Ivor Montagu and Soviet director Sergei Gerasimov. The colleagues met at the luxurious Savoy Hotel near Covent Garden. They talked, of course, about the pressing issue of censorship. Chaplin was outraged by how scenes from his films were cut out in the USSR because of being considered “ambiguous”. He also resented dubbing and even subtitles. To him, a pedant to the core, any alterations to his creations seemed blatantly rude.

Buster Keaton and Charlie Chaplin in Limelight (1952), written, directed and produced by Chaplin. Photo: Celebrated Films Corporation

Charlie also told them about his plans. After his break with the United States, he experienced an unprecedented creative rise, wrote new scripts with inspiration and dreamed of creating a film that would expose the system of humiliation of human dignity, which, in his opinion, reigned in America. Although Chaplin’s fame as a cult director was already waning, Aleksandrov noted that he was still charming, full of creative energy and faith in the future.

Meeting with Nikita Khrushchev

In the 1950s, Chaplin met with the First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, Nikita Khrushchev, who was beginning to fulfil the duties of the head of the Soviet Union. The meeting, which the actor described in his autobiography, occurred at the five-star Claridge’s Hotel on the corner of Brook Street and Davis Street in Mayfair. In 1956, Khrushchev made his first state visit to Great Britain, where he was received by Elizabeth II. At one of the dinners, he was given a seat next to Churchill, who had recently left the post of Prime Minister.

Read more: Yuri Gagarin in London: How to Impress the Queen and Become a British Hero

In honour of the visit of the head of the USSR to the UK, the Soviet embassy arranged a reception at Claridge’s. Chaplin, who at the moment was in London with his wife Oona, was also invited. The artist recalled how he could barely get to Khrushchev through the hotel lobby, filled with people and bustle. They were introduced to each other right there, in the crowd. With the help of an interpreter, Khrushchev told Chaplin that his films were very much loved in the USSR and took a picture with the actor.

- Charlie Chaplin in City Lights (1931). Photo: Charles Chaplin Productions

- Charlie Chaplin in The Great Dictator (1940), written and directed by Chaplin. Photo: United Artists Corporation

The meeting could not do without a traditional glass of vodka, although the strong Russian drink was not to the actor’s taste. At the reception, Khrushchev made a speech and highlighted that he arrived in London with good intentions, and it touched Chaplin. In the morning, the newspapers were full of news about their meeting. Later, the actor would feel very sorry that this visit did not improve the relations between the UK and the USSR.

Chaplin’s grandson in Russia

Charlie Chaplin’s grandson, the Swiss acrobat, dancer and actor James Thiérrée, became a favourite of the Russian public and regularly visited the country. He inherited his famous relative’s looks, talent and masterful control of the body. However, James himself does not like being compared to his legendary grandfather. In 1998, he founded his own theatre company, La Compagnie Du Hanneton, and was awarded four Moliére Awards – this award is given for achievements in French theatre – for his shows combining pantomime and acrobatics.

In 2007, he directed a visual fantasy Au Revoir Parapluie, and its magic and versatility conquered London and Moscow. Thiérrée became a regular participant in the Chekhov International Theatre Festival and delighted fans with new masterpieces every year. In 2022, the acrobat went on a European tour and then to the festival in Sydney with a new production of Room, in which he performed as a singer for the first time. Critics have already called the performance a completely outrageous “Thiérrée-esque” nonsense withs that feels like “a damn delicious, brain-teasing evening in the theatre” afterwards.

Irina Latsio

Cover Photo: Charlie Chaplin in 1920s (Giving Colour to History)

Read more:

Emigration of the Romanovs to Great Britain: the story of Grand Duchess Xenia

SUBSCRIBE

Receive our digest once a week with quality Russian events and articles