Anna Akhmatova in the UK: A Poetess, Muse and Femme Fatale

In the 1960s, the world community recognised Anna Akhmatova’s unparalleled command of historical poetry – through her work she conveyed the ups and downs of the era and the tragedy of her fate. The British cultural elite and Oxford University in particular played a significant role in the popularisation of her art. Afisha.London magazine talks about the life of Anna Akhmatova – the last star of the Silver Age – and the Brits who fell in love with her as well as the honorary doctorate she received from Oxford University in 1965.

On the path towards an arduous fate

Anna was born on June 23, 1889 near Odesa in the Kherson Governorate into a noble family of a retired mechanical fleet engineer Andrey Gorenko. In the future, she would use a pseudonym, Akhmatova, since her father was against his daughter’s passion for poetry and forbade her from using the family name. Curiously enough, there were no books in Gorenko’s house, and Anna was introduced to the world of literature by her mother, who knew the poems of Nekrasov and Derzhavin by heart. Because of her rebellious nature Anna was often called wild as a child: she spent her summers near Sevastopol, where she shocked the local youths by swimming during a storm and sunbathing until darkly tanned.

In 1899, the girl enrolled in the Mariinskaya Women’s Gymnasium in Tsarskoye Selo (now Pushkin, a suburb of Saint Petersburg), where the Gorenko family moved. After her parents divorced, 16-year-old Anna settled with relatives in Kyiv, where she graduated from the Fundukleevskaya gymnasium and enrolled in the Higher Courses for Women to study law. There the girl corresponded with the poet Nikolay Gumilyov, who was in love with her and whom she met in Tsarskoye Selo. By that time, Gumilyov moved to Paris and published a magazine called Sirius, where Akhmatova’s work – a poem ‘On his hand you may see many glittering rings…’ – was printed for the first time. In 1910, the couple got married near Kyiv, in the village of Nikolskaya Slobodka, and went to Paris for their honeymoon. They later moved to Saint Petersburg where the poetess would spend most of her life.

Class of the Mariinskaya Women’s Gymnasium, 1904–1905. 2nd from the left in the 2nd row is A. Gorenko (Akhmatova). Photo: Tsarskoye Selo Gymnasium of Arts named after A. A. Akhmatova

In March 1912, Akhmatova published her first collection of poems called ‘Evening’, and on October 1, she gave birth to her son Lev. The years of the First World War were the beginning of a series of misfortunes that she would have to endure, and instead of focusing on love in her poetry she chose a more political approach. In 1918, Anna divorced Gumilyov, and in 1921 she lost him forever: the poet was accused of conspiracy and executed by firing squad. Anna lived with her second husband, orientalist scholar Vladimir Shileyko, for only a couple of years, and after getting a divorce officially changed her name to Akhmatova.

From 1922 to 1938, she was in a civil partnership with art critic Nikolay Punin. Anna would then write that ‘no generation had such a fate’. In the 1930s, Punin and her son Lev were subjected to repressions, and the poetess’ work was banned until 1939. The endless prison queues she had to wait in to get news about her husband and son inspired ‘Requiem’ – a poem dedicated to all the mothers and girlfriends of the so-called Soviet ‘enemies of the people’. It was first published by foreign media in 1963. In the USSR, the banned poem was published only in 1987, which was sensationally announced on March 21, 1987 by the The Guardian: for the Western world it was a sign that it was time for a change in the USSR.

Anna Akhmatova with her husband N. S. Gumilyov and son Lev. Фото: L. Gorodetsky, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The Englishmen who fell in love with Anna

After the Second World War, in 1946, Akhmatova was expelled from the Writers’ Union for five years because the establishment considered her poetry ‘pessimistic’ and ‘decadent’, depriving her of ration cards and the opportunity to get published. It is believed that Akhmatova was persecuted by Stalin’s ‘courtier’ Andrei Zhdanov, who called the poetess a ‘half-nun-half-harlot’.

In November 1945, a meeting took place in Leningrad that would later become legendary in literary circles, though it did make Akhmatova a suspect in the eyes of the Soviet government, for there were rumours that she had a romantic relationship with a so-called British spy.

Read more: Innovator and romantic Vladimir Nabokov in Britain

Isaiah Berlin, a diplomat who got a job at the British Embassy in Moscow, travelled to post-war Leningrad. When he learned that Akhmatova, known to him as a great pre-revolutionary poetess, lived nearby, he was set on meeting with her. Anna was 20 years older than him, but even at the age of 56 she was an elegant woman who could charm any man, while Isiah himself had a reputation of a ladies’ man. They talked until four in the morning: Akhmatova read him Byron’s ‘Don Juan’, and according to legend Randolph Churchill – the son of Winston Churchill – had to wait for Isaiah outside. According to some accounts, Isaiah returned to the hotel in the morning and threw himself on the bed with an exclamation: ‘I’m in love!’.

Their romantic meeting inspired multiple literary works (even though in fact they met more than once): Akhmatova’s secretary Anatoly Naiman wrote a novel called ‘Sir’, ‘Night Visit’ – a play by Jean Binnie – was broadcast by the BBC, and in 2011, a performance based on the play ‘Anna: Love in the Cold War’ by Nancy Moss was presented on Broadway. In December 1945, Akhmatova herself dedicated a verse to their date, and later recalled Isaiah in ‘A Poem Without a Hero’. In 2015, an exhibition was opened at the Pushkin House in London in honour of the nocturnal rendezvous curated by Nina Popova, director of the Akhmatova Museum in St. Petersburg, and Henry Hardy, a researcher of Berlin’s art based at Oxford University. Exactly 20 years after that legendary meeting in 1945, Isaiah Berlin would meet the poetess again in Oxford and become Akhmatova’s last love in the eyes of the world.

Read more: How Diaghilev’s ‘Saisons Russes’ influenced the European art world of the 20th century

- Petrov-Vodkin K.S., Portrait of Anna Akhmatova, 1922 (fragment) © The State Russian Museum

- N. Altman, Portrait of A. A. Akhmatova, 1914 (fragment) © The State Russian Museum

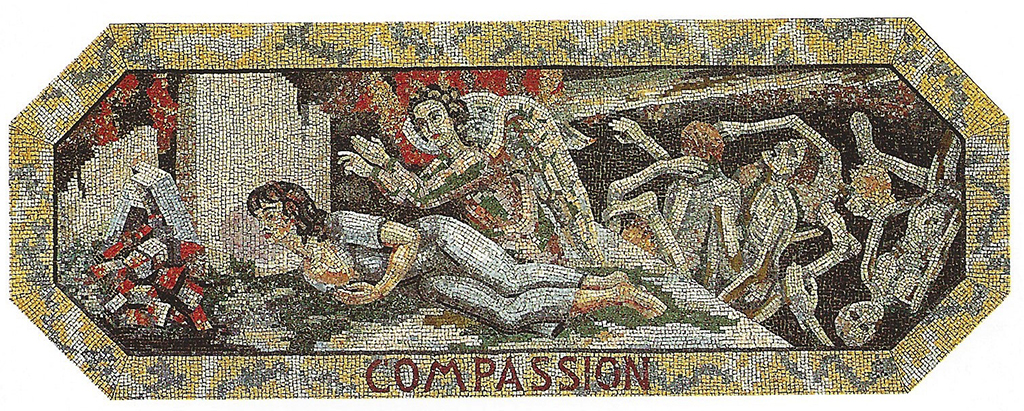

However, Anna Akhmatova is also credited with a passionate affair with yet another ‘Englishman’ – the charming Russian-born artist Boris Anrep, who specialised in mosaics. He met Akhmatova before the Revolution, and she gave him a black ring to signify her feelings, which he would later carry on a chain like a holy relic. Throughout their lives, they met only a couple of times, since Anrep spent most of his life in London and became famous there – among his mosaics can be found at the Tate and the Bank of England. It is believed that Akhmatova dedicated many of her poems to him, including ‘To Londoners’, which was written as a response to the bombing of the British capital in 1940. Anrep immortalised Anna and her memories of the besieged Leningrad in a mosaic: she spent the first year of the siege in the city and served as a firefighter. If you pay attention to the floor at the entrance to the National Gallery in London, you will find Boris Anrep’s work featuring Anna. In the centre of the mosaic called ‘Compassion’, that is dedicated to the victims of the besieged Leningrad, Anrep placed the figure of Anna Akhmatova and an angel blessing the poetess.

Boris Anrep, Compassion. Photo: Wojciech Karpiński

Akhmatova receives an honorary doctorate from Oxford

In the 1950s, Akhmatova’s life became much more bearable. The poetess was reinstated in the Writers’ Union, in 1956 her son Leo was released, while a year earlier she received a country house in the village of Komarovo from the Literary Fund – this was her first own home. In 1962, after 22 years of hard work, she completed ‘A Poem Without a Hero’, in which she reflected on the bygone era of the Silver Age, sin and redemption. Since the 60s, Akhmatova’s work has been widely recognised abroad – she was nominated for the Nobel Prize, and in 1964 she received the Etna-Taormina poetry prize in Italy, which in 2014 was renamed and became the Anna Akhmatova Prize.

Read more: Composer Pyotr Tchaikovsky in London: impressions, recognition and success

In the summer of 1965, six months before her death, 77-year-old Akhmatova came to the UK to receive her doctorate from Oxford at the invitation of the British Council. England applauded the ‘empress’ of Russian poetry – in old age Akhmatova resembled the majestic Catherine the Great. The pages of British newspapers were full of headlines dedicated to the arrival of the poetess and to her work. The Guardian published the tragic ‘Requiem’ on the front page; however, Akhmatova herself did not want to be involved in the publication of her banned poems.

At Victoria Station in London, Akhmatova was solemnly greeted by a whole delegation, and a young Slavist from the University of London, Peter Norman, was singled out as a translator – he was extremely proud of his important role. Akhmatova was accompanied by her ‘adopted granddaughter’ Anna Kaminskaya (Anna was actually the daughter of the poetess’s stepdaughter Irina Punina), who became a chronicler of their trip. The guests were accommodated in the President Hotel in Russell Square, where the poetess received so many dark red roses that their room became like a greenhouse. The next day, the ladies were taken to Oxford by Isaiah Berlin, who, 20 years later, still admired Anna and in a way made her trip to England happen. After a friendly dinner at Isaiah’s house, Akhmatova and her companion settled in the old Randolph Hotel, and on June 5, Anna Andreevna was awarded with an honorary doctorate by Oxford University. A crowd of admirers awaited the poetess in the foyer of the Randolph, and the remaining three days in Oxford flew by in a flash: a gala dinner with the Pasternak sisters, a reading of ‘A Poem Without a Hero’ in French for the BBC, meetings with Arkady Raikin and poet in exile Gleb Struve. The tour ended with two days in Stratford-upon-Avon, where Akhmatova visited Shakespeare’s Birthplace.

The Randolph Hotel. Photo: David Stanley from Nanaimo, Canada, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The poetess returned to the USSR through Paris where she met with Boris Anrep and put an end to their strange, undefined relationship. On March 5, 1966, Akhmatova died of heart failure in a sanatorium in Domodedovo: the death of an outstanding poetess was reported on the All-Union Radio, and she was buried in Komarovo near Saint Petersburg. Akhmatova’s poems have long been recognised as one of the greatest achievements of world literature. And if in the 1960s the Western public was more interested in the political aspect of her work, in the 1970s the focus shifted, and the sophisticated poetess was perceived as a psychologist, a master of historical poetry, and a conduit of eternal human values. This was facilitated by high-quality translations of her poems into English, conveying the poetic style of Akhmatova, and the publication in 1976 of a voluminous monograph ‘Anna Akhmatova: A Poetic Pilgrimage’, written by Amanda Haight and published by the University of Oxford.

Irina Latsio

Cover Photo: Olga Kardovskaya, Portrait of Akhmatova, 1914 (fragment) © State Tretyakov Gallery

Read more:

The legendary Russian children’s poet Korney Chukovsky in London

Felix Yusupov and Princess Irina of Russia: love, riches and emigration

SUBSCRIBE

Receive our digest once a week with quality Russian events and articles