The Life of Sergei Rachmaninoff and His Visits to the UK

Sergei Rachmaninoff is widely considered one of history’s greatest composers and pianists. However, such worldwide recognition came to him only after he had to flee his homeland and build a new life in a strange country. The composer was a virtuoso pianist and brilliant conductor, so he gave many concerts all over Europe and America, amassing impressive wealth. Nevertheless, Rachmaninoff still experienced creative block – after leaving Russia forever, he lost his inspiration and practically stopped writing music. In honour of the upcoming 150th anniversary of Sergei Rachmaninoff’s birth, Afisha.London magazine explores the composer’s thorny path to greatness and recalls his visits to the United Kingdom.

Young Rachmaninoff in Saint Petersburg and Moscow

The future composer was born on 1 April 1873 into a noble Russian family. Sergei inherited his affinity for music from his father, pianist Vasiliy Arkadyevich, who managed to squander his wife’s hefty dowry that consisted of five estates. In 1882, the last family estate in Oneg, where the young virtuoso spent the first nine years of his life, was auctioned off, and the boy’s father went bankrupt. Ironically, if the Rachmaninoff family had not suffered a financial collapse, Sergei would not have entered the conservatory and become a musician – before the unfortunate events, Vasiliy Arkadyevich was set on giving his sons a prestigious military education.

The whole family, including Sergei and his four siblings, had to move into a rented flat in Saint Petersburg. These changes were hard on the composer’s mother, Lyubov Petrovna, who was not used to the absence of servants and nannies. The stress induced by the sudden change of lifestyle combined with frequent quarrels altered the children’s perception of their mother, making her a strict and gloomy presence. However, it was she who insisted that the talented Sergei had to enter the Saint Petersburg Conservatory.

- Sergei Rachmaninoff in 1886. Photo: Russian National Museum of Music

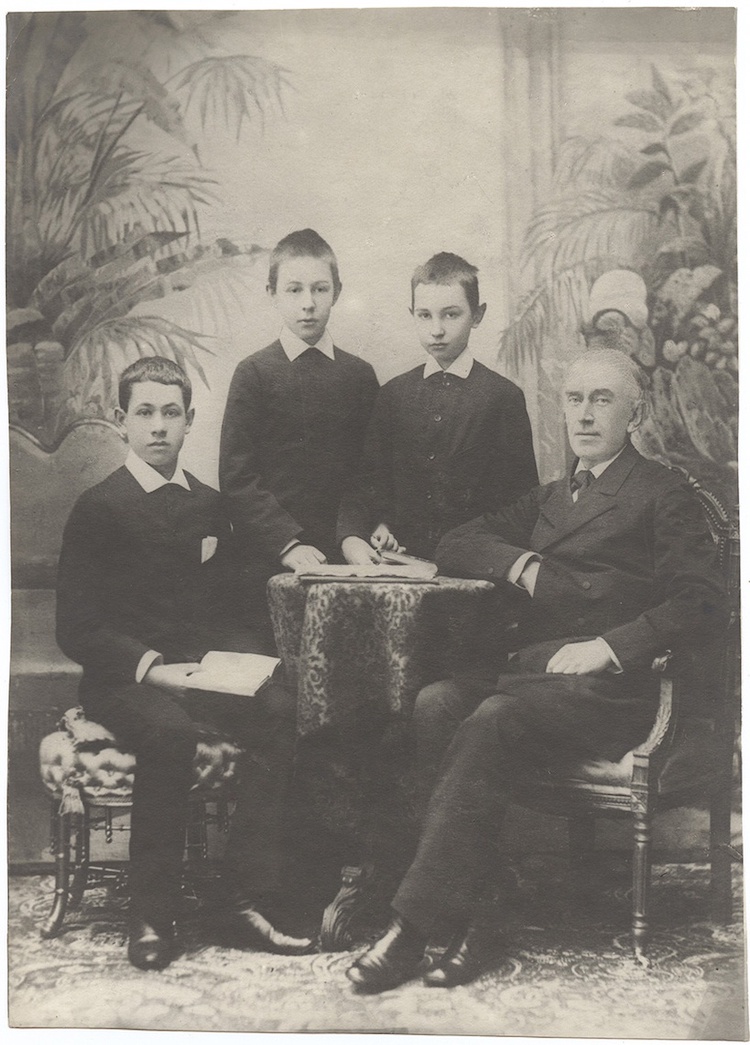

- Nikolai Zverev and his students. From left to right: Matvey Presman, Sergei Rachmaninoff, Leonid Maksimov. Photo: Russian National Museum of Music

The next three years were especially difficult for Rachmaninoff: two of his sisters died while his father left the family. Since no one looked after the young musician, he messed around, skipped classes and drew fake As in his school diary. Finally, the family council decided to transfer the slacker to the Moscow Conservatory, where 12-year-old Seryozha enrolled in Nikolai Zverev’s class and moved to his boarding house. Zverev was a famous teacher, so becoming his student was an honour for any young musician. The rules there were strict: Spartan conditions, iron discipline and complete isolation from relatives awaited Rachmaninoff. Sergei communicated with his mother only by correspondence. At the time, she was on the brink of poverty and even asked him for money, which the boy borrowed from a friend.

Read more: Composer Pyotr Tchaikovsky in London: Impressions, Recognition and Success

In the future, after the Russian Revolution, Rachmaninoff would leave for the United States, from where he regularly sent help to those in need. According to his contemporaries’ memoirs, when there were food shortages in the USSR, almost half of Moscow received parcels from the composer: sugar, cocoa, condensed milk and other products that were especially valued. Going back to Rachmaninoff’s early years, the young man’s talents were fully revealed in Moscow: in 1892, he graduated from the Moscow Conservatory with a gold medal, and his graduation work — opera Aleko based on Pushkin’s poem Gypsies — is now in the conservatory’s repertoire. Moreover, on the final exam, Rachmaninoff received an A with three pluses from his idol, Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky.

A love triangle, revolutions and emigration

From age 16, Rachmaninoff lived with his father’s sister, Varvara Satina, since Zverev kicked him out of his house for impudent behaviour. Varvara owned an estate in Ivanovka where Sergei’s relatives from his father’s side used to gather, so there, the young man found warmth and support. In the Satin family, Rachmaninoff also found his destiny: the musician’s chosen one was his cousin Natalia, who grew up before his eyes, and in 1902 became his wife. This further alienated Rachmaninoff from his mother, who his father’s relatives accused of breaking up the family. Lyubov Petrovna came to Ivanovka several times, meekly endured the attacks, and constantly prayed.

Read more: Russian Emigration a Hundred Years Ago and Now: What Unites the Two Generations?

Sergei Rachmaninoff gave the impression of a gloomy and arrogant person. Still, with his friends, among whom was the famous singer Feodor Chaliapin, the composer liked to joke and play board games and sometimes even behaved like a hooligan, just like in his youth. “Sergei Vasilievich knows how to smile?” – the guests visiting the composer, who settled with his wife in an apartment on Vozdvizhenka Street, would ask in surprise. Behind Rachmaninoff’s external asceticism lurked a sharp sense of the era, which he conveyed through his music.

- Sergei Rachmaninoff, Natalia Satina, Elena Kreutser and Natalia Lanting in 1899. Photo: Russian National Museum of Music

- Sergei Rachmaninoff and Feodor Chaliapin (1900). Photo: Russian National Museum of Music

In 1904, Rachmaninoff was already a conductor at the Bolshoi Theatre in Moscow; in 1907, he participated in Diaghilev’s Russian Seasons in Paris; and in 1909, he gave concerts at Carnegie Hall in New York, where he would later perform about 90 more times while in exile. However, at the beginning of his career, Sergei experienced a scandalous failure and lost faith in himself: on 15 March 1897, Symphony No. 1 – the first fundamental work by the 24-year-old Rachmaninoff – premiered in St. Petersburg. Critics smashed it to smithereens, although some blamed the conductor Alexander Glazunov for the unsuccessful performance. Then the composer plunged into painful silence and depression for three years, and only psychotherapist Nikolai Dal managed to help him.

Read more: Elizabeth II and Russia: A Visit to Moscow, a Box from Yeltsin and the Accounts of Eyewitnesses

In gratitude, Rachmaninoff dedicated his Piano Concerto No. 2 to Dahl. However, according to the version of the composer’s grandson, Aleksandr Borisovich, the composer did not go to Dahl for treatment but to see his daughter Lana, who became a muse and the musician’s unofficial second wife. However, Rachmaninoff’s biographers refuted this love triangle – the composer was an exemplary family man and a workaholic. Later, in 1975, Piano Concerto No. 2 was used by Eric Carmen in the process of writing the beautiful ballad All by Myself, performed by Frank Sinatra and Celine Dion. By the way, the musical theme from Piano Concerto No. 2 was also used in the song Space Dementia by the British rock band Muse, whose lead singer Matthew Bellamy is a Rachmaninoff fan.

- Photo: Kinopoisk

- Photo: Kinopoisk

Until April 1917, every year, the maestro came to work in Ivanovka (the estate was later turned into the Museum-Reserve of S.V. Rachmaninoff). He composed most of his works there, imbued with love for the motherland: 49 romances, 24 preludes, nine etudes and two sonatas. Rachmaninoff’s music reflects the Russian church bells, the breadth of endless expanses, the power of elemental forces, and the fragility of blossoming spring nature. However, with the Revolution came the “end of the world” for the composer: former Russia collapsed, and an era “without art” began.

Read more: Anna Akhmatova in the UK: A Poetess, Muse and Femme Fatale

In December 1917, the 44-year-old Rachmaninoff left Saint Petersburg through Finland with his wife and two daughters. In Russia, he had frozen accounts, a looted estate in Ivanovka and an apartment in Moscow. In his pockets, he had 500 borrowed roubles and an invitation from the King of Sweden to perform at a concert in Stockholm, which he used to leave the country. Later he moved to New York, where he worked tirelessly as a composer. Rachmaninoff’s unique hands served him faithfully: he could cover 12 piano keys at once, which equals the long side of an A4 paper sheet. Active concert activity brought the musician worldwide fame and made him the wealthiest Russian emigrant, according to his friend – poet Ivan Bunin.

Visiting the United Kingdom

In 2011, Classic FM radio conducted a poll among 180,000 Britons, according to which Rachmaninoff’s Piano Concerto No. 2 was recognised as the most popular classical work of the year, while the composer himself was named the greatest among the classics. This is not surprising because, in the United Kingdom, Rachmaninoff’s music has been loved for a long time. From May 1922, he began to come to London with concerts, and in 1938 he performed Piano Concerto No. 2 in honour of the British conductor Henry Wood at the Royal Albert Hall. Then, in February and March 1939, Rachmaninoff visited the country on a grand tour and gave 12 concerts in 25 days: the first concert took place in Birmingham on 16 February, followed by performances in London, Liverpool, Sheffield, Southampton, Middlesborough, Glasgow, Edinburgh, Oxford and Manchester.

- Photo: Bain News Service photograph collection

- Photo: Bain News Service photograph collection

The final concert of this British tour took place on 11 March at London’s Queen’s Hall, which was destroyed by German bombing two years later. Rachmaninoff performed works by European composers – Bach, Beethoven, Schumann, Chopin and Liszt – and his own compositions. The audience was delighted with Rachmaninoff’s elegant playing style and admired his magic relationship with the piano. Sometimes it seemed like it was not the pianist who sat down at the instrument, but the piano itself approached him. While playing, the maestro sang quite loudly and sat with his knees wide apart as his long legs did not fit under the piano.

Read more: Innovator and Romantic Vladimir Nabokov in Britain

After the concert at Queen’s Hall, Rachmaninoff was invited to Sydney Savage Club in London. To the composer’s surprise, he was proclaimed an honorary member of this literary club, along with Mark Twain, Charlie Chaplin and Charles Dickens. The initiator of the invitation was Rachmaninoff’s old friend, Ukrainian-born British pianist Benno Moiseiwitsch, who became a legend in the first half of the 20th century. The musicians met at a concert in New York in 1919. Since then, they have been connected by a strong friendship, their sense of irony and Moiseiwitsch’s ability to play Rachmaninoff’s works masterfully. In March 1939, in London, they saw each other for the last time: the composer promised to return with a concert in September, but his health let him down. Many noted how exhausted Rachmaninoff looked, but the composer brushed off such comments because work for him was above everything.

Sergei Rachmaninov on stage during his last concert in Lucerne. Photo: Russian National Museum of Music

In February 1943, Rachmaninoff cancelled all concerts and returned to his new home in Beverly Hills: the composer’s cancer progressed due to a long-term smoking habit. On 28 March 1943, at the age of 69, he died surrounded by relatives. The maestro was buried at Kensico Cemetery in Valhalla, half an hour’s drive from New York. With the death of Rachmaninoff, many became orphaned because he was actively involved in charity work: he helped scientists and pensioners, sent money and food to friends and acquaintances in the USSR, and, despite his rejection of the Soviet regime, made donations to the Red Army fund to support his homeland in World War II.

Read more: How Diaghilev’s Saisons Russes Influenced the European Art World of the 20th Century

During his lifetime, Rachmaninoff seemingly fulfilled all his dreams and rejoiced like a boy: he ordered expensive pianos, rode motor boats with his daughters, and bought new chic Cadillacs and Lincolns every year. He even managed to appease his deep longing for Russia by building an estate called Villa Senar on 10 hectares of land in Switzerland in the early 1930s. There Rachmaninoff finally found inspiration and wrote the legendary Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini. In 2022, the villa was sold for 8 million francs and became the property of the canton of Lucerne. Now there are plans to reconstruct Senar and include it in the UNESCO World Heritage List.

Irina Latsio

Cover Photo: Sergei Rachmaninoff in his study at Villa Senar (Russian National Museum of Music)

Read more:

Felix Yusupov and Princess Irina of Russia: Love, Riches and Emigration

Virginia Woolf and Her Fascination with Russian Literature

Dostoevsky in London and His Influence on the British Classics

SUBSCRIBE

Receive our digest once a week with quality Russian events and articles