Cinema is not a consolation pill: film director and screenwriter Andrey Zvyagintsev about creativity, international success, and life after a coma.

Andrey Zvyagintsev is a name that reverberates beyond the confines of Russian-language cinema, establishing a significant footprint on the international stage. A prestigious laureate of the Venice Film Festival’s highest honour, Zvyagintsev has also earned critical acclaim at Cannes. His brilliant films, ‘Leviathan’ and ‘Loveless,’ have received Oscar nominations, cementing his status as an influential filmmaker. Despite facing rigorous critique in his native Russia for his candid depictions of societal woes—imbued with existential unease and high-stakes drama—he remains firm. The onset of war in 2022 has disrupted traditional filmmaking paradigms, but Zvyagintsev’s resolve is unbroken. He continues to cultivate his cinematic artistry, even venturing beyond the borders of his homeland. Afisha.London magazine recently met with Zvyagintsev on the artistic meeting, eliciting his insights on the evolving socio-political climate, responses to the pervasive melancholy in his works, and contemplations on the nature of mortality.

On the Long Journey to Directing

Contrary to what many might assume, Andrey Zvyagintsev did not commence his career in the director’s chair but rather on the acting stage. He took the plunge into filmmaking only after crossing the age of 35. However, when reflecting upon his formative years, he underscores that his intrigue with the cinematic arts was already budding.

As a young lad between the ages of 8 and 10, he had the fortuitous opportunity to lay his hands on his first movie camera, a Kiev-16U in early 1970-es. Not one to let the moment slip by, he hatched a plan to make his own film. Enlisting the help of friends, orchestrating scenes, and setting up a shot list, he diligently filmed a five-minute narrative. Anticipation filled the air as the film was sent off for development, only for disappointment to dash his hopes the next day—the film was blank.

‘How is this possible? We had actors, we had scenes!’ I remember arguing with the staff at the photo studio. ‘Could you detail how you loaded the film?’ they queried. ‘Well, I simply opened the box and loaded it,’ I clarified. ‘Did you undertake this task in a dark room?’ they further inquired. My youthful naiveté shining through, I retorted, ‘Why would I need a dark room? How could I possibly operate if I couldn’t see anything?’ (laughs)

Young Andrey Zvyagintsev

Enrolling in Novosibirsk’s theatre school at just 16, he refers to this period as a ‘short sprint,’ as his education spanned only 3.5 years before he could work in local theatre and have a predictable trajectory for future years. However, fate intervened when he saw the film Bobby Deerfield based on Erich Maria Remarque’s novel, featuring Al Pacino in the leading role.

‘It was 1982, and in the USSR the film was shown in black and white, and it was surprisingly great in this state. When I tried to revisit it 20 years later in colour, I couldn’t bear it. At that time, the film utterly captivated me. I realised I knew so little about acting; I couldn’t comprehend how Al Pacino could perform so mesmerizingly! Then, when ‘…And Justice for All’ came out, he became my lifelong idol.’

The film star Al Pacino altered Zvyagintsev’s worldview. Years later, when Zvyagintsev was nominated for a Golden Globe for his film ‘The Return,’ he had a chance to personally converse with his childhood hero, and this memory he cherishes deeply:

‘As the awards ceremony concluded, we all descended a staircase, and I found myself remarkably close to Al Pacino. I stared at his profile, contemplating what to say to him. Only when he vanished from my sight, I grasped that it was his talent that had revolutionised my life. After seeing his films, I knew I had to go study in Moscow. His talent was the catalyst that liberated me from my provincial artistic stagnation, lifting me up like Munchausen by the hair.’

Zvyagintsev (right) with producer Alexander Rodnyansky at the “Golden Globes” in 2017. Photo: AP

In 1986, Zvyagintsev indeed made the move to Moscow and enrolled in GITIS (Russian Institute of Theatre Arts) as an acting student. A year into the course, fate once again nudged him towards his directorial destiny when he watched Michelangelo Antonioni’s ‘L’Avventura’ (English: “The Adventure):

‘A friend, studying cinematography at VGIK, surreptitiously sneaked me into their auditorium. I knew nothing of Antonioni, but the film made my head spin; I was forever enamoured with cinema. As we left the screening, my friend invited me somewhere, but I declined: “I don’t want to go anywhere. Leave me be; let me sit and ponder.” Soon after, Moscow’s Cinema Museum opened, and I began frequenting it as if it were my job, just to watch films.’

On the set of the film “Loveless”. Photo: az-film.com

The Essence of a Director: Crafting Worlds from Ideas

After completing his education at GITIS, Zvyagintsev eschewed a career in theatre and even worked as a janitor until 1993. This modest occupation offered him staff housing, while he also took on minor roles in films and television series. Zvyagintsev’s directorial journey began in earnest with the making of commercials, but his status in the field was truly acknowledged with the release of his 2003 film ‘The Return.’ Despite all the accolades and international recognition, Zvyagintsev finds it difficult to encapsulate what it means to be a director.

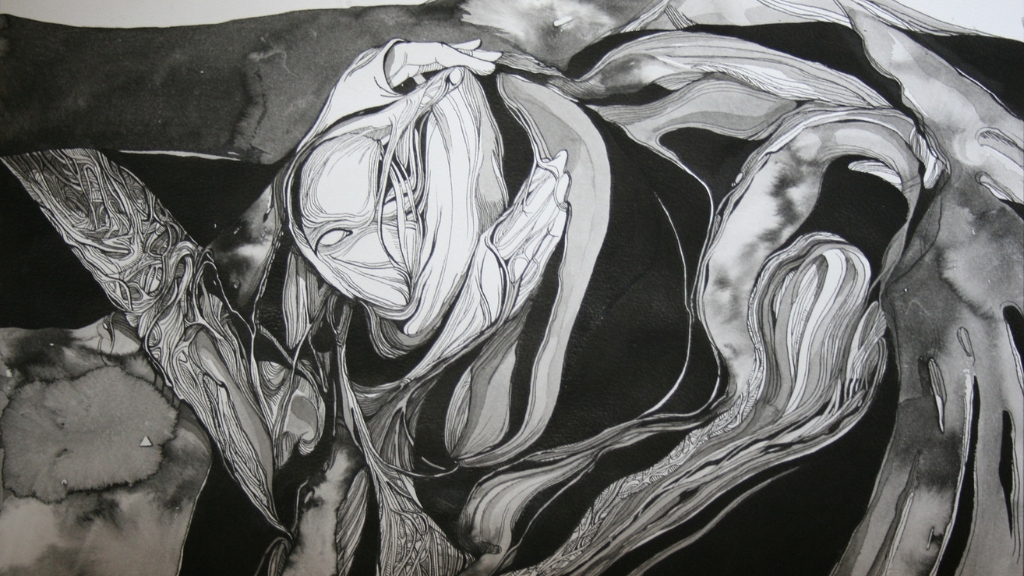

‘Perhaps it sounds grandiose, but the director is the film. You simply manifest what you’re compelled to create, what you dream of and see in your sleep, what you sketch on paper. Then, on set, thanks to the efforts of your comrades and meticulously selected actors, these abstract ideas take corporeal form. You give birth to a world. During the editing process, as you splice frames together, sparks of new meaning arise, and you witness the birth of a new world before your eyes.’

“On the Criticism that His Films are ‘Too Dark’

One of the most common criticisms levelled at Zvyagintsev’s films is that they are purportedly too bleak, focusing solely on grim aspects of life such as alcoholism, infidelity, dysfunctional parent-child relationships, and corruption. However, the director has a rejoinder to this:

‘You know, medicine is often bitter but brings healing. I was recently asked about the ending of the film “Loveless”: why I don’t provide clarity as to whether the boy is in the morgue or not. The truth is, I don’t have an answer; I don’t construct a closed narrative structure that leaves you with a comforting pill, a numbing injection that reconciles you with the world. If a film stays with you — if you leave the cinema, return home, and find that it still “turns” inside you — then it has achieved its purpose. The film poses questions to the audience; there are no soothing answers like “take comfort” or “to be human is to be noble.” Instead, such mantras are questioned. When encountering these images, you look at yourself and think, “What is happening to me?” This process is, I believe, extremely important.’

- On the set of the film “Exile”. Photo: Vladimir Mishukov / az-film.com

- Matvey Novikov on the set of the film “Loveless”. Photo: az-film.com

About Children in His Films

In many of Zvyagintsev’s films, the main characters are children, and young actors perform exceptionally well in their roles. As it turns out, this is the result of meticulous casting; the director personally oversees this process, not merely reviewing candidates’ photographs but meeting with each one in person.

“You’re simply looking for someone who can perform better than you can, someone who needs no explanation and will simply do it. In the case of ‘Loveless,’ the boy (played by Matvey Novikov — Editor’s note) was simply magical. We were shooting a scene where his character eavesdrops on his parents’ argument: Zhenya (the boy’s mother in the story, played by Maryana Spivak — Editor’s note) closes the door, and the child stands on the other side, and the audience sees him crying. But in reality, Matvey was crying, even without hearing any conversation in the kitchen: that day, we were shooting only his close-ups, and behind the door sat Boris (the boy’s father, played by Alexey Rozin — Editor’s note), silent. Matvey, alone with the camera, executed that scene — a truly talented individual!”

On the set of the film “Elena”. Photo: Vladimir Mishukov / az-film.com

About the Relationship Between Actors and the Director

Zvyagintsev has an equally caring approach towards adult actors. He confesses that he never allows himself to criticise them, as the fate of the film depends on the quality of the relationships formed.

“You can’t set out on a journey unless you’re in love with the actor. Even if you put on a smile, they’ll sense something amiss. A person can only overcome themselves, perform above and beyond, and exhibit talent under conditions of trust and love towards them. You fall in love with the actor as a person, and they can’t help but feel it; you proceed in harmony, and then no obstacles arise. If you want to ruin your film—start demeaning the actor.”

About Disappointments in People

Zvyagintsev’s tender relationship with his actors sometimes plays a cruel joke on him in new circumstances: like many nowadays, he has had to confront unpleasant revelations about people who were once close to him.

“When I hear how Kostya Lavronenko (who acted in the director’s films ‘The Return,’ ‘The Banishment’) suddenly turns up in different ranks, I find it hard to accept, but all I can do is close that chapter. The only question that arises in me is: did we not know each other at all? When you see that a person, from whom you expect no such turn, suddenly ends up on the other side, you realise one simple thing — you were skimming the surface. You imagined that this person thought the same as you about many things, but it turns out you never delved deeper.

On the set of the film “The Banishment”. Photo: Vladimir Mishukov / az-film.com

About Russian Cinema in the West Today

He is exploring opportunities overseas, acknowledging the particular challenges of doing so in the current climate. His concerns are less about the ‘cancellation’ of Russian art and more about the economic realities, issues that predate even the turmoil of the 2022 war.

When submitting Russian-language scripts along with projected budgets to prestigious Western film companies, Zvyagintsev and his team are often met with a straightforward proposition: “If you are willing to film in English, financing won’t be a hurdle.” This commercial stipulation arises from simple demographics—there are 300 million Russian speakers globally, as opposed to 3 billion who understand English. Market preferences further complicate matters; American audiences, for example, have a pronounced aversion to subtitled films, greatly preferring content in English, which naturally serves as a gateway to wider distribution and a broader audience.

Read more: Composer Alexander Scriabin: a journey from earthly melodies to celestial aspirations

Fortunately, Zvyagintsev has recently found producers willing to back a Russian-language venture. He strongly advocates for retaining the film’s linguistic integrity, believing that the nuances of relationships are most authentically captured in the characters’ native tongue. Zvyagintsev argues he couldn’t faithfully represent these intricacies if he were to, metaphorically speaking, ‘become an American or a Frenchman.’ The film’s concept, he adds, necessitates the use of the Russian language.

While there have been producers who’ve subtly suggested incorporating a renowned Western actor to play a pivotal Russian character as a strategy to unlock funding, Zvyagintsev dismisses such approaches. “Imagine Benedict Cumberbatch portraying a Russian oligarch,” he muses. “It would be nothing short of caricature—a flagrant misrepresentation. It’s simply not an honest approach to storytelling.

On international cinema and TV series

Zvyagintsev confesses that he doesn’t single out British cinema as a separate form of art; he has little affinity for the habit of categorising films by their country of origin. “Great films are made in every country; it all comes down to the artists involved. Take Roger Deakins for example, who worked on ‘The Shawshank Redemption,’ ‘The Reader,’ and ‘1917.’ He is originally from Britain, where he lived for many years and shot his early films. Now he resides in America. So what is he—British or American? To me, he’s simply an exceptional cinematographer; the rest is immaterial.”

Read more: Dostoevsky in London and his influence on the British classics

The rising tide of TV series hasn’t found favour with Zvyagintsev, and he attributes this to his directorial perspective. “If the production conditions are such that a director must churn out 12-15 minutes of finished material per day, then it’s a degradation of the profession. I couldn’t operate under those conditions; I am too meticulous and adhere to traditional standards, which involve generating one and a half to a maximum of three minutes of final material per day.

“I myself am not a diligent consumer of series. There are, undoubtedly, outstanding pieces of work, but they often lose their lustre by the third or fourth season. The television series industry is overvalued, creating an impression that the sheer volume of content produced doesn’t necessarily translate into quality. Among the exceptional ones, I would highlight ‘Fargo,’ ‘Mindhunter,’ and ‘Breaking Bad.'”

Andrey Zvyagintsev and Maryana Spivak/ Afisha.London

A Memory of London

Zvyagintsev has been to London on several occasions, and a visit to the British capital in 2005 nearly resulted in a short film.

“We sat down to have lunch in a small restaurant, but I was completely uninterested in eating. I became engrossed in observing an absolutely astonishing scene. We even surreptitiously captured footage of a young woman sitting at a neighbouring table. Imagine: over the span of 15 minutes, this girl gets progressively inebriated, engages in conversation with her companion, and falls head over heels in love with the man sitting opposite her. What a spectacle! Unfortunately, this can never be published due to privacy laws, and finding the woman now to ask for her permission is entirely unrealistic. So, I have a documentary that was filmed but will never be shown.”

Another memory tied to London for Zvyagintsev is the Russian Film Week festival. In 2017, his film “Loveless” won three awards there. Maryana Spivak, who played the leading role in the film, was recognised as the best actress and honoured with the ‘Golden Unicorn’ trophy. Afisha.London magazine spoke with the actress to find out what “lovelessness” means to her. You may read this text here (in Russian)

Discoveries After Coma

In 2021, it became public knowledge that Zvyagintsev was suffering from a severe form of COVID-19. He was hospitalised in a German clinic with 92% lung damage and was placed in a medically induced coma. After 40 days, the director was brought out of the comatose state, and a lengthy recovery process began. Zvyagintsev has since returned to work and to creative meetings with fans, and he is reevaluating the profound experience he underwent.

“After being in a coma for 40 days, I can definitively say—there’s no ‘corridor,’ no transitional phase between life and death. More importantly, I now feel entirely at ease with the concept of mortality, and I consider this a personal gain. Do you know why? The lights simply go out, and that’s it; you don’t get to have an opinion on the matter. Perhaps it sounds crude, but I’ve come to understand there’s nothing frightening about it. One moment they’re inducing me into a coma, and the next thing I know, 40 days later, I find myself in a different room with no recollection of what transpired. It’s like a direct cut in cinema—snap, and the credits roll.”

Afisha.London magazine expresses our gratitude to Mesmis.events and personally to Zurab Svanidze.

Cover photo: Anna Matveeva / az-film.com

Read more:

Composer Alexander Scriabin: a journey from earthly melodies to celestial aspirations

Bakst, Benois and Dobuzhinsky: How an Extensive Collection of Russian Art Ended Up in Oxford

SUBSCRIBE

Receive our digest once a week with quality Russian events and articles