Five British artists, who had a close connection to Russia

Russian-British relations greatly flourished during Catherine the Great’s reign, especially in terms of artistic exchange. The empress actively invited British artists to Russia and bought their works for the State Hermitage’s collection. Later this tradition had been continued by Alexander I, who invited an English portraitist George Dawe to paint for the Military Gallery of the Winter Palace. Afisha.London magazine embarks on an historical journey to tell the stories of five British artists, whose work was closely associated with Russia.

The starting point for the development of the modern Russian-British relations was Peter the Great’s visit to Great Britain in 1698. However, back then the tsar did not express any interest in British art and culture. Interactions between the two countries became more active and diverse only with the arrival of Catherine the Great, reaching a particular intensity in the 1770-80s.

The empress once wrote: “I look at the English nation as the one whose union is the most natural and useful for Russia”. She showed an interest in British art, theatre, literature, philosophy and even park design. Catherine the Great was one of the first foreign monarchs to develop such a fondness for British art that elevated to the level of public collecting. By 1794 there already were about twenty English school paintings in the Imperial collection. At some point an art collection that belonged to the first British prime minister Robert Walpole, which consisted of 198 paintings, was also acquired for the State Hermitage.

This interest in British culture was shared by some of the wealthiest Russian families of the time. For example, Prince Vorontsov formed his private collection during his stay in London as a diplomat, while Prince Potemkin, Сatherine the Great’s favourite, had paintings by Joshua Reynolds and Richard Brompton as well as numerous engravings and prints with views of England, Scotland and Wales.

Joshua Reynolds

Joshua Reynolds was one of the greatest British painters of the eighteenth century. The artist studied ancient art as well as Italian Renaissance, while the works of Rubens and Rembrandt also had a great influence on his style. Thanks to his ability to express the individuality of those he painted, Reynolds was a very popular portraitist, however, he never received commissions from the royal court. Even though he fervently considered historical painting to be the noblest genre, he paid the bills solely due to his work as a portraitist (he completed up to 150 portraits a year).

- Joshua Reynolds “Cupid Untying the Zone of Venus”, Tate Britain (copies at Sir John Soane’s Museum and Hermitage Museum). Photo: Joshua Reynolds, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

- Joshua Reynolds “Infant Hercules Strangling Serpents”, Hermitage Museum. Photo: Joshua Reynolds, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The artist became the first president of the Royal Academy of Arts, which was founded in 1768. He shared his views on art in his addresses to the students before the opening of the Academy each year, on the basis of which a collection of fifteen “Speeches” was compiled. It was published in several European languages, including Russian, with the translation decreed by Catherine the Great. In 1785 Reynolds received an historical painting commission from the Russian empress. By that time the artist’s eyesight had significantly deteriorated, which made painting much harder for him, however, Reynolds simply could not refuse the empress. He presented her with “Infant Hercules Strangling Serpents”, a painting, which symbolised the growing power of Russia (it is “… an allusion to the enormous difficulties that it [Russia] had to face,” – the author himself wrote).

- Joshua Reynolds “Continence of Scipio”, Hermitage Museum. Photo: Joshua Reynolds, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

- Joshua Reynolds “Portrait of Sir William Hamilton”, National Portrait Gallery. Photo: Joshua Reynolds, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Prince Potemkin also had paintings by Reynolds in his collection. The artist was commissioned to paint for the prince via a British diplomat Lord Carysfort the very same year that he received a commission from Catherine the Great. This is how Reynolds created “Continence of Scipio”, in which one can find a hint of the military prowess of Prince Potemkin, who led the Russian army in the Russian-Turkish campaigns. Also, Reynolds painted “Cupid Untying the Zone of Venus” for the aforementioned Lord Carysfort, who commissioned the artist to make a copy, which he then gave to Prince Potemkin. At the moment there are three versions of this painting: the original, created in 1784, is in Tate Britain, while the two copies are in the Sir John Soane’s Museum and in the Hermitage.

Where to find:

- National Portrait Gallery, London

- Tate Britain, London

- Royal Collection Trust, UK

- Sir John Soane’s Museum, London

- Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg

George Dawe

George Dawe received his primary art education from his father, a mezzotint engraver and cartoonist Philip Dawe. He then studied at the Royal Academy of Arts in London, from which he graduated with a gold medal, and later became an academician. Dawe was invited to Saint Petersburg to paint portraits for the Military Gallery of the Winter Palace. In 1819 the artist arrived in Russia, and the next ten years of his life were associated with the Russian capital. Alexander I’s choice fell on Dawe for a reason: the artist was famous for his quick work and ability to complete a painting in only 2-3 sessions.

- George Dawe “Portrait of General Pyotr Bagration”, Hermitage Museum. Photo: George Dawe, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

- George Dawe “Portrait of Mikhail Kutuzov”, Hermitage Museum. Photo: George Dawe, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Dawe worked on the portraits for the Military Gallery together with his two students, Polyakov and Golike; however, even with their assistance the process was rather intense. Even after the gallery was officially opened in December 1826, Dawe continued working on the portraits until the very last days of his stay in Russia. The artist painted a portrait of one of the most famous Russian military commanders Mikhail Kutuzov 16 years after the death of the field marshal. Kutuzov did not like posing for ceremonial portraits, which is why Dawe had to “construct” the commander’s figure himself, while as the model of the face he probably had the portrait by Roman Volkov – the last depiction of Kutuzov completed while the marshal was alive.

- George Dawe “Alexander I, Emperor of Russia”, Royal Collection Trust. Photo: George Dawe, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

- George Dawe “Portrait of Fieldmarshal Mikhail B. Barclay de Tolly”, Hermitage Museum. Photo: George Dawe, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The British artist also accepted private commissions, thanks to which he acquired a huge fortune. Getting a George Dawe portrait was considered prestigious and fashionable. For his work Dawe asked for 800-1000 roubles, an outstanding amount at the time, and this price was several times higher than the average requests of Russian artists.

Read more: Leo Tolstoy in London: shaping the british literary landscape

The Committee of the Society for the Encouragement of Artists even wrote a letter of complaint to Alexander I, in which they called the artist a “commercialist”. Russian writers, however, were not as critical as artists. For example, a Russian writer, publisher and editor Pavel Svinin wrote about Dawe in a journal “Otechestvennye Zapiski” (Annals of the Fatherland), expressing his fascination by the British artist’s technique. Moreover, Alexander Pushkin mentioned the Briton in his poem “To Kiprensky” and in 1828 even wrote an entire dedication to the artist entitled “To Dawe, Esqr”.

Where to find:

- National Portrait Gallery, London

- Tate Britain, London

- Royal Collection Trust, UK

- Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg

- Saint Michael’s Castle, Saint Petersburg

Richard Brompton

Travelling through Italy and getting to know the outstanding works of antiquity and the Renaissance was an obligatory stage in the education of every young British artist and sculptor. It was in that country that Richard Brompton was taken under the wing by a major German painter Anton Raphael Mengs. When Brompton returned home, he took an active part in the exhibitions of the Society of Artists of Great Britain and was elected its president. He also worked as a court portraitist for King George III. Despite his success in Great Britain, the artist lived beyond his means and was put on trial. It is believed that Catherine the Great rescued Brompton from a debt prison by inviting him to Russia. The artist retained his gratitude until the end of his life, calling his children after the empress and her grandson, Grand Duke Alexander Pavlovich.

- Richard Brompton “Portrait of Alexandra Branitskaya”, Vorontsov Palace. Photo: Richard Brompton, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

- Richard Brompton “Portrait of Admiral Sir Charles Saunders”, National Maritime Museum. Photo: Richard Brompton, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Catherine the Great was actively involved in the upbringing of her grandchildren, the Grand Dukes Alexander Pavlovich and Konstantin Pavlovich, and pinned great hopes on them. It is quite likely that completing their portraits was the main task of the invited artist. In 1781 Brompton finished their portrait, which has become a model for depicting royal heirs at a young age. The painting portrays the Grand Duke Alexander, who is cutting the Gordian knot, and his younger brother, Constantine, who in his right hand is holding a banner crowned with a labarum – a victorious cross, which is a symbol of the victory of Christianity.

Read more: Composer Pyotr Tchaikovsky in London: impressions, recognition and success

“Brompton is an artist, who has settled here and has a great talent; he painted my two grandchildren. This painting in my gallery does not look any worse than van Dyck’s paintings,” – wrote Catherine the Great. This comparison was made for a reason, as in his work Brompton took inspiration from van Dyck’s compositions. Moreover, back in England, the artist made an attempt at restoring one of the paintings by the great Flemish artist.

- Richard Brompton “Portrait of Catherine the Great”, Hermitage Museum. Photo: Richard Brompton, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

- Richard Brompton “Portrait of Grand Dukes Alexander Pavlovich and Constantin Pavlovich”, Hermitage Museum. Photo: Richard Brompton, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

One of Brompton’s most significant works is a portrait of Catherine the Great. In this portrait the empress is depicted at the age of 53 wearing an ermine mantle, a large chain and a star of the Order of St. Andrew, a star and ribbon of the Order of St. George of the first degree and a small imperial crown. This was the time in Catherine the Great’s reign, when artists began depicting her smiling.

Where to find:

- The British Museum, London

- National Portrait Gallery, London

- Royal Collection Trust, UK

- National Maritime Museum, London

- Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg

- Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

Christina Robertson

It is impossible to say for sure on whose recommendation Christina Robertson, who had already earned a reputation as a fashionable miniaturist in England and Scotland, came to Russia. The name Robertson was first mentioned in the Russian press in 1839, when she exhibited her works at the Academy of Arts. “The best portrait of all exhibited at the Academy, however, is a portrait of a lady in a white satin dress playing the organ. It could be safely placed next to a Rembrandt, and it would not have lost much value from being next to such a dangerous neighbour,” – noted one critic.

- Christina Robertson “Portrait of Empress Alexandra Fyodorovna”, Hermitage Museum. Photo: Christina Robertson, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

- Christina Robertson “Portrait of Zinaida I. Yusupova”, Hermitage Museum. Photo: Christina Robertson, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

She did not have to wait long for a commission from the royal family. In the spring of 1841 Robertson was invited to the court to paint portraits of Nicholas I and his family. For the portraits of the empress and her three daughters, presented at an Academy exhibition, the artist received the title of an honorary free associate of the Imperial Academy of Arts (before her only one woman was awarded this title – a French artist Élizabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun).

Read more: Rudolf Nureyev: an emigrant, who became a ballet legend

After her success in Russia, the artist left for London, where she continued exhibiting her works. Curiously, on the second day of her stay back in Great Britain she twisted her leg. “I will remain lame … forever. I am very sad that I will not be able to come to Petersburg to my friends,” – she wrote to the curator of engravings at the Hermitage. However, in 1847 Robertson returned to Saint Petersburg nevertheless. She was to paint portraits of the daughters-in-law of Nicholas I – Maria Alexandrovna and Alexandra Iosifovna. She was given a room in the Hermitage, a daily breakfast at 12 o’clock as well as other privileges, but despite all this, only the portrait of Maria Alexandrovna satisfied the emperor. For the rest of the canvases he ordered to be returned back to Robertson without payment.

- Christina Robertson “Children with a Parrot”, Hermitage Museum. Photo: Christina Robertson, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

- Christina Robertson “Portrait of Grand Duchess Maria Alexandrovna”, Hermitage Museum. Photo: Christina Robertson, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Many of the clients who posed for Robertson were closely associated with Great Britain. Prince Ivan Baryatinsky, who at the beginning of the nineteenth century served as the secretary of the Russian embassy in London, was married to the daughter of Lord Sherborne, and Orlov-Davydov (Ivan Baryatinsky’s son-in-law) graduated from the University of Edinburgh and was acquainted with Walter Scott. Unfortunately, the once famous and wealthy artist was forgotten during her lifetime. There are several theories as to why this happened.

Read more: How Diaghilev’s “Saisons Russes” influenced the European art world of the 20th century

Firstly, Robertson’s paintings cannot be called great works of art, they are primarily curious as a historical and artistic document. Secondly, they were mainly intended for private offices and quarters, which is why they were inaccessible to the general public. Thirdly, she died far from home in 1854 in Saint Petersburg during the peak of Crimean War, which aggravated Russian-British relations. Judging by her letters to the Grand Duchess Maria Nikolaevna, she wanted to return to her homeland but could not do this due to a lack of funds.

Where to find:

- Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg

- Russian Museum, Saint Petersburg

John Augustus Atkinson

John Augustus Atkinson moved from London to Saint Petersburg at the age of nine, and his life was closely associated with the royal court. John Walker, his uncle or stepfather (exact details are not known), was an excellent graphic artist and a master of reproductive engraving, working mainly in the mezzotint technique. Walker was invited by Catherine the Great to make engravings of the works from her collection and to elevate the Hermitage’s status in Europe. Meanwhile, young Atkinson was fascinated by Russian life with its curious, from a foreigner’s perspective, traditions. One of his early paintings depicts a beloved Russian pastime, which is popular during Maslenitsa (an Eastern Slavic holiday) – “Riding from the Hills on the Neva River”. Already at 22 he was commissioned to paint an equestrian portrait of Emperor Paul I. Despite its small size, only 71×50 cm, according to its composition it was a ceremonial portrait. However, now some of Atkinson’s portraits are only known from prints and copies made by other artists.

John Augustus Atkinson “View of Saint Petersburg”. Photo: Hermitage Museum, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

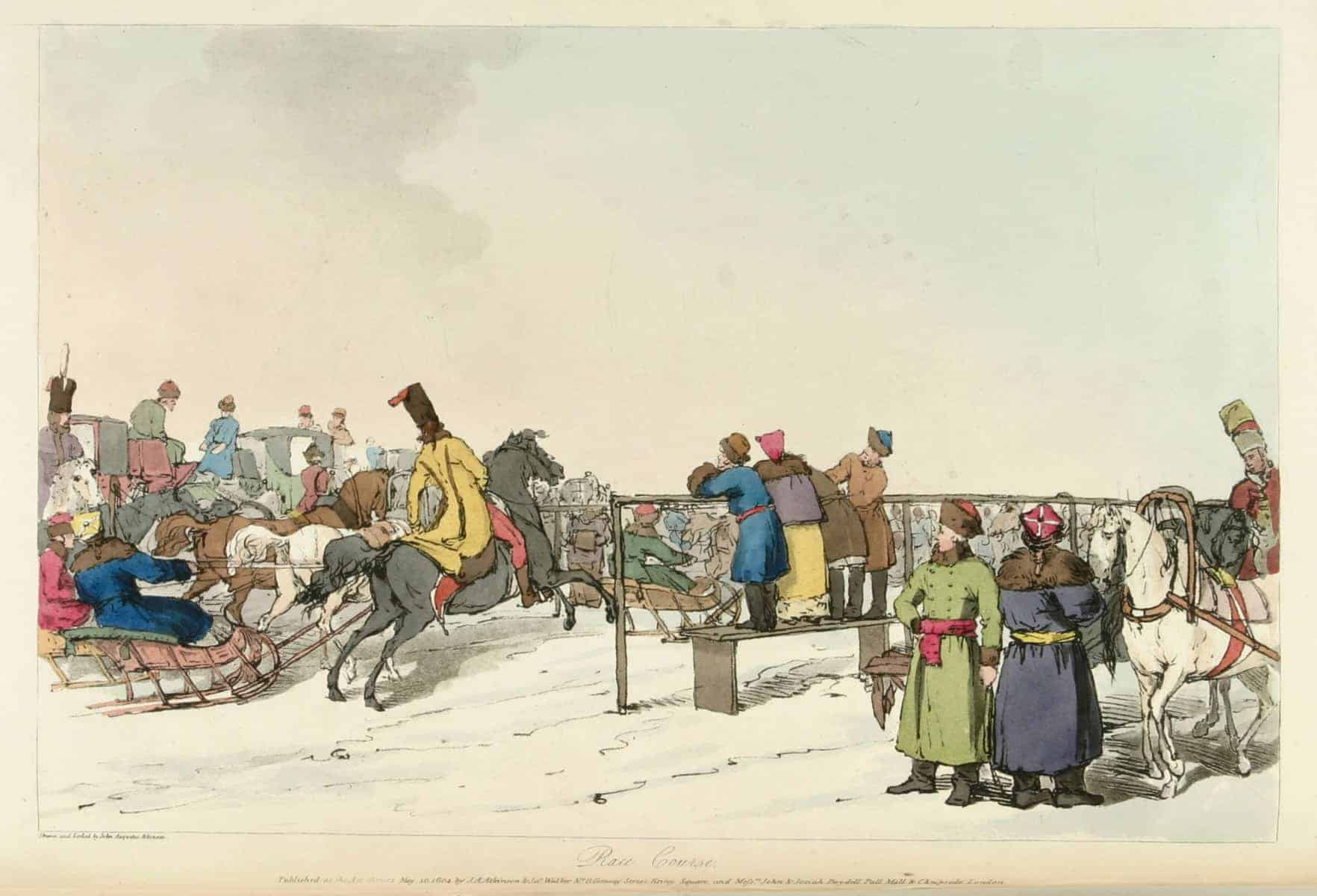

A special part of his oeuvre is a collection of sketches “A Picturesque Representation of the Manners, Customs and Amusements of the Russians”. The series, that was released as several notebooks and had more than one edition, was an important asset in promoting the image of Russia abroad. John Atkinson created 100 watercolour prints depicting Russian everyday life, with its entertainment, clothes and rituals. In his many illustrations Atkinson managed to convey the idiosyncratic traits of the Russian national character. This “ethnographic album” surpasses everything that was created before it in the breadth of the material it contains.

John Augustus Atkinson “Horse Races on the Neva River in Winter”. Photo: John Augustus Atkinson, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

A distinctive feature of this album is the abundance of plots related to labour. Atkinson annotated each illustration with explanatory texts in both Russian and English, in which the peculiarities of a foreigner’s understanding of the realities of Russian life are clearly visible. “Skiing down the icy mountains is a favourite pastime of Russians in winter, and even villagers, especially children, imitate big cities in doing this. To create such a slide, the slope of a small hill is levelled or a whole mountain of snow is put up and then poured over with water, which after freezing turns into ice. They slide down these icy slopes on small wooden sleighs to a great pleasure of those riding,” – Atkinson signed the engraving “Ice Slides for Children”.

Where to find:

- Tate Britain, London

- Saint Michael’s Castle, Saint Petersburg

- Pavlovsk Palace, outside Saint Petersburg

Julia Lapran

Cover photo: “Children with a Parrot”, Hermitage Museum, Christina Robertson, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Read more:

Antonio Canova’s ‘Three Graces’: Crafting a Neoclassical Masterpiece

Composer Alexander Scriabin: a journey from earthly melodies to celestial aspirations

Bakst, Benois and Dobuzhinsky: How an Extensive Collection of Russian Art Ended Up in Oxford

SUBSCRIBE

Receive our digest once a week with quality Russian events and articles