Curator Elena Konyushikhina’s explorations of post-Soviet representations of history, family, and the self

After the dissolution of the USSR, identity and self-awareness became important issues for many people: they had to quickly adapt to new conditions, and learn to live in countries with a new ideology, and a new structure of power. The hero of this article by Afisha.London is Elena Konyushikhina, a curator who explores issues of identity in the post-Soviet space in her projects.

Elena Konyushikhina’s curatorial projects deal with the central question of contemporary post-Soviet space, that of influence of history and familial background on lived identities. Apart from the self-evident difficulties of grasping a working definition of both “history” and “identity”, the process of reconciling the post-Soviet subject with their past has been controlled, sometimes in violent ways, by the governments of the region. In Russia and in the former Soviet republics of Central Asia the state archives, including that of KGB, USSR’s secret police, have not been opened to the public. It means that even personal inquiries into the destiny of one’s relatives become a nearly impossible task, and all cases of successful interactions with authorities are widely publicized. This lack of openness primarily has a political dimension: if you do not know who was on KGB’s payroll, you can’t make them answer for their crimes. If the former employees are not in danger of public ostracism or court proceedings, the newest recruits will be more eager to collaborate, if the need arises. Socialism or not, the state protects state-sanctioned double identities.

Oleg Koshelets, Flags, rakes & statue of Stalin. 2012. Courtesy Elena Konyushikhina

According to Valentin Diaconov, an award-winning art critic and curator at the Garage Museum of Contemporary Art, Moscow, who holds a PhD in Culture Studies, this lack of information and the atmosphere of secrecy makes art about the difficult heritage of the past a very bold gesture, both in terms of its clarity (it literally is a shot in the dark most of the time) and in terms of its political significance. Konyushikhina’s Voices (2015, A3 Gallery) makes this very clear. Alexander Kutovoy’s A Subject (2012), a clay bust with a destroyed face, is simultaneously a comment on rewriting the urban propaganda’s sculptural division after 1991 and a portrait of an abstract, unknown victim of Soviet-era policies.

Follow us on Twitter for news about Russian life and culture

Oleg Koshelets’ installation Flags, Rakes, and a Statue of Stalin (2012) shows the possibilities of dark history’s activation. The painful truth is that Stalin is not even a ghost in contemporary Russia: he’s often depicted either as an «effective manager», to link industrialization to the current neoliberal regime, or an «architect of Victory», the overarching deus ex machina for Russia’s success in the Second World War. Given the number of people directly affected by his rule, it is perplexing that this figure is still on the brink of rehabilitation. By skillfully steering public opinion towards uncritical respect for any and every «forceful» leader of Russia’s past, the ideologists of today have plunged the county towards a kind of historical Darwinism in the most primitive sense. And the power that is lionized by the official propaganda committed all the violent acts in the past not in the name of the people, but in the name of the country, an entity that is comprised of territory, army, and infrastructure. It is fitting, then, that sculptor Igor Shelkovsky proposes to erect a labor camp watchtower as monument to the victims of the Great Terror. A dark structure’s only function is to loom over thousands of nobodies, people without a right to their own identity. But the watchtower is empty: the one who’s watching has no identity either.

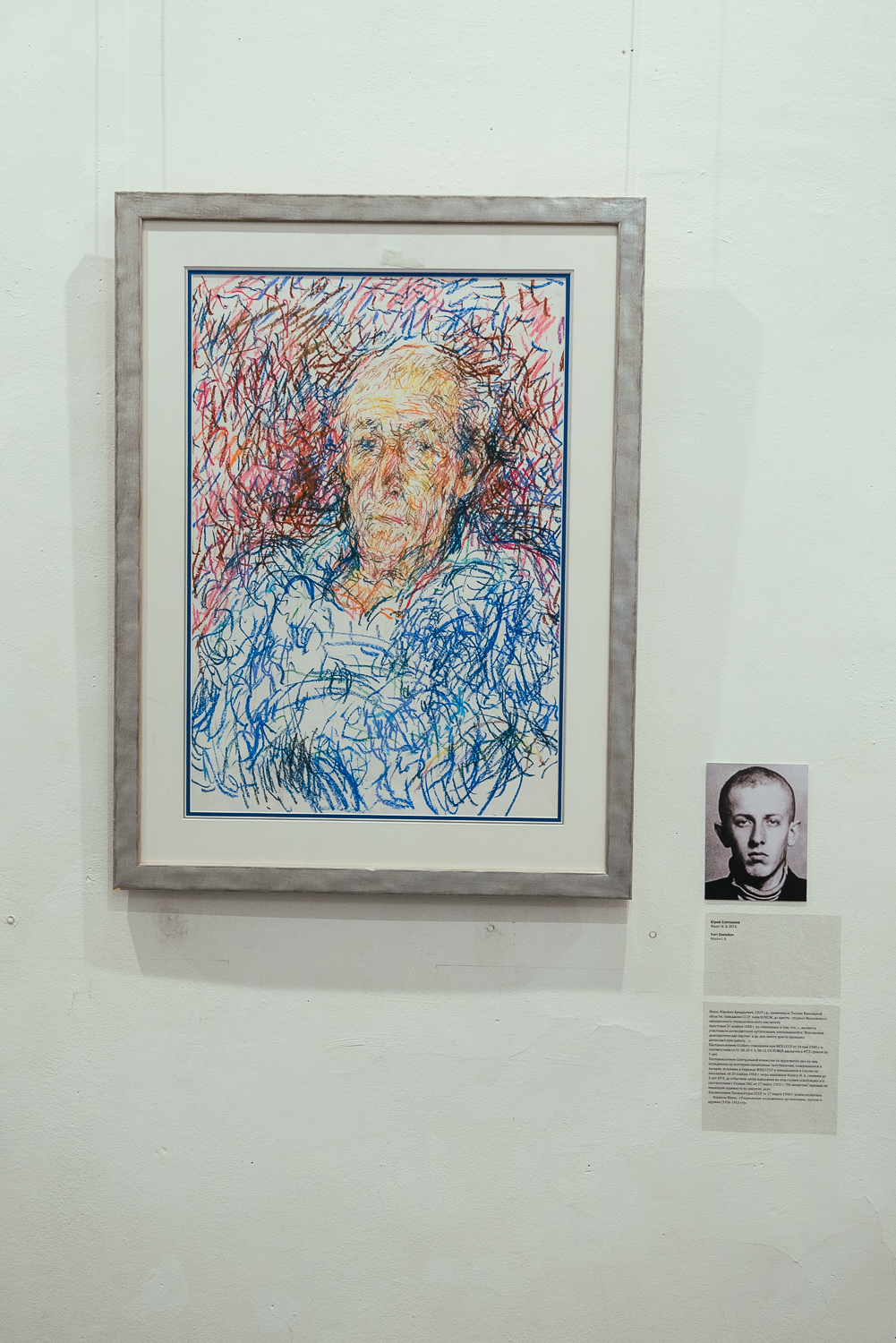

- Yuri Zlotnikov, Mazus I. A. Courtesy Elena Konyushikhina

- Padded jacket and boots. Belonged to Coral M.M. Steplag (pos. Kengir ). Gift of Coral M. M. Memorial collection. Courtesy Elena Konyushikhina

The names are erased in Ekaterina Muromsteva’s Names (2015), poet Osip Mandestam’s is but a number in Alexander Elmar’s graphic work, and the era of Stalin itself becomes a lattice in Yury Zlotnikov’s piece. Voices, then, is a clear message of embodiment at the heart of the past, a sign of a biography, a life, and this message is underscored by inclusion of real objects, belonging to the former camp inmates, from the Memorial Society’s archive.

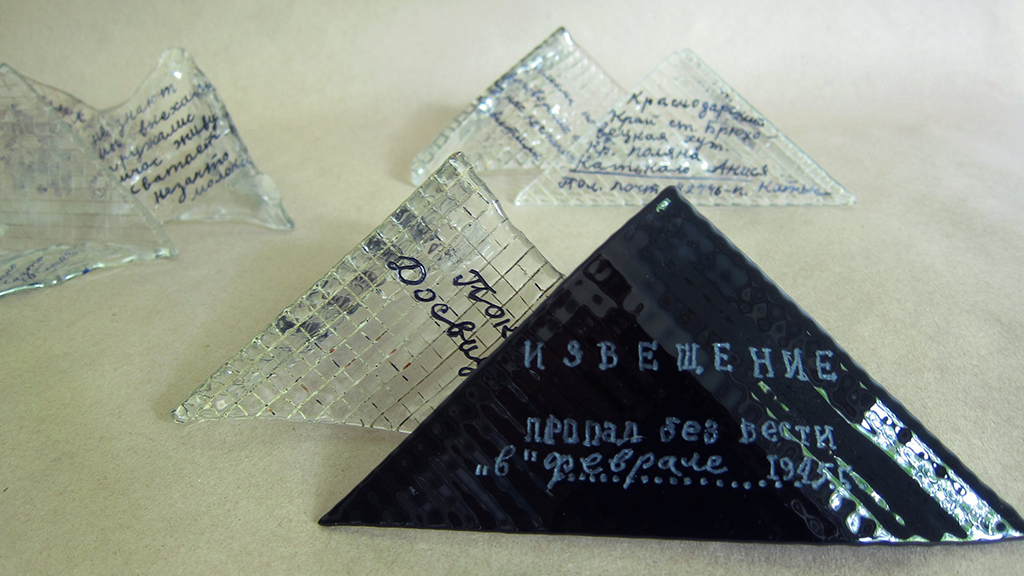

A clear path towards one’s identity, then, is narrow. For many, it’s the immediate intimacy of the family album that provides at least a semblance of continuity. «Family Archive», Konyushikhina’s 2018 project for Theater am Stieg in Baden, is a collection of work that explores that continuity. Alyona Kalyanova’s sculptures are based on her grandfather’s letters from the WWII frontline. The series ends with his death certificate. Yanina Chernykh turns that staple of homeliness, the teddy bear, into a diaristic object: the toy animal’s leg bears an inscription «I do not like my distant relatives».

Alena Kalyanova, Letters from my great-grandfather. 2014. Glass, sintering, deflection, engraving, painting. Courtesy the artist

Igor Samolet plays games with his nephew, documenting the everyday performativity of familial friendship. As a rule, family past is a difficult subject for artists to employ with any kind of cogency. Personal closeness to a subject gives an illusion of default depth to an artistic gesture, but the artists in Family Archive go out of their way to transform individual content into form that comments on memory’s transformations and meanings. A family document is never just a document, it is an intimate gaze at a meaningful relationship.

It seems logical that Konyushikhina’s most recent curatorial project concerns artistic self-portraits. About Me, Please, About Me (25Kadr Gallery, 2018) is a survey of individual myths and representations. It is as if Konyushikhina’s strategy is a series of concentric circles, starting from the big historical outside and gradually arriving at the epicenter of artistic production, the figure of the artist. From the vast and scary terrain of collective past to the ambiguous comfort of the family album, the gaze turns on itself to reflect the identity in real time.

Installation view on Polina Rukavichkina’s series “Pink days and blue days”. 2016-17 and Olga Vorobyova’s “Girl who used to be”. 2017. Color printing. Courtesy 25 Kadr Gallery

It seems fitting that Konyushikhina’s next project plateau, a YouTube documentary series on artists in (imperial) capitals, London and Moscow, is going beyond self-representation into self-reflection on different geographies and temporalities that condition one’s artistic output. Konyushikhina’s contribution to the pressing questions of contemporary art life is very precise and at the same time topically expansive, and her future projects are sure to make even more realities and voices tangible.

Valentin Diaconov, an award-winning art critic and curator at the Garage Museum of Contemporary Art, Moscow. He holds a PhD in Culture Studies.

Cover photo: Installation view. About Me, Please, About Me. 2018. 25 Kadr Gallery. Courtesy 25 Kadr Gallery

Read more:

Digital autocracy in the work of Nata Yanchur

A film about Anna Politkovskaya will be filmed in the UK

Screenwriter of “The Crown” will stage a play about Russian oligarchs

SUBSCRIBE

Receive our digest once a week with quality Russian events and articles