Anastasia Witts: “There is no art above politics”

The war in Ukraine has been going on for more than 120 days, and during this time it has become something ordinary, a part of our life. However, hundreds of thousands of people in Ukraine and refugees in European countries suffer every day from military action, displacement and humanitarian crises. To remind Londoners of the ongoing war, The Voice of Russia initiative, in collaboration with the Art Against War Telegram channel, presents an exhibition of anti-war artworks by the Russian artists and illustrators in the London Underground. Afisha.London magazine spoke with the project producer Anastasia Witts about the purpose of this exhibition, the featured artists and the possible future projects.

— Tell us a little about yourself, please. Have you always worked in the art world?

— Not always. I came to the UK for the first time in 2003 and in 2004 I moved here, so I’ve been living in Britain for pretty much a half of my life. I have background in linguistics and music. At the same time, I had lots of experience in web design and new technologies at the very beginning of the 21st century, when the internet was in its infancy in Russia. I was lucky enough to work on the first web presence in Russia of such companies as Samsung, Hewlett-Packard and Nokia etc, we were creating what we now know as the Russian Internet. Since moving to Britain, I have been teaching web and graphic design, informatics and other technology courses. But I was always drawn to art and music, and gradually became an independent producer of cultural projects. Since 2010 I have created a number of my own, such as OperaCoast, No Voice Unheard, AltPitch Festival. I have also founded a digital communication agency Artist Digital. But since the beginning of the war, although I had no practical need to drop everything and do anything differently, emotionally I simply could not continue my business as usual without joining the anti-war movement. And thus, we created The Voice of Russia — Russians Against the War.

Photo from the personal archive of Anastasia Witts

— What does The Voice of Russia do?

— We have two main goals. One is to reinforce and amplify the anti-war message that comes from Russian speakers both from Russia and the rest of the world. We also work on keeping and strengthening the ties with the European community, to prevent the Russians from being cut off from the European cultural environment.

— How did the Art Against War exhibition in the London Underground come about? How did you find out about this Telegram channel?

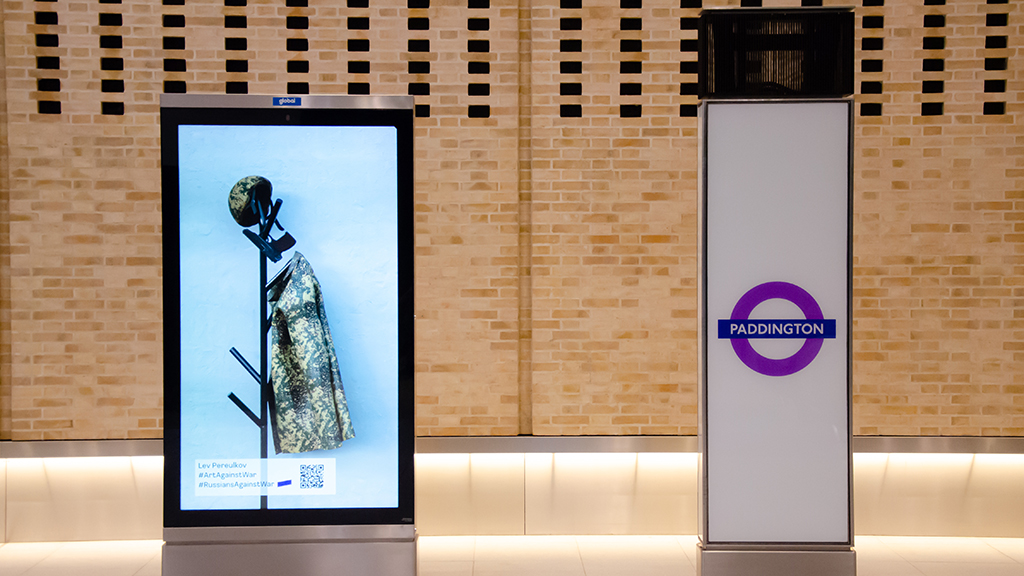

— The idea of the project was mine. Art is one of the most powerful mediums for amplifying any message. And I wanted to show people in the UK how Russian artists see this situation. And I wanted it to be shown in unlikely places. This is the reason why the exhibition takes place at the railway stations and in the London Underground. A railway station provides a symbolic connection with those people who were forced to flee their homes in Ukraine, who were forced to flee from Russia too. It is such a symbol of displacement. (For example, a monument Kindertransport – The Arrival, dedicated to children who fled Nazi persecution, was erected at Liverpool station, and a monument to the Windrush generation was recently erected at Waterloo station — Editor’s note.).

- Kindertransport – The Arrival. Photo: Life in Megapixels

- Monument to the Windrush generation. Photo: Department for Levelling Up, Housing & Communities

Then I began to look for the content for this project. It turned out that a person I know very well — Clementine Cecil, who was the director of Pushkin House at some point, and her good friend Alexandra from Russia started this Telegram channel together. It was created in order to preserve this immediate reaction by the artists, people with high sensitivity to what is happening. The uniqueness of this channel is that it publishes not only the works by the Russian artists, but also the works by Ukrainian and Belarusian artists, as well as artists from other countries. We called out, some artists responded, and we made this exhibition. It would have been great, of course, if we had enough resources and an opportunity to show more than just the 15 works that ended up in the shortlist.

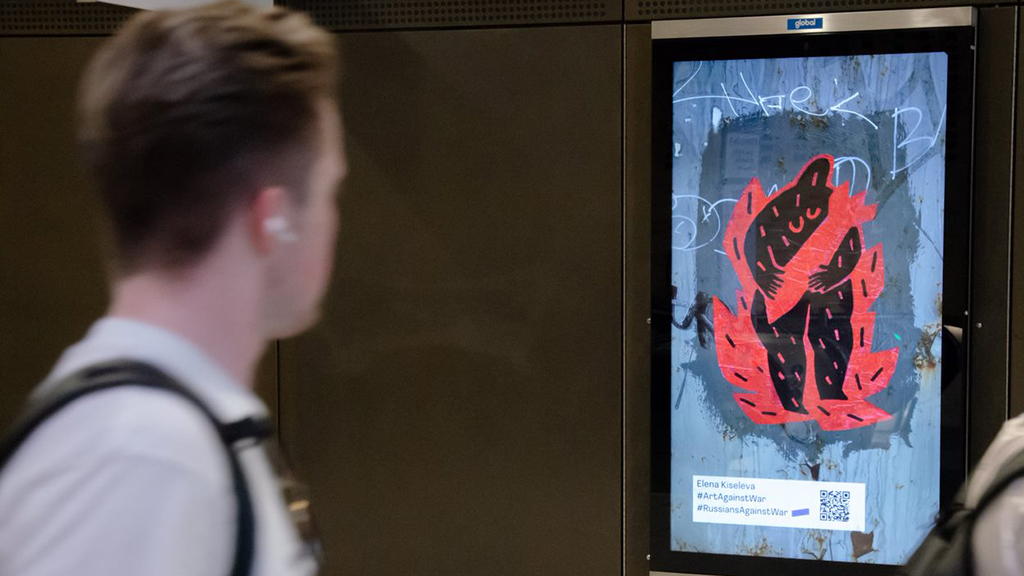

— Where can you see these works?

— At Victoria and Paddington railway and underground stations. There are also some screens at Charring Cross, Waterloo and Piccadilly Circus. There are 15 screens in total.

- Sasha Konakova

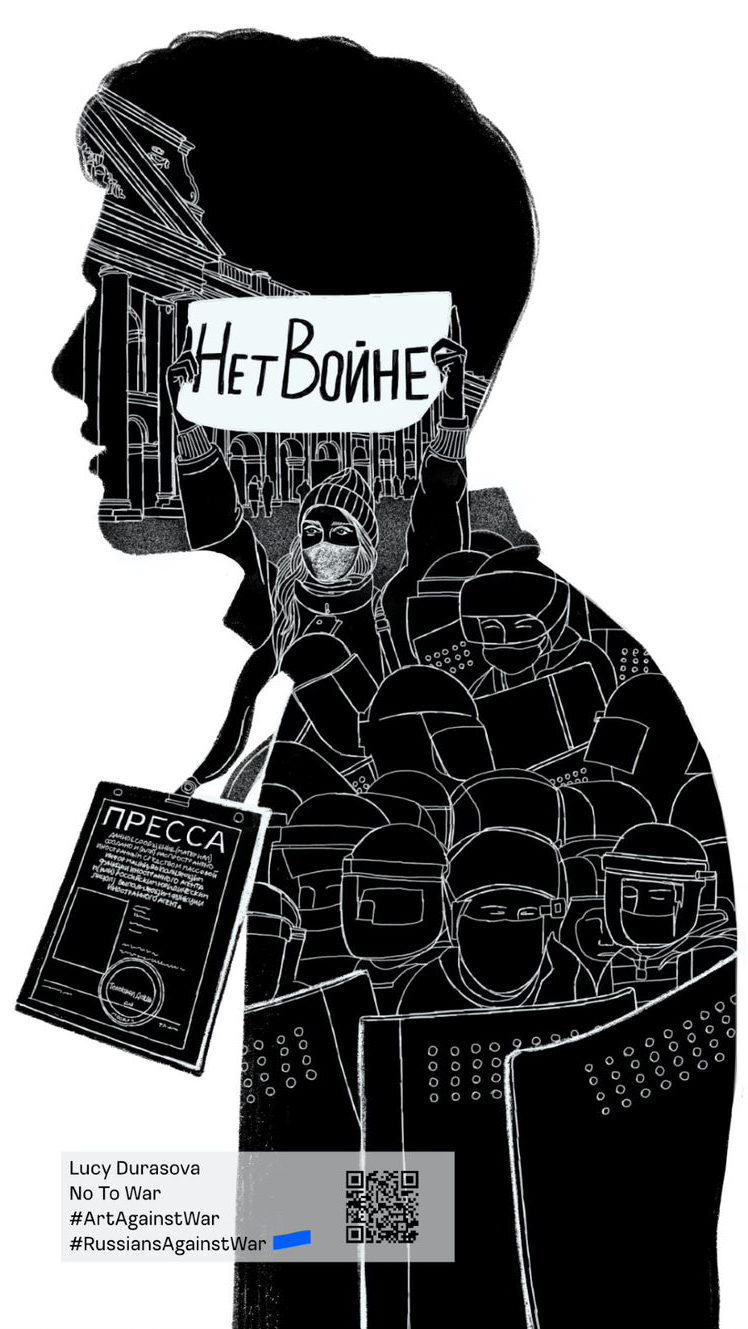

- Lucy Durasova

— On what basis were you given these spaces?

— On commercial basis, of course. When I shared this news with some contacts in Moscow, I didn’t expect to hear that they assumed it was free. It turned out that we have some significant cultural divergence. In Moscow, apparently, you can get billboards in the metro for free to show some kind of social advertising. But this is precisely the vehicle for the state propaganda. In the UK, however, such an opportunity can only be obtained on commercial terms. But even then, we might not have been able to do this without one absolutely delightful coincidence. We, of course, don’t have any large funds, we only rely on some private donations by people who support our cause. I’d spent a month trying to get somewhere but to no avail. Then I sent an email to Global — the agency that does advertising for the London transport infrastructure and received a response very promptly. It turned out that the agent who happened to come across my email had a wife from Ukraine, and now her relatives live in their house as refugees. This is a true serendipity indeed and I am very grateful to Chris who helped us to realise this project.

Follow us on Twitter for news about Russian life and culture

— What is so important about this project? What should it motivate people for?

— We are all becoming very accustomed to war. We don’t feel it, but it’s terrible. It affects our psychology, as individuals, as well as a society. We are becoming desensitised to everyday tragedies; we often try to live as if nothing was happening. And most importantly, it is almost impossible to prevent this desensitisation — it is a natural process. And yet, right now, as we speak, in Lisichansk people are being shelled. How can you possibly connect these two realities in one’s mind? That’s why I find it important to be reminded about what is happening. This is necessary for those people who will be passing by on their morning commute, to all of us just to remain human. We need to remember that people like us are under shelling somewhere, people like us have lost everything. People like us don’t know where to go because they are in a refugee camp somewhere in Poland and they have absolutely nothing left. They can go anywhere but the only place they want to go to is home, while home is no more. We must think about it to retain our human responses. And also to do whatever we can do trying to bring the end of this war closer. Because it must end. It should never have started.

Photo: Miles Berkley-Smith

—How did you select the artworks for this project?

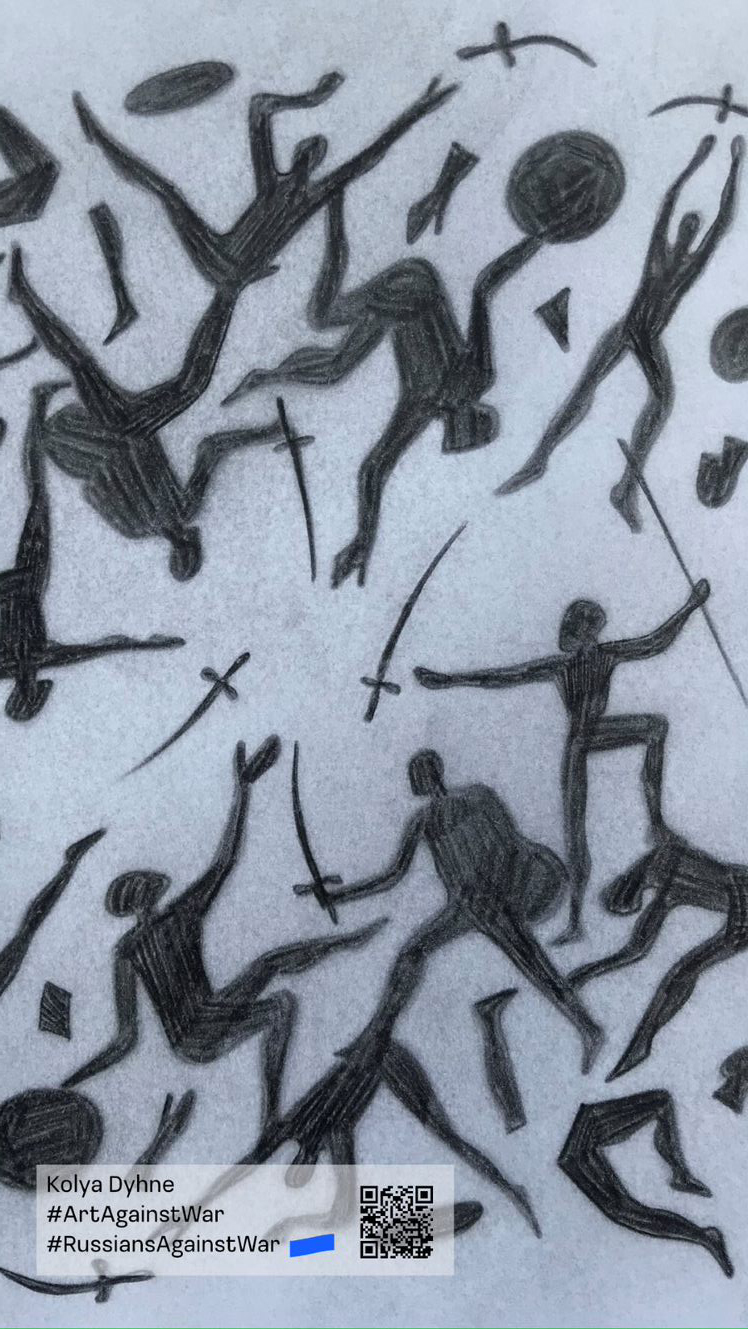

— We sent the word around on the Art Against War Telegram channel. We were ready to accept artworks from anywhere, but mostly Russian artists responded. We have one artist from Ukraine, to whom I am very grateful for sending us her work. We wanted to choose those images that showed the anti-war message loud and clear — that was the main criterion. We wanted to make the project inclusive: to give an opportunity to people who do not have any fame or a big name, to express what they want to express publicly. We had many artworks — many times more than the number we could use with our limitations. And, of course, the London Transport Network has its own regulations: we couldn’t show any depiction of blood, violence or weapons. This, of course, is paradoxical: showing war without showing any signs of war. But this, I think, is the power of art — it is capable of conveying the message no matter the limitations.

— Is there any plans to extend this project and, perhaps, to show more than what was possible in the London Underground?

— I would love to turn it into an exhibition somewhere where people could come purposefully. The original purpose was to mix the artworks with advertising, to make it a part of daily life where we may not even notice the horrors that we know are happening. But I would like to be able to shift the focus over to those people who are involved in this project. To those artists who live with this need to protest against the war within the society where many people support it. It seems to me a very strong motivation, and I’d really want us to have the chance to talk about it. I would be very happy to hear from a gallery or some other place where we could place these works on a non-commercial basis. As Russians living in Britain, we must be very vocal about our opposition to the war. This is extremely important, first of all – to us. I am sure that for the rest of our lives we will all be judged in one way or another by what we are doing right now. And this gives me the strength to go on, to continue working, although psychologically it can be quite difficult.

Photo: Miles Berkley-Smith

— Do you think art must fight for freedom? Should it reflect reality, or maybe it should somehow distract from what is happening?

— Art is only a tool. And as with any tool, it does not necessarily contain any embedded ethos for which this tool should be used. If you have a hammer you can build a beautiful house, or you can destroy this house with the same hammer. It would be wrong to say what, in principle, art does or should do, it does not owe anything to anyone. But the significance, the relevance and the purpose of any art depend on who is using it. For me personally, art cannot be relevant without being tied to reality. Art should be for the sake of life and people, and not for its own sake where is becomes simply decorative. I support and admire those initiatives, in any genre, that, especially now, do not shy away from the reality in which we live, but openly face it and try to work with it. Because without poetry, paintings, music, we will not survive the tragedy that is happening right now with so many people in the world. If it is at all possible to heal and work through such trauma, then it will only be possible through this medium, by translating this trauma into the poetic, metaphorical sphere. And art must take responsibility for this mission.

— What do you think about the restriction in the art world between different countries? It has always been said that art and sport should be above politics, but the last couple of decades have proven otherwise.

— There is no art above politics. Everything in our lives is, ultimately, about politics. Whoever is trying to convince you otherwise is either naïve or manipulative. If we say that art should reflect reality, then to follow with “art is above politics” is illusionary. The fact that in Ukraine they ban Russian-speaking sources is perfectly understandable, we have no right to judge it. You cannot be subjected to a horrific aggression by another country and allow people who deny this aggression to be on the scene. Ukraine has a very rich culture that could not develop to its full glory for quite some time – it was not supported by the state in the Soviet Union. And when Ukraine became an independent state, the development of its culture became a very important principle of this independence. Now we have an opportunity to see the Ukrainian culture as we have never seen it before – rich and unique. So now we should try and learn more about it.

If you call yourself an artist, you must have a view, must take a position. In Russia and some other countries, art is fully subsidised by the state. In this case the state uses the arts to dictate and promote its own agenda. In Russia’s case, we are talking about a very heavy propaganda that affects people psychology, forms generations, shapes the mentality of the nation. If people of art are engaged in shaping of the nation’s mentality, they should be accountable for it. In the time of the war, it’s pretty straight forward, really – one just have to say, including via their art, that it is unacceptable to kill people, that killing people is monstrous.

- Kolya Dyhne

- Pavel Otdelnov

— What kind of feedback do you expect from the project and what would be a sign of success for you?

— It is very important for people to be able to stop and think. If anyone wrote to me or one of my colleagues and said: “thank you, it was thought-provoking”, “we got it”, it would be warming. But the most important purpose is to make people think. If we could manage to extend what we do (and this is not our only project) a little further, to show it to more people, to find enough resources to complete the projects we started, we would be happy, of course. And we would always accept help: finances, useful contacts, volunteering… But big thank you also to Afisha.London magazine for helping to highlight this project to a wide audience. If we are the voice, then the media is our microphone. It is very important to us to be heard.

Cover photo: Miles Berkley-Smith

Read more:

Pushkin House announces shortlist for its 10th Pushkin House Book Prize

SUBSCRIBE

Receive our digest once a week with quality Russian events and articles