The secrets of the British Museum: the evidence of the Bible

The British Museum holds artifacts relating to the early civilizations of Sumer and Egypt. These exhibits to varying degrees confirm the authenticity of the events described in the Bible. To learn more about this unique collection, Afisha.London magazine and columnist Yulia Mints quizzed a former officer of the British Museum, Assyriologist Yulia Chmelenko, examined excavations in sun baked Muscat with archaeologist Dr. Jeffrey Rose and talked with a legendary Professor of Bible Studies at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Dr. Emanuel Tov. In the end it turned out to be a captivating investigation, the results of which will likely encourage you to visit the British Museum again to see the evidence of the Bible with your own eyes.

The British Museum is one of the most visited places in London. Though most of us are familiar with fascinating objects from Egypt and Assyria, some other significant, but inconspicuous items slip the visitor’s attention. Among them is a galaxy of pieces describing events found in the Bible. Intriguingly, these objects, dating thousands of years before the Bible appeared, belong to the early civilizations, Sumer and Egypt, which at first glance are little related to monotheistic religions. Some events from the Old Testament such as the Flood replicate in minute detail the Sumerian myth known from 2000 BCE.

Follow us on Twitter for news about Russian life and culture

When was the Bible written?

Most artefacts depict events of the Old Testament, which is, in its turn, based on the Torah. So, answering this question, we must keep it in mind. I had to head to Dr. Emanuel Tov in Jerusalem to find an answer:

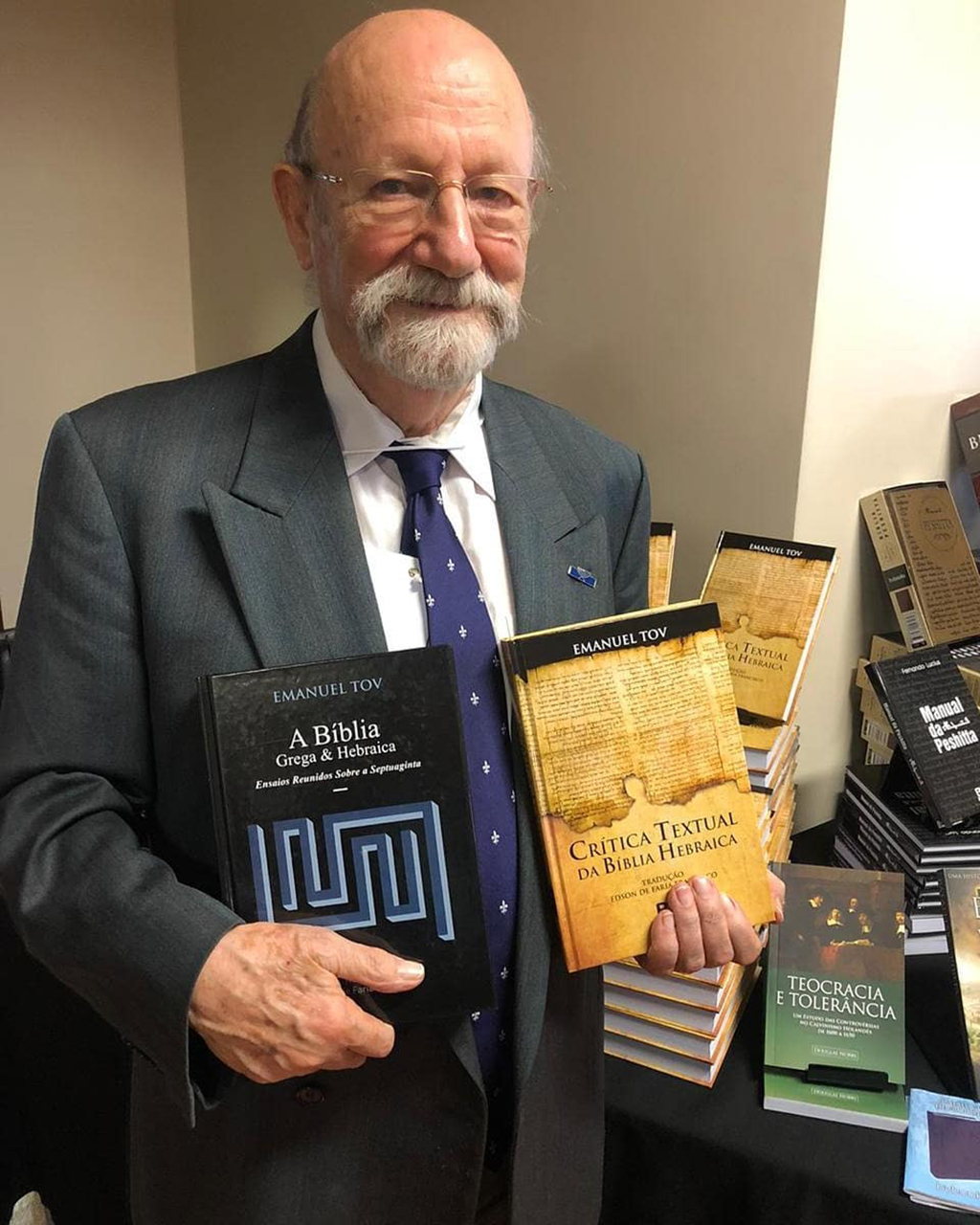

Dr. Emanuel Tov, J. L. Magnes Professor of Bible Studies at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem

We don’t know when the books of the Hebrew Bible were written, but we know when the latest books were produced. Scholars perceive it was the book of Daniel, II BCE. The books were written as late as II, IV and V BCE. Was there any writing prior to that time? Yes, we believe that books were also written in V, VI, VII BCE. The question if a book of Torah was written at that time is debatable.

I think this was written down VIII or VI BCE, because the twenty-third chapter of the Book of II Kings in the Hebrew Bible already talks about the copy of the Torah, which was found in the Temple. However, we don’t know the content of that Torah.

We also do not really know who the authors of those books were. Prophets, priests, the religious groups in Ancient Israel. The story of the Torah was based on oral tradition.

The books of the Old Testament and Torah were never written on clay tablets, but on leather and papyrus scrolls. The preserved materials from the Judean Desert are on leather scrolls. Some scholars believe the earliest texts were written on papyrus, but never on stones.

Why do we find parallels between the biblical stories and the myths of ancient civilizations?

When in 1872 a researcher of the British Museum, George Smith found a scrap of tablet containing the missing part of the Flood story, the public was literally stirred up. Not only because this might confirm the biblical stories, but because the text was nearly a thousand years older than Genesis. Prior the discovery, the Bible was considered the oldest and most authoritative book in the world. Intriguingly, other findings revealed parallels in the myth of the Fall of Man between Sumerian and biblical stories. The situation was made more acute by the fact that scholars didn’t know what place Sumerians came from to southern Mesopotamia. By the way, it is still one of the biggest mysteries. How were these stories transmitted to the Torah and the Old Testament?

Attempting to answer that question led me to Oman, where for many years an archeologist Dr. Jeffrey Rose has carried out excavations. Thanks to his research on the prehistory of the Arabian Peninsula, we know that the desert was green at that time and a particularly fertile territory submerged by the Persian Gulf may have been host to humans for over 70,000 years before it was swallowed up by the Indian Ocean around 8,000 years ago.

According to Dr. Rose, this transmission of creation stories into Hebrew might be explained by the oral tradition of nomadic semitic tribes spread across the Peninsula to the Levant.

Dr. Jeffrey Rose, Archaeologist and Anthropologist

“The ancestors of the Israelites would have told these tales around campfires for thousands of years before adopting a writing system. The demographic stability of Arabia, the emphasis on storytelling as a form of transferring information and the geographical isolation of the Peninsula made it possible.”

Dr. Emanuel Tov adheres to the same position: “The oral tradition is also influenced by traditions outside of the land of Israel. The culture of the ancient Israelites was influenced by the people living around ancient Israel, both from Ugarit (Syria), and from Mesopotamia. For that reason, we find many parallels between the literature of Israel and literatures of many peoples around ancient Israel.” Tablets and other artefacts found in Ugarit, Mesopotamia and Egypt are spread across the museums of the world, but most of them are at hand — at the British Museum.

Jeffrey Rose. Photo: David Foster Management

1. The Flood Myth: Epic of Gilgamesh and Epic of Atrahasis

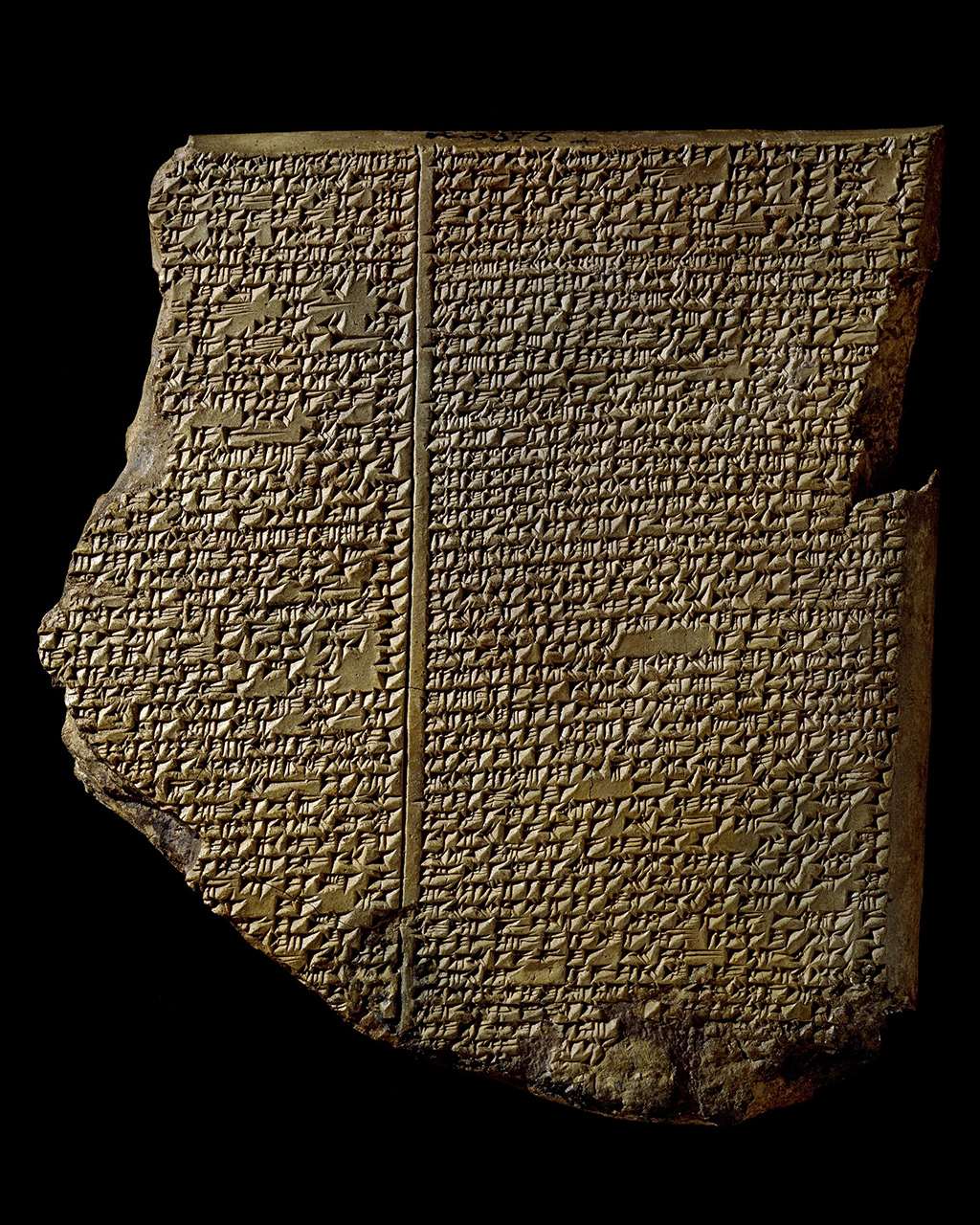

The Epic of Gilgamesh is about the adventures of a Mesopotamian superhero consisting of 12 tablets, the 11th of which is of the greatest interest. Tablet XI of this series was found during the excavations of the Royal Library of Ashurbanipal in Nineveh by Austen Henry Layard in the XIX century. In 700 BCE the Assyrian Empire is in decline. Ashurbanipal decides to remind Mesopotamia all this glory by creating a great library and putting together an amazing collection of literature, among which was a story of Gilgamesh. After Ashurbanipal dies, his palace is burnt to the ground creating a giant kiln, which totally preserved clay tablets with these literary pieces. Here, in the ruins of the palace in Nineveh, Henry Layard found them, and then a pioneering English Assyriologist from the British Museum George Smith translated them.

Yulia Chmelenko, Assyriologist, Art Historian

“Intriguingly, it was a reference to Nineveh in Genesis that encouraged scholars to launch a search of the biblical city.”

Although the tablet XI is relatively late, dated to VII BCE of Assyria, a narrative itself appeared in 2000 BCE in Sumerian mythology before being transmitted to the Bible as a story about Noah’s Ark.

- Emanuel Tov. Photo: BV Books

- Clay tablet, fragment of “Epic of Gilgamesh” © The Trustees of the British Museum

The tablet tells how the gods determined to send a flood to destroy the earth, but one of them, Ea, revealed the plan to a mortal named Utu-napishtim, who he instructed to make a boat in which to save himself and his family. He orders him to take into it birds and beasts of all kinds. Utu-napishtim obeyed and when all were aboard, all the rest of mankind perished. After six days the waters abated, and the ship grounded. The first bird released “flew to and fro but found no resting-place”. A swallow likewise returned, but finally a raven, which had been sent out, did not return showing that the waters were receding. Utu-napishtim, who later told this story to Gilgamesh, thereupon emerged, and sacrificed to the gods who, angry at his escape, granted Utu-napishtim on the intercession of Ea, divine honours and a dwelling place at the mouth of the river Euphrates.

There is a similar story in more ancient Sumerian myth of Ziusudra, 1800 BCE, and in a Babylonian Epic of Atrahasis, 1700 BCE. The latter is a point of particular interest, because the combination of clay with blood in the account of the creation of man reflects similar ideas to those found in the Old Testament where man is described as having been formed of ‘dust’ or ‘earth’ to which he would return.

Today scholars believe that floods were not rare in Mesopotamia at that time. They were caused by fluctuations of the water level in the Persian Gulf and spring snowmelt in the mountains of Zagros which flooded the rivers of Tigris and Euphrates. According to Yulia Chmelenko, the greatest flood was in the city of Ur, where 20 meters layer of silt was found during the excavations by Henry Layard.

Yulia Chmelenko. Photo: Natalya Malyhina

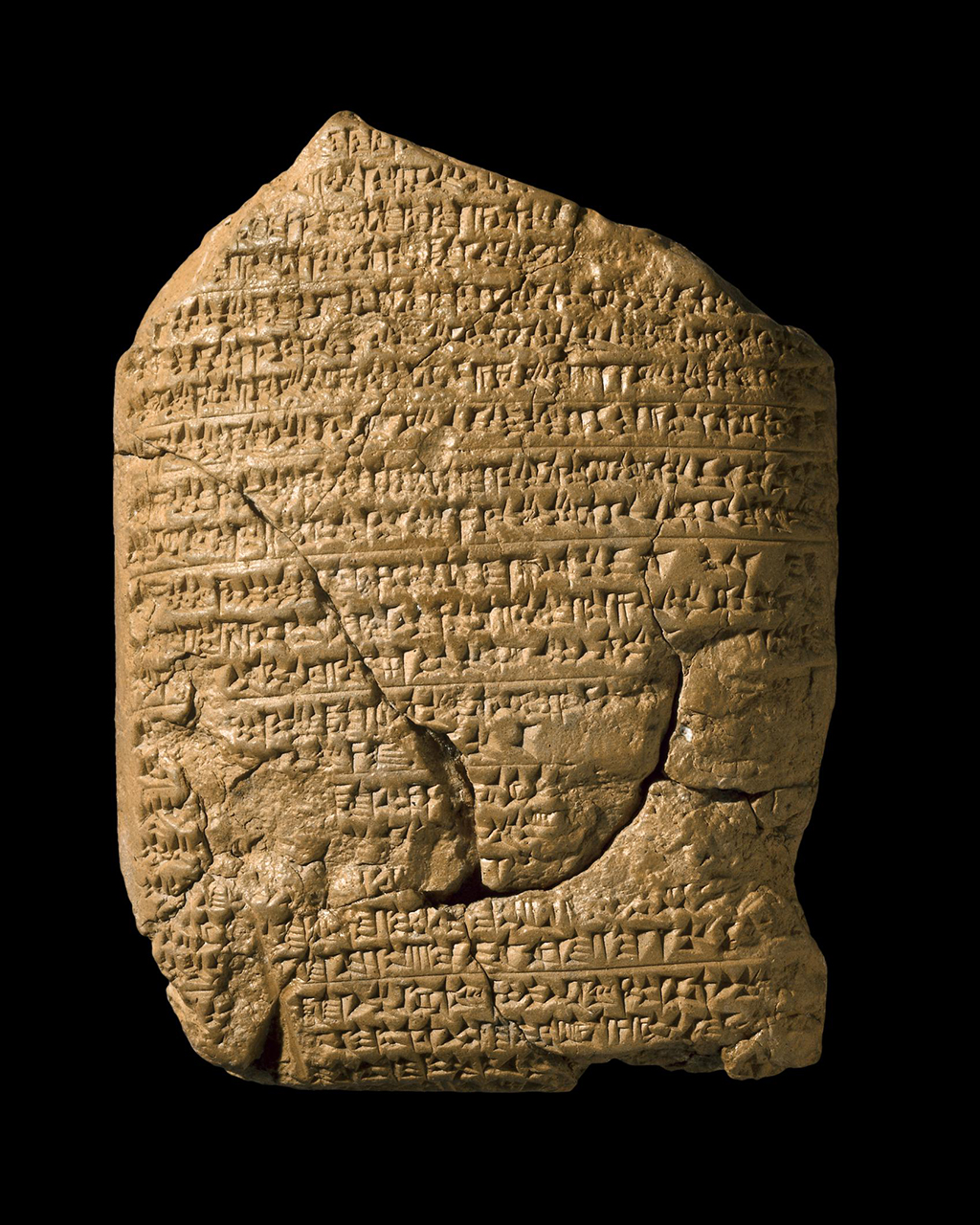

2. Nebuchadnezzar’s chronicle tablet and the Tower of Babylon

Many scholars believe that a story of the Tower of Babylon was inspired by Mesopotamian ziggurats, temple pyramid-shape towers. One of the best-preserved examples is that excavated by Sir Leonard Woolley at Ur on behalf of the British Museum and the University Museum, Philadelphia in the XX century. It was a ziggurat at Ur that was likely a prototype of the Tower of Babylon.

The reconstruction of one of the most famous ziggurats in Babylon began after the conquering of Jerusalem by Nebuchadnezzar II in 597 BCE. The king forced enslaved people to move to build the temple. In VI BCE the king Cyrus I of Persia occupied Babylon and freed the Hebrews. Most of them left this territory for Israel, probably, carrying away Mesopotamian legends. Today the ziggurat at Babylon is represented largely by a water-and-reed-filled hole in the ground and remains of baked bricks.

Read more: From Britain to Russia: a tradition of “Stonehenges” across Europe

3. Brick of Ramesses II

This inconspicuous, but significant artefact helps to identify the period of the biblical Exodus, which Jewish people all around the world celebrate as Passover. According to the Torah, a pharaoh sends Israelites to build two big cities in Egypt with ‘mortar and bricks’ and requires them to collect straw for this as an extra duty. Those bricks were made of Nile mud with chopped straw as a binder. Archaeologists managed to identify the exact place where these cities were built, one of which Raamses is a mainly farmland today. The magnetometer survey with selective excavation has revealed a large city with palace areas, stabling for horses and chariots, probable workshops, and extensive settlement. Intriguingly, scholars found that buildings were made with mud and straw bricks stamped with a cartouche containing a part of the official name of Ramesses II. The Pharaoh of the Exodus is not named in the Old Testament, being referred to only as ‘par’oh’, but Ramesses II is the only likely ruler.

- Clay tablet, Nebuchadnezzar’s chronicle © The Trustees of the British Museum

- Mud brick stamped with cartouche of Ramses II © The Trustees of the British Museum

4. Sodom Pottery

In the Bible people from Sodom and Gomorra were punished for wickedness by destroying their cities with a rain of fire and sulfur. Although the exact location of the cities is not still identified, some scholars believe that a site of Bab ed-Dhra in Jordan is the most likely. A search for legendary biblical cities was launched as early as in 1960s near the Dead Sea. In the 2000s American archaeologists perceived that Sodom might be found on the site of the Bronze Age of another Jordan city — Tall el-Hammam. Recent studies in 2021 have revealed that Tall el-Hammam was devastated in 1650 BCE by a cosmic airburst, which exploded over Tunguska, Russia, where a 50-m-wide bolide detonated with 1000 times more energy than the Hiroshima atomic bomb. According to an Assyriologist Yulia Chmelenko, there were found melted pottery and mudbricks, the surfaces of which were literally transformed into glass under the super temperature of about 2000°.

Sodom Pottery © The Trustees of the British Museum

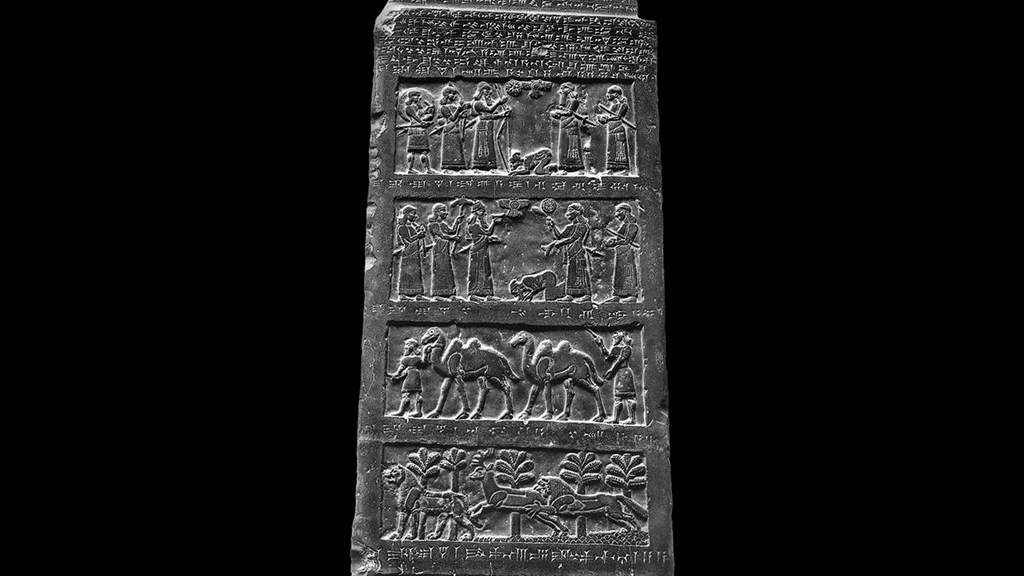

5. The Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser III

One of the most fascinating discoveries of the XIX century is an object visitor often miss. The black obelisk is richly decorated with five rows of relief sculptures depicting offering tribute to the Assyrian king Shalmaneser III from five rulers of the conquered territories. Of particular interest for Biblical Archaeology is the second series of sculptured relief, because the caption above these identifies the scenes as representing the Israelite king Jehu bringing tribute to Shalmaneser, an event not mentioned in the Bible. Furthermore, this is the only portrayal we have in ancient Near Eastern art of an Israelite or Judaean monarch.

Read more: Innovator and romantic Vladimir Nabokov in Britain

In the Bible the King Jehu is well known as a fighter with idolatry and the worship of Baal, a prototype of the Devil. In IX century BCE the Israelite king Ahab along with his wife, a Phoenician princess Jezebel, instituted the worship of Baal and Asherah on a national scale. They formed a congregation of worshippers, constructed temples, where blood human sacrifices were regularly made, and violently purged the prophets of the biblical God from Israel. Then the prophet Elijah dared to defend the Hebrew God and entered confrontation with the king Ahab. Elijah performed miracles to convince the ruler, but the latter remained loyal to a dark deity. Attempting to stop a cruel king, a successor of Elijah, the prophet Elisha, called an Israelite military commander Jehu and anointed him as king to struggle with the house of Ahab. Jehu, who is depicted on the black obelisk, tricked all worshippers of Baal into gathering in one place and killed them. After that, he destroyed their idols and temple, and turned the temple into a latrine.

On the Black obelisk the King Jehu might be easily recognized by a tall nightcap-like headdress. On this scene he is depicted as kissing the ground in front of Shalmaneser III and presenting generous gifts, among which are unusual animals reassembling sphinxes. An Assyriologist Yulia Chmelenko points to an interesting detail: “This was a likely way how Assyrian craftsmen imagined monkeys. These animals are not naturally occurring in Assyria, but they might be seen in the King’s Zoo, where craftsmen were not allowed. They were likely to depict monkeys from the stories of people who saw these unusual animals. For this reason, they look so weird.”

Black limestone obelisk of Shalmaneser III © The Trustees of the British Museum

These are just a few items of the seventy artefacts from the British museum. Most of them might be read about in the book by Terence Mitchell, a former Keeper of the Department of Near East — The Bible in the British Museum: interpreting the evidence. There is Goliath’s scale armour; an inscribed sphinx from the Hathor Temple with an early form of the alphabet, which led to many modern ones including Latin and Greek; and even The Codex Sinaiticus, which was obtained by an expedition of the Russian Empire and then sold to Britain by the soviet authorities in 1933. Besides, a story of the latter was brilliantly presented by Dr. Jeffrey Rose in a BBC documentary The Bible Hunters.

Afisha.London is grateful for contribution to the article:

Dr. Emanuel Tov, J. L. Magnes Professor of Bible Studies in the Department of Bible at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem; Appointed Member of the Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities; Appointed Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences; Appointed Corresponding Fellow of the British Academy.

Dr. Jeffrey Rose, Archaeologist and Anthropologist; Research Scholar of the Ronin Institute (Montclair, USA); Emerging Explorer of the National Geographic Society; TV presenter of BBC documentaries.

Yulia Chmelenko, Assyriologist, Art Historian; Member of The International Association for Assyriology; Member of the British Antique Dealers Association; Member of Russian Association of Art (AIS).

Cover photo: Ziggurat of Ur (Geena Truman)

Read more:

Alexander J Gifford “We’re standing up for Russian culture”

Elizabeth II and Russia: a visit to Moscow, a box for Yeltsin and the impressions of eyewitnesses

Mikhail Reznikovych: “Even now, in wartime, people visit the theatre”

SUBSCRIBE

Receive our digest once a week with quality Russian events and articles