Roma Liberov. Russian Emigration a Hundred Years Ago and Now: What Unites the Two Generations?

A century ago, at least two million people had to leave their homes forever as their lives were torn apart by the Russian Revolution of 1917 and then the Civil War, which lasted until October 1922. This is how a phenomenon now commonly referred to as the first wave of Russian emigration came to be – it was a consequence of ideological differences, fear of persecution, forcible deportations, immeasurable loss and grief. However, a hundred years later, history repeats itself, and the events of 24 February 2022 have made us unwitting witnesses to another wave of Russian emigration. But what is the difference between those who left Russia in the past and those who did it today? What unites these two generations? A year after the start of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Afisha.London magazine will try to answer these and other questions with the help of Roma Liberov and his project After Russia, which uses music and poetry to connect the two generations of émigrés whose lives were torn apart by the regime.

Today, cultural figures draw parallels between the fates of those who fled the events of 1917–1922 and those who were forced to leave their homeland because of the war in Ukraine. For example, to mark the 100th anniversary of the first wave of Russian emigration, a monumental music album After Russia came out on 13 January 2023. Thanks to Roma Liberov, the author and producer of this musical and literary project, the Russian Diaspora and, in particular, the so-called “unnoticed generation” have once again become a topic of discussion in the media. The famous Russian public figure and journalist Ilya Varlamov even made a film called The Unnoticed Generation: People Lost by Russia, which tells the stories of émigré poets “who were lost abroad a hundred years ago due to the Civil War” as well as of those who repeat their fates today. However, before turning to the present, it is essential to look back at the past and understand what the “unnoticed generation” is and under what conditions the emigrants of the first wave left Russia.

The first wave of Russian emigration: the philosophers’ ships and the unnoticed generation

A hundred years ago, the Revolution and the Civil War forced millions to leave Russia: back then, the country lost many outstanding artists, scientists, poets, writers and musicians. When thinking about the first wave of Russian emigration, the names that come to mind are Sergei Rachmaninoff, Vladimir Nabokov, Feodor Chaliapin, Ivan Bunin, Marina Tsvetaeva, Aleksandr Kuprin and Arkady Averchenko; however, among those who left Russia at that time there also were many talented people yet unknown to the general public.

- Marina Tsvetaeva. Photo: Pierre Choumoff, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

- Ivan Bunin. Photo: Maxim Petrovich Dmitriev, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

This first wave was marked by a phenomenon later called the “philosophers’ ships” – a term coined by the philosopher and scientist Sergey Khoruzhiy in 1990. In the autumn of 1922, the Bolshevik authorities forcibly expelled creative intelligentsia, scientists and cultural figures from Russia via multiple steamers and trains. Among those who boarded those ships were philosophers Nikolai Berdyaev, Nikolay Lossky and Sergei Bulgakov, as well as scientists, doctors and teachers.

One of the passengers of a “philosophers’ ship”, the philosopher Fyodor Stepun, later recalled:

“The deportees were allowed to take one winter and one summer coat, one suit, two pieces of any underwear, two day shirts, two nightshirts, two pairs of underpants, two pairs of stockings; gold items, precious stones, with the exception of wedding rings, were forbidden for exportation, even pectoral crosses had to be removed from the neck. In addition, it was allowed to take a small amount of currency, twenty dollars per person, but where to get it when prison or, in some cases, even the death penalty awaited those in possession of it.”

During the first wave, several generations of writers left Russia, though they can be conditionally divided into two separate ones – the older and the younger. The “elders” were those who bid farewell to their homeland as accomplished authors: for example, Aleksandr Kuprin, Ivan Bunin, Ivan Shmelyov and Marina Tsvetaeva. The “younger ones”, however, began their artistic journeys abroad – among them were Vladimir Nabokov, the most prominent of all, and the lesser-known Gaito Gazdanov and Boris Poplavsky. Most of the other representatives of the “younger generation” are not at all known to the general public and cannot be found in the school curriculum. Writer and publicist Vladimir Varshavsky even introduced the term “unnoticed generation” to describe those emigrants of the first wave whose paths were especially difficult and even tragic.

Russian émigrés of the first wave in the UK

Approximately 20 to 25 thousand emigrants who fled the new regime and the Civil War ended up in the United Kingdom. However, contrary to popular belief, not only nobility moved there: along with the surviving members of the royal family and Russian aristocrats, Britain welcomed generals and officers, ordinary soldiers, peasants and Cossacks. Almost none of these people knew English – those were strange shores for them. And if in Paris or Berlin, Russian emigrants could immerse themselves in their native culture – to study in Russian schools, attend Russian clubs, and read Russian press – this was not an option in Britain. Moreover, the legal status of Russian emigrants was not regulated by the British authorities. For these reasons, there were fewer refugees there than in Paris, Berlin or Belgrade.

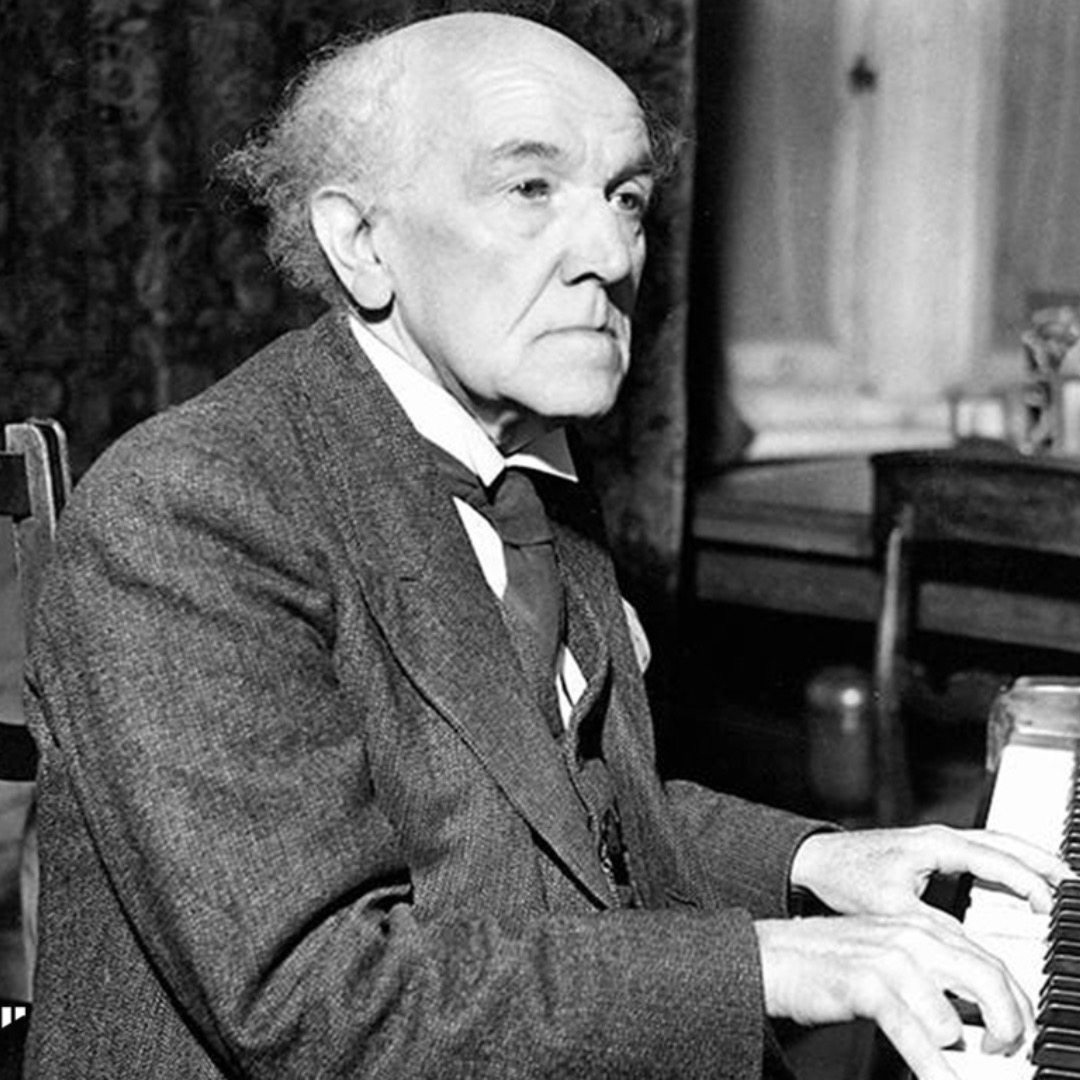

- Nikolai Medtner. Photo: nikolaimedtner.ru

- Boris Anrep. Photo: See page for author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The outstanding mosaic artist and Anna Akhmatova’s beloved, Boris Anrep, was among those who lived in the UK for almost the entirety of their exile. Some of his most famous works adorn the National Gallery, the Bank of England, Tate Britain and Westminster Cathedral in London, the Royal Military Academy in Sandhurst, and the Cathedral of Christ the King in Mullingar, Ireland. Through his art, Anrep immortalised Anna Akhmatova, Virginia Woolf, Greta Garbo, Winston Churchill and himself.

Read more: Anna Akhmatova in the UK: A Poetess, Muse and Femme Fatale

Another outstanding representative of the first wave, who became a British citizen, is the idiosyncratic pianist and teacher Nikolai Medtner. After leaving Russia in 1921, he lived in Germany and France. In 1928, Medtner gave concerts in the United Kingdom, where he received the title of honorary member of the Royal Academy of Music. Seven years later, in 1935, he finally moved to London. However, despite his success and recognition in the UK, Medtner was homesick. In one of his last letters, he wrote: “I dream of going back to my native lands and playing in front of my native audience.”

Vladimir and Vera Nabokov, 1969. Photo: Giuseppe Pino (Mondadori Publishers), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Of course, when discussing the first wave of Russian emigrants who moved to the UK, it is impossible not to mention the most prominent writer of that generation – Vladimir Nabokov, who is conventionally referred to as part of the mentioned above “younger” or “unnoticed” generation. Nabokov, immersed in English literature and culture as a child, left Russia at the age of twenty with his parents in the spring of 1919. This was before his name had a chance to become widely known.

Later, having already become a famous writer, Vladimir Nabokov recalled in his memoirs Other Shores:

“On the small Greek ship Nadezhda (rus. hope), returning to Piraeus with a cargo of dried fruits, we left the Sevastopol Bay in early April. The port had already been captured by the Bolsheviks, there was indiscriminate firing, and its sound, the last sound of Russia, began to fade, but the shore was still flashing either with the evening sun reflected in the glass or with silent, distant explosions, and I tried to concentrate my thoughts on the chess game that I was playing with father…”

Once in London, Vladimir Nabokov enrolled at the University of Cambridge, where he studied entomology and literature. During his studies, he also wrote poetry and translated various texts. Moreover, under the pseudonym Vl. Sirin Nabokov published an essay called Cambridge, in which he described his trials and homesickness, in the émigré newspaper Rul’ (rus. steering wheel), where his father was the editor.

Read more: Innovator and Romantic Vladimir Nabokov in Britain

When Nabokov’s parents moved to Berlin, he stayed in the UK to complete his studies. However, in the spring of 1922, when the young writer came to his parents for the Easter holidays, his father was killed while trying to protect the ex-Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Provisional Government, Pavel Milyukov, during a performance at the Berliner Philharmoniker. The death of his father was a great shock to Nabokov. He returned to Cambridge and, after graduating with a bachelor’s degree, left England and moved first to Berlin, then to France, before settling in the USA. Incidentally, Nabokov stopped writing in Russian at the end of the 1930s and gained world fame as an English-language author.

After Russia: rhyming the epochs

After Russia is a musical and literary project in which such artists as Noize MC, Monetochka, Nogu Svelo!, Pornofilmy, Naum Bleek and others, many of who left Russia after 24 February 2022, are building a cultural bridge to a century ago. To the time when an entire generation of Russian writers lost touch with their homeland and remained “unnoticed”. The album, which has the same name as Marina Tsvetaeva’s poetry book published in 1928, includes 16 tracks with poems by Vladimir Nabokov, Yuri Mandelstam, Georgy Ivanov and other émigré poets in place of lyrics.

- Album cover

- Roma Liberov. Photo: Facebook

The most important thing to know about After Russia is that all the songs featured on the album are connected. This is a monumental story that needs to be listened to in its entirety – from beginning to end. Roma Liberov asked his friend Polina Proskurina-Janovich to help him select the texts to be used as lyrics. Together they read entire volumes and compiled lists while searching for something that correlates with today’s events.

“This is not a political manifesto. We are not passing judgment on an era but trying to find consolation. After Russia is mercy, the poetry of silence, sleep and hope, which allows one not to feel alone in this separation,” – says Roma Liberov.

Roma Liberov: “You did not disappear, we read you!”

Roma has not been to Moscow for more than a year, and during our conversation, he was in Tel Aviv. The last projects he managed to finish in Russia are a film based on the works and biography of Andrei Platonov, The Secret Man, and a tribute album marking the 130th anniversary of the birth of Osip Mandelstam. The latter was recorded with such musicians as Oxxxymiron, Ilya Lagutenko, Leonid Agutin and many others. For Roma Liberov, who is currently in exile, After Russia has become part of his personal history.

— It all started with a terrible tragedy, so from the first notes, Max Pokrovsky (lead singer of Nogu Svelo!) bursts into this story and smashes everything to smithereens – he sings about the industrial production of death during the First World War. Then we hear Vadik Korolyov’s and Zhenya Popova’s composition that resembles an Orthodox service, the sound of which carries over the fields of the fallen: “Bullets, bullets, bullets, fell, fell, fell…”. This is followed by an outstanding track by the band NAÏVE based on Vadim Andreev’s poem Machine Gun. Next up is a “funeral service” Fading Shore, by folk singers Misha Dymov and Mila Varavina – this is the sound of evacuation, of the beginning of emigration. And after that comes Naum Bleek’s “emigrant rap” about sleep and love in a squalid attic under a Parisian roof: “The window leans like this: window, windows …”.

Nogu Svelo! Photo: Ksenia Pavlova

— While working on the album, I involved those familiar with the feeling of separation from their homeland: it does not matter if it is temporary or permanent. The artists were in pain, and some disappeared before the project was finished. Frankly, some were afraid to be in the same project with those labelled foreign agents in Russia.

Read more: How Diaghilev’s Saisons Russes Influenced the European Art World of the 20th Century

— Almost no track on the album was conceived quickly, except perhaps Afar by RSAC – a song of stunning beauty that immediately “flew” just like the butterfly from Georgy Raevsky’s poem: “But, escaping with silent laughter, it flew up towards the blue.” A very limited circle of people knew about the forthcoming album. And then, one day, an outstanding journalist, our senior comrade, Leonid Parfyonov, called me and said: “Roma, you definitely have to include, you hear me, you definitely need these lines by Nabokov: ‘There are such nights when as soon as I lie down, the bed floats to Russia, and then they are leading me to a ravine, leading to a ravine to kill’”. This is how the song The Shooting, fantastically performed by Monetochka, was born.

- Monetochka. Photo: Instagram @monetochkaliska

- Felix Bondarev from RSCA. Photo: @felixbondarev by @allsehend_photo

— I think we managed to achieve something with this album. Let it become a testament to the era. If there were such a seance where these poets would hear us, I would like to shout: “You have not disappeared anywhere, we have read you!”.

Naum Bleek: “Home and Motherland have ceased to be a single entity”

One of the artists who immediately agreed to take part in the recording of the album was the poet and musician Naum Bleek. Bleek decided to leave Russia relatively quickly, but it was a difficult choice because, despite his oppositional views, he was not going to leave his homeland until the events of 24 February 2022.

— I thought for a month, and then went to Kyrgyzstan, to Bishkek. There I began to prepare to move to France. Before that, I could not even imagine that I would leave Russia – I wanted to work at home and write poetry and music in my native language environment. So the fact that I left is both a forced decision and an expression of my anti-war position.

Naum Bleek. Photo: afterrussia.world

— I ended up in Paris thanks to Atelier des Artistes en Exile, an organisation that helps creative people from all over the world settle down in France. Its studio for émigré artists unites people from Russia, Ukraine, Iran, Afghanistan, Palestine, Kyrgyzstan and other countries: artists, musicians, dancers, writers and poets work there. Moreover, it helps organise concerts and performances, gives legal advice and helps in every way possible to settle in a new place. This is such precious help because emigration, especially forced, is difficult. I have lived in Paris for more than half a year, and in the past three and a half months, I have moved nine times.

Read more: Emmeline Pankhurst in St. Petersburg: The Suffragette Movement in Britain and Russia

— When Roma Liberov offered to take part in the recording of the album, I immediately agreed. Those who emigrated a hundred years ago and Russian emigrants of today have much in common. It is homesickness, the collapse of hopes and previous life, and a forced need to change everything. Many today, like people in the past, have to learn a new language and do work unrelated to their professional activities – including washing floors or cooking in kitchens, as I am now at Burger King. At the same time, today, we have the Internet, bank cards, Google Translate and the opportunity to work remotely. We must admit that in this respect, it is easier for us. It is very hard to come to terms with the fact that home and homeland have ceased to be a single entity, but you gradually get used to it. These concepts coincide when you live in Russia, but today for me, they began to separate. And now I am looking for this new home.

In the last century, representatives of the “unnoticed generation” worked as taxi drivers, washers, and loaders; they starved, lived on the streets, died young, and only a few met their readers at home. But nowadays, communication with the homeland and the opportunity to earn money through one’s art remain: modern technologies leave practically no chance for the emergence of a new “unnoticed generation”. So today, a hundred years later, we are talking about a roll call of destinies, behind which are the tragedies of real people who have lost their homes and have not yet found new ones.

After Russia was released at the beginning of 2023, and is available on all streaming platforms.

Cover photo: collage Afisha.London

Read more:

Dostoevsky in London and His Influence on the British Classics

Virginia Woolf and Her Fascination with Russian Literature

Composer Pyotr Tchaikovsky in London: Impressions, Recognition and Success

SUBSCRIBE

Receive our digest once a week with quality Russian events and articles