Emmeline Pankhurst in St. Petersburg: The Suffragette Movement in Britain and Russia

Did you know that the suffragette movement and Wimbledon Championships have something in common? In addition to being united by London, there is another thing that brings them together – their official colour schemes. Contrary to popular belief, the first feminists were by no means sullen old maidens, who looked like Shapoklyak – villain from the famous Russian children’s book about Cheburashka. Feminism originated among wealthy, married and content women, who were supported by their husbands in the struggle for women’s rights. The leader of the suffragettes, Emmeline Pankhurst, even visited St. Petersburg, lived in Hotel Astoria, met with Russian feminists and inspected the legendary Women’s Battalion of Death. Afisha.London magazine explores the history of women’s movements in Great Britain and Russia and covers the visit of Pankhurst to the Russian capital in 1917.

This article is also available in Russian here

The birth of the movement for women’s suffrage

The first revolutionary activity in the struggle for women’s rights was launched by the French writer Olympe de Gouge at the end of the 18th century – her Declaration of the Rights of Woman and of the Female Citizen and the ideas of feminism resonated with audiences in different countries. The next wave of the already organised movement for women’s rights arose in the middle of the 19th century and was especially prominent in Great Britain, where a rigid class system reigned.

Mass protests gained momentum after the speeches of John Stuart Mill, a member of the British Parliament and one of the most influential philosophers of the 19th century, who championed the idea of individual freedom and called for the right to vote for women. In 1865, his famous essay The Subjection of Women, based on the ideas of one of the first feminists, his wife Harriet Taylor Mill, was published. The couple expressed the opinion that the principle of legal female subordination is false and impedes the progress of mankind. Four years later, the book was translated and published in Russia.

At the beginning of the 20th century, London became the epicentre of violent suffragette protests – this was the term journalist Charles Hands used to describe the activists in his article published in The Daily Mail. The founder and leader of the movement was Emmeline Pankhurst, who belonged to the so-called radical suffragette camp. Emmeline was born on 15 July 1858, into a respected politically active family in Manchester, and liberal sentiments surrounded her since childhood. But the idea of fighting for women’s suffrage, oddly enough, was proposed by her husband, lawyer Richard Pankhurst, who in every possible way contributed to his wife’s involvement in political activities.

Read more: Flappers: Emancipated Women of the 20s in the West and in Russia

On 10 October 1903, Emmeline, along with her two daughters, Sylvia and Christabel, and other suffragettes organised the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU). Their slogan was the phrase “Deeds not Words”. The members of the union came to the conclusion that legal methods no longer work and it is necessary to fight for women’s rights with the help of demonstrations, strikes, smashing windows and even committing arson in public places.

Needless to say, Pankhurst and other activists were extremely popular with the police: they repeatedly ended up in prison where they always went on hunger strikes. However, over time, Pankhurst’s authority noticeably weakened: many of her comrades-in-arms ceased to share such radical ideas, so Emmeline went to Russia.

After selling her home, Pankhurst travelled constantly, giving speeches throughout Britain and the United States. One of her most famous speeches, “Freedom or death”, was delivered in Connecticut in 1913. Photo: Topical Press Agency, photographer unknown, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Pankhurst in Petrograd

The emergence of the feminist movement in Russia is associated, first of all, with the abolition of serfdom in 1861. Rich noble families were close to ruin, so women were forced to look for additional income, get an education and find their place in the new world. Ladies from high society became doctors, nurses, midwives, journalists and translators – one of the most prominent activists was the writer and advocate for women’s education Maria Trubnikova.

Read more: Yehudi Menuhin in London: prodigy, violinist and goodwill ambassador

Many moved to St. Petersburg, which became the centre of Russian feminism: the homes of most feminists were located on Nevsky Prospect. In 1917, Russia was engulfed in the chaos of the Revolution and the First World War, and Emmeline saw her mission in supporting the fighting spirit of Russian women and in a subsequent triumphant return to Britain.

On 18 June 1917, Pankhurst arrived in Petrograd (St. Petersburg was renamed in 1914) and stayed in the Russian capital for three months, which were full of meetings not only with various women’s organisations but also with representatives of the Russian elite and members of political parties.

Emmeline Pankhurst. Photo: PA Images / TASS

Their first days in Petrograd Emmeline and her secretary Jessie Kenney spent at the Angleterre Hotel, but then moved to the safer Astoria, where almost all foreigners stayed. Pankhurst was well known in Russia: the public was familiar with the uncompromising rebel through articles in the newspapers Russkaya Volya and Novoye Vremya; moreover, her autobiography My Own Story was also translated into Russian. A circle of loyal female fans quickly formed around the charismatic leader of the suffragettes – they queued to get her white bread, which then was a rare delicacy, and cleaned her room when Astoria’s employees went on strike.

Read more: Virginia Woolf and Her Fascination with Russian Literature

The entire British diaspora of Petrograd considered it their duty to pay a visit to the famous Englishwoman, while female translators brought her newspapers every morning, so that Emmeline was aware of all the latest events. In honour of Pankhurst, a banquet was organized at Astoria, which was attended by representatives of women’s movements, including the first Russian female doctor, Anna Shabanova, and one of the first Russian female officers – the commander of the Women’s Battalion of Death, Maria Bochkareva. Emmeline conducted an inspection of the battalions and was pleased with what she saw. The teams were formed from female volunteers with the aim of raising the patriotic spirit of the soldiers by their example; they even took part in hostilities, which corresponded with Pankhurst’s ideology.

- Emmeline Pankhurst. Photo: Library of Congress, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

- Emmeline Pankhurst and Maria Bochkareva (1917). Photo: Everett Collection / East News

In a friendly and pleasant atmosphere, Pankhurst met with the leader of the Mensheviks Irakli Tsereteli, the Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Provisional Government Pavel Milyukov and the eccentric prince Felix Yusupov. Suffragette and journalist Rheta Dorr, who was present at most of Emmeline’s meetings, wrote: “Mrs Pankhurst was very well received in Russia. They wrote about her in newspapers, officials met with her, the best women of Petrograd were in a hurry to get to know her”.

However, Florence Harper, another foreign correspondent and adversary of the suffragettes, expressed a different opinion. According to her, Pankhurst’s mission was unsuccessful, because, despite the general admiration for the English suffragette, feminism turned out to be self-sufficient in Russia and did not need any outside help. The same opinion was shared by Minister-President Alexander Kerensky, with whom Emmeline met in August – the politician did not support her ideas, considering them alien to the Russian reality. In September 1917, Pankhurst returned to Great Britain and began giving lectures about Russia.

Read more: Anna Akhmatova in the UK: A Poetess, Muse and Femme Fatale

The colour scheme: what unites suffragettes and Wimbledon Championships?

In magazines and newspapers, suffragettes were often portrayed as eccentric old maids in sloppy clothes and huge glasses. Such cartoons were drawn by the artist John Tenniel, the author of the iconic illustrations for Alice in Wonderland, and in such way the activists appeared in the imaginations of many. In reality, however, the suffragettes felt it their duty to look as elegant as possible in order to draw attention to their demands and recruit new members. They even had official colours: violet represented dignity, white stood for purity of thoughts and freedom, while green was a symbol of hope. The first letters of the colours formed into GWV (Green-White-Violet), which was an abbreviation of the slogan “Give Women Votes”. Interestingly, the official colours of Wimbledon Championships are green and purple, while the athletes traditionally wear white uniforms.

- A WSPU postcard album with their slogan. Photo: LSE Library

- A medal given to a suffragette for surviving a hunger strike in 1912. Photo: LSE Library

There were suffragette-friendly department stores in London, Selfridges and Liberty, which sold abundant merchandise in the three colours: ribbons, hairpins, jewellery, handbags and hats. Any woman could wear a green-white-violet brooch and thereby demonstrate her sympathy for the women’s movement. Nowadays, politicians continue to use colours as symbols: for example, in 2015, former US First Lady Hillary Clinton appeared at the election debate in a snow-white suit, while her supporters also wore white, which was synonymous with opposition.

The media interpreted this a tribute to the suffragettes – no American woman has ever been so close to presidency. The British TV series Mr Selfridge perfectly shows how quickly suffragism was gaining momentum in London. Feminists adored Harry Selfridge’s fashion store but remained true to their ideals – Selfridges was not spared during window-smashing rallies. However, there are opinions that demonstrations were mainly attended by specially hired working-class women, who acted as extras.

Read more: Russian Emigration a Hundred Years Ago and Now: What United the Two Generations

Have the efforts of the suffragettes paid off?

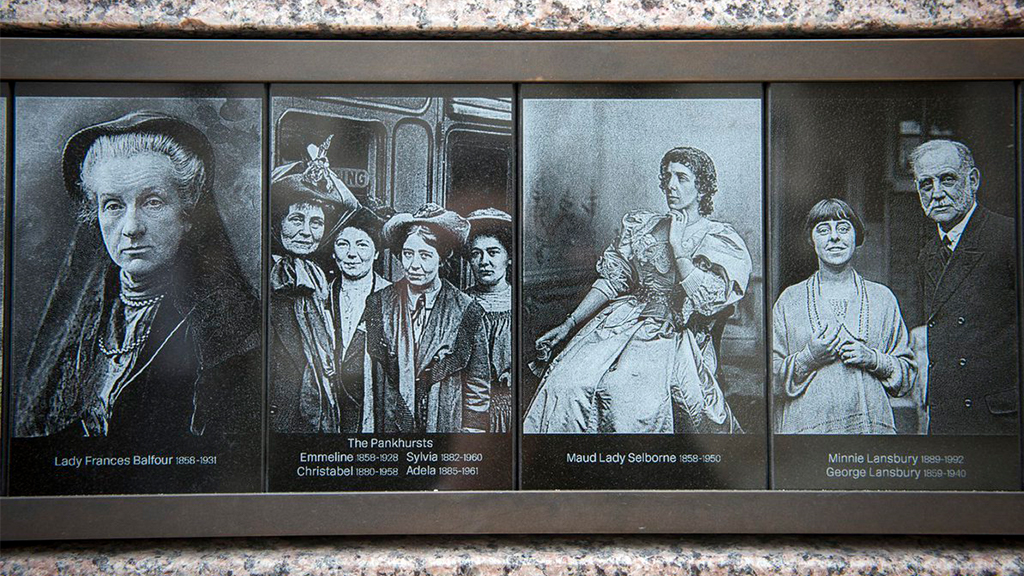

Most feminists were respected middle-class ladies: notable supporters of Pankhurst were the fearless Evelina Haverfield, the wealthy couple Emmeline and Frederick Pethick-Lawrence, the successful female lawyer Elsie Bowerman and the female physician Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, who won the right to enter medical school for women and became the first female Mayor in the history of the United Kingdom. Moreover, it was Frederick Pethick-Lawrence who was billed for broken windows – until 1912, the couple were the main sponsors of the suffragette movement. Baroness Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, as well as other 58 suffragettes, are immortalised on the pedestal of the Millicent Fawcett statue in Parliament Square in London, which was opened in 2018.

Fragment of the pedestal of the Millicent Fawcett statue in Parliament Square. Photo: Mayor of London

Historians have not come to a consensus on whether the radical measures taken by Emmeline and her followers were justified and whether they accelerated the adoption of the Act on the Equal Status and Equal Rights of Women and Men. After returning from Russia in 1917, Pankhurst did not manage to gain her authority back and switched to a political career in Canada. The most famous suffragette died in a nursing home in Hampstead on 14 June 1928 – the same year a law giving all women over the age of 21 the right to vote was passed in the UK.

In Russia, women received the right to vote 10 years earlier, in 1918. However, it is indisputable that Emmeline inspired thousands of women. The film Suffragette with Helena Bonham Carter and Meryl Streep celebrates her influence on the working class. There also are several monuments dedicated to Pankhurst: a statue called Rise Up Women is situated on St Peter’s Square in Manchester, while another bronze figure of the suffragette stands at the entrance to Victoria Tower Gardens in London.

Emmeline Pankhurst’s legacy continues to live on in the writings of her descendants – her distant relative Kate Pankhurst was so inspired by the story of her famous ancestor that she began writing books and creating illustrations on the theme of the women’s rights movement. Her work introduces children and adolescents to feminism and the stories of successful women in a fun way. The book Fantastically Great Women Who Changed the World by Kate has become popular in Russia.

Irina Latsio

Cover Photo: Afisha.London

Read more:

Dostoevsky in London and His Influence on the British Classics

Innovator and Romantic: Vladimir Nabokov in Britain

Composer Pyotr Tchaikovsky in London: Impressions, Recognition and Success

SUBSCRIBE

Receive our digest once a week with quality Russian events and articles