Bakst, Benois and Dobuzhinsky: How an Extensive Collection of Russian Art Ended Up in Oxford

Oxford is primarily famous for its university, which is not only one of the world’s most prestigious higher education institutions but also one of the oldest. However, it is not the city’s only attraction – it also houses a fantastic museum that contains an unsurpassed collection of Russian art. Afisha.London magazine examines the cultural ties between Oxford and Russia and recounts how one of the largest collections of Russian art in the world appeared in the Ashmolean Museum.

Oxford as a Stronghold of Russian Art and Education

For many centuries, Oxford has been a centre of attraction for immigrants from the Russian Empire, the Soviet Union and then Russia. Over the years, students, scientists, artists and even rulers visited this historic English town, some of whom also worked, studied, performed or gave lectures in the oldest university in the English-speaking world: among them were Peter the Great and Alexander I, Anna Pavlova, Vladimir Nabokov and Leonid Pasternak, Anna Akhmatova, Iosif Brodsky, Ivan Turgenev and Dmitry Mendeleev.

There were also many Russian students at Oxford, but only wealthy aristocrats who knew English well could afford such a luxury. Their student life was not easy: some became seriously ill, while others could not fully pay for their education and were in danger of going to prison because of debts.

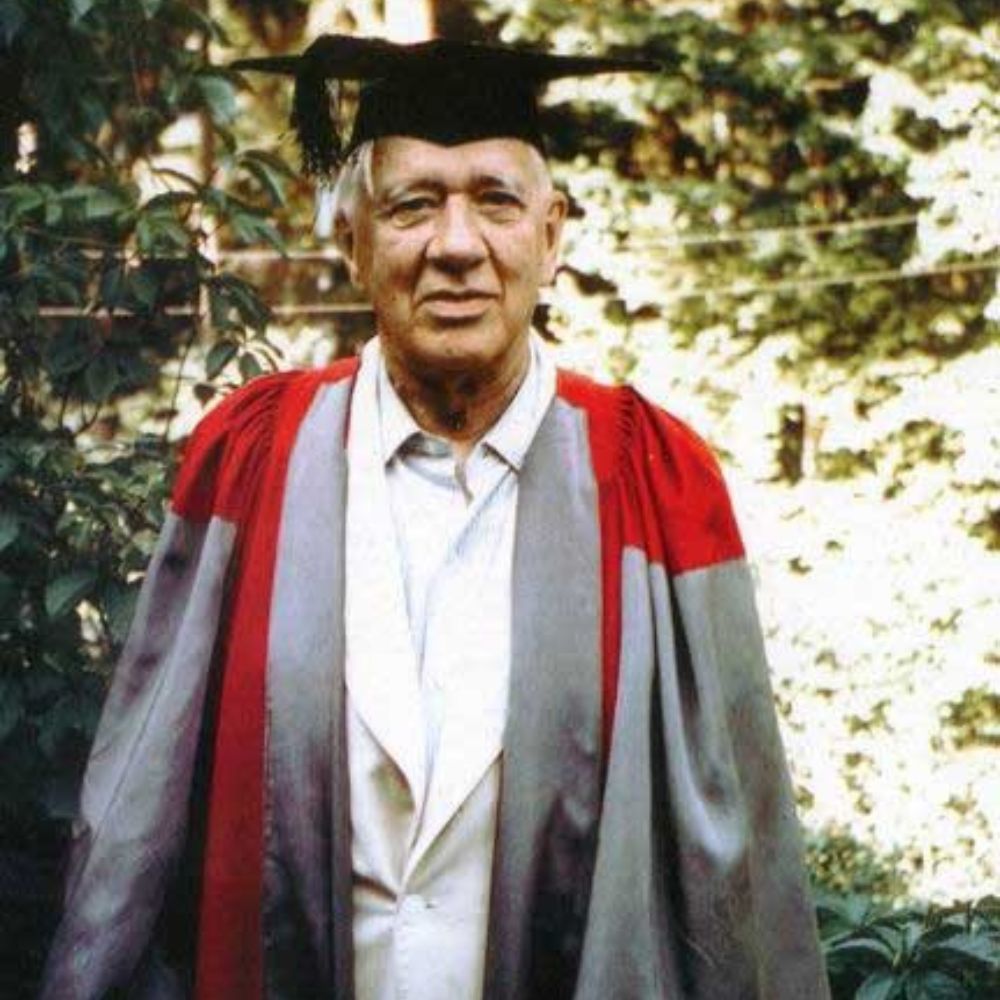

- Korney Chukovsky in the robes of a doctor at Oxford University, 1963 / Photo: K. I. Chukovsky House-Museum

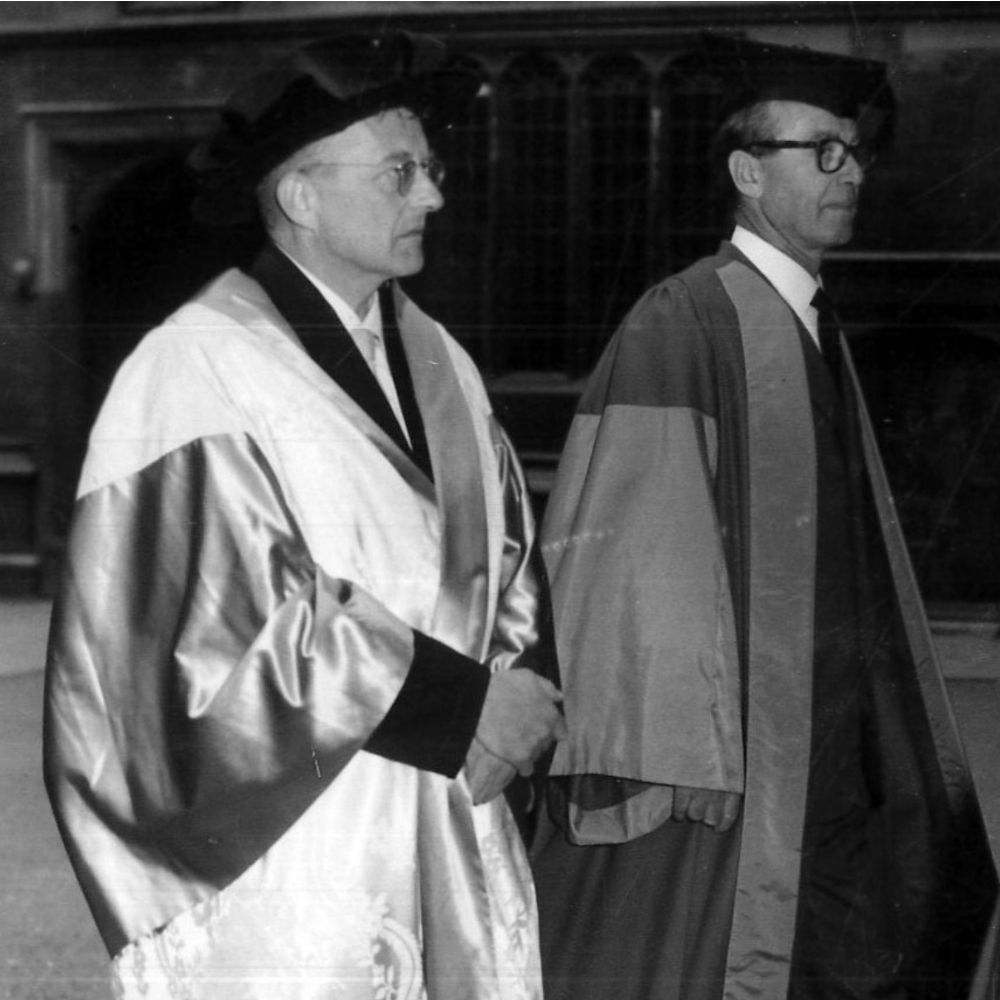

- Shostakovich and Arne Tiselius approaching the Sheldonian / Photo: Oxford University Archives, VC 3/1/7

After the Revolution of 1917, Oxford became not just a place where one could get an academic education but also a stronghold of the Russian emigre community. Later, after the Second World War, it also began attracting political figures. At the time, many scientists and artists from Russia received doctoral degrees from the University of Oxford: among them were Korney Chukovsky, Dmitri Shostakovich, Dmitry Likhachev, and Andrei Sakharov. Then, after the fall of the Iron Curtain, in the late 80s, an even bigger stream of Russians poured into Oxford. Today, ‘traces’ of Russian culture can be found in local libraries, archives and museums, including the Ashmolean Museum.

Read more: Innovator and romantic Vladimir Nabokov in Britain

Who is Elias Ashmole, and Where Does His Collection of Curiosities Come From?

Elias Ashmole was born into an impoverished family of saddlers, and in 1633 he came to London to become a solicitor. His career led him to the post of the royal tax collector and then to the position of the head of the ordnance service at Oxford.

Ashmole diligently studied mathematics, chemistry, alchemy, numismatics and astrology. At the same time, his acquaintance with George Tradescant the Younger, a hereditary botanist and naturalist who collected curiosities, as well as his father’s love for travel, which Elias also possessed, gave way for a creation of a massive collection of unusual items that he brought from his trips. It is worth noting that there is a similar collection in Russia – the Kunstkamera, founded by Peter the Great in St. Petersburg. It is quite possible that the idea to create a ‘cabinet of curiosities’ in Russia came to Peter right after he visited Oxford.

- Elias Ashmole by John Riley / Photo: Wikimedia Commons

- Ashmolean Museum now / Photo: facebook.com/ashmoleanmuseum

In 1652, Ashmole compiled a complete catalogue of Tradescant’s exhibits and published it at his own expense. The botanist, in gratitude, bequeathed his entire collection to Ashmole, and he, in turn, having accumulated enough money and increased the collection, transferred it to Oxford University. A museum that received the donor’s name was built to house this vast array of valuables.

Foundation of the Museum and Its Funding

The Ashmolean Museum opened in 1683. The collector gave all his treasures to Oxford University on the condition that they be placed in a separate purpose-built building. The new museum was not just an exhibition space – it was a scientific institution with a chemical laboratory and classrooms for students, and, most importantly, from the moment it opened, this storehouse of knowledge was open to the general public.

Read more: Roma Liberov. Russian Emigration a Hundred Years Ago and Now: What Unites the Two Generations?

At first, the museum was located in a small building, but in the 19th century, it moved to a new space. At the same time, the original collection, which included antique coins, books, engravings, minerals, stuffed animals and much more, was disbanded, so the Ashmolean Museum began to specialise in painting and archaeology.

In the museum’s collection, one can find a considerable number of paintings by world-famous artists: Albrecht Dürer, Leonardo da Vinci, Raphael, Michelangelo, William Turner and John Ruskin. Also, one of the most famous rarities stored at the museum is the Messiah – a violin made by Stradivari. However, the museum’s centrepiece is a collection of Russian paintings and drawings.

Mikhail Braykevich: How Russian Paintings Ended Up in London

Mikhail Braykevich was an engineer, port designer and statesman from Odessa who, like many other educated people at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, was fond of the exact sciences and art. He owned one of the best collections of paintings and drawings of the Silver Age, and among his friends were many successful artists of that time: Benois, Vrubel, Dobuzhinsky, and Somov.

When emigrating to England, Braykevich left his collection in Odessa. Still, he could not live without art, so he compiled a new one in London. Mainly, it consisted of paintings by Braykevich’s friends, the artists of the World of Art circle, who also ended up in exile after the Revolution. By his order, some new pieces and duplicates of those that remained in the USSR were created.

Read more: How Diaghilev’s “Saisons Russes” influenced the European art world of the 20th century

Most of the collection was Somov’s landscapes, still lifes and watercolours, the subject of which was ballet. Alexandre Benois presented the patron with theatrical sketches, including those created for Diaghilev’s opera The Nightingale by Igor Stravinsky. Bakst contributed portraits of Isadora Duncan and Andrei Bely. At the same time, Valentin Serov shared portraits of Countess Musina-Pushkina and Helena Ivanovna Roerich.

- Portrait of Isadora Duncan dancing by Léon Bakst / Photo: © Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford (image)

- Design for Anna Pavlova’s Costume of Columbine in ‘Arlequinade’ by K. A. Somov / Photo: © Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford (image)

In 1940, Braykevich donated his collection to the Ashmolean Museum, where it is kept to this day. Among other ‘donors’ of Russian art was the doctor Tatiana Gurlyand – she presented the museum with Korovin’s landscapes View of Paris at Night and Autumn Leaves, Serov’s sketch Hunger, Somov’s sketch of the costume of Colombine for Anna Pavlova, and other works.

The Ashmolean Museum constantly expanded its collection and acquired or accepted as a gift more and more new works by Russian painters. Today it is one of the largest collections of Russian art outside Russia, and the museum regularly hosts exhibitions and themed educational events dedicated to Russian artists.

Cover Photo: Ashmolean Museum

Read more:

Lewis Carroll in 19th-Century Russia: Monasteries, Theatres and Russian Shchi

Nicholas II and George V: A History of Friendship and Duty

Dostoevsky in London and his influence on the British classics

SUBSCRIBE

Receive our digest once a week with quality Russian events and articles