Winston Churchill: descendant of a pirate, impressionist and husband to the perfect wife

Winston Churchill remains a figure of fascination and division, stirring either deep admiration or intense criticism. Twice serving as Prime Minister, he guided Britain through the crucible of the Second World War, leaving an indelible mark on history. Beyond his political achievements, Churchill’s extraordinary life was coloured by a flair for the unconventional. On the anniversary of his birth, Afisha.London art-magazine reflects on the multifaceted legacy of a man who reported from war zones, escaped captivity, penned articles, won the Nobel Prize for Literature, painted landscapes, lived outrageously, and married one of the wisest women of his era.

A Heritage Rooted in Nobility and Adventure

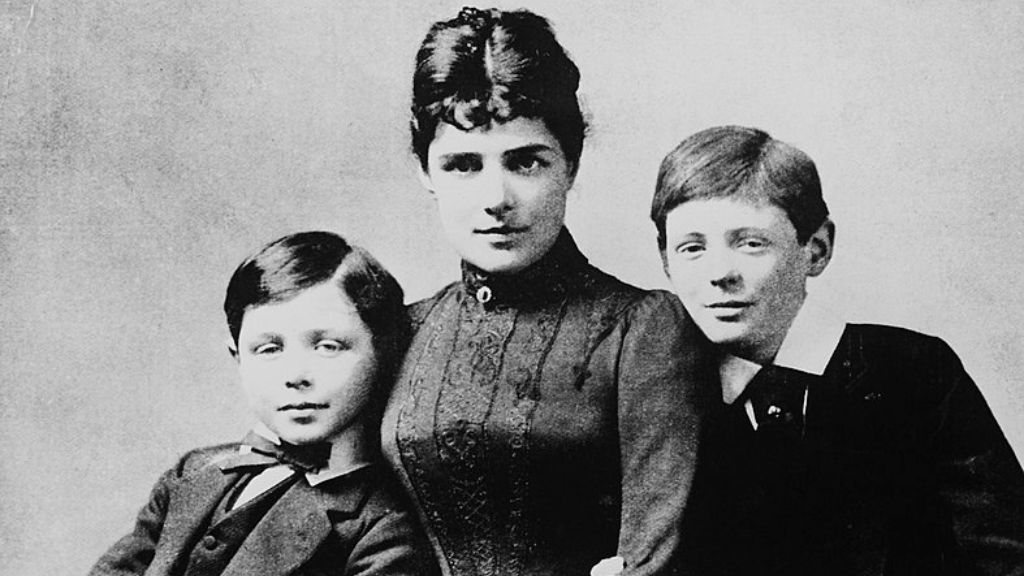

Churchill’s remarkable journey began with an equally remarkable birth. On 30 November 1874, amidst a lavish ball at Blenheim Palace, the ancestral home of the Spencer-Churchill family in Oxfordshire, the red-haired infant arrived in dramatic fashion. His spirited mother, Jennie, danced so enthusiastically in the late stages of her pregnancy that she gave birth in the cloakroom, atop a heap of shawls and furs.

A doctor was summoned, but Churchill had already announced his presence with a resounding cry. Such an unconventional start befitted his illustrious lineage. On his American mother’s side, he was distantly related to President Roosevelt, while his British father, Lord Randolph Churchill, descended from the aristocratic Dukes of Marlborough. His bloodline even traced back to the infamous “legal pirate” Sir Francis Drake, whose exploits we’ve detailed in our exploration of England’s maritime adventurers.

Early Years in London and the Influence of Miss Everest

At the age of five, young Winston moved to London with his family, settling in a grand residence at 29 St James’s Place. Today, the house bears a commemorative plaque marking Churchill’s three formative years there, during which he was cared for by his devoted nanny, Miss Everest. Serving as a surrogate mother, Miss Everest’s influence on Churchill was profound. Her portrait would later hang in his study for life, a tribute to her steadfast care amidst his parents’ distractions — his father absorbed in politics and illness, and his mother immersed in the social whirl.

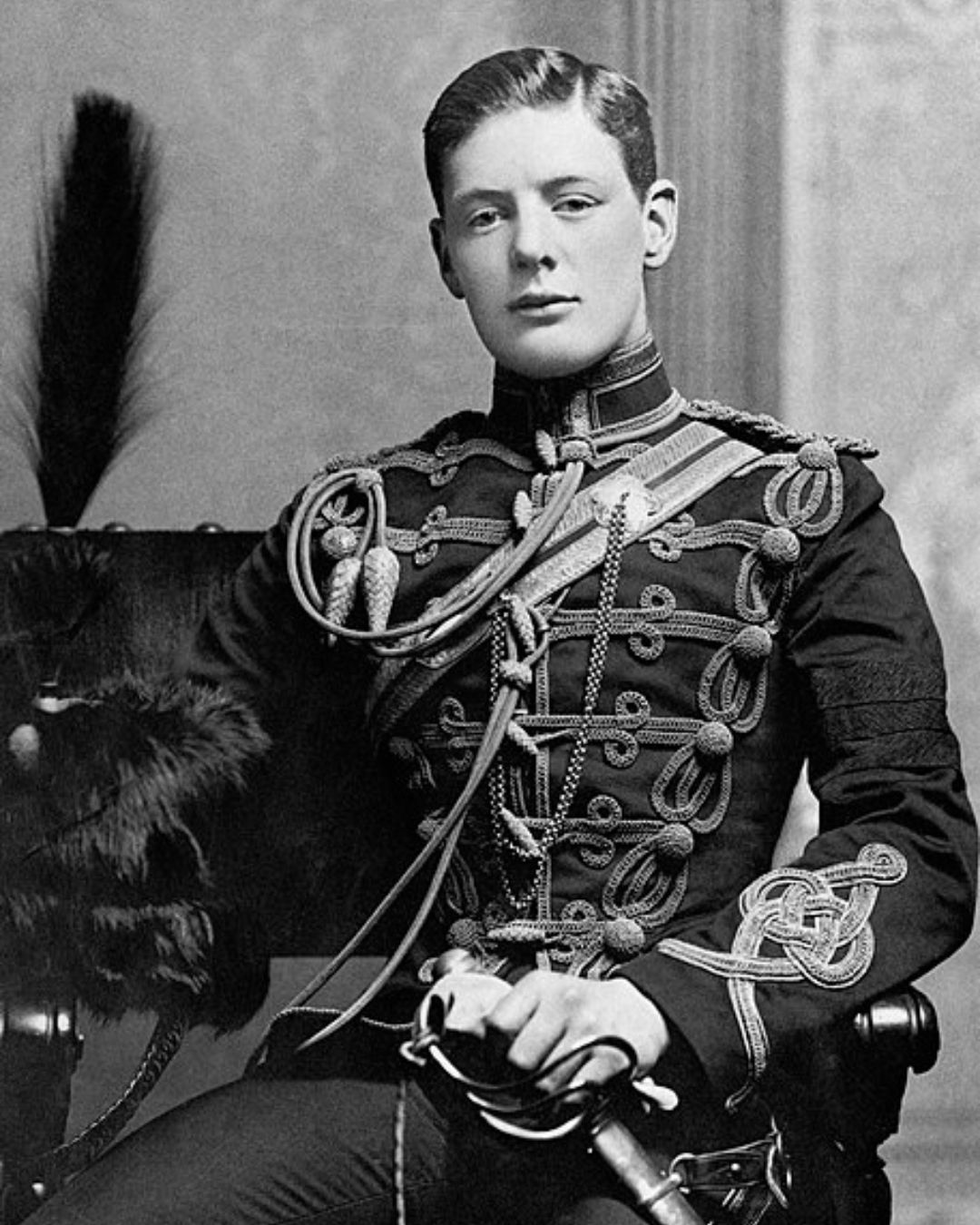

Education was another matter. Churchill was sent to Harrow, a prestigious school where corporal punishment was commonplace. Academically underwhelming, he was frequently at the receiving end of discipline. However, Miss Everest recognised a resilient spirit in young Winston and suggested that military service might channel his tenacity. This advice proved prescient. Churchill enrolled at the Royal Military Academy, Sandhurst, excelling in his studies and graduating as one of the top cadets. He was subsequently commissioned into the elite 4th Hussars, setting the stage for a life of action and adventure.

This tapestry of noble heritage, early struggles, and indomitable resolve was the foundation upon which Churchill would build a legacy that continues to resonate, inspiring admiration and debate in equal measure.

Read also: The great and terrible English pirates: the romanticised image of sea wolves

Churchill’s First Adventures: From Cuba to Literary Fame

In 1895, a young and ambitious Winston Churchill sought out his first mission — quelling an uprising in Cuba. Later posted to India with his regiment, Churchill found himself in an officer’s bungalow complete with a garden but devoid of meaningful occupation. Polo and leisurely reading became his primary pursuits. To his surprise, the disdain for books he had harboured since school gave way to a newfound passion for literature. Immersing himself in classical works, he was inspired not only to read but to write, penning essays, short stories, and articles that quickly gained recognition.

Churchill soon realised he could marry his two great passions — warfare and writing.

Jenny with her two sons, John and Winston (on the right), 1889. Photo: See page for author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

A War Correspondent in Global Hotspots

As a military correspondent, Churchill ventured to conflict zones in Afghanistan, Egypt, and South Africa, delivering vivid, firsthand accounts of battles and skirmishes. His dispatches were eagerly published by Britain’s leading newspapers, earning him fees that dwarfed his officer’s salary. For example, his reports for The Morning Post — a precursor to The Daily Telegraph — commanded £250 per month, a princely sum at the time. Churchill’s prolific output extended across multiple publications, solidifying his reputation as a skilled chronicler of war.

One of his most dramatic and celebrated stories unfolded during the Second Boer War in 1899. Captured by Boer forces, Churchill spent a month in captivity before orchestrating a daring escape that captured the imagination of the British public. His account of the ordeal, rich in tension and adventure, became a national sensation, transforming Churchill’s escape into a best-selling narrative. Britain was enthralled by this audacious officer who turned every challenge into a triumph, laying the groundwork for his enduring legacy.

Read also: Virginia Woolf and her fascination with Russian literature

Wedded Bliss and the Secrets of a Churchillian Marriage

At 25, disillusioned by the romanticised notion of military life, Winston Churchill resigned his commission to pursue a new battlefield: politics. Discovering a natural talent for oratory, he delivered speeches that were concise, passionate, and often laced with humour, winning over audiences across the social spectrum. In 1900, he entered Parliament as a Conservative MP but briefly stepped away from politics to pen a two-volume biography of his ill-fated father, Lord Randolph Churchill. With his characteristic flair, Churchill managed to present his father as a model politician and exemplary family man.

The Awkward Suitor Finds the Perfect Match

Despite his many gifts, Churchill was notoriously inept when it came to matters of the heart. By the age of 30, the charismatic politician had yet to marry, a surprising state of affairs for a man of his stature. His shyness often undermined his efforts, leading to missed opportunities. Such was the case in 1904, when Churchill first encountered Clementine Hozier, a striking beauty from a noble but impoverished family, at a ball. Overwhelmed by her grace and charm, Churchill was rendered speechless, failing even to ask her for a dance.

Their next meeting, however, was a turning point. Four years later, at a formal dinner, Churchill seized his chance, courting Clementine with a clumsy yet earnest determination. Recognising the depth and sincerity of his intentions, she accepted his proposal in 1908. The engagement unfolded in the most romantic of settings: caught in a rainstorm at Blenheim Palace, Churchill’s ancestral home, the couple sought shelter in the Temple of Diana. There, amidst the storied grounds, Winston asked Clementine to be his wife. It was a union that would last 57 years, until Churchill’s death, with Clementine standing steadfastly by his side as his unwavering partner.

“In Blenheim, I made two important decisions: to be born and to marry,” Churchill later reflected in his autobiography, “and I am thoroughly pleased with both.”

Their marriage became a cornerstone of Churchill’s life, with Clementine’s wisdom and support balancing his tempestuous nature. While Churchill was larger-than-life in the public eye, it was Clementine who provided the quiet strength and guidance that ensured his triumphs were not just his own but shared.

Read as well: Flappers — emancipated women of the 20s in the West and in Russia

- Lieutenant Winston Churchill of the 4th Queen’s Own Hussars in 1895. Photo: See page for author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

- Portrait of Winston Churchill, 1900. Photo: See page for author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Building a Life Together: The Enduring Partnership of Winston and Clementine Churchill

In 1909, the Churchills moved into a grand townhouse at 33 Eccleston Square, located in the heart of London. Today, the home bears a blue plaque commemorating their residence. It was here that their first two children, Diana and Randolph, were born. By 1911, following Winston’s appointment as First Lord of the Admiralty, the family relocated to an apartment in Admiralty House, befitting his elevated role.

At the time, sceptics doubted the longevity of the Churchill marriage, convinced the couple was too different to last even six months. Winston’s impulsive nature, boundless confidence, and penchant for unhealthy habits contrasted sharply with Clementine’s calm demeanour, steely composure, and incisive intellect. Yet it was precisely these differences that made their partnership resilient. Clementine, with her wisdom and patience, grounded Winston, while he relied on her sharp mind — even in political matters.

If you are fond of cigars like Churchill, we recommend that you take a look at special temperature-controlled storage boxes herе and here.

A Union of Equals

Clementine’s influence extended beyond their household. Her sympathies towards communism, for instance, subtly shaped Winston’s decisions during the Second World War, contributing to the formation of the crucial alliance between Britain and the Soviet Union against fascism. During long periods of separation, the couple exchanged heartfelt letters, filled with affection and mutual support. In 2008, these correspondences were published by the Churchill Archive Centre to mark the centenary of their marriage, offering a glimpse into their unwavering bond.

Clementine’s guiding principle in their marriage was simple yet profound: she accepted Winston as he was. Her oft-quoted advice to other wives was, “Never make husbands do this!” — “this” being the futile attempt to mould one’s partner or force agreement on every matter.

- Clementine, 1915. Photo: Initial photograph : unattributed, AI image processing : Madelgarius, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

- Churchill and his wife on board a naval auxiliary patrol vessel during a visit to the London docks, 25 September 1940. Photo: William George Horton, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Triumphs and Tragedies

The Churchills went on to have three more children: Sarah, Marigold, and Mary. Tragically, Marigold, born in 1918 shortly after the end of the First World War, did not live to see her third birthday. Sent with her nanny to the Kent coast for fresh air, she caught a severe cold that quickly worsened. Despite the parents’ frantic efforts, including summoning a leading London physician, the little girl could not be saved. The loss devastated both Clementine and Winston, who blamed themselves for her death.

Yet, their marriage endured this heartbreak. In 1922, Clementine gave birth to their fifth child, Mary, and the family found a renewed sense of stability. Among the Churchill children, it was Mary who most fulfilled her parents’ expectations. During the Second World War, she volunteered for service and often accompanied her father on overseas trips. Later, she married successfully, raised five children, and became a writer herself, carrying on her parents’ legacy in her own way.

Through trials and triumphs, the Churchill marriage stood as a testament to love, resilience, and mutual respect, forming the bedrock of Winston’s life and career. Clementine’s wisdom and unwavering support allowed Winston to thrive, while their shared joys and sorrows forged an unbreakable bond that weathered even the harshest storms.

Read also: Felix Yusupov and Princess Irina of Russia: love, riches and emigration

- ‘Two Girls Seated, Diana and Sarah Churchill’ by Charles Sims. Photo: Charles Sims, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

- Churchill’s daughter Mary, 1965. Photo Ron Kroon / Anefo, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Chartwell: A Retreat for a Statesman, an Artist’s Haven, and a Literary Laureate

In 1921, the Churchills moved to 2 Sussex Square, a residence north of Hyde Park that, like many of their previous homes, is now commemorated with a blue plaque. However, it was in September 1922 that Winston Churchill acquired a property that would become synonymous with his name and his creative pursuits: Chartwell, a 16th-century manor house nestled in the rolling countryside of Kent.

Initially, Chartwell failed to impress Churchill. The previous owner had transformed the manor into a staid Victorian house that lacked the charm Churchill sought. Yet the idyllic rural setting, long a dream of his, ultimately won him over. To reshape the property into a stately retreat befitting his vision, Churchill hired the celebrated architect, Philip Tilden.

Read as well: Modernist Legend Henry Moore and His Muse, Irina Radetzky

A house in Chartwell, Kent. Deben Dave at English Wikipedia, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

A Country Home Reimagined

What began as a straightforward renovation quickly spiralled into an architectural saga. Over two years, the original budget of £7,000 ballooned to £18,500, straining relations between Churchill and Tilden to the point where they nearly stopped speaking. Despite the tensions, the result was a resplendent estate that exceeded all expectations. Chartwell boasted five drawing rooms, 19 bedrooms, and eight bathrooms. Surrounding the house were 77 acres of lush gardens, including a rose garden meticulously curated by Clementine, a goldfish pond, and two cottages that Churchill later added. A swimming pool completed the picturesque scene.

Chartwell was more than just a home; it was a sanctuary for Churchill’s myriad interests. He turned one of the rooms into a studio, where he found solace in painting, a hobby that became a lifelong passion. Inspired by the serene landscapes of Kent, Churchill created over 500 works of art, many of which remain on display at Chartwell today.

A Nobel Laureate and a Place of Reflection

It was during his years at Chartwell that Churchill also cemented his literary legacy. Writing prolifically, he produced numerous books, essays, and speeches, earning him the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1953. The prize recognised not only his historical writings and eloquent oratory but also his ability to inspire through the written word. Chartwell became a space where the complexities of Churchill’s life — politician, artist, writer, and family man — harmoniously converged. It was a place of tranquillity and productivity, where he could escape the pressures of public life and channel his boundless energy into his passions. For over four decades, Chartwell remained Churchill’s cherished retreat, a home that reflected both his ambitions and his humanity. Today, it stands as a testament to his enduring legacy, inviting visitors to walk the same halls and gardens that nurtured one of Britain’s most iconic figures.

You might also like: Five British artists, who had a close connection to Russia

‘The Goldfish Pool at Chartwell’, 1932 Photo: © Churchill Heritage Ltd

Chartwell: A Symbol of Leadership, Art, and Resilience

Chartwell, one of Britain’s most iconic residences, became a hub of wartime leadership and diplomacy during the Second World War. From this country retreat, Winston Churchill directed military strategy, hosted world leaders, and entertained influential figures. In 1938, the Soviet ambassador Ivan Maisky visited Chartwell and was struck by its picturesque views of rolling hills, impressive wine cellars, and Churchill’s art studio, which showcased his paintings.

Churchill’s talent for painting emerged during the First World War in 1915, as he sketched scenes from the front lines. Throughout his life, painting provided solace during his bouts of depression, often triggered by political setbacks. Wherever he travelled, Churchill carried a box of paints and brushes, and in every home, he set up a studio. Seated at his easel, cigar in hand, he found peace in the act of creation, though he doubted his abilities as an artist. Despite his modesty, Churchill completed around 500 paintings, many of which he gifted to friends and family.

His final painting, The Goldfish Pond at Chartwell, was completed in 1962 and presented to his bodyguard. In 2017, the artwork was auctioned by Sotheby’s, fetching £357,000 — far surpassing its initial estimate of £80,000. An earlier version of the same subject, painted in 1932, sold for an astonishing £1.8 million, cementing Churchill’s legacy as a remarkable artist.

A Life of Unrelenting Productivity

Churchill’s work ethic was extraordinary. In 1953, he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature, besting none other than Ernest Hemingway, who would win the following year. Churchill was recognised for his masterful historical works, speeches, and literary contributions. Despite his infamous vices — chain-smoking cigars, indulgent eating habits, and a love for alcohol — Churchill defied expectations and lived to the age of 90. His longevity outlasted even the pallbearers originally chosen for his state funeral, which had been meticulously planned years in advance by Queen Elizabeth II and detailed in a 400-page document. When Churchill passed away on 24 January 1965, his funeral was a spectacle of royal proportions. Over 100,000 people lined the streets to bid farewell as Britain honoured him with a state ceremony befitting a monarch. He was laid to rest in his birthplace, at the graveyard of St Martin’s Church in Bladon.

The Legacy of “Never Give In”

For Clementine Churchill, who had always placed her husband above all else, coping with his loss might have seemed insurmountable. Yet she found strength in his own words—his iconic message delivered to Harrow School students during the dark days of 1941: “Never, never, never, never give in. Never yield in great things or small, large or petty.” This speech, given in the midst of Britain’s struggle against Nazi Germany, remains a source of inspiration for those facing adversity. It is a reflection of Churchill’s indomitable spirit, which continues to guide and encourage countless individuals to persevere, as he himself did throughout his extraordinary life.

You can learn more about Winston Churchill’s life by visiting the Bunker — office where he worked during the war. Book here

Irina Lazio/Margarita Bagrova

Cover photo: Midjourney / Afisha.London

Read also:

Nicholas II and George V: A History of Friendship and Duty

The history of crystal: how an English invention thrived in Russia

The love and hate story of artist Pablo Picasso and Ballets Russes dancer Olga Khokhlova

SUBSCRIBE

Receive our digest once a week with quality Russian events and articles