Leo Tolstoy in London: shaping the British literary landscape

Regarded as one of the most influential novelists and philosophers at the cusp of the 19th and 20th centuries, Leo Tolstoy’s authority was rivalled only by that of Emperor Nicholas II. His seminal works, ‘War and Peace’ and ‘Anna Karenina,’ have found a particularly devoted following in the United Kingdom. A decade ago, British cinema celebrated this affinity when director Joe Wright premiered his theatrical rendition of ‘Anna Karenina,’ elegantly melding Russian classicism with Britain’s penchant for the dramatic. To commemorate both the anniversary of this groundbreaking film and Tolstoy’s birthday, Afisha.London magazine delves into the Russian writer’s intriguing relationship with Victorian London. Tolstoy not only visited the British capital but also forged friendships with significant figures such as the revolutionary publicist Alexander Herzen. A frequenter of London’s elite gentlemen’s clubs, Tolstoy even entertained the idea of emigrating to England

Tempter, saint and genius

Born on 9th September 1828 to Count Nikolai Tolstoy and Princess Mariya Volkonskaya, Leo Tolstoy’s early life was rooted in the estate of Yasnaya Polyana, located in Tula Province. Throughout his life, the estate served as a poignant connection to his mother, who passed away when he was just shy of two years old. Tragically, no adult photographs of Mariya have survived, compelling Tolstoy to construct an idealised image of her in his own mind, envisioning her as the epitome of beauty.

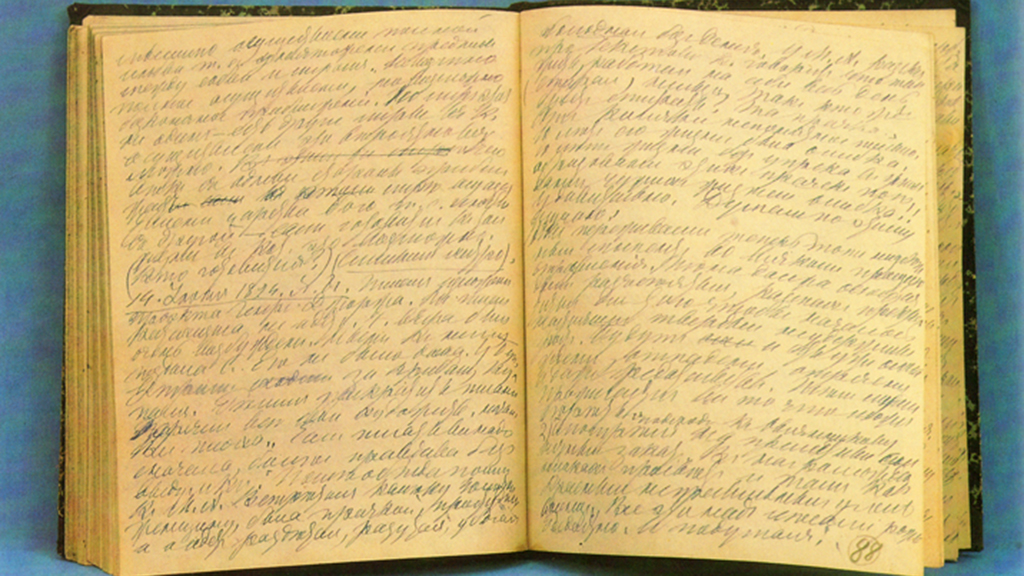

Perhaps it was this idealised image of his mother that led Tolstoy to develop a somewhat condescending attitude towards women in his later life. Despite probing the complexities of female nature in works like ‘Anna Karenina,’ Tolstoy appeared unable to reconcile himself with the earthly passions of women, even though he himself was a man of considerable emotional depth and contradiction. From a young age, Tolstoy meticulously documented his romantic entanglements in personal diaries. According to literary scholars, this confessional practice may have been an attempt to alleviate the guilt he felt for succumbing to vice. In a shocking act, he would later share these intimate journals with his young wife Sophia, leaving her profoundly affected for the rest of her life.

Read also: Joseph Brodsky in London: from Soviet outcast to professor at the West’s top universities

The house where Tolstoy was born, 1828. Photo: P.Preobrazhensky, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

After the untimely death of their father in 1837, the Tolstoy children were placed under the care of distant relatives. The family relocated from Yasnaya Polyana to Moscow, and later to Kazan. Here, Leo and his brothers enrolled at the Imperial Kazan University. Tolstoy’s autobiographical trilogy—’Childhood, Boyhood, and Youth’—reflects the turbulent experiences of these formative years, already delving into recurring themes in his later works: morality, the quest for life’s meaning, and the inner battle with oneself. In 1847, Tolstoy returned to Yasnaya Polyana, which he took possession of as part of his inheritance. Of all his siblings, Leo alone expressed the desire to continue the family line. He fulfilled this ambition when, in 1862, he wed 18-year-old Sophia. Their marriage endured for 48 years and saw the birth of 13 children.

- Tolstoy in the uniform of a Crimean War participant, 1856. Photo: Sergey Lvovich Levitsky, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

- Photo: Afisha.London/Midjourney

Though Tolstoy is often regarded as a homebody, his years before settling into marital life and taking the reins of the family estate were punctuated by extensive travels both within Russia and across Europe. Caught in a dichotomy between innate introversion and an urge to make a splash in high society, Tolstoy led an animated social life in Moscow and St. Petersburg from 1848 onwards. His pursuits included gambling as well as indulging in the music of Handel and Chopin. However, it was his published accounts of the Crimean War—particularly his firsthand experiences during the defence of Sevastopol in 1854—that catapulted him into the limelight.

Diary of Leo Tolstoy

Visiting Herzen in London

In St. Petersburg, Tolstoy found himself in illustrious company, sharing an apartment with fellow Russian literary giant Ivan Turgenev and forging friendships with figures like Nikolai Nekrasov. Despite this glittering social circle, Tolstoy’s restless spirit grew increasingly disenchanted with the frivolities of high society. Compelled by this inner turmoil, he embarked on a European sojourn. During this journey, he found himself disheartened by the stark divisions of wealth and poverty that segmented the population, a contrast that would inform much of his later writing.

Tolstoy’s second European sojourn was motivated by a specific objective: to familiarise himself with Western educational methods with a view to incorporating them at the Yasnaya Polyana school. In February 1861, he spent nearly a month in London, a stay that would prove seminal for him. It was during this time that he had the opportunity to meet his long-admired idol, Alexander Herzen. As early as the 1850s, Tolstoy had been deeply impressed by Herzen, whom he regarded as a ‘deep and brilliant thinker.’ The admiration was mutual; Herzen was one of the first to recognise Tolstoy’s burgeoning talent, and their correspondence had been ongoing for some years.

Photo: Afisha.London/Midjourney

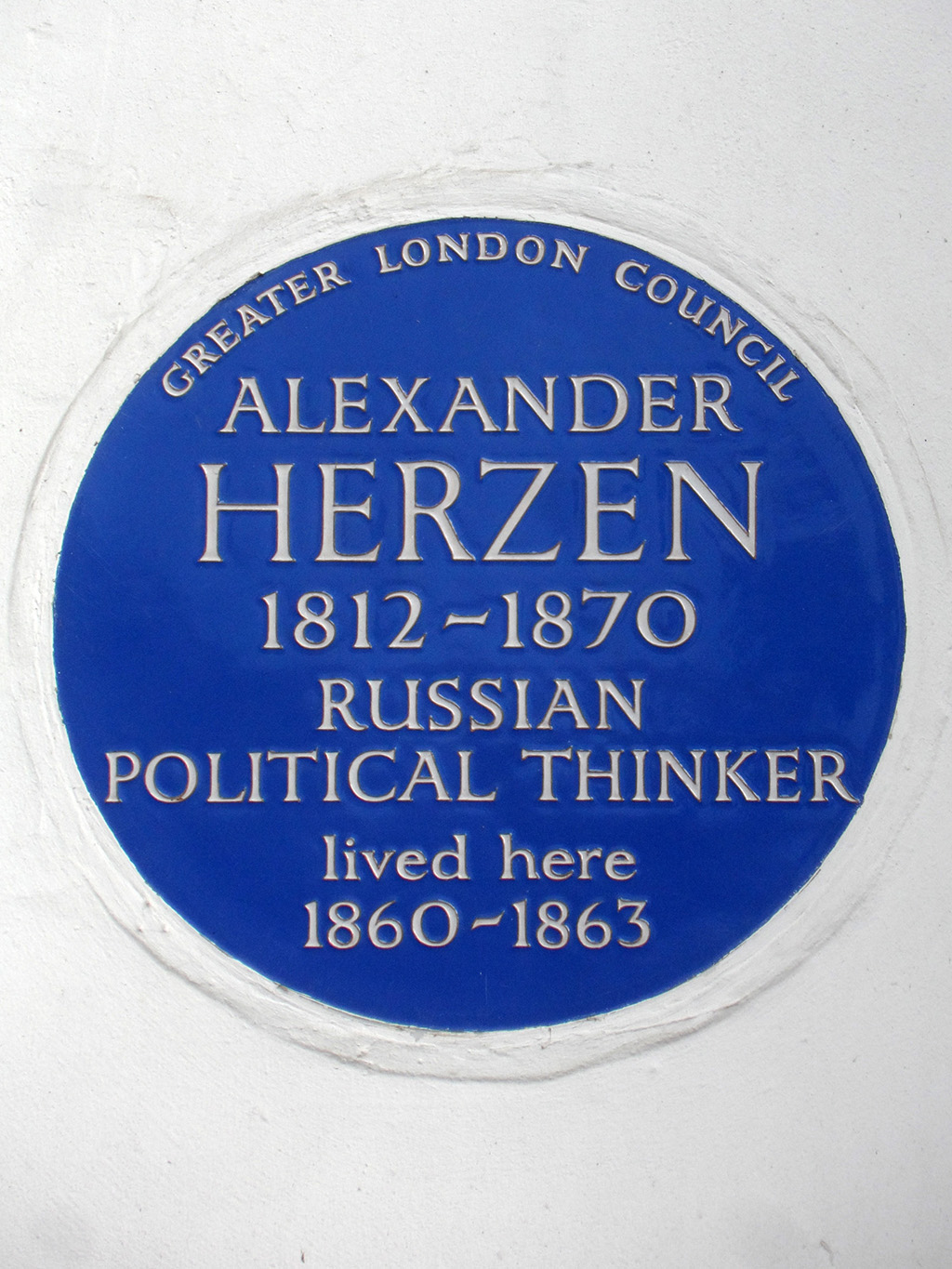

Interestingly, in 1862, the correspondence between Tolstoy and Herzen led to a search being conducted at Yasnaya Polyana. Herzen’s revolutionary works were prohibited in Russia at the time, making any association with him suspect. By the 1860s, Herzen had already established himself as a luminary within the Russian émigré community in London. His Free Russian Press published works that were censored in Russia, and his residence at 1 Orsette Terrace in Westminster became a sanctuary for ‘prodigal sons’ from various homelands. Today, a blue plaque adorns the façade of Herzen’s former residence in honour of the publicist. Interestingly, in 2019, the property was listed for sale at a price of €1.7 million.

Read also: Charles Dickens Museum: a journey into the heart of Victorian London

- Herzen House on 1 Orsett Terrace. Photo: Spudgun67, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

- Memorial plaque on the Herzen House. Photo: Spudgun67, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Tolstoy was a frequent visitor to Herzen’s residence, often engaging in intense discussions with both Herzen and Turgenev on pressing social issues. The policies of Nicholas I in 1840s Russia, set against the backdrop of the European bourgeois revolutions, sparked particularly fervent debate. Present at one of these meetings was Herzen’s 16-year-old daughter, Natasha.

She found herself disenchanted with her literary idol; the author of ‘Childhood’ appeared to her as ‘a mere dandy, a man dressed in the latest fashion,’ who animatedly discussed with Herzen the cockfights and illicit boxing matches he had witnessed in London. Adorned in the attire of a London dandy, Tolstoy scarcely resembled a philosopher, let alone the image of ‘Tolstoy the Wise Man,’ to which many have been accustomed since their youth.

Photo: Afisha.London/Midjourney

It’s worth noting that Tolstoy’s visit to London coincided with the height of the Victorian era. The city was in the midst of dramatic transformation: sewerage systems were being constructed, the Underground was being laid, and horse-drawn carriages navigated the narrow central streets while pedestrians bustled along tight pavements. Amidst these changes, Tolstoy seemed largely unperturbed by any inconveniences, focusing instead on his primary mission as ‘a gentleman from Russia interested in public education.’ Armed with a letter of recommendation from Oxford Professor Matthew Arnold, he engaged with educators from various schools. His experiences would later inspire him to establish his own school at Yasnaya Polyana, modelled after The Octagon School in London. Today, the original building of The Octagon School still stands as a private residence, situated near Fulham Broadway station.

Tolstoy was a frequent visitor to what is now known as the Victoria and Albert Museum, then called the South Kensington Museum. While the museum has undergone significant changes over the years, the building in which Tolstoy studied around 49 books remains intact. Turning to the subject of Victorian London’s social institutions, Tolstoy took particular interest in the gentlemen’s clubs he frequented. As a temporary member of the Athenaeum—the venerable literary club located on the illustrious Pall Mall—he attended a lecture by the English literary icon Charles Dickens, whom he had long aspired to meet. Tolstoy was deeply impressed by Dickens’ eloquence and imposing presence. However, his enthusiasm waned during a visit to the English Parliament, where he found Lord Palmerston’s three-hour oration to be decidedly uninspiring.

Photo: Afisha.London/Midjourney

In March 1861, Tolstoy bid farewell to London and never set foot in Europe again. However, an incident in 1872 at Yasnaya Polyana almost led him to contemplate emigration to England. A bull he owned had fatally injured a shepherd, leading to an investigation that put Tolstoy under considerable legal scrutiny. Fearing the potential loss of his freedom, the count, by then a renowned figure for his novel ‘War and Peace,’ seriously considered liquidating his assets and relocating to England. Ultimately, the situation culminated in a substantial fine for Tolstoy, who remained at Yasnaya Polyana for the majority of his remaining years. It was there that he completed ‘Anna Karenina’ by 1877.

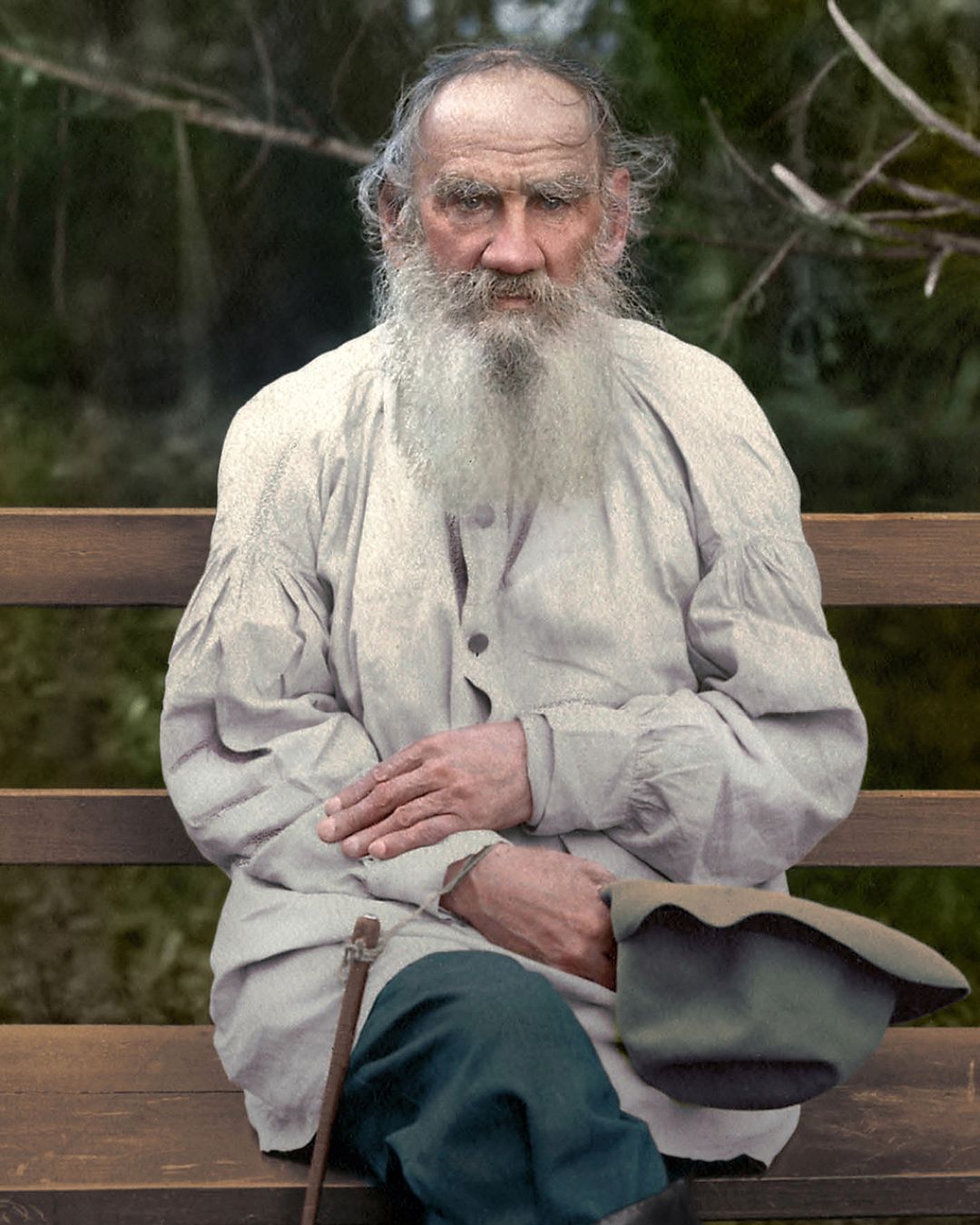

- Leo Tolstoy. Colour photo: Klimbim

- Lev Nikolaevich and Sophia Andreevna Tolstoy. Colour photo: Klimbim

Tolstoy in the perception of the British

In the 1870s and 1880s, Tolstoy’s works reached British shores primarily through French or American translations. Yet even in these secondary versions, they had a profound impact on the British literary landscape. The eminent critic Matthew Arnold, whom we’ve encountered earlier, opined in his 1887 article ‘Count Leo Tolstoy’ that Russian literature was coming into its own precisely as the Victorian novel had lost its lustre and French literature was becoming increasingly unpalatable due to its social provocations and extremes.

Read more: The legendary Russian children’s poet Korney Chukovsky in London

Arnold found ‘Anna Karenina’ beguiling, although he categorised it more as a chronicle of life than as a crafted work of art. Distinguished publicist George Perris, in his work ‘Leo Tolstoy the Grand Mujik: A Study in Personal Evolution,’ described Tolstoy as epitomising wisdom in the eyes of the British public. However, Tolstoy was not without his critics, some of whom questioned the vitality of his writing, citing it as a shortcoming related to form and the lack of a clear structural focus.

During the Second World War, Tolstoy’s works experienced a resurgence in popularity in Britain, buoyed by the enduring themes of life depicted in his novels. Tatyana Krasavchenko, a Doctor of Philology, mentions in her article ‘Leo Tolstoy in the Space of British Culture’ that in 1943, a dramatised adaptation of ‘War and Peace’ was broadcast on BBC Radio. Spanning eight instalments and airing each Sunday, this production boasted a star-studded cast. Krasavchenko attributes the renewed British interest in Tolstoy to the geopolitical landscape of the time—Russia, in 1943, was Britain’s principal ally, bearing the brunt of Hitler’s assault. The absence of a British epic novel equivalent to ‘War and Peace’ also contributed to its appeal. Fast-forward to 2016, and the BBC launched a mini-series adaptation of ‘War and Peace,’ with filming taking place in iconic locations such as Palace Square and Yusupov Palace in St. Petersburg, as well as Gatchina. Likewise, scenes from the adaptation of ‘Anna Karenina,’ starring Sophie Marceau, were also filmed in St. Petersburg, an aspect we explored in our previous article, which also discussed popular film adaptations of the novel, including the British version featuring Keira Knightley.

Yasnaya Polyana, where the writer lived most of his life. Photo: © A.Savin, FAL, via Wikimedia Commons

Returning to Yasnaya Polyana, it’s worth noting that when Tolstoy passed away on 20 November 1910, he was laid to rest in the leafy park alley of his family estate. His funeral drew several thousand mourners, despite the radical transformation in his beliefs over the last three decades of his life. This shift led him to renounce all worldly possessions, including the copyrights to his own works, causing considerable uproar among his family, particularly his wife Sophia. The tumultuous final year of Tolstoy’s life was captured in the 2009 international film ‘The Last Station,’ co-produced by Andrei Konchalovsky. The film featured Helen Mirren, an actress of Russian descent, in the role of Sophia, Tolstoy’s wife.

Cover photo Afisha.London/Midjourney

Read more:

Composer Pyotr Tchaikovsky in London: impressions, recognition and success

How Diaghilev’s “Saisons Russes” influenced the European art world of the 20th century

Bakst, Benois and Dobuzhinsky: How an Extensive Collection of Russian Art Ended Up in Oxford

SUBSCRIBE

Receive our digest once a week with quality Russian events and articles